|

in 1737 Elizabeth Knight of Chawton, having outlived two wealthy husbands, died. Any land she had inherited from them as their widow for the duration of her lifetime passed back to her husbands’ families. In the absence of any children or other direct descendants, her lawyers had ensured that her Chawton and Winchester estates would be securely protected in the future, rather than being subsumed into her late husbands’ estates, and that the name of Knight would endure. Seventy years later the ramifications of the strict settlement she created began to reverberate around Chawton and continued to bring stress and financial worries to a family whose younger daughter had begun her novel “First Impressions,” drawing upon the legal wrangles in which her brother would become involved. To understand the very personal subtext in Pride and Prejudice and a source of inspiration for Jane Austen’s writings, a closer look at the machinations surrounding Edward’s case is required, starting with the death of Elizabeth Knight and the various legal actions brought by the Hinton and Baverstock families in their repeated attempts to claim what they thought was rightly theirs.

Two questions need exploring. First, to what extent did Jane, as a young, unmarried woman, know of the history of estate ownership and the need to resort to legal processes when buying, selling, or exchanging land or when an heir reached twenty-one? Second, to what extent was she privy to the intense family discussions and the legal advice received by Edward from his lawyers? The only sources to answer these questions are various legal documents relating to the Chawton estate and Jane Austen’s letters and novels written during the period of Edward’s legal battle against the Hintons and the Baverstocks.

There were two ways to pass on a freehold estate through inheritance. The first method was by “fee simple,” where there were no limitations on what happened subsequently to the land. As no conditions were attached to the inheritance, the beneficiary could sell, develop, or gamble it away, or bequeath it to whomsoever he wanted. The second method was by “fee tail,” where the estate was entailed and hence could only descend linearly to the grantee’s heir and their heirs. The inheritor could not break up the property in his lifetime or choose the person to whom he bequeathed it. He therefore had a life interest only. Entails could only be barred by an Act of Parliament. Although a successful business women, Elizabeth Knight, following the norms of the age and the advice of her lawyers, restricted the succession to tail male rather than tail general, which recognized female succession. In Pride and Prejudice, Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s female relatives did not suffer the fate of the Bennet daughters as Rosings was not entailed away from the female line. Tail general was problematic. Daughters inherited in common—that is, the estate was shared among them. In Emma, Hartfield is shared equally between Emma and Isabella. On marriage, unless barred by the marriage settlement, the husband became the legal owner of his wife’s assets, so there was also a need to deter fortune hunters like Wickham. A strict entail tail male prevented distant relatives like cousins from inheriting. As Elizabeth Knight had no children or near relatives, she would have been aware that male heirs were not assured and that therefore provision must be made in such an event.

An entailed estate determined who was to inherit initially, but there was no insurance that the entail would be not broken or barred by a legal process called Common Recovery. This process was a collusive lawsuit whereby land was transferred without resorting to conveyance. As a result, the entail was broken and the estate transferred to trustees prior to the setting up of a new settlement. A legal device using settlement and remainders ensured that an estate was tied up. In a simple settlement the estate was granted “to A and his heirs, to the use of A for his life with the remainder to the heirs of his body.” At the same time the estates were conveyed to trustees during the life of the son in order to protect the contingent remainders (Habbakuk, “English Landownership”). A vested remainder in an estate passes to a named or defined person (e.g. heir of the body). A contingent remainder is an interest that passes to a person only under certain circumstances—for example, failure of an heir and his heirs to produce an heir. People with such an interest were known as “remainder men.”

Elizabeth Knight’s very detailed will, written by lawyers paid by the word, stated:

To and for the life of the aforesaid Thomas May of Godmersham for and during the term of his natural life without impeachment of waste and from and after the determination of that Estate by forfeiture or other ways. To the use of said William Guidott, John Baker and Edward Mumford and their Heirs during the life of the said Thomas May. In trust to preserve the contingent remainders . . . the said Thomas May and his assignees to receive the Rents and profitts thereof to his and their own use during his life and after the decease of the said Thomas May. To the use and behoofe of the ffirst Son and all and every other the Son and Sons of the Body of the said Thomas May lawfully begotten or to be begotten and of the heirs male of his and their Body and Bodies lawfully issuing severally and successively one after another as they and every of them shall be in priority of Birth and Seniority of age the Elder of such Sons . . . always to be preferred before the younger of such Sons. (TNA: PROB 11/688/170)1

In the event of this line failing, the estates would pass, with the same stipulations as for Thomas May, to William Lloyd, attorney of Newbury and his male heirs, and, finally, to Rev. John Hinton of Chawton and his male heirs. Any inheritor of Chawton was required to change his name to Knight as Elizabeth Knight (formerly Martin) and her brothers had done.2 No other surnames could be used or attached to it, and all children were also required to take the name Knight.3 Failure to do so meant that they would forfeit the lands, which would then pass to the next claimant. This stipulation dates back to the will of Sir Richard Knight of Chawton, who died in 1679 without children (HRO: 39M89/E/T12). He left his property to Richard Martin, Elizabeth’s brother, with Chawton House and its farm being reserved for his widow for her lifetime. There was no tail male restriction, but if Richard did not change his surname to Knight, the estate would pass to Sir Richard’s “brother-in-law,” Edward Husbands.4 The importance of the Knight name was so great that both Elizabeth’s husbands, William Woodward and Bulstrode Peachey, either changed their name to Knight or appended Knight to their names.

Elizabeth added a residency clause: the inheritor was required to live with his family in Chawton for at least six months of the year. In addition, all her goods and furniture were to be kept in the house as heirlooms and could not be to be removed or sold. Furthermore the house and gardens had to be maintained in a “very decent and handsome manner.”5 Elizabeth’s trustees were William Guidott of Lincoln’s Inn, Rev. John Baker (kinsman and Rector of Chawton 1718-1742), and Edward Munford (her steward). Trustees were not necessarily solicitors but could be family friends. On their death, their role would pass to their sons or other relatives.

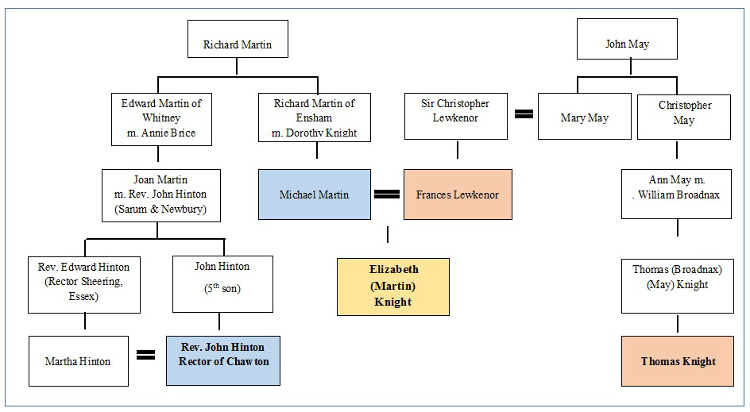

Table 1 illustrates how Thomas May and Rev. John Hinton were related to Elizabeth Knight through the Martin, Lewkenor, and May families. The Hintons were related through Elizabeth’s father, Michael Martin. His cousin Joan had married Rev. John Hinton (Rector of Sarum and Newbury). Unusually, the preferred line in Elizabeth’s bequest passed through her maternal grandfather, Sir Christopher Lewkenor, then to the Mays, and through Ann May’s marriage to William Broadnax and their son, Thomas.

It should be noted that Elizabeth Knight’s Winchester estate of Abbots Barton was inherited from the Lewkenor family. William Lloyd was the son of Rev. William (deceased) and Anne Lloyd of Chawton.6 Elizabeth Knight’s relation to the Lloyd family is not known—Anne Lloyd may have been the relative. Under the system of primogeniture, it was the Hinton family who were heirs-at-law, but the eldest son, Edward, was not favored. When Elizabeth’s will was written, he was sixty-six and had only one daughter. Elizabeth wanted to make sure that her estates stayed intact and that the good name of Knight was not compromised. Thomas May was a successful landowner with two estates, Godmersham in Kent and Rawmere in Sussex. Elizabeth’s will suggests that there was some doubt whether the young John Hinton, grandson of Joan Martin, was, when she wrote her will, mature enough for the challenge.7

Thomas May of Godmersham was born a Broadnax but changed his name to May in 1727 when he inherited property in Rawmere, Sussex, from his uncle, Sir Thomas May. The condition of Elizabeth’s will saw him, for a second time, asking Parliament’s permission to change his name, this time from May to Knight. The owner of Godmersham now had extensive estates in Sussex, Surrey, and Hampshire. Thomas was a “tenant for life”; no decision could be made that would impinge on the inheritance of his heir (the tail). He was only entitled to the rental and investment income and could not sell the land. Thomas and his wife, Jane Monk, had one son, Thomas, who was born in 1735, thus securing a succession.

Edward Hinton felt aggrieved, claiming that Chawton should be his by virtue of his status as heir-at-law, and started to make his views known. In 1741 Thomas Knight with William Guidott brought a Bill of Complaint (the first stage of a suit) in Chancery against Edward Hinton (TNA: C 11/1253/33). The plaintiffs’ case repeated the details of Elizabeth’s will whereas Hinton’s claim rested on his being the right heir. Hinton failed to appear in court to support his claim, and the case was lost by default.

In April 1757 Thomas Knight undertook the process of a Common Recovery in order to transfer property; the entail was broken and his estates settled in favour of his son, Thomas Knight (Junior), then aged twenty-one (HRO:17M48/130). The process allowed the estates to be conveyed to trustees so that technically the trustees were the legal owners on behalf of the tail (the beneficiary). Involved in this process as trustees were John Woodroffe and his wife Mary (William Guidott’s niece and heir-at-law) and Francis Austen of Cliffords Inn. A further settlement took place in 1779 when Thomas (Junior) married Catherine Knatchbull. In a strict settlement, a new entail was created in each generation, either when the eldest son reached twenty-one or was married. The marriage settlement ensured that the estate was protected until the unborn son reached the age of majority. At the same time provision was made for the wife’s jointure (received if she was widowed) and any distribution to other children (on reaching twenty-one or marriage) (Habbakuk, “Marriage Settlements”). Settlements were a drain on the estate. Jointure, allowances to the eldest son, and portions to other children reduced the profits that could be used for estate development. Protecting the future of an estate was not cheap and could affect future yields and hence profits.8 Mrs. Bennet, for instance, had a marriage settlement of £5,000, equivalent to £200 p.a. (at 4%) in mortgage payments on her father’s estate. By the way of comparison Darcy’s income was £10,000 p.a. and his sister’s £3,000.

Thomas Knight inherited his father’s estates two years after his marriage. Thomas and Catherine had no children, but following several years of reciprocal visits between Godmersham and Steventon, they formally adopted Edward Austen in 1784. Edward, treated as a son, had an allowance which enabled him to go on an extended European tour, rather than go to University like his brothers James and Henry. When Thomas Knight died in 1794, his three main estates passed to his widow, Catherine, for her lifetime. The estates were in the legal ownership of trustees: William Deedes the elder, William Deedes the younger, and Nicholas Cage, of whom only William Deedes the younger was still alive.9

Although Austen had started work on Lady Susan and the characters of Elinor and Marianne, later to appear in Sense and Sensibility, within two years of Thomas Knight’s death the creation of the Bennet family and their legal problems took precedence in her mind. There has been much speculation about how much Jane understood about entail and settlement featured in her novels.10 Her use of entail and settlement appears inconsistent; maybe she is reflecting common understanding, or perhaps she is seeking to tease or confuse the reader. Peter A. Appel has argued that scholars are also confused (625-26). Although the use of settlements replaced the simpler entails, there would have been a time lag. Both inheritance conditions would have been in existence in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, causing confusion as to whether someone could or couldn’t have prevented a family’s being turned out of their home.

In Pride and Prejudice, Mrs. Bennet’s claim that Mr. Bennet could do something to ensure that his daughters would not be disinherited may have had some validity. The time to act would have been before Mr. Bennet’s father’s death when father and son could have collaborated to bar the entail. But few would have the foresight to take action in case there were no male heirs. Mr. Bennet had only a life interest, and Mr. Collins had a vested interest as a remainder man. The minor rift between Mr. Bennet’s and Mr. Collins’s fathers is not known, but Redmond speculates that it originates in the running of the estate (46-52). With no male heir, succession would have reverted to the default position, where lineage would be traced back to the original donor and the right heir, an heir-at-law by blood, found. In Sense and Sensibility, a different scenario is given. Old Mr. Dashwood settles his estate not on his nephew Henry, who could be regarded as his right heir, but on his nephew’s son, John, and then John’s heir. In Persuasion, Sir Walter Elliot had financial difficulties, the land was mortgaged, and he was reluctant to sell any of it.

Although landowners exchanged parts of estates to benefit their estates, or an owner sold remote parts so as to raise the capital to consolidate or improve their main estate, for Sir Walter only a small part could be sold. Chawton was likewise protected and could not be disposed of under the terms of Elizabeth Knight’s will. Any land sale would need to be agreed to by those who had a vested interest—the remainder men. In 1811, Thomas Knight’s widow, Catherine, and Edward Austen sold part of the Knight estate—Abbots Barton in Winchester—to raise capital for the building works on the main estates (Grover, “Edward Knight’s Inheritance”). Abbots Barton was not covered by the settlement.

In 1798 the elderly Catherine asked Edward to take over the management of the estates subject to a rent charge of £2,000 p.a. (HRO: 13M85W/38). Jane Austen’s comments on the arrangement indicate she was fully aware of the terms of the transfer and the nature and legal process surrounding settled estates.11 This transfer was the beginning of the Austens’ legal problems, which informed and enriched Jane Austen’s novels.

How much would Jane Austen have known about these matters? The Austens were a close and social family: they ate together, they visited each other, and they socialized with friends and acquaintances. Jane Austen’s niece Caroline Austen, the daughter of James, described the family relationship and her Aunt’s position in it:

In the time of my childhood, it was a cheerful house—my Uncles, one or another, frequently coming for a few days; and they were all pleasant in their own family—I have thought since, after having seen more of other households, wonderfully, as the family talk had much of spirit and vivacity, and it was never troubled by disagreements as it was not their habit to argue with each other. . . . I don’t believe Aunt Jane observed any particular method in parcelling out her day but I think she generally sat in the drawing room till luncheon: when visitors were there, chiefly at work. (6-7)

Austen was not one to sit remote in a corner in the family drawing room: she listened, absorbed, and passed comment. There is no record of her verbal comments, but her letters reflect her knowledge and views.

During her visits to Edward at Godmersham and Henry in London, she was exposed to the business world in the same way she learned about the clergy and the navy from her other brothers. She appreciated the value of good legal advice and was very impressed by the learned counsel. While Jane Austen was staying with Henry in March 1814, she writes to Cassandra about a case involving their neighbors’ ten-year-old son, James Baigen, whose family had lived in the village for over a hundred years:

Edward has had a correspondence with Mr Wickham on the Baigent business, & has been shewing me some Letters enclosed by Mr W. from a friend of his, a Lawyer, whom he had consulted about it, & whose opinion is for the prosecution for assault, supposing the Boy is acquitted on the first, which he rather expects.—Excellent Letters; & I am sure he must be an excellent Man. They are such thinking, clear, considerate Letters. . . . I long to know Who he is, but the name is always torn off. He was consulted only as a friend.—When Edwd gave me his opinion against the 2d prosecution, he had not read this Letter, which was waiting for him here. . . . Now I have just read Mr Wickham’s Letter, by which it appears that the Letters of his friend were sent to my Brother quite confidentially—therefore don’t tell. (5-8 March 1814)

Baigen was accused of stabbing a man and was tried at Winchester in March 1814. Edward had sought help from the Hon. William Wickham, who had an estate just outside Alton, and Wickham had approached an eminent lawyer for advice. Baigen was acquitted (Durey).

In Austen’s novels, the shortcomings of country solicitors and attorneys are a recurrent theme. In Pride and Prejudice, they are derided, deemed not socially acceptable and a source of mirth. Their relatives are found wanting (Treitel). Austen’s stance reflects her family’s traumatic experiences of the law and their view on local legal advisers of their adversaries. In Persuasion, written during the period when the threat to Edward’s inheritance was gaining momentum, Mr. Shepherd’s convoluted style mimics the theatrics involved in the process of Common Recovery.

To what extent Jane Austen was allowed free access to Edward’s correspondence is not known, but she certainly wanted to keep Cassandra informed. Austen was fully aware of both Henry’s and Edward’s legal problems, listening and participating in family discussions both at Chawton and while on her extended visits to Henry in London in 1814 and 1815. Updating Cassandra with the latest news, she records that Henry “read me what he wrote to Edward; —part of it must have amused him I am sure—one part alas! cannot be very amusing to anybody.—I wonder that with such Business to worry him, he can be getting better” (24 November 1815). The Knight archives at Hampshire Record Office contain large bundles of legal documents. Estate and business histories are recorded in great detail; copies of correspondence to and from lawyers and solicitor were kept. Austen probably had access to them either at Godmersham or later at Chawton when Edward and his family moved there.

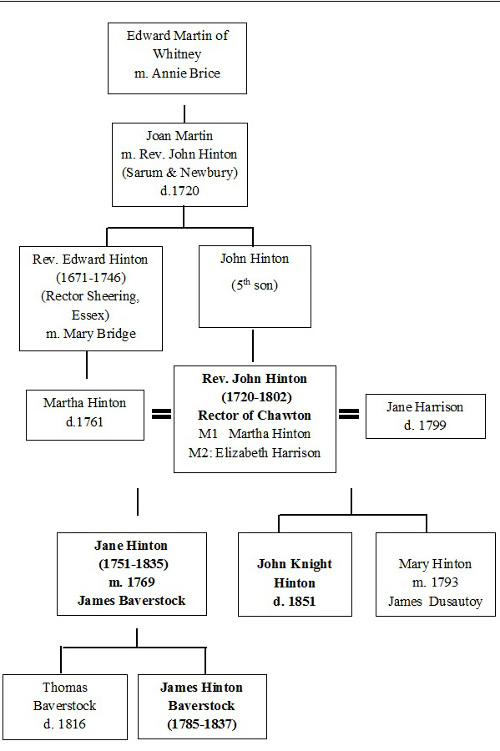

The Hintons’ claims to Elizabeth Knight’s property did not end with Edward Hinton’s failed claim. Table 2 shows the family tree of Rev. John Hinton, rector of Chawton, who married twice. By the first marriage to his cousin, the daughter of Rev. Edward Hinton of Sheering in Essex, he had a daughter Jane. Jane married local Alton brewer, James Baverstock.12 They had two sons, Thomas and James, who both followed their father’s business, and a daughter, Frances. John Hinton’s second marriage to Jane Harrison produced one son, John, and three daughters, one of whom married James Dusautoy.

The first seeds of discontent in the Baverstock household may have dated back to Edward’s adoption in 1784; his extended visits to Godmersham would not have gone unnoticed in Steventon and Chawton. Godmersham was never part of Elizabeth Knight’s empire, but the Chawton and Winchester estates produced a substantial income. After Thomas Knight’s death, the feeling of injustice that Edward Austen was set up to take what was rightly a Hinton’s inheritance grew. While Catherine Knight was alive, there was little opportunity for legal redress, but as Edward took over the management of the estates, the decision to take legal advice was made, questions were asked, and evidence collected. Family papers would have contained Edward Hinton’s claims. It is unlikely the Austens were unaware of these feelings of injustice especially since attempts to pursue them were started straight after Elizabeth died by Jane Baverstock’s grandfather. In 1812 Catherine died, and Edward claimed his inheritance and, as required by Elizabeth Knight’s will, changed his name to Knight.13 Within two years, John Knight Hinton and Jane Baverstock had begun legal proceedings to claim what was, in their opinion, rightly theirs. Edward had been adopted and therefore was not an heir of the body. In their view he did not satisfy the conditions of the settlement, unlike the direct descendants of Rev. John Hinton—Elizabeth’s heirs-at-law—Jane Baverstock and John Knight Hinton.

Henry’s entrepreneurial plans and the collapse of his bank must also have soured the Austens’ relationship with the Baverstocks. Henry, somewhat of a wine buff, planned to start a brewery in the West End of London, but the plan was abandoned in 1809 although the viability of the venture was uncertain when Jane Austen comments, “The brewery scheme is quite at an end” (15-17 June 1808). Baverstock’s views are made transparent in a pamphlet where he tries to “dissuade private families and inn-keepers from making their own beer, in order to increase the business of public breweries” (Rev. of Practical Observations). Such a plan could have had an impact on the Baverstocks’ business in Alton and in Windsor, where James Baverstock’s son, Thomas, had built up a sound trade with London. Henry’s plans for the Old English Ale Brewery were not approved of by some of those established in the brewing trade.

The first recorded trouble involving the Baverstocks and Henry Austen started in November 1813 and culminated in a legal case tried at the Lent Assizes in Winchester in June 1816 brought by Portsmouth bankers Grant & Binbey against Austen & Co. to recover £59 15s (Troubat 284-89). The plaintiffs received a cheque from Baverstock and Son, brewers of Alton, drawn on a Mr. Gray’s bank in November 1813. The Alton bank was known as Austen, Gray, and Vincent, but although Henry had left the partnership in 1811, in the Baverstocks’ minds his name was still linked with the business.

Gray did not have the funds and was overdrawn with his London agents, Austen, Maude, and Tilson. With increasing likelihood of bankruptcy, Gray misappropriated funds to pass to family members. Baverstock’s cheque was not honored, no doubt causing considerable embarrassment to him in the business community when suppliers were not paid. The Baverstocks would have lost money as Gray’s bank collapsed. Bankers did not have an obligation to honor the cheques of those lacking in funds. Banks had unlimited liability.14

The legal battle over the ownership of Chawton was more extensive and complex than indicated in comments in Jane’s surviving letters although they give a sense of the seriousness of the challenge and the impact on the family. In her letter to Cassandra written in Henrietta Street dated 5-8 March 1814, Austen writes, “It is a nasty day for everybody. Edward’s spirits will be wanting sunshine, & here is nothing but Thickness & Sleet.” Later she adds, “Perhaps you have not heard that Edward has a good chance of escaping his Lawsuit. His opponent ‘knocks under.’ The terms of Agreement are not quite settled.” Whether an agreement was reached is not known; either there was a stalemate, or there was some agreement as to what the legal process was to be and the expected outcome. In October 1814, two writs of entry were served by John Knight Hinton and James Baverstock and his wife Jane whereby they claimed they were disseised (wrongly deprived) of the land (HRO: 13M85W/41).3 Edward consulted his lawyers in London: Edward, Jane Austen wrote, “is likely to come here on Tuesday next, for a day or two’s necessary business in his Cause” (17-18 October 1815). The family rallied around, and the Knights, Bridges (Edward’s in-laws), and Austens descended upon Chawton for a family conference (Nokes 438). Neither Thomas Knight, his son Thomas, nor Edward had adhered to Elizabeth Knight’s residency clause. There was no penalty for ignoring her wish, but as the threat to his inheritance mounted, Edward and his family moved back to Chawton, albeit while Godmersham was being renovated. There was pressure on Hinton and Baverstock to start the court case before Edward’s son reached the age of majority in 1815 and the entail would be barred (HRO: 17M48/133).

What is not well known is that there was a series of legal claims on land at Chawton, Abbots Barton, Winchester (then in the hands of William Simonds), and for every piece of land belonging to Elizabeth Knight that had been sold by Thomas Knight, his widow, Catherine, or Edward Austen. The chief claimants (or perhaps they should be described as green-mailers) were Jane Baverstock and her son James Hinton Baverstock, described as a “clever and rather scampish brewer of Alton” (Le Faye, Letters 494), and Jane Baverstock’s half-brother, John Knight Hinton, and half-sister, Mary Dusautoy. Each claim contained a copy of Elizabeth Knight’s will and the Baverstocks’ relationship to Elizabeth Knight. The claim asserted that the recovery suffered by Thomas Knight the elder and Thomas Knight the younger in 1757 was defective because the stages of the process were not in the correct order and therefore not valid (HRO: 13M85W/42).

The whole affair must have been a great embarrassment to Edward, the Austen family, and his wife’s family as the writs involved people who had purchased land from the Knights in good faith, believing that the titles were sound. The claims did not reach court until after Austen’s death although she would have been aware of them. Eric Walker, in the context of the publication of Mansfield Park, points out, “Austen’s local readers in 1814 knew very well that the inheritance provisions in the Knight family adoption were not a seamlessly settled affair.” There were sixty families resident in Chawton, most of them employed on the estate. After Rev. Hinton’s death, John Rawston Papillon and his sister moved into the rectory, and the Hintons and the widowed Mrs. Baverstock lived at Chawton Lodge. As his sister remarked, Edward’s “hopes . . . in his Cause, [did] not lessen” (29 November 1814).

In 1786, Thomas Knight had sold a sizeable plot of land in Lyminster in West Sussex to Charles Goring of Winston for £7,947.10s. This transaction appears to be the basis for the first claim brought in 1816 by John Knight Hinton, Jane Baverstock (then a widow living in Alton), and her two sons Thomas (by then located in Windsor) and James Hinton Baverstock. They argued that the entail was not barred by the recovery of 1757.15 As “remainder men,” they had an interest in the land and had not agreed to any sale. With a payment of £1,000 from Goring, however, they were willing to release their interest. Goring agreed. Not until 1825 was the legal process completed: it required the making of a tenant to the praecipe (a third party to transfer the land to trustees), followed by a Common Recovery (transfer of land to rightful owner), and a fine—all to ensure that Goring had a water-tight title.16

In April 1818, John Knight Hinton and Jane Baverstock brought the main case against Edward for the Manors of Chawton, Alton Eastbrooke, Steventon, and Shalden. The claim was based on timing—that the order of legal procedures was invalid.17 They must have been sure that this complaint would be upheld in court as they did not raise the issue that Edward was not an heir of the body, which would also have invalidated the entail. There was a weakness in Jane Baverstock’s claim. The tail male lineage had stopped at her, and therefore her sons had no rights, nor would her husband. However, the son of the Rev. Hinton, John Knight Hinton, did have rights.

To avoid further litigation, Edward Knight was forced to acknowledge the claim and pay Baverstock and Hinton the sum of £15,000, of which two-thirds went to Jane Baverstock and one-third to John Knight Hinton. To pay this large sum in the wake of the financial costs from the collapse of Henry’s bank, a substantial area of timber was felled that, according to a niece writing a half century later, “occasioned the great gap in Chawton Wood Park, visible for 30 years afterwards, and probably not filled up again even now” (Austen-Leigh and Knight 171).

The third claim was against William Simonds, who had purchased Abbots Barton Farm18 from Edward Austen and Catherine Knight in June 1811 for £33,670. Simonds had not been in possession of the land for sufficient time to claim ownership through adverse possession. To avoid further litigation, he agreed to purchase “a release of all the right whatever it may be of and were formerly the estate of Elizabeth Knight for the price of £650, one third to be paid to John Hinton Knight and two-thirds to Jane Baverstock, for absolute purchase of their respective rights, tithes and interests” (HRO:13M85W/41,42). The legal work was resolved quickly with a Common Recovery executed in November of that year.

A fourth claim, also in June, was against William Portal of Ashe in respect to Rookery Field, Steventon. In 1797, Deedes and Cage (Thomas Knight’s trustees) with the consent of Catherine Knight sold 28½ acres of land for £644. The land was leased to Hugh Digweed. William Portal, then living at Laverstoke, had been satisfied of the validity of his title but to avoid further litigation agreed to pay £175 to Baverstock and Hinton (HRO:5M52/T163). The final claim for which a record can be found was for Foster House Farm, Surrey, where Edgell Wyatt Edgell paid £380 to ensure good title (SRO: 548/3/3/9).

Although Pride and Prejudice was published before the Hinton and Baverstock case reached court, the nature of the claim and possible outcomes would have been known from the time Edward changed his name to Knight and, as far as the Hintons and Baverstocks were concerned, grabbed their inheritance.19 As the family tree of Elizabeth Knight indicates, there were many distant relatives, including heirs-at-law, but luckily for Edward Knight and those who purchased part of the Knight estates they “did not all want to assert their claim” (Austen-Leigh and Knight 171).

All this litigation was costly to all parties involved, including to those who had bought land from Edward Knight in good faith and had peaceful enjoyment for several years. Lawyers were employed to gather together all of the Knights’ legal documents dating back to Elizabeth Knight’s will and produce pages of evidence. Coming so soon after Henry’s bank collapse, which incidentally involved a bounced cheque belonging to James Baverstock, both the financial and psychological effects on the Austens were immeasurable. Edward’s case was not resolved until after Jane’s untimely death. The effects on the Baverstocks were also high: James Baverstock died in 1815 after a period of ill health, and James Hinton Baverstock went bankrupt in 1821.20

How are the threats to Edward’s inheritance reflected in Austen’s writing? Pride and Prejudice contains a message to those who want to unseat her brother from his inheritance and turn them out of their home. Her hope was for a solution that would not be injurious to either party. MacPherson shines a light: “Pride and Prejudice is an argument about short- and long-term obligations: an argument on behalf of a model of obligation whose durability and impersonality, whose extension through time and social space, is enabled by the technology—at once conceptual and historical—of entailment” (2).

It is not clear whether Austen leans towards empiricism or rationalism (Bonaparte). Austen spent considerable time revising the first half of Pride and Prejudice before its publication in 1813. Some twelve months before the first court case, she is either sharing her thoughts or arguing that neither Edward, the Austen family, or the Hintons and Baverstocks are to blame for the situation they find themselves in. The Austens were hoping for a sensible resolution to the dispute and tried to remain on amiable terms with their neighbors at Chawton Lodge (Letters 23 June 1814; Nokes 457).

The resulting subtext is either a heartfelt message, propaganda, or a mixture of both addressed to their neighbors who were bringing the claim that could have resulted in Edward losing Chawton. The estate would be entailed away from his children, and Jane, her mother, and sister would be evicted from the cottage where they had eventually settled happily after her father’s death. Entail damned the “family of females to a future of poverty and displacement, a seeming triumph of the law of property over Austen’s notion of justice and common sense” (Appel 612). Austen’s authorship of Pride and Prejudice was not publicly known initially although some of her friends quickly guessed. This recognition may have been advantageous if Austen was trying to influence Edward’s challengers and/or sway local views.

The deep seated injustice felt by the Hintons and Baverstocks had its roots in the tension between Edward Hinton and Thomas Knight seventy years before. Austen seems to think that they should be more like Mr. Collins, apologizing for the stress and upset they were bringing on the Austen family. Heirs rarely refused an inheritance; a peaceful agreement needed to be reached. Edward had been groomed to take over the estate, managing in collaboration with Mrs. Knight for several years after his European tour. He would nurture and protect Chawton. On the other hand, although like Mr. Bingley respectable, the challengers’ fortune had been acquired through trade, the brewing business.21

The history of the Hinton and Baverstock claims suggests an arrogant assumption that their claim must be just: they are the heirs-at-law with no recognition of the validity of the testator’s will. Their claim and evidence are presented on numerous occasions in courts of law, yet they fail in their endeavors, and their financial gain is limited in comparison to personal and monetary costs.

Did Austen and her readers understand the nature of entail and settlement? Appel argues that the possibilities either that Austen understands and her audience does not or that she does not understand and her audience does are unlikely. He concludes that ignorance of entail and settlement on both sides is most likely and that knowledge on both sides is possible and interesting. He surmises that “[a]lthough Austen was an astute observer of society, her commentary on that society using the device of common recovery when her audience was clueless would have had to be extremely ironic or clairvoyant” (632). In reality, there are degrees of knowledge, shades of understanding. Austen’s readers were her family, friends, neighbors and acquaintances, the gentry, the Prince Regent, and her family’s foes. Austen sought to know what they thought of her novels and shared opinions of Pride and Prejudice in letters to Cassandra. She cared what people thought of her ability as a writer, and, in this instance, was anxious that her readers were sympathetic to her family’s dire situation. MacPherson hypothesizes that “Land law, rather than marriage or class, is the ground upon which Austen works out the way in which persons are, and ought to be, connected to others” (2).

Austen’s access to family history, oral and written, Edward’s and Henry’s court cases, and the inclusiveness and the equality of females in the Austen family, all firmly suggest that she fully understood land ownership and financial issues. Elizabeth and Jane in Pride and Prejudice held a similar position. What of Austen’s audience? Her family, her friends, and their foes would understand. Gentry families were extensive, with many interrelated branches of cousins with numerous estates, and, thus, the legal processes would be well known and understood. Relatives of Austen’s mother, the Leigh family, were involved in litigation about seemingly unfair wills (Hildebrand 34-41). Family history and questions of who was related to whom were important, especially in an age where, although marriages were not arranged in the sense they are in some societies, the importance of a good marriage was measured in terms of money, status, and land ownership. The future of a family’s estates was seen as a sensitive management decision.

In 1833 the Fines and Recovery Act abolished the process of Common Recovery. The legal system was cleansed of that theater, and the earnings of lawyers were curtailed. The complexities and vagaries of English land law are summed up five years later by Oliver Twist’s Mr. Bumble, who stated that “the law is an ass—an idiot.” It could be said that a man inheriting from distant relatives is in want of a good lawyer. Land law was the bane of families but a rich lode for Georgian authors. Land law is complex, but Austen understood it and drew on it, not only to advance her plots but to influence her audience.

Notes

1. Sources from The National Archives (UK) will be cited parenthetically with the initials TNA followed by the reference number. Sources from the Hampshire Record Office and Surrey Record Office will be cited parenthetically with the initials HRO or SRO followed by the reference number.

2. For more details on Elizabeth Knight and her descendants see Christine Grover’s “Edward Knight’s Inheritance: The Chawton, Godmersham, and Winchester Estates” and Hyde: From Dissolution to Victorian Suburb.

3. In a letter to Jane Austen, Edward’s daughter Fanny comments, “We are therefore all Knights instead of dear old Austen, How I hate it!!!” (Letter 52, qtd. in Nokes 395).

4. The brother-in-law was in fact his step brother. His father had died when he was only two, and his mother married Azariah Husbands of Horkesley Hall in Essex.

5. She begins her will by leaving sums of money to several relatives: Mrs. Anne Lloyd, widow of the Rev William Lloyd (Rector of Chawton, 1714-1718), their son William (attorney at Newberry [sic]), and two of her daughters; Rev. John Baker; and Rev. Edward Hinton, eldest son of Rev. John Hinton (Rector of Newberry). Further sums are left to servants and the poor of ten parishes in her estates (TNA: PROB 11/688/170).

6. The livings of Chawton and Steventon were under the patronage of the owner of Chawton House. Relatives were favored for these posts: Rev. George Austen was related to Thomas Knight.

7. The will states: “To John Hinton, son of John Hinton (late attorney of Newberry) in the hope that he will be a scholar and take holy orders in the Church of England according to his father’s desires and if he does so and proves a sober and good man, then instruct trustees to present him with the gift of the two parsonages at Chawton and Steventon.”

8. See Thorold Rogers. In an example, a landowner with a rental income of £7,000 might be left with £2,400 (34%) after maintenance costs, payments to family members, and interest on mortgages raised for marriage settlements.

9. Both Lewis Cage and William Deedes were brothers-in-law to Edward Austen by their marriages to Sir Brook Bridges’s eldest two daughters, Fanny and Sophia.

10. See articles by Hildebrand, Treitel, Redmond, MacPherson, and Appel.

11. “Mrs Knights giving up the Godmersham Estate to Edward was no such prodigious act of Generosity after all it seems, for she has reserved herself an income out of it still;—this ought to be known, that her conduct may not be over-rated.—I rather think Edward shews the most Magnanimity of the two, in accepting her Resignation with such Incumbrances” (8-9 January 1799).

12. James’s father had built the brewhouse in Turk Street, Alton, in 1763. In 1786 James moved to Windsor to set up a brewery selling beer to London. In 1801 his son Thomas took on the business, and James returned to Alton to run the brewery there. James is noted as the first person to use a hydrometer in beer production. In bad health, he died in 1815 during the legal wrangle. The Alton brewery was sold in 1821.

13. In Pride and Prejudice, either Mr. Collins or his father must have undergone a name change to be an heir to the Bennet fortune.

14. In March 1816, Henry Austen was to follow the same fate. Edward Knight and other family members, as guarantors, lost considerable sums of money. Jane Austen herself did not go unscathed (Corley 139-50). Tilson was a frequent visitor of the Austens and lived next door to Henry in Hans Place, Westminster (Le Faye, Family Record 228; Letters 22 August 1814). Undoubtedly, during many conversations, he shared his banking knowledge and stories with Austen.

15. Details of the April 1757 “Deed of Covenant to levy a fine on Chawton and lead to uses to settle the estates devised by Elizabeth Knight” are found in HRO:17M48/130. Details of the subsequent Bargain and Sale between Thomas Knight (senior and junior) and Francis Austen are found in HRO:5M52/T163.

16. West Sussex Record Office: WINSTON/2020-2027.

17. William Austen-Leigh and Montagu Knight describe the problem as “some informality in a disentailing deed executed in 1755” (171).

18. At the time of the sale, the farm included the former Hyde Abbey Farm, which was not part of Elizabeth Knight’s lands.

19. It should be remembered that Godmersham was not part of Elizabeth Knight’s inheritance.

20. This case was not the end of James Hinton Baverstock’s litigation career. In 1834 he initiated another claim over copyhold lands in Essex, which had been invested in John Hinton for life (Nevile and Perry 648-70). James Hinton Baverstock died in 1837 just before his claim reached the law court.

21. I am indebted to MacPherson for these points in the context of Pride and Prejudice.

Works Cited

Appel, Peter A. “A Funhouse Mirror of Law: The Entailment in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.” International and Comparative Law 41 (2013): 609-36. Austen, Caroline. My Aunt Jane Austen: A Memoir. Winchester: Jane Austen Society, 1991. Austen, Jane. The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Jane Austen. Gen. ed. Janet Todd. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2009. _____. Jane Austen’s Letters. Ed. Deirdre Le Faye. Oxford: OUP, 1995. Austen-Leigh, William, and Montagu Knight. Chawton Manor and Its Owners: A Family History. London: Smith, Elder, 1911. Available online at https://archive.org/details/chawtonmanoritso00austuoft Bonaparte, Felicia. “Conjecturing Possibilities: Reading and Misreading Texts in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.” Studies in the Novel 37.2 (2005):141-61. Corley, T. A.B. “Jane Austen and Her Brother Henry’s Bank Failure 1815-16.” Jane Austen Society Collected Reports (1996-2000): 139-50. Durey, Jill. A Stabbing in Chawton, Jane Austen, and Emma. Perth, Australia: Edith Cowan UP, 2011. Grover, Christine. “Edward Knight’s Inheritance: The Chawton, Godmersham, and Winchester Estates.” Persuasions On-Line 34.1 (2013). _____. Hyde: From Dissolution to Victorian Suburb. Winchester: Victorian Heritage, 2012. Habakkuk, H. T. “English Landownership, 1680-1740.” Economic History Review 10.1(1940): 2-17. _____. “Marriage Settlements in the Eighteenth Century.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 4th ser., 32 (1950): 15-30. Hildebrand, Enid G. “Jane Austen and the Law.” Persuasions 4 (1982): 34-41. Le Faye, Deirdre. Jane Austen: A Family Record. Cambridge : CUP, 2004. Le Faye, Deirdre, ed. Jane Austen’s Letters. Oxford: OUP, 1995. MacPherson, Sandra. Rent to Own: Or, What’s Entailed in “Pride and Prejudice.” Representations 82 (2003): 1-23. Nevile, Sandford, and Thomas Erskine Perry. Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Court of King’s Bench: And Upon Writs of Error from that Court to the Exchequer Chamber [1836-38]. Vol. 3. London, 1838: 648-70. Nokes, David. Jane Austen: A Life. London: Fourth Estate, 1997. Redmond, Luanne Bethke. “Land, Law and Love.” Persuasions 11 (1989): 46-52. Rev. of “Practical Observations on the Prejudices against the Brewery: Wherein the True Principles of the Process, with the Causes of the Uncertainties Experienced by Private Families and Others in Brewing Are Pointed Out.” The Monthly Review Oct. 1812: 218-20. Troubat, Francis J., ed. Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Court of Exchequer, at Law and in Equity, and in the Exchequer Chamber in Equity and in Error. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, 1835. 284-89. Thorold Rogers, James Edwin. Primogeniture and Entail: Letters of J. E. Thorold Rogers. Knowsley Pamphlet Collection. Liverpool, 1864. Treitel, G. H. “Jane Austen and the Law.” The Law Quarterly Review 100 (1984): 549-86. Walker, Eric C. “In the Place of a Parent.” Persuasions On-Line 30.2 (Spr. 2010).

|