|

during the mid-twentieth century, British art historian James Laver was among the first generation of “Fashion Theorists”: scholars who not only studied fashion history (itself a rather young discipline at the time) but also looked at dress within social, cultural, and psychological contexts and frameworks. Laver postulated that the motivation of dress fell into three basic categories: Utility (garments, accessories and grooming worn for a specific practical purpose); Hierarchy (garments, accessories and grooming worn to express our position and role in society); and Seduction (garments, accessories and grooming worn to beautify ourselves and attract others).

Given the theme of the 2012 conference, Sex, Money and Power in Jane Austen’s Fiction, the Utility principle need not concern us, and discussion of practical fashions such as pockets and pelerines may find their way into a different paper. Laver’s principles of Hierarchy and Seduction, however, certainly provide an excellent lens through which to view Regency fashion. Although Laver’s matrix may have its flaws, expressing socioeconomic status and displaying sexual attractiveness are both universal aspects of fashion throughout history. These themes are evident in examples dating back to the earliest organized societies, including Sumer and Egypt. The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries did not deviate from this paradigm, and indeed offered fashionable expressions of these concepts that serve as excellent models. Such analysis utilizing this matrix not only demonstrates the validity of Laver’s theories, it illuminates our understanding of the time in which Jane Austen lived and wrote by examining the most intimate form of material culture: dress.

Approaching the Regency years: Anglomania, revolution, revival

Many styles and trends converged and flourished during the Regency period. To understand the fashions of the time in the proper context, it is necessary to backtrack slightly into the eighteenth century. In 1775, the year of Jane Austen’s birth, very significant developments in fashion were underway. France had dominated high fashion for most of the eighteenth century, but developments at this time showed a decidedly English taste asserting itself. While the English style coterie of “The Macaronis” asserted a European sensibility on England with their ludicrous sartorial choices, the more important development went the other way: from England to Europe.

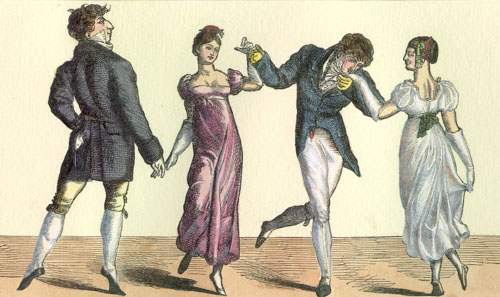

The simpler styles embraced by the British aristocracy at their country estates since earlier in the century had, by this time, made their way into town wear. From town wear in London, the styles soon spread to Paris and the rest of fashionable Europe, a look, taste, even lifestyle referred to as “Anglomania.” The look was markedly restrained, even casual by contrast to the more lavish styles of the mid-eighteenth century, and indicative of a strong shift in taste. Elements of riding attire, for both men and women, were typical, particularly the redingote: coats for riding for both sexes, for men astride and women side saddle, the name itself slang for “riding coat.” Women’s redingotes made the transition from true riding clothes into town wear and appear to have been very popular in Paris, where Queen Marie Antoinette was pictured in the style. The fashion plates depict women carrying riding crops in town, even when shown without an actual horse, giving the rather odd impression of the streets of Paris being populated by a significant number of dominatrixes. For men, the Anglomania look was often achieved with a simple riding style cutaway or tailcoat, worn with buckskin breeches, boots (frequently the two-toned “top boot” style), and a round hat, the precursor of the nineteenth-century top hat.

Anglomania was elite high fashion that had been born from the mystique of clothing used in the utility mode, transferring its purpose into hierarchy as the clothing styles migrated from country to town. The Anglomania styles were part of a greater phenomenon of celebrating country life that Inger Sigrun Brodey in Ruined by Design describes as “an urban society’s fanciful celebration of utopian rural simplicity” (197). The phenomenon of the Anglomania styles anticipates many twentieth- and twenty-first-century fashion phenomena, from sport influence in the 1920s, to Ralph Lauren’s country looks, even grunge, and today’s hoodies.

The Anglomania look promptly made its way across to Europe, where it was immortalized in numerous portraits, and in the clothes of the title character of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther. In addition to Werther’s simple ensemble, another male fashion staple from the Anglomania styles was the red coat for men, making the transition from the British military, to country wear, to town wear, and to European high fashion, where its use was undeniably dashing, even sexy.

In addition to the widespread adoption of the Anglomania styles, marked changes to fashion were encouraged by the tumultuous years of Revolutions: the American Revolution, the later French Revolution, and the ongoing Industrial Revolution. Sartorially the French Revolution made the most immediate impact, with changes particularly pronounced in France during the 1790s, and this decade offered rather acute as well as rapid and sudden transformations in styles. Although without a court to promote fashion between the Ancien Régime and the Empire, France, lead by the new intelligentsia of the Directoire, nonetheless had no problem creating and promoting outlandish styles, particularly extremes of Neoclassic ideas and attenuated and distorted proportions. Although elsewhere in Western Europe, in England, and in the young United States, the changes were a bit more gradual, nonetheless the fashion transformations during the 1790s were more notable and rapid than in any previous time in history. Also, with the slow but steady rise of industrialization came the slow but steady impact of capitalism on society, and clothing served as a marker of the upward mobility that was newly available to many members of society.

Adding to the stylistic complexity of the late eighteenth century, Neoclassicism was another undeniable catalyst of change, as the movement exerted a great affect on applied arts and clothing. Neoclassical styles and sensibilities were not new, as the examples of cultural influences of Greco-Roman civilization were apparent from the Italian Renaissance of the fifteenth century, and the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries both showed Neoclassical design influences. The eighteenth century’s Neoclassical movement had its most discernable fillip with the excitement created by the discovery of the ruins of Pompeii in 1748, and the taste grew steadily after. By the time of the reigns of George III and Louis XVI, the affect was significant and continued to grow more acute as the nineteenth century approached and dawned. The tastes of the Neoclassical movement eventually encouraged other historic revivals and ethnic inspirations.

Neoclassical ideals; Neoclassical exhibitionism

Neoclassical sensibilities created two notable looks that are decidedly linked to James Laver’s principle of Seduction. Interest in Greek and Roman style established extreme body consciousness, resulting in unusually sexually charged fashions. While other factors contributed to their development, the potent combination of Neoclassicism and Seduction defined their popularity and impact. These styles emerged during Austen’s youth and were of continued importance at the onset of the Regency years.

Women began wearing the robe en chemise, or “chemise dress” in the mid 1780s, a rather loosely fit and simply constructed garment that was typically made out of mousseline, light weight cotton associated with undergarments. The advent of the style is associated with Marie Antoinette, who is credited with introducing the fashion. Given its association with Marie, the dress was initially known as the chemise à la Reine, or the “chemise in the style of the Queen,” and the image was preserved by Elisabeth-Louise Vigée-Le Brun in her 1783 portrait of the Queen.1 The style initially met with some disapproval as its simplicity was considered by some to be inappropriate for the queen, and the sheer fabric associated with women’s undergarments gave it an added degree of scandal. Also, because of its simplicity, the influence of Anglomania can be assumed.

This soft, underwear-fabric dress continued (and flourished) after the queen’s execution, and in its new form became known as the robe en chemise. In this form, the robe en chemise took on the narrow silhouette and higher waistline of the Directoire period, enhancing the use of the thin mousseline fabric; it was now worn with reduced corsetry and petticoats, or without them altogether. With its lightweight fabric and its lack of undergarments, the robe en chemise was a natural vehicle to express both Neoclassicism and Seduction. Its gossamer fabrication and simple styling created an obvious, if superficial, comparison with the clothing worn by women in the Greco-Roman sculpture revered by the Neoclassical aesthetic. With reduced or absent foundation garments, a decidedly “classic” posture was achieved with a lower, freer bust.

The fact that what was once undergarment had become outerwear was already provocative and assured its sex appeal. But with reduced underwear—or no underwear—the sheer fabric clung to the buttocks, and nipples could be clearly seen through the garment, sometimes even enhanced by wetting the front of the dress, overtly and salaciously placing the garment into the category of Seduction (as if there were indeed any question). Some women with less desirable breasts took to wearing false breasts in order to achieve the requisite allure.

Although similar exposures of underclothes had been part of fashion in the Renaissance (and would again in the future) the effect was tantalizing. Although the greatest popularity of the robe en chemise was in France, the look certainly crossed the Channel, and it was widely appreciated as an object of lampoon by the cartoonists of the day. In addition to crossing the Channel it also crossed the Atlantic as the French fashions had a more direct line to the new United States of America.

The growing popularity of the chemise dress was also responsible for further promoting a taste for cotton. Cotton fabrics were already well established during the eighteenth century, encouraged by the slavery-based economy in European colonies in the Western Hemisphere, and new weaves and finishes for cotton were developed in European textile mills. Fancy cottons were often used instead of silk for fine gowns. The delicate, chiffon-like, fine muslin cotton mousseline was integral to achieving the Neo-classic mode for women and for fulfilling the full sex appeal of the robe en chemise. When in 1793, the Siege of Lyon drastically damaged the silk industry in France, the popularity of cotton mousseline grew exponentially, as necessity further encouraged the sexy aesthetic. In order to better recreate the feel of Greco-Roman style, the mousseline was used in whites and creams and soft pastels on the young and fashionable women who wore the chemise dress style.

Giving male sexuality equal time was the vogue for tight leather pants, typically in natural, cream-colored buckskin. The buckskin trousers came from the Anglomania wardrobe, originally favored by gentlemen for their practicality; they were also part of the ensemble worn by Werther in Goethe’s novel. Refining the pants to this tight leather version in a nearly nude color was quite likely inspired by the naked athletic legs in Greek and Roman sculpture; as such an artistic reference, the pants have been interpreted as the male version of the female chemise dress. The ideal fit of the pants was so tight that to achieve the high fashion look, men would wet the leather pants first, and then pull them on, allowing them to dry to the contours of their leg muscles, thus simulating the sculptural look. The look was a precursor of the sexually charged tight jeans of the late twentieth century. As with those jeans, it was fashionable for the fit of the buckskin pants to clearly expose the contours of the penis; such glimpses of male genitalia are evidenced in many portraits of the day.

The convention of the nude-color leather pants transferred quickly into military uniforms, where such a Neoclassical leg continued to be an ideal for some time; it is even the source of the continued use of white pants in some branches of the armed forces, a tradition that to this day carries some level of sex appeal. Although during the Regency years men sported a variety of pant shapes, tightly fitted cloth pantalons were a widespread fashionable option, often fabricated in knit for the man with worthy legs (or legs improved with padding), and the legacy of the Neoclassical tight leather form continued.

The status of high-status fashion icons

Not completely a new phenomenon at the time of Jane Austen, the celebrity fashion icon can be traced back at least to Akhenaton and Nefertiti in New Kingdom Egypt, or certainly to the style setting of cousins and fashion rivals Louis XIV and Charles II. But the role of celebrity fashion icons was increasingly developed by the late eighteenth century, and the role of Style Icon was inextricably linked to hierarchy.

Often different icons encouraged the same fashion on opposite sides of the Channel. Notably, Marie Antoinette, at the French court, and Georgiana Duchess of Devonshire, with her society appearances in London and Bath, were helpful in spreading Anglomania and its simpler dresses, pouter-pigeon front fichu, wide hat, and tousled hedgehog hair, along with other styles of the time. As Marie Antoinette promoted the chemise à la reine, it was also encouraged by Mary Robinson, poet, actress, and onetime mistress of the Prince of Wales; in England the dress was known instead as the “Perdita” in reference to Robinson’s acclaimed stage appearances as the character of that name in Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. Robinson’s association with Prince George certainly buoyed interest in her clothes, prefiguring the impact of royal favorites of the mid and late nineteenth century.

As for the later sexier version of the chemise dress, the robe en chemise, it became de rigeur for a well-dressed women in post Revolutionary France and had a number of stylish promoters amongst the intelligentsia of the Directoire elite, including Henriette Delacroix, Madame de Verninac, and the notable social figure Thérésa Cabarrus, Madame Tallien, who also promoted the markedly chic à la Titus hairstyle and has been credited with being one of the seminal style setters of the extreme Neoclassical fashions. The equally notable Jeanne-Françoise Julie Adélaïde Bernard Récamier was the object of great scrutiny by French society and became, to future generations, synonymous with the look.

Although the robe en chemise is commonly and rightfully linked to its French roots, the style had a distinct British exemplar in Emma, Lady Hamilton, as portrayed in the paintings of George Romney that immortalized her as his muse and his obsession. The same fashion image can be seen in later portraits of Emma by Elisabeth-Louise Vigée-Le Brun, who went so far as to depict Hamilton as a Bacchante dancing with tambourine at the eruption of Pompeii, depicting both her antique fashion sense and her bodacious sex appeal.2 Actress Dorothy Jordan, given both her stage appearances and her long-time importance as the mistress of Prince William, Duke of Clarence, in residence at Bushy House, was also an important style model.

The Empire years following the 1804 coronation of Napoleon naturally propelled Empress Joséphine de Beauharnais Bonaparte into position as the leading fashion exponent in France. (Joséphine had incidentally been an intimate of Thérése Tallien during the Directiore years.) Across the Channel, the ladies of the “Ton” at the elite social club at Almack’s Assembly Rooms were the undisputed arbiters of all things style. These included, among others, Emily Lamb, Lady Cowper and the sister of Prime Minister Lord Melbourne; Dorothea Leavin, wife of the Russian Ambassador; Countess Esterházy, wife of the Austrian Ambassador; and Sarah Villiers, Countess of Jersey and a mistress of the Prince of Wales (later the Prince Regent). These were the ladies who set the fashions of Regency Britain, and if they wore a style at Almack’s, a trend was assured some level of success. Although outside of the Ton, Lady Carolyn Lamb’s tumultuous affair with Lord Byron gave her the cachet of Romantic abandon; while she was not necessarily known for her clothes, her bizarre behavior, including ritually burning Byron in effigy, must have been appealing to a segment of poetic young ladies.

It is also at this time that the American style icon was born, primarily in the form of Dolly Todd Payne Madison, the wife of President James Madison (the term “first lady” was not yet in use.) Mrs. Madison’s French-influenced wardrobe set the fashion standard for the emergent upper-class intelligentsia of the new nation and created the archetype of President’s wife as fashion icon (to be followed by Francis Folsom Cleveland, Jacqueline Kennedy, and Nancy Reagan among others). The potent combination of expensive clothes worn by the consort of a head of state was perhaps the ultimate expression of fashion linked to power (and possibly continues to be), especially in an age when monarchies and courts were declining.

A new fashion system

A new aspect of fashion that worked hand in hand with these great fashion icons was the development of the modiste. The modiste—the precursor of the late nineteenth century couturier—represented the beginning of the elevation of the dressmaker and stylist to a status above servant or tradesperson, on a trajectory toward the level of celebrity. The role of the fashion icon combined with the development of the modiste linked fashion not merely to the wearer from royalty, court, or the upper class, but to a creative personality behind the style. These developments led to the designer’s imprimatur as a celebrity status symbol still in our culture today.

Marie Antoinette’s style was highly dependant on the acumen of her modiste Rose Bertin, who was likely responsible for a number of Antoinette’s fashion successes. During the French Revolution, Bertin wisely relocated to London, where prominent women of fashion appreciated her skills. As Marie Antoinette had Rose Bertin, fashion icon and Empress Josephine Bonaparte had her dressmaker, Louis Hippolite Leroy. Leroy’s career shows a further development in what would later be called the couturier, or even later, the fashion designer. Both Bertin and Leroy did what they did more than fifty years before the ascendance of Charles Frederick Worth and the supposed ground zero moment of French couture. These collaborations—Bertin and Antoinette, Leroy and Josephine—encouraged a cult of personality that anticipated not only the great style-setters of the nineteenth century but our own celebrity-obsessed age. The careers of Bertin and Leroy set in motion the celebrity fashion icon whose hierarchy in style is enhanced by her association primarily with one designer; collaborations such as the Empress Eugenie and Charles Frederick Worth, Wallis Simpson and Mainbocher, or Audrey Hepburn and Givenchy are indeed comparable.

In addition to all the above elements contributing to a celebrity status fashion system, we also see during this time a marked series of developments in what would become the fashion press, the vehicle through which celebrity style could be best disseminated. Fashion dolls had long been a method of sharing styles, but fashion plates became well developed, especially during the seventeenth century. This trend developed further in the eighteenth century. Published between 1778 and 1787, La galerie des modes et costume français, a folio of colored fashion plates that were primarily distributed as the entire folio and on a subscription basis, led the way to a new system of distribution of fashion plates. Following La galerie came the remarkable work of illustrator Nikolaus Wilhelm von Heideloff. Born in Germany in 1761, he lived in Paris until the outbreak of the revolution took him to London. Heideloff’s Gallery of Fashion was published monthly from 1794 to 1803 and was available on a subscription basis; it concentrated on specifically English styles. The Gallery of Fashion was followed by Ackermann’s Repository, published in Britain throughout the Regency years. These three collections of fashion plates represent an enormous step in the development of the fashion press, ultimately the quintessential creator of fashion icons and the quintessential method of distribution of information about the icons it creates, paving the way for the fashion magazines that would blossom during the fashion- and celebrity-obsessed years of the Second Empire. Additionally, England saw an important development in the ladies magazine, with La Belle Assemblée, or Bell’s Court and Fashionable Magazine, Addressed Particularly to Ladies, first published in 1806 and continuing throughout the Regency years. London fashion developed into an industry, and London dressmakers developed increasing name recognition.

Werther and Beau Brummell: Hierarchy by restraint, dress for success

In her 2009 article “Dressing for Success,” Clair Hughes argues that Werther’s Anglomania-style ensemble with its blue coat (and the subsequent copycat popularity the outfit had among young men across Europe) was the single most important moment in the shift into more sobriety in menswear during the nineteenth century. Werther’s ensemble both preceded and affected the edicts of Beau Brummell, and in its trajectory it eventually lead to the aesthetic of the well dressed male to the end of the twentieth century.

Brummell, the great Regency menswear arbiter and sometime intimate friend of Prince George, followed the paradigm of Anglomania and Werther, essentially making such restraint the mark of a fine gentleman and the official menswear look for the nineteenth century. Brummell and his circle propelled the style from anti-fashion into the ultimate of fashion. Brummell advocated a dark color story, inspired by military uniform colors and reflecting his time spent in Prince George’s regiment, allowing for the continuation of red coats, intended for country wear. His edicts also encouraged the growth of fine tailoring techniques, and the hierarchy expressed in the quality of construction equaled the restraint of the materials.

The outgrowth of Werther’s blue coat into the edicts of Brummell represents a sea change in fashion. For centuries prior to this time, hierarchy in men’s dress was typically expressed in lavishness of materials, specific dye colors, degree of ornate trimming, extremes of silhouette or detail. With this sea change, the status of a man was, by the Regency years, expressed by a sartorial subtlety that had not been seen before; the change continued to influence clothing through the twentieth century, perhaps reaching its zenith in the power suits of the 1980s and still affecting the way men dress today.

Sex and the Romantic imagination

Werther figures in our story again, and while his outfit was seminal to the development of power dressing, it was also the pinnacle of romance at the beginning of a time when exemplifying the Romantic sentiment was very attractive. The perverse romantic appeal of Werther’s clothes comes with the emotional power that he himself bestows upon them, writing “I want to be buried in these clothes. You touched them and they are sacred” (133).

Placing emotional response above the rational thought advocated by the Age of Reason, the Romantic Movement affected behavior, particularly in respect to love and mating; note that our vernacular modern usage of the word “romantic” is linked to coupling and sexuality. Extreme fashionable attributes for young women included a poetic frailty and sickliness. A young man of the day might have cut his own face to simulate a scar from a duel and likely did so less to impress his peers than to gain conquests among the ladies. Moodiness and melancholy became glorified and sexy.

Romantic spirit suited the new, fashionable, darker menswear color story well, and the dark and brooding emotional nature of the Romantic Movement has even been credited (if erroneously) for the ascendance of black as a menswear fashion color during the nineteenth century. Caspar David Friedrich’s monumental Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818) typifies such a spirit, as nature broods—simultaneously glorious and dangerous—at the feet of the man.3 The painting also exemplifies, if unintentionally, the color story and tailoring refinement advocated by Brummell. Like nature, the impeccably dressed gentleman is also broodingly seductive.

Anti-fashion fashion icon Lord Byron espoused styles that stood in contrast to Brummell’s fastidiousness, offering a sartorial alternative. With his noticeably unstarched and undone shirts, he set a standard for casual masculinity that in its disheveled style served as a prototype for later Bohemians; the undone shirt worn with loose or no cravat combined sex with anti-fashion as it both contradicted the edicts of high fashion and also implied undress, inviting the viewer to visualize the shirt opening further. The seductive nature of the an undone shirt symbolized the growing Romantic Movement as such shirt-styling appeared in portraits of Byron’s friend Percy Bysshe Shelley and of Ludwig van Beethoven, as well as other artistic and emotional young men of the day. Expressing a sartorial wildness in keeping with the Romantic Movement’s emphasis on emotional response, the undone “Byron” collar became a seductive staple of male fashion in the next few decades.

The hierarchy of historicism and exoticism, the romance of revival

Revivalism and Orientalism were hallmarks of nineteenth century style, and in fact the nineteenth century did not produce a genuinely original taste and style until its last quarter with the Aesthetic Movement and Art Nouveau. During the years of the Regency and the Napoleonic Wars, fashions took on the distinctly nineteenth-century form of overt revivalism, not simply of the ancient world, as evoked by the Neoclassical movement, but of the more recent past, the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries. The simpler women’s wear forms of the decade of the 1800s were embellished during the 1810s with any number of such historic details; although changes to fashion had slowed a bit following the establishment of the French Empire, the need to remain stylish and trendy was accomplished with bits and pieces of the past and of the globe sprinkled liberally into the fashion repertoire.

The elevated waistline remained parked below the breasts from the 1790s to about 1825. After the 1790s established a new silhouette rather quickly, the subsequent near stasis of the silhouette inspired volumes of new trims and details during the 1810s to allow the changes in fashion desired by the wealthy. Heavily trimmed skirts brought complex details back into fashion, more strongly asserted since the years of Madame de Pompadour. In the Regency years, complicated historic and orientalist elements provided lavish stylistic displays. As in Pompadour’s time, during the Regency such details were a vigorous vehicle for conspicuous consumption given their labor-intensive fabrications, and therefore a potent signifier of hierarchy for the upper classes who wore the styles. This kind of statement was particularly noticeable in profuse trimmings, especially on skirts where unrestrained details were common, along with cut edge details and edge trims.

Such elements served not only hierarchical purposes but seductive ones as well since often they were tied to strong Romantic sentiments, buoyed by art and literature. Fine art and Romantic fiction contributed to the revivalist vogue, strongly related to the poetic emotional life of an item of clothing or a style. The allure of the Middle Ages was clearly asserted by a variety of artists, including Friederich, Ingres, and Overbeck, as gothic ruins and knights and damsels filled paintings—a trend put forth in literature by Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe (1820). Complex womenswear details of dagging and scalloping were pronounced expressions of this theme.

Friederich Schiller’s play Mary Stuart (1800) may have contributed to the popularity of sixteenth-century details on clothing that served both seductive romantic functions (because of their association with the romanticized Scottish Queen) and hierarchical functions (because of the elaborateness of the details). Sixteenth-century elements were further encouraged by the setting of Scott’s epic poem The Lady of the Lake (1810). Such fashion features included the revival of slash and puff, which appeared on women’s wear after 1800 and developed through the years of the Regency and into the 1820s. Ruffs, a staple of sixteenth-century style, also returned to fashion and were primarily seen on women; however, male versions appeared in court dress, notably the somewhat monstrous coronation clothes seen in portraits of both Napoleon in 1804 and George IV in 1819. Of course both coronation ensembles indicate profuse use of other inspirational themes. Cavalier-style collars and cuffs were revived, as Scott’s The Bride of Lamermoor and A Legend of Montrose (both 1819) were set in the seventeenth century.

In addition to these historic influences, exotic Eastern influences also affected fashion, as the supremacy of European imperialism served as stylistic inspiration. Building on the chinoiserie of the eighteenth century, the spectacle of India became a primary form of orientalism, buoyed by the increased British colonial presence there. The Royal Pavilion at Brighton, built in Indian Islamic style resembling the Taj Mahal, was begun in 1787 and represents the apogee of such Indian style. The style was already strongly present in fashion during the 1790s, in feathered turbans and hammered wire embroidery, and it continued over a few decades. Cashmere shawls with paisley motifs, a style encouraged by Josephine Bonaparte and her circle, were high-status luxury items of women’s wardrobes. The popularity of the style led to domestic production of such shawls, famously in the Scottish town of Paisley that gave the Asian pattern its name. A portrait of Empress Josephine by Antoine-Jean Gros (1809) even shows her wearing a paisley shawl draped around her in the manner of a Greek Doric Chiton, thus melding the Indian and Neoclassical styles in one, a meld typical of simultaneous multiple influences on fashion.4

Styles for the upper classes also were influenced by southeastern Europe and the Ottoman Middle East, encouraged by the travels of designer Thomas Hope, the politics of Byron, and Napoleon’s Egyptian campaigns. A feathered turban, though Indian in appearance, was sometimes termed a “Mameluk” cap. A specific sleeve style, the “Mameluk” sleeve, was a very important high fashion detail during the 1810s. Similar sleeves were often described by other exotic names in fashion plates; the words used to express a variety of styles in fact indicate a wide range of ethnic influences being invoked, and in addition to à la turque, fashions were described even as à la russe and à la juive. European colonization in the South Pacific and the Malay Archipelago contributed fruits and flowers to lavish embroidery and lace patterns, such as the embroidery on men’s court dress coats.

A warmed-over leftover: The panier in Regency court dress

The panier, the basket-like, hooped under-support, had come into fashion during the early eighteenth century in the years of the French Regency. Other similar under-supports had been used in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as court dress styles. The panier reached its zenith as a fashion item during the middle years of the eighteenth century, and it continued until the Anglomania styles became popular. As the panier waned in popularity, the hip emphasis lingered in the form of pads. But the panier continued to be worn for court dress in many countries, and for special occasions. In France, its use naturally came to an end with the Revolution, but in Britain it continued through the 1790s as a feature of court dress and remained in court-dress usage throughout the Regency years. When court life was resumed in France during the Empire, the panier did not make a comeback; rather a new style, the court train, was adopted. The United States, with no court system, adopted the court train as eveningwear.

While the court train was used in Britain for full dress outside of court, paniers lingered at the British court, even when waning in usage at other European courts. The style became a particularly ghastly expression of hierarchy as it as combined with the fashionable raised waist, thus concentrating the fullness of the paniers at the ribcage. Expressions of hierarchy in dress throughout fashion history have often been appalling. This use of the panier was no exception. Fashion plates of these years shows women in British court dress clad in such paniers (sometimes even and decorated with Greek keys) and topped with ostrich feathers, showing an odd combination of elements used to express—rather hideously—the pinnacle of the Regency class system.

Our Miss Austen

Jane Austen’s letters reveal an interest in fashion documented with keen observations, such as her views on certain styles, her love of quality hosiery, and her fondness for hat trimmings. The descriptions of clothing in Austen’s work are not plentiful, but those that she does make are likely familiar to readers with intimate knowledge of her fiction. Though not abundant, the observations of clothes in her books are often witty and reflect many of the fashion traits discussed here. As the references to clothing in her novels are few, they are all the more essential to the message. Placing Austen’s characters in a vitally observed world around them, these discussions of fashion subtly emphasize Austen’s observations of the times. In Mansfield Park, Lady Bertram desires a shawl from the East Indies, and Miss Tilney in Northanger Abbey possesses a fondness for mousseline. In Pride and Prejudice, Bingley and Wickham are both described wearing blue coats (but it is certainly easy, at least for me, to visualize Mr. Darcy dressed in the brooding elegance of Werther combined with the fastidiousness of Brummell).

Clearly the fashions of the Regency years are exemplary of James Laver’s principles of seduction and hierarchy, with Neoclassical sex asserted alongside status-imbued Orientalist details, fine tailoring, developed fashion icons, and alluring romantic notions. I am certain that a woman of Austen’s intelligence and aptitude for human observations would have a very easy time wrapping her head around twentieth-century fashion theory, and that she would find Laver’s principles rather fascinating, even amusing. Surely the concepts of Laver’s principles, even without his terminology, were observations that Jane Austen made herself.

Understatement and wit underlie Austen’s writing; in keep with this subtlety, she appreciated the more refined styles of her day as opposed to the extremes of outrageous detail that the Regency years offered. A metaphoric similarity from Austen’s work can be discerned in Sense and Sensibility where Elinor’s practicality stands in calmer contrast to Marianne’s romantic flights of fancy and recklessness. When discussing manners, style, and dress in her novels and letters, Jane Austen often noted the elegance of a character, and the elegance of a style. Given her legacy of stylistic influence through many readings and film adaptations of her work, she created elegance as well.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Nancy Deihl of NYU; Nili Olay, Gene Gill, and Kerri Spennicchia of JASNA; and Susan Allen Ford, Editor of Persuasions/Persuasions On-Line.

Notes

1. This portrait of Marie Antoinette is in the collection of the prince Ludwig von Hessen und bei Rhein, Wolfsgarten Castle, Germany.

2. Vigée-Le Brun’s painting of Hamilton as a Bacchante is in the Museum of Liverpool.

3. Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog is in the Hamburger Kunsthalle in Hamburg.

4. This portrait of Josephine by Gros is in the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, Palais Massena, Nice.

Works Cited

Ashelford, Jane. The Art of Dress: Clothes Through History 1500-1914. New York: Abrams, 1996. Austen-Leigh, William, and Richard Arthur Austen-Leigh. Jane Austen: Her Life and Letters. Charleston, SC: BiblioLife, 2009. Barreto, Christine, and Martin Lancaster. Napoleon & the Empire of Fashion: 1795-1815. Milan: Skira, 2011. Blum, Stella. Ackermann’s Costume Plates: 1818-1828. New York: Dover, 1979. Boucher, Francois Leon Louis, and Yvonne Deslandres. 20,000 Years of Fashion. New York: Abrams, 1987. Byrde, Penelope. Jane Austen Fashion. Ludlow: Excellent P, 1999. Foster, Mandy, and Dannielle Perry. Regency Era Fashion Plates: 1810-1819. [U.S.]: Create Space, 2008. Ginsburg, Madeleine, Avril Hart, Valerie Mendes, and Natalie Rothstien. 400 Years of Fashion. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1993. Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. The Sorrows of Young Werther. 1774. Ed. and trans. Michael Hulse. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1989. Hart, Avril, and Susan North. Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Fashion in Detail. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2009. Hughes, Clair. “Dressing for Success.” Fashion in Fiction: Text and Clothing in Literature, Film and Television. Ed. Peter McNeil, Vicki Karaminas, and Catherine Cole. New York: Berg, 2009. 11-22. Johnston, Lucy. Nineteenth Century Fashion in Detail. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2009. Kelly, Ian. Beau Brummell: The Ultimate Man of Style. New York: Free Press, 2007. Le Bourhis, Katell. The Age of Napoleon: Costume from Revolution to Empire, 1789-1815. New York: Abrams/Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1990. Martin, Richard, and Harold Koda. Infra-Apparel. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art/Abrams, 1993. Morley, John. Regency Design: 1790-1840. New York: Abrams, 1993. Payne, Blanche. History Costume from the Ancient Egyptians to the Twentieth Century. New York: Harper, 1964. Ribeiro, Aileen. The Art of Dress: Fashion in England and France, 1750-1820. New Haven: Yale UP, 1995. _____. Ingres in Fashion: Representations of Dress and Appearance in Ingres’ Images of Women. New Haven: Yale UP, 1995. Shep, R. L. Federalist and Regency Costume: 1790-1819. Mendocino: Shep, 1998. Starobinski, Jean. Revolution in Fashion: European Clothing 1715-1815. New York: Abbeville, 1990. Watkins, Susan. Jane Austen’s Town and Country Style. New York: Rizzoli, 1990. Weber, Caroline. Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wore to the Revolution. New York: Picador, 2007.

|