|

as Elizabeth Bennet and her aunt and uncle Gardiner get the house tour of Pemberley, they take in the works of art on display, most notably the portraits of Mr. Wickham, Mr. Darcy, and Georgiana Darcy. This passage is one of the defining moments of Pride and Prejudice, a moment with complex meanings. Scholars and critics have correctly analyzed this scene in terms of Elizabeth’s shifting feelings: viewing the group of miniature portraits reveals something about Elizabeth’s “intimate” knowledge of both Darcy and Wickham, while her interaction with the large-scale portrait of Darcy in the gallery plays an important role in the gradual process of her deeper understanding of his character and social position.1 Furthermore, the visual nature of this passage has had an understandable appeal to anyone who adapts the novel to a visual medium. The scene has been represented by illustrators of the novel beginning with the Brock brothers at the end of the nineteenth century, and whatever else may be cut in the interests of timing or budget, most of the major film and television adaptations of Pride and Prejudice include this scene.2

This passage also reveals Jane Austen’s own knowledge of the appearance and function of portraiture. We know that Austen attended art exhibitions; she also would have known portraits and the artistic conventions informing them through her experiences of private collections. Additionally, she was familiar with the work of amateur artists like her sister Cassandra, who captured Jane’s own likeness. All of these experiences were doubtless brought to bear on the scene of art viewing at Pemberley. As is so often the case in her novels, Austen did not have to resort to too much description since she could rely on the fact that her contemporaries could visualize what she refers to. Based on their own knowledge of how portraits looked and functioned, Austen’s earliest readers would likely have understood aspects of the experience of the Pemberley portraits that may not register with modern readers unfamiliar with their art historical context. An exploration of portraiture in Austen’s time and place can draw attention to the implications of this scene in Pride and Prejudice.

This essay pauses alongside Elizabeth and the Gardiners to take a closer look at the Pemberley portraits as a way of delving further into both the realities and the higher ideals of the portrait genre in Austen’s time and place. First, an examination of how Austen and her contemporaries looked at and thought about portraits will reveal how those ideas influenced the viewing of the Pemberley portraits by Austen’s characters. A discussion of the ways in which portraits were displayed, particularly in grand houses, will enhance our understanding of how those installations created a framework for contemporary viewers’ perceptions of portraiture. Third, the placement of Austen’s visualizing into historical perspective can allow us to relate her visualization of these portraits to her own literary artistry.

Viewing portraiture in Austen’s time

Throughout the eighteenth century, portraiture was not without controversy. Art academies preached a hierarchy of artistic genres, a concept going back to the Renaissance. The grandest and most important genre was “history painting”: significant and morally instructive events from religious or classical history, involving numerous figures and a variety of emotional states, all ideally done on a grand scale. Lower down in the hierarchy was what we now call “genre painting”, scenes of everyday life, with landscape and still life at the bottom of the list.

The position of portraiture in this hierarchy was problematic. According to some theorists, it should be placed just below history painting, since it recorded the likenesses and status of prominent individuals. Other critics were not so sure: portraiture was thought by some to be too heavily indebted to likeness, not “ideal” enough to be in the same league as history painting. But eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century critics were beginning to recognize that, beyond recording a physical likeness, an important goal of portraiture was to capture a personality that could be visually “read.” Portrait painters were expected to combine direct observation of the specific qualities of their sitters with a more timeless sense of artistic idealization, a combination that can be discerned in Austen’s own writing.

As in so many areas—politics, society, technology, culture—the period of and around Austen’s lifetime saw a shift in attitudes about the portrait genre. Sébastien Allard puts it succinctly:

Between 1770 and 1830, portraiture as a genre was struggling to escape from the inferior position to which it had been condemned by academic hierarchies. Critics, theorists and the artists themselves all expressed very clearly the contradictions inherent in the genre: the tension between immutable beauty and ephemeral resemblance; between respect for social and sexual conventions and the expression of an individuality that could not be reduced to a type; and between the private dimensions of the genre and its public expression. (82)

Theory is one thing, practice is quite another. The reality was that, notwithstanding its “inferior position,” portraiture kept many an artist’s pot boiling, and this phenomenon was particularly true in Great Britain. Despite the best efforts of the Royal Academy (founded 1768), its first president, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and others to promote history painting, there was very little market for it. By contrast, portraiture flourished, thanks to two interrelated developments: high demand for portraits from a large and varied clientele (aristocrats, gentry, the newly prosperous, and the growing number of celebrities of various sorts) who wished to be artistically immortalized; and a line of outstanding artists (Reynolds himself, Gainsborough, Romney, Raeburn, and Lawrence, among others), who were able to meet that demand with images that were at least as important for their artistic qualities as for their verisimilitude.

The conflicts alluded to by Allard—between the ideal and the timeless on the one hand, and the lifelike and the specific on the other—inspired debates about the degree to which artists should idealize their sitters. It was “a truth universally acknowledged” that flattery was essential to portraiture, but the belief was that it was “the ‘general character,’ not the face, that must be flattered” (Shawe-Taylor 30). In other words, trying to make a sitter look prettier was problematic, but making sitters seem more powerful or more charming or in some way more intriguing was considered a desirable goal. Rather like Elizabeth Bennet trying “to unite civility and truth in a few short sentences” when praising Mr. Collins’s domestic happiness (216), a good portrait painter was expected to combine an accurate likeness with just enough idealization to please the sitter and make for a satisfying work of art.

The tension between the private and public aspects of portraiture to which Allard refers was mirrored at the Royal Academy by the tensions between a desire for discretion and a simultaneous desire for celebrity. Marcia Pointon states, “Until the end of the eighteenth century, the majority of portraits were recorded in the official exhibition catalogue [at Royal Academy exhibitions] in simple class terms (portrait of a nobleman . . . clergyman . . . lady, etc.)” (Pointon, “Portrait!” 95). This situation may remind us of Jane Austen’s ambivalent relationship with her own fame, publishing her novels anonymously but accepting a degree of celebrity once her identity was revealed.

Despite (or perhaps because of) these conflicts and ambiguities surrounding the genre, the status of portraiture rose during Austen’s lifetime, and it came to be thought of as an art form in which the British particularly excelled (Shawe-Taylor 21ff.). In a sense, the rise in the status of portraits coincides with the rising status of novels. In Northanger Abbey, Austen famously champions the best novels as “work[s] in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour are conveyed to the world in the best chosen language” (38). Similarly, from the second half of the eighteenth century, there was an increasing awareness that portraits could rise above mere likeness to capture the mind, soul, or personality of a sitter, as well as to be appreciated as works of art in their own right. Samuel Johnson praised Reynolds’s genius in “diffusing friendship, in reviving tenderness, in quickening the affections of the absent, and continuing the presence of the dead” (qtd. in Shawe-Taylor 28). William Combe wrote in 1777 that, while portraits were formerly thought of as “mere Trash and Lumber,” even people who did not know the sitter could now admire a portrait for its aesthetic qualities (qtd. in Shawe-Taylor 28). The greater respect accorded to both novels and portraits in Austen’s day is part of what John Brewer has called “a large transformation that occurred not just in works of art, but in ways of thinking about literature, viewing pictures and listening to music, in people’s sense of themselves as creative, tasteful, or polite, . . . and in the presence of new figures on the cultural scene such as the commercial impresario and the professional author” (Brewer x).

Austen seems to have been familiar with the questions and challenges surrounding portraiture, and this awareness is reflected in the way that she deals with portraiture in her novels. In an often-quoted letter to Cassandra from London of 18-20 April 1811, Austen writes: “Mary & I, after disposing of her Father & Mother, went to the Liverpool Museum, & the British Gallery, & I had some amusement at each, tho’ my preference for Men & Women, always inclines me to attend more to the company than the sight.” It would be misleading to read this passage as a straightforward admission on Austen’s part that, like her heroine Elizabeth Bennet, she “knew nothing of the art” of painting (PP 250).

In what is perhaps an even more often quoted letter to Cassandra, this one of 24 May 1813, we get clues that Austen understood the art of portraiture better than she had let on two years earlier. She describes her visits to several art exhibitions currently on view in London, particularly in terms of her quest (sometimes successful, sometimes not) to find images of her own characters:

Henry & I went to the Exhibition in Spring Gardens. It is not thought a good collection, but I was very well pleased—particularly (pray tell Fanny) with a small portrait of Mrs Bingley, excessively like her. I went in hopes of seeing one of her Sister, but there was no Mrs Darcy;—perhaps however, I may find her in the Great Exhibition which we shall go to, if we have time;—I have no chance of her in the collections of Sir Joshua Reynolds’s Paintings which is now shewing in Pall Mall, & which we are also to visit.—Mrs Bingley’s is exactly herself, size, shaped face, features & sweetness; there never was a greater likeness. She is dressed in a white gown, with green ornaments, which convinces me of what I had always supposed, that green was a favourite colour with her. I daresay Mrs D. will be in Yellow. . . . 3 [later that evening] We have been both to the Exhibition & Sir J. Reynolds’,—and I am disappointed, for there was nothing like Mrs D. at either.—I can only imagine that Mr D. prizes any Picture of her too much to like it should be exposed to the public eye.—I can imagine he wd have that sort [of] feeling—that mixture of Love, Pride & Delicacy.—Setting aside this disappointment, I had great amusement among the Pictures. . . .

It is tempting to interpret this letter as yet another example of Austen taking a greater interest in people than in art per se; but the light-hearted, ironic tone does not preclude a genuine understanding about the goals and functions of portraiture in her time. Austen knew that capturing personality through expression (“sweetness”) was at least as important as the capturing of likeness (“size, shaped face, features”), and that the choice of accessories (ribbons in favorite colors, for example) would undoubtedly have made a sitter more “recognizable” to those who knew her. She also seems to have understood the issues surrounding the public exhibition of portraits: a husband who is truly loving, proud in the best sense, and delicately sensitive to his own and his wife’s feelings, might choose not to “expose” her image at public exhibitions.

The letter of 24 May 1813 also displays Austen’s sophisticated awareness of the art world of her time. She can joke to her equally knowledgeable sister that she has “no hopes” of finding a portrait of the delightful, unpretentious Elizabeth Bennet Darcy in an exhibition of work by Reynolds. The Austen sisters apparently knew enough of Reynolds’s work to be able to pigeonhole much of it as a series of flamboyant portraits, often allegorized or mythologized, of the grandest members of the elite.4

Taking Likenesses

Austen clearly understood that mimesis, or naturalistic depiction, was essential to good portraiture: when Elinor Dashwood looks at the miniature shown to her by Lucy Steele, whatever “other doubts” she may have, “she could have none of its being Edward’s face,” and she returns it to Lucy, “acknowledging the likeness” (132). Certainly, Darcy’s portraits must be good likenesses, too. Elizabeth’s aunt and uncle recognize the “real” Darcy when they encounter him in the flesh a few minutes after having viewed the portrait (receiving confirmation from the “gardener’s expression of surprise on beholding his master”) (251).

It would be useful to know how the Pemberley portraits came to be painted. Tantalizing hints in the text allow some speculation. There were certain occasions for which a young man of the period would have had his portrait painted. One such occasion was upon his leaving public school; this practice was customary at Eton, where even artists of the stature of Sir Thomas Lawrence were called upon to paint young men at this juncture (Pointon, Portrayal 75ff.). A young man of Darcy’s status would almost certainly have had his portrait painted upon his coming of age.

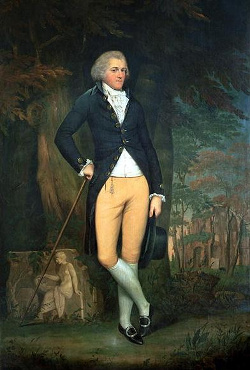

Another important rite of passage for young men of Darcy’s class was the post-university Grand Tour, an experience that was almost invariably celebrated with a portrait. The Rome-based painter Pompeo Batoni was only the most famous artist to depict these British “milordi,” often surrounded by classical ruins and sculptures, some of which they would have acquired as part of the tour. Jane Austen’s brother Edward (later Knight) went on the Grand Tour during the 1780s, and had his portrait painted (now at Chawton House Library) to prove it. Typically for such productions, it shows Edward at once as solid Country Gentleman, fashionable Man of the World, and sophisticated Man of Taste.

Based on the textual evidence, the most logical conclusion is that the portraits of Darcy would have been painted for his coming of age. We cannot rule out the possibility that the oil painting is a Grand Tour portrait, but this possibility is unlikely, partly because the Grand Tour was put on hold for much of Austen’s maturity due to the wars with France (this interpretation depends upon when one imagines the novel to be taking place), and partly because of Elizabeth’s thoughts on beholding it. The painting inspires her to muse on Darcy’s status as “lord of the manor” rather than “man of the world.” It is intriguing to entertain the possibility that the miniature portraits of Darcy and Wickham were taken when they left school,5 when they might still have been friends of a sort, but again that scenario is unlikely. School leave-taking portraits (at Eton, at least) were usually half-length oil paintings, not miniatures, and the sitters were typically in their teens.

It might be helpful to recreate the timeline. Based on the information supplied by Mrs. Reynolds, we know that the miniature of Darcy was done eight years before Elizabeth and the Gardiners see it. The portrait of him in the gallery was taken during the lifetime of his father (250), who died “‘about five years’” before the story takes place (200). Darcy is now twenty-eight, or at least he implies as much (369). The miniature of Miss Darcy was likely done at the same time as the miniature of her brother, since she is described as being “only eight years old” at the time (247), and she is now sixteen. This timeline leads to the conclusion that the oil painting of Darcy, and likely the miniature of him as well, were painted to celebrate his coming of age at twenty-one or thereabouts, and that his father commissioned the miniatures of Wickham and Georgiana Darcy at the same time. Most young women (even of the upper classes) would have been lucky to have had a portrait painted at the time of their marriage. It was certainly not unheard of for little girls to be painted in miniature, but it was by no means commonplace. That the elder Mr. Darcy did commission portraits of his son, godson, and eight-year-old daughter tells us a great deal about his affection towards them all and his desire to keep them near him (in virtual form) at all times.

Miniatures vs. oil paintings

If Austen’s only goal were to use a portrait to enable Elizabeth to see the “real” Darcy, why does she have Elizabeth and the Gardiners examine two portraits of him, of different types and media? I believe it is because Austen understood the significant differences between miniatures and larger scale portraits. She knew that each format had its own purposes, techniques and styles. The way that portraits were displayed and viewed at the time, however, created an ambiguous relationship between what could be called the private/public nature of miniature portraits and the public/private nature of large-scale portraits. Austen gives us clues that she also understood these ambiguities, and that they reflect Elizabeth’s shifting feelings, about Darcy in particular.

Both Janet Todd and Kristen Miller Zohn have cogently summarized the history of miniature portraits and their significance to the Austen family and in Jane Austen’s fiction. One firm link would be Austen’s comparison of her own work to the art of the miniaturist, quoted so often as to amount to a cliché—“the little bit (two Inches wide) of Ivory on which I work with so fine a Brush, as produces little effect after much labour” (16-17 December 1816). This comparison reveals her awareness of the materials and practices of miniature painting.

Miniature portraits had been painted and purchased in England since Tudor times. Courtiers commissioned and presented miniatures to one another as proof of friendship, loyalty, or romantic attachment. Originally kept carefully locked in cupboards and cabinets, miniature portraits began to be worn more openly from the 1560s (Salamon 96). Patricia Fumerton has analyzed the viewing of miniature portraits at the Elizabethan court in terms of the ostentatious display of intimacy that such portraits encourage. As Fumerton describes it, the miniature was the tiny end goal of a progress through increasingly smaller and presumably more private spaces—from presence chamber to privy chamber to bedchamber to locked cabinet to the portraits contained within it.

During the seventeenth century, miniatures began to be displayed more publicly, first in royal palaces, then in aristocratic houses, and they could be viewed with varying degrees of accessibility (Lloyd 14). As John Murdoch puts it, this was the first moment when miniatures moved from the “privacy of the closet to the semi-public world of the collector’s cabinet” (2). After 1768, the Royal Academy exhibitions made works of art in all media more accessible to a wider public, miniatures included (Pointon, “Surrounded”48).

From the 1760s a new vogue for wearing miniature portraits was set by Queen Charlotte, consort of George III; the Queen also displayed miniatures (under “shop glass”) in her dressing room at Buckingham House, the sort of private/public space frequently inhabited by royalty (Pointon, “Surrounded” 50). The commissioning and display of new miniatures and the collecting of historical ones was popularized by connoisseurs like Horace Walpole. Apparently, “only special visitors” would be shown his famous collection of historical and contemporary miniatures at Strawberry Hill, Walpole himself unlocking the room, alternatively called the Cabinet or Tribune (Lloyd 14-15). By this time, the wearing of miniatures was almost exclusively limited to women, although men also “owned and cherished” them (Pointon, “Surrounded” 59). Thus it is not surprising that the elder Mr. Darcy would have commissioned portraits of those he loved, that he would put them on display rather than wear them, and that they would be part of the house tour of Pemberley. Even if Mr. Darcy’s “‘favourite’” room (247) is not his dressing room, we can nevertheless assume it to be a fairly “private” space.

Austen certainly understood the conventions surrounding miniatures, and their employment in a kind of ostentatious display of intimacy. In Sense and Sensibility, the miniature of Edward Ferrars produced by Lucy Steele is taken by Elinor Dashwood to be incontrovertible proof of Edward and Lucy’s engagement (131-32). Lucy’s action of showing the miniature to Elinor is an act of intimacy twice over: according to the social conventions of the day, it would be nearly impossible for Lucy to possess such a portrait if there were not an intimate relationship between her and Edward; at the same time, showing the portrait to Elinor is part of Lucy’s campaign to make Elinor her confidante.

The miniature portraits at Pemberley differ from Lucy’s image of Edward in that they are on public display while retaining a character that is seemingly intimate. We can assume along with Elizabeth Bennet that the miniature of Wickham remains above the mantelpiece because the elder Mr. Darcy’s favorite room has been kept just as he left it (247). Although not quite as fetishistic about such matters as the Victorians would later be, there was already a sense that rooms should be kept as they were as part of the atmosphere of “remembrance” that would pervade such a room. One of the functions of portraits has always been to preserve the likenesses—the “presence”—of absent or departed loved ones. Mr. Darcy senior apparently used these miniature portraits in this way, and his son has preserved the entire room in turn as a remembrance of his father, even if it means that Wickham remains a presence at Pemberley, uncomfortably close to the Darcy siblings he has betrayed.

Austen must also have realized that miniatures and oil paintings differed stylistically. Miniaturists were still using techniques laid out by the great Elizabethan and Jacobean miniaturists, like Nicholas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver. Working in watercolor on ivory, miniaturists emphasized exquisite detail, linearity and clarity. By contrast, over the course of the eighteenth century, British painters had developed a style for oil painting that was more “painterly.” Although miniaturists had softened their style a bit by then, it was still an art form that emphasized light over shadow and linear clarity over painterly dash. By contrast, painters in oil employed a sumptuous, atmospheric style, emphasizing contrasts of light and shadow and the textures of the brushwork, a style first popularized in Britain by Sir Anthony Van Dyck in the seventeenth century. This latter style dominated the Royal Academy, and it was preferred by every major British portrait painter of Austen’s lifetime, from Reynolds to Lawrence. Outliers like William Blake and, later on, the Pre-Raphaelite painters (who snidely dubbed Reynolds “Sir Sloshua”) might prefer linearity and exacting detail. To the Royal Academy, however, the “colouristic bravura and vigorous handling of English painting” (Rosenthal 40) was favorably compared to what was felt to be the overworked preciosity of French Neoclassicism. Thus, Elizabeth can “see Darcy clearly” in the miniature, but the oil painting shows a more complex Darcy, and it inspires a more “impressionistic” response from her.

As noted above, Patricia Fumerton describes the Elizabethan process of moving from public spaces to private ones, culminating with the ostentatious display of intimacy in miniatures. The viewing of portraits at Pemberley works in the opposite fashion: Elizabeth and the Gardiners first encounter the absent Darcy in miniature form, and only then move on to the picture gallery to view the “public” portrait of him. It is tempting to speculate that Austen deliberately uses the progression of Elizabeth’s reactions to the portraits of Darcy to mirror the move beyond mere likeness that characterized portraiture itself at the time. Elizabeth is first asked to acknowledge the accuracy of the miniatures, then seeks Darcy’s likeness in the gallery, finally achieving a deeper understanding of his status as powerful and benevolent landlord as she views the large portrait.

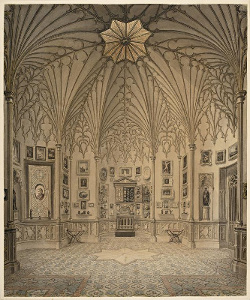

The Darcy family gallery

Austen’s narrator does not provide a detailed description of the setting of the larger portrait, but we do know that it is part of a gallery of ancestral portraits. The placement of long galleries in grand English houses went back at least to the sixteenth century. Originally designed to provide space for exercise during the winter months, galleries were discovered to be effective for the display of dynastic portraits. This arrangement would provide something for people to look at and talk about as they walked as well as an opportunity to stroll through a family’s history. Oliver Millar, however, notes that “[by] the end of the eighteenth century many of the old long galleries and their contents were in a neglected state” (32). That the gallery at Pemberley provides a climactic high point for a tour of the house speaks volumes about Darcy’s commitment to his family gallery, which he would no more neglect than he would his family library.

Many families who could afford more than one residence might, earlier in the eighteenth century, have used one of them (either the house in town or the grander and “newer” country house) for the display of “artier” pictures (your Rubenses and Rembrandts, Carraccis and Canalettos), and an older country house for the ancestral portraits. This situation began to change in the second half of the eighteenth century, when some of the “fine art” might be moved to a family’s country house(s) (Haskell 51). The reasons for this movement of works of art from town houses to country houses are not always clear (Brewer 220). One possible explanation is that, in a century that fetishized “taste,” collections of the most prized of art works could be as important as ancestral portraits in establishing the social standing of a family.

It is possible that Mr. Darcy displays some of his art collection at his house in town (and we know he has one, because Mrs. Bennet says as much shortly before going “distracted”) (378). On the other hand, we know of no other Darcy country residence besides Pemberley; thus there might be no distinction between the setting for the Darcy family’s “art” collections and their ancestral portraits. It seems that the gallery at Pemberley contains “many good paintings” (which, as mentioned above, Elizabeth, knowing “nothing of the art,” fails to appreciate) as well as family portraits (250).

The ancestral portrait gallery was clearly an ostentatious display of lineage. There would be little chance of anyone outside the family (and, by extension, their social class) making it into such a distinguished lineup. Even a reader of Pride and Prejudice unfamiliar with the nuances of Georgian class structures will catch Caroline Bingley’s snide tone when she teases Darcy about the possibility of placing the portraits of the lowly country attorney Mr. Philips and his wife in close proximity to Darcy’s great uncle the judge (52-53). Miss Bingley’s sarcasm expresses concerns voiced at the time (on the part of snobs, at least), based on their experience of public exhibitions; as Marcia Pointon notes, “portrait painters could be hired by aristocrats and merchants alike, and images of these men and their families mingled promiscuously on the walls of the [Royal] Academy” (“Portrait!” 93).

A family portrait gallery was intended to impress, even overwhelm, outsiders who would not recognize most of the people represented in the paintings. This type of display, in which ancestral portraits are viewable by a select public who may not know exactly who or what they are viewing, is what I meant by the ambiguous public/private nature of full-scale portraits. One can imagine visitors being made to feel even more like interlopers as previous owners of the house (literally and figuratively) look down upon them. As noted above, even at Royal Academy exhibitions, sitters in portraits might not be specifically named. This lack of identification might be a source of self-satisfied amusement for those in the “in crowd” who could recognize the sitters, but it might be intimidating to those who could not, unless they felt themselves qualified enough to appreciate the paintings on aesthetic grounds alone. Even Elizabeth Bennet, not easily intimidated, has been uncomfortable about visiting Pemberley, and her response to the parade of unfamiliar faces in the Pemberley gallery is ambivalent: “In the gallery there were many family portraits, but they could have little to fix the attention of a stranger” (250). It is odd that Elizabeth Bennet, who so loves to analyze other people’s characters, does not seem particularly interested in the personalities on display. Her lack of confidence in judging artistic quality, her decreased confidence in judging people (a feeling that she has experienced since reading Darcy’s letter), and her increasing focus on discovering the “true” Darcy may all be contributing factors to this indifference.

Even at this point, Elizabeth still seems overly concerned with the concept of likeness―she “walk[s] on in quest of the only face whose features would be known to her”—but her quest leads to the climactic moment of the portrait viewing scene.

At last it arrested her—and she beheld a striking resemblance of Mr. Darcy, with such a smile over the face, as she remembered to have sometimes seen, when he looked at her. She stood several minutes before the picture in earnest contemplation, and returned to it again before they quitted the gallery. Mrs. Reynolds informed them, that it had been taken in his father’s life time. (250)

Again, Austen’s narrator does not provide much in the way of description for this portrait; but I believe that Austen uses a few verbal clues to draw upon her (contemporary) readers’ expectations.

To begin with, we can probably assume that the large portrait of Darcy shows him standing in a landscape. This format was a conventional way of representing a sitter as a landowner, the master of his surroundings. Middle class or professional men might be shown three-quarter-length and seated at a desk, but landed gentlemen were usually not. Elizabeth’s reaction to the portrait reinforces this hypothesis. Where the miniatures confirm for Mrs. Reynolds and the Gardiners Elizabeth’s “intimate” knowledge of Darcy, the larger portrait gives Elizabeth an opportunity to muse upon his public role: “As a brother, a landlord, a master, she considered how many people’s happiness were in his guardianship!—How much of pleasure or pain it was in his power to bestow!—How much of good or evil must be done by him!” (250-51). Elizabeth has been increasingly impressed by the extent of Darcy’s grandeur, benevolence and good taste throughout the visit, but her feelings reach a peak as she views the portrait.

The other thing that Austen could expect her readers to assume about this larger portrait is that it is in the dashing, painterly style that (as noted above) had become the accepted style in Britain for portraits in oils. The boldness of this style was thought to be particularly suitable for male sitters; an application of paint “which is neither finicky, hesitant nor watery” (Shawe-Taylor 91) would convey a “manly” forthrightness of character that would be appropriate to Mr. Darcy. Again, this assumption is supported by Elizabeth’s reaction to the painting; her “earnest contemplation” of the portrait is part of her ongoing attempt to decipher his character. A portrait—or so it was felt at the time—was an attempt to capture as many facets of an individual as possible within a single image, and this particular portrait inspires Elizabeth to meditate upon Darcy’s integrity and altruism even as it celebrates his status as landowner. Contemplating Darcy’s likeness in way that she has never looked at the “real” man, Elizabeth realizes that Darcy’s personality and status are interconnected.

The idea that a portrait is a substitute for an absent person, one that is almost as animated as the living person, is a concept that went back at least to the Italian Renaissance. A famous instance concerned a portrait of the courtier, diplomat and writer Baldassare Castiglione (c. 1514-15, Musée du Louvre, Paris) by Raphael. Castiglione writes a poem in which he imagines his wife and son, whom he has left behind, “fondly communing with Raphael’s portrait in his absence, consoling themselves with his likeness and imagining it to be on the point of speech” (Jones and Penny 162). Similarly, Darcy’s portrait is not merely a stand-in for the “real man,” a way of describing Darcy as an absent presence, although it is those things, too; the portrait enables Elizabeth to engage with Darcy in a more emotionally open way than she has been able or willing to do before.

There is one thing we do know for certain about Darcy’s portrait: he is smiling. Being portrayed with a smile is not a universal trait; in many cultures and time periods it is more important to convey dignity rather than friendliness. Again, this situation had changed by Austen’s time: smiling for one’s portrait was becoming more customary as affability and amiability were becoming desirable social traits. Artists were expected to supply witty, engaging conversation, in order both to avoid tedium during sittings and to “animate the countenance” (Shawe-Taylor 16). Friends and family were often invited to portrait sittings to keep the sitter entertained. Thus, we can add another potential layer of absent presences to the portrait. Darcy may have been smiling at his father or sister, who might have been present as the portrait was painted. Elizabeth gazes at the image of Darcy and remembers the smiles he has directed at her.

On the other hand, Darcy’s painted smile is not always an indication of his character, even when he is in his domestic element; Charles J. McCann reminds us of Bingley’s statement that he “‘do[es] not know a more awful object than Darcy, on particular occasions, and in particular places; at his own house especially, and of a Sunday evening when he has nothing to do’” (McCann 72; PP 50-51). Bingley does not tell us whether he means Darcy’s house in town or his beloved country house, where we might expect him to be in his element; but Darcy can be unpleasant even at Pemberley, as when his response to Miss Bingley’s savaging of the absent Elizabeth inflicts pain (not entirely undeserved, it must be said) to “no one” but Miss Bingley herself (271). Once again, we are reminded of Darcy’s complex personality, and how one portrait alone does not suffice to capture all the facets of it.

When dancing with Darcy at Netherfield, Elizabeth tells him that she has been attempting the “‘illustration of [his] character,’” but does “‘not get on at all’” (93). After that moment, increasing evidence enables Elizabeth to construct a better “likeness” of him: the “sort of intimacy with his ways” (207) that she develops while staying in Kent, his letter after the disastrous proposal at Hunsford, the testimony of that portraitist manqué, Mrs. Reynolds. The multiple painted portraits of Darcy at Pemberley, the large portrait in particular, are also important factors that enable Elizabeth to add to the “portrait” of him that she has been working on for months. Clearly, Austen was aware of the limitations of portraiture, but she was also sensitive to its possibilities for conveying the complexities of character. Susan Morgan, rightly taking to task those who see Austen only in terms of dogged fidelity to “realism,” says that “Austen is no portrait artist, but a luminous maker of the world she sings” (4). I would amend this statement just slightly. We can all celebrate Austen as enlightened bard, but Austen is indeed a great portrait artist, if portraiture is given its due for depth, complexity, and sophistication as an art form. All of these potentialities of portraiture were acknowledged and celebrated in Austen’s time, as she herself knew, and as she strove to approximate in her own marvelous portraits.6

Notes

1. In recent issues of Persuasions and Persuasions Online alone, Kazuko Hisamori has discussed the truth-telling nature of portraits and their relationship to the Gothic, and Teri Campbell has analyzed faces in Pride and Prejudice based on contemporary ideas of beauty.

2. The adaptations of 1980 (BBC), 1995 (BBC/A&E) and 2005 (Focus Features) all include this scene.

3. Martha Rainbolt first identified this portrait as a painting of Harriet Quentin [“Mrs. Q.”] by Huet-Villiers (present whereabouts unknown), and this identification has become generally accepted in the Austen literature.

4. Janine Barchas, drawing on the work of Vivien Jones, notes that it is Mrs. Reynolds, the housekeeper at Pemberley, who “sketches” the character portraits of Darcy and Wickham (146). Perhaps the reference is ironic: as her namesake often did, Mrs. Reynolds gives her employer a “‘most flaming character’” (258).

5. Although it can be assumed that Darcy attended one of the prestigious public schools, we cannot be sure whether Wickham did the same. All Darcy says is that his father “‘supported [Wickham] at school, and afterwards at Cambridge’” (200).

6. I am grateful to William Phillips, Susan Allen Ford, and the anonymous reader of this essay for their help.

Works Cited

Allard, Sébastien. “The Status Portrait.” Citizens and Kings: Portraits in the Age of Revolution 1760-1830. Ed. Norman Rosenthal. London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2007. Austen, Jane. The Novels of Jane Austen. Ed. R.W. Chapman. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1933-69. Barchas, Janine. “Artistic Names in Austen’s Fiction: Cameo Appearances by Prominent Painters.” Persuasions 31 (2009): 145-62. Brewer, John. The Pleasures of the Imagination: English Culture in the Eighteenth Century. New York: Farrar, 1997. Campbell, Teri. “‘Not Handsome Enough’: Faces, Pictures, and Language in Pride and Prejudice.” Persuasions 34 (2012): 207-21. Fumerton, Patricia. Cultural Aesthetics: Renaissance Literature and the Practice of Social Ornament. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1991. Haskell, Francis. “The British as Collectors.” The Treasure Houses of Britain: Five Hundred Years of Private Patronage and Art Collecting. Ed. Gervase Jackson-Stops. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art; New Haven: Yale UP, 1985. 50-59. Hisamori, Kazuko. “Facing a Portrait of the ‘Lover’: Frankenstein’s Monster and the Heroines of Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice.” Persuasions On-Line 32.1 (Win. 2011). Jones, Roger, and Penny, Nicholas. Raphael. New Haven: Yale UP, 1983. Le Faye, Deirdre, ed. Jane Austen’s Letters. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. Lloyd, Stephen, and Kim Sloan. The Intimate Portrait: Drawings, Miniatures and Pastels from Ramsay to Lawrence. London: British Museum; Edinburgh: National Gallery of Scotland, 2008. McCann, Charles J. “Setting and Character in Pride and Prejudice.” Nineteenth-Century Fiction 19 (June 1963): 65-75. Millar, Oliver. “Portraiture and the Country House.” The Treasure Houses of Britain: Five Hundred Years of Private Patronage and Art Collecting. Ed. Gervase Jackson-Stops. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art; New Haven: Yale UP, 1985. 28-39. Morgan, Susan. In the Meantime: Character and Perception in Jane Austen’s Fiction. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1980. Murdoch, John. Seventeenth-Century English Miniatures in the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. London: Stationery Office, 1998. Pointon, Marcia R. Hanging the Head: Portraiture and Social Formation in Eighteen-Century England. New Haven: Yale UP, 1993. _____. “Portrait! Portrait!! Portrait!!!” Art on the Line: The Royal Academy Exhibitions at Somerset House, 1780-1836. Ed. David H. Solkin. New Haven: Yale UP, 2001. _____. Portrayal and the Search for Identity. London: Reaktion, 2013. _____. “‘Surrounded with Brilliants’: Miniature Portraits in Eighteenth-Century England.” Art Bulletin 83 (Mar. 2001): 48-70. Salamon, Linda Bradley. Commentary and Apparatus. Nicholas Hilliard’s Art of Limning. By Nicholas Hilliard. Transcription Arthur F. Kinney. Boston: Northeastern UP, 1983. Shawe-Taylor, Desmond. The Georgians: Eighteenth-Century Portraiture and Society. London: Barrie, 1990. Rainbolt, Martha. “The Likeness of Austen’s Jane Bennet: Huet-Villiers’ ‘Portrait of Mrs. Q.’” English Language Notes 26.2 (Dec. 1988): 35-43. Rosenthal, Michael. “Constable and Englishness.” The British Art Journal 7.3 (Win. 2006-07): 40-45. Todd, Janet. “Ivory Miniatures and the Art of Jane Austen.” British Women’s Writing in the Long Eighteenth Century. Ed. Jennie Batchelor and Cora Kaplan. New York: Palgrave, 2005. 76-87. Zohn, Kristen Miller. “Portraits of Imperfect Affection: Portrait Miniatures and Hairwork in Sense and Sensibility.” Persuasions On-Line 32.1 (Win. 2011).

|