AMONG JANE FAIRFAX’S LIST OF POLITE ACCOMPLISHMENTS are a knowledge of Italian and an ability to sing in that language. The reader is aware of Jane’s abilities in this regard, of course, because of a comment by Harriet Smith. In attempting to praise Emma’s music-making at Jane’s expense, Harriet adds, “‘And I hate Italian singing.—There is no understanding a word of it’” (232). Thus, Jane belongs to that elite group of Austen characters who are familiar with the Italian language and/or Italian music, a group that also includes Caroline Bingley (PP 51) and Anne Elliot (P 186).

Italian opera may seem to be worlds away from Austen’s unpretentious domestic dramas set in the English countryside, even antithetical to her worldview. The stereotypical associations of the art form—over-the-top emotion, gigantic egos, and conflicts both on and off stage—have led to the pejorative modern meaning of the word “melodrama,” which originally was simply another name for opera. The novelist Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa observed of Jane Austen that she is “l’anti-melodramma, the antithesis of opera” (147-48). Linda Zionkowski and Mimi Hart, among others, have stressed Austen’s decided preference for modest, domestic music-making over the pretentions of virtuosic professionals. Any investigation of Austen’s novels and letters renders such a conclusion indisputable. Nevertheless, as the work of Jocelyn Harris, Janine Barchas, and others has demonstrated, Austen was well aware of the outside world, and she deals with current events and contemporary celebrities, however obliquely, in her writing.

The music of the Italian opera made its way to English drawing rooms in Austen’s day as did stories of the clashing temperaments of singers. Italian opera in London was a hotbed of gossip, intrigue, clashing temperaments, and competition between singers. Just as its music made its way to the English countryside, so too did news and gossip about opera singers. The rivalries of historical professional singers echo the domestic music-making of Austen’s fictional characters. We will examine some famous diva rivalries of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and investigate the ways in which Austen would likely have known of them. Though Emma contains perhaps more musically talented characters than any other Austen novel, we will concentrate on the female characters, or divas, of Highbury—Emma herself, Jane Fairfax, and Augusta Elton. Not only do the rivalries of famous divas make their way into the plot and characterization of Emma, but they also contribute to Emma Woodhouse’s process of growth throughout the novel.

Italian opera in London

By Austen’s time, Italian opera had long been established in London as a distinguished, if sometimes controversial, art form. Beginning in the late seventeenth century, the British capital was able to attract some of the best composers and the biggest stars. There was a concurrent trend toward establishing English-language opera, and by Austen’s lifetime the two forms existed (almost) side by side. The Licensing Act of 1737 divided the theater venues into different areas of specialization: Italian-language opera could only be performed at the King’s Theatre in the Haymarket (the company was known as the Italian Opera), while the Theatres Royal at Covent Garden and (occasionally) Drury Lane presented English-language popular melodramas and ballad operas as well as spoken plays (Price, Milhous, and Hume 52-54). The aristocracy generally favored Italian opera, with its more cosmopolitan cultural cachet, while the broader “middle class” public favored the English ballad opera (Scott 16). As we will see, however, that divide did not preclude educated and aspiring middle-class amateurs from performing Italian operatic selections at home. After all, Italian is presumably one of the “modern” languages that Miss Bingley mentions as part of the repertoire of the accomplished woman (PP 39), and Italian opera could be known and admired even by people who did not attend the King's Theatre on a regular basis.

Italian opera was controversial in Britain: it was considered dangerously “foreign,” expensive, and elitist (Scott 16), and for most of the eighteenth century, it involved the use of castrati, adult male singers who had been castrated as boys to preserve their soprano or contralto voices. By the time of Austen’s adulthood, the castrato phenomenon was winding down, and female prima donnas, formerly often considered secondary attractions to the castrati, were taking over as the biggest and highest-paid stars of opera (Price, Milhous, and Hume 592-93).

In the eighteenth century, the term prima donna (“first woman”) was an official title in opera companies, corresponding to the primo uomo (“first man”), who was invariably a castrato (E. Harris). The use of the term diva (“goddess”) slightly postdates Austen’s lifetime; it was apparently first applied to the Italian soprano Giuditta Pasta in the 1820s (Davies 126). It was not until the middle of the nineteenth century that the term “prima donna” began to be used pejoratively, but, as we will see, the kind of highly-strung, demanding behavior stereotypically associated with opera singers was already notorious (Christiansen 9). The term “diva” has taken on similarly negative connotations, akin to the more recent equivalent, “drama queen.”

Rupert Christiansen has argued that the negative stereotype of the prima donna or diva is unfair:

Opera has always been a highly-strung profession, running on dynamic and creative clashes of will and temperament. Given such a gamble in such circumstances, a woman had to be alert and aggressive to survive. “Acting the prima donna” may have been the only way to avoid exploitation, and a prima donna’s greed was often the hard-headed refusal to work for less than her market value. Her celebrated whims, too, often had solid reasoning behind them. . . . A woman who refuses compromises is a prima donna. A woman dedicated to her talent is a prima donna. (10)

At first glance, professional singers’ reputation for whims and aggressiveness may not have much to do with the more modest ambitions of Austen’s amateur performers. Her characters, however, as women in a male-dominated society, nevertheless confront some of the same challenges faced by professionals. These challenges can be seen in the plot of Jane Fairfax, who is almost forced to become a paid professional teacher (if not, strictly speaking, a performer). Jane may have the talent of a professional musician, but she lacks the aggressiveness Christiansen refers to as “the only way to avoid exploitation.”

Like Jane Fairfax, many amateur performers were talented and well trained; if the virtuosic nature of the music made available for domestic performance is any indication, many amateurs must have been very capable indeed. In a society in which the earning of money through trade was often looked down upon, the term “amateur” did not have the pejorative connotations it would later acquire. In addition, not only did these amateurs perform music written for the great stars, they were also aware of the operatic politics of the capital. With the rise of music-making in the home, its display gradually became a “proof of social distinction for the upwardly mobile” (Scott 1), a vehicle for attracting marriage partners, and a respectable family entertainment.

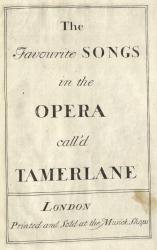

An aspiring Jane Fairfax would have a goodly selection of opera available to her to play at home. While English imprints were not printed in complete vocal scores as they would be later, starting in the 1720s excerpts from Italian operas were printed individually or in sets of “Favourite Songs.” Excerpts from Handel’s operas were particularly popular, and such sets were released throughout the century, particularly those “as sung by” the most famous singers of the time. While the “Favourite Songs” sets had waned in popularity by Austen’s time (Burden 83), publishers had begun to issue opera excerpts outside the “Favourite Songs” series, from both Italian and English operas of the day. By the end of the eighteenth century, opera excerpts occupied a large share of the ever-expanding market of music publishing, and each of these excerpts was self-consciously identified with a famous singer, reinforcing their name recognition.

|

|

|

| Title page and page 3 of Favourite Songs from Handel’s Tamerlano, highlighting Cuzzoni’s role. London, ca. 1725. M1505.H26 T3 1725. Houghton Library, Harvard University. |

||

Hampshire Chronicle 4 Oct. 1779: 4. British Library Newspapers. (Click on image to see a larger version.)

Conventional wisdom ascribes much of this burgeoning of Georgian domestic music publishing to the rise in the availability and affordability of the piano, but David Hunter cautions us that growing aristocratic populations and increasing market saturation would achieve the same result (751-53). Regardless, evidence clearly shows that music was printed in expanding numbers to meet rising demand and was easily available to wealthier Georgian consumers in London and the provinces from a variety of sources. Chiefly printed in or near London, then most likely shipped by canal or river to shops and circulating libraries in the provinces, arias, songs, and piano music might be purchased for about two to five shillings at local music shops (depending on the number of pages: paper was always the highest expense).

To put the cost of sheet music into perspective, some comparisons to other contemporary costs and expenses may be enlightening. In 1804, the year excerpts from Peter von Winter’s Il Ratto di Proserpina were printed, a highly skilled London craftsman would earn little over 4 shillings for a full day’s work (Allen). While music access was increasing, it is unlikely that domestic music-making had yet become easily affordable beyond the wealthiest class; as with books, circulating libraries were far more attractive for the average music lover. Austen was herself a subscriber to circulating libraries.1

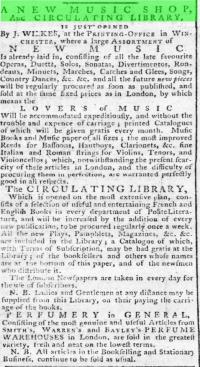

Austen’s use of music circulating libraries is less well documented, but equally likely. One possible local candidate was the music library that opened in 1779 in Winchester, the home of Austen’s piano teacher George William Chard. J. Wilkes’s Winchester library served as an agent of the London publisher J. Bland and stocked a considerable selection of music, as can be seen in their 1782 ad. For a deposit and an annual fee, subscribers would usually be entitled to borrow one score at a time (printed or manuscript), which would have to be replaced if damaged. For a higher deposit, more scores might be borrowed at the same time; most fortuitously for Austen, scores might be mailed to remote users for carriage fees.2

Sample catalog of Wilkes’s music circulating library. Hampshire Chronicle 2 Sept. 1782: 4. British Library Newspapers. (Click on image to see a larger version.) |

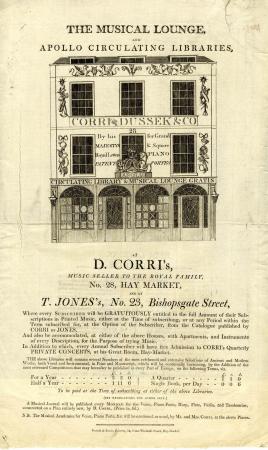

Domenico Corri’s music circulating library in London (1801 or 1802). Printed by Brettell & Bastie. Courtesy of Claire Bellanti. (Click on image to see a larger version.) |

J. Bland’s advertisement gives the annual fee as £2.2 (provincial rates likely varied). This model must have suited the industry well, as most music circulating libraries were associated and often housed with music shops. And why not? Patrons might be more easily enticed to buy music they had borrowed and liked.

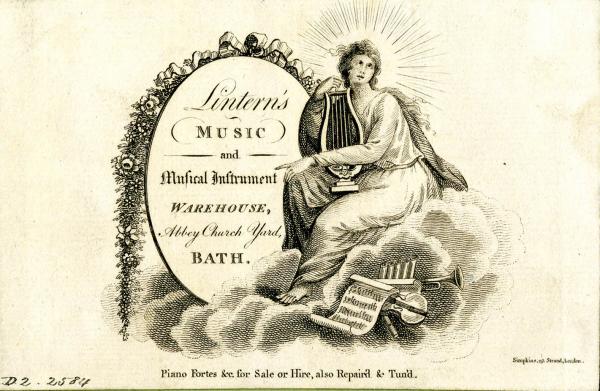

Music shops and circulating libraries often provided demonstration, sales, rental, and repair of musical instruments as well as local concert tickets; sometimes they also housed a concert venue. Matthew Spring mentions the music shops in Bath as a place for musicians to gather and for students to connect with teachers (5); they could also be a place for enterprising hostesses to hire dance bands. Some shops even advertised “apartments for practice” (King 135), providing one-stop shopping for the domestic and professional musician.

Trade card, Lintern’s Music and Instrument Warehouse, Bath. London: Simkins, ca. 1790-1802.

© Trustees of the British Museum.

Shops and libraries also maintained manuscript copies of music in stock; even in the early 1800s, some consumers still preferred these to the “alien appearance of the printed note” (Lenneberg, On the Publishing and Dissemination of Music 76). In fact, Lenneberg outlines a thriving market of music copying parallel to the rise of printed music in this era (76-82, 106-107; “Early Circulating Libraries”), rather like our current world of co-existing printed and digital matter. A patron might borrow a score and copy it out by hand at home or engage a copyist in the shop or library to copy it for a fee by the page. Friends might share music and copy out what they liked.

Austen’s own music library contains both printed and manuscript music, some in her own hand. Zionkowski and Hart suggest that for Austen, domestic music was a part of “the maintenance of a rich domestic life lived among friends and family, in which music allows for communication, pleasure, the growth of affection and sympathy, and the comfort of being alone with one’s own thoughts and feelings” (166). Her music library displays piano music, popular English ballads and patriotic songs, and some few opera excerpts, most importantly in the two volumes understood to be in her own hand.3 Volume 2 includes “The Duke of York’s New March,” a piano arrangement of “Non piu andrai” from Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro, and the overture to Thomas Arne’s Artaxerxes, which Austen is known to have seen at Covent Garden on 8 March 1814 (Letters 5-8 and 9 March 1814). In volume 3 Austen copied some Giordani, Grétry, and even Paisiello. While not prevalent by any means, opera would appear to be a support to the aforementioned “rich domestic life.” Did it also support a curiosity for opera gossip?

“The Duke of York’s New March” (piano arrangement of “Non più andrai” from Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro) from Jane Austen’s own manuscript volume. CHWJA/19/2 Austen Family Music Books, page 35. © 2015 Jane Austen’s House Museum.

Miss Stephens as Susanna in

Le Nozze di Figaro (1825). Mezzotint by Samuel William Reynolds, after Henri Jean-Baptiste Fradelle.

© Trustees of the British Museum.

Austen’s direct experience of famous female opera singers was apparently limited, but we know of a few exceptions. She heard and was unimpressed by the English soprano Catherine (“Kitty”) Stephens, then at the very beginning of what would become a major career, in Artaxerxes at the 1814 production Austen attended. One former singer whom Austen knew socially was Antoinette de Saint-Huberty, who had been the prima donna of the Paris Opéra during the 1780s. Now the Comtesse d’Entraigues, she was living as an émigré in London with her husband (rumored to be a spy) and their son Julien. The d’Entraigues were talented musicians, but it is unclear from Austen’s surviving letters whether she heard the former diva herself sing. Referring to Henry and Eliza Austen’s famous musical party at their Sloane Street house in April 1811, Austen writes: “The D’Entraigues & Comte Julien cannot come to the Party—which was at first a greif, but [Eliza] has since supplied herself so well with Performers that it is of no consequence” (18-20 April 1811). This statement leaves open the possibility that the Comtesse might have performed had she been able to attend.

Austen could also have read accounts of famous singers in newspapers and periodicals. There is evidence that Austen was at least familiar with the Lady’s Monthly Museum, which printed articles about English opera performances and occasionally ran stories about the lives of opera stars like Elizabeth Billington, whose importance will be explored. The Hampshire Chronicle, however, was a far more likely source for the kind of diva exposure that concerns us. Robert Miles explores the likelihood of Austen’s access to the Chronicle and presents convincing evidence that she must at the very least have been an occasional reader. Miles describes the Chronicle’s general content as “melodramatic,” which certainly defines the operatic rivalries that exploded across the stage and out into the provinces. As we will see, there is at least one instance of a scandal related to a famous prima donna that Austen may well have read about in the Chronicle.

Diva rivalries

Throughout the eighteenth century and into the early nineteenth, singers were trained to perform both dazzling florid vocalism and the less ornamented, more straightforward type of singing that was thought to be more expressive of pathos (Crutchfield). Singers often excelled at either one type of singing or the other, thus making comparisons inevitable. The more “pathetic” kind of singing, with its strong connotations of sensibility, was particularly popular with audiences, and it is fair to assume that it was popular with the domestic music market.

Francesca Cuzzoni and Faustina Bordoni (ca. 1726-1728.)

© Victoria and Albert Museum.

Since connoisseurs love to make comparisons, and human beings in general love a good fight, conflicting judgments of the complementary talents of singers could be artistically edifying and provide good publicity. The prototypical prima donna rivalry was enacted by two Italian singers in London: Francesca Cuzzoni and Faustina Bordoni, the so-called “Rival Queens” of the King’s Theatre from 1726 to 1728. Although this rivalry took place much earlier in the century, it set the stage, as it were, for the diva dynamics that were still being played out in Austen’s time. Cuzzoni, already the established star, had had difficulties with the arrival of the interloper Bordoni. As with so many other artistic rivalries, what gave this competition its vibrancy and piquancy was the fact that the abilities and affects of these two great singers were complementary. Cuzzoni employed her dulcet soprano voice to convey pathos through exquisite vocal nuance, while Bordoni excelled at dazzling technical virtuosity (Aspden 302). According to legend, the animosity between Cuzzoni and Bordoni (and their fans), reached its climax with an onstage altercation during a 1727 performance. Subsequent reports that the two women actually engaged in scratching and hair-pulling were possibly exaggerated (Apsden 303-04). The eighteenth-century obsession with balancing complementary aesthetic qualities and personality traits fed the sense of rivalry between two equally talented artists.4

The diva rivalries of Austen’s time continued along these established lines. From 1804 to 1806 there were, once again, two “first women” at the King’s Theatre: the English soprano Elizabeth Billington and the Italian contralto Giuseppina (or Josephina) Grassini. Billington first conquered the London stage in the 1780s, in English opera. After a stint in Italy in the 1790s, where she was very well received, she returned to London in 1801, this time mostly appearing in Italian opera at the King’s Theatre. She possessed a pure and lovely soprano voice with a wide range and a brilliant technique. Never a great actress, she could nonetheless project considerable charm onstage, and, by all accounts, she did not have a stereotypical diva personality: a good-natured, generous colleague, she truly deserved that ultimate Austenian accolade “amiable” (Cowgill 217-18). Billington’s outward cheerfulness, however, belied a rather unhappy private life: she was married successively to two husbands (the first died just after her debut in Naples), who both mistreated her and squandered her money (Christiansen 47-48).

Mrs. Billington as Eurydice in Gluck’s Orfeo ed |

Giuseppina Grassini in the title role of Winter’s Zaïra (1806). Mezzotint by S. W. Reynolds, after Élisabeth |

Grassini made her London debut in 1804, after conquering audiences all over Italy. She was the perfect complement to Billington: Grassini’s velvety contralto contrasted well with Billington’s silvery soprano; she excelled at pathos rather than spectacular vocal display; and she was acclaimed as a fine actress. Grassini was also beautiful and sexy; she was notorious for having had an affair with Napoleon, no less, and she would later briefly become the mistress of the Duke of Wellington.

“Vaghi colli ameni prati,”

from Winter’s II Ratto di Proserpina.

London: M. Kelly, 1804.

M1508.W78 T7 1804, no. 4.

Houghton Library, Harvard University.

(Click on image to see a larger version.)

Whether there was any personal acrimony between these two “first women” is unclear. As with other feuds in operatic history, the tension may have been between their fans and the rival newspapers rather than between the singers themselves (“Memoirs of Mrs. Billington”). It is true that Billington and Grassini appeared in only one opera together: Il Ratto di Proserpina (The Rape of Persephone), a mythological-pastoral piece composed especially for them by the highly regarded German composer Peter von Winter, to a libretto by none other than Lorenzo da Ponte, the colorful character who had written several dozen libretti, including those to three of Mozart’s greatest operas: Le Nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Così Fan Tutte. By this point, Billington’s increasingly matronly appearance was felt to be more appropriate to the mother goddess Cerere (Ceres), while the graceful pathos of the character of Proserpina was ideal for Grassini (Commons 27).

Click Here to Listen

“Vaghi colli, ameni prati,” from Il Ratto di Proserpina.

Music by Peter von Winter, libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte.

Sung by Josefien Stoppelenburg and Carol Loverde; accompanied by Stephen Alltop.

Il Ratto di Proserpina was a great success, the harmonious duets of the two rival divas being particularly admired. As the writer George Hogarth later recalled, “For this and the following two seasons—as long as Billington and Grassini remained upon the stage—this opera drew crowds to the theatre, and the airs of these singers were to be found on the pianoforte of every lady who numbered among her accomplishments a knowledge of Italian music” (qtd. in Commons 28). It is worth noting that Il Ratto di Proserpina was revived at the King’s Theatre in 1815, when Austen was working on Emma; the highly talented singer and actress Lucia Vestris made her London debut in the role of Proserpina on that occasion, and excerpts from the opera were subsequently reissued (Fenner 217). One may well imagine that Jane Fairfax, presumably au courant with the latest Italian music from London, might have been drawn to the pathetic nature of Proserpina’s arias.

Despite the success of Il Ratto di Proserpina, however, Billington and Grassini never appeared in another opera together. In his later Musical Reminiscences, Lord Mount Edgcumbe blames Grassini for this situation: “Grassini, having attained the summit of the ladder, kicked down the steps by which she had risen, and henceforth stood alone” (qtd. in Commons 32). It is unclear whether Mount Edgcumbe’s comment is based on insider information or nationalistic bias against the presumed ruthlessness of foreigners. Whatever the case, there is evidence that Grassini was not completely unwilling to share the limelight with other women: she later became the mentor, co-star, and inspiration to the aforementioned Guiditta Pasta at the beginning of the latter’s career (Poriss, Changing 76).

When Billington retired from the stage in 1806, the same year that Grassini left London, their replacement as prima donna at the King’s Theatre was the biggest star of the day, the Italian soprano Angelica Catalani. Possessed of an evidently large, wide-ranging voice and a dazzling technique, Catalani was in addition generally acknowledged to be a fine actress, excelling in both tragic and comic roles (Christiansen 54). Connoisseurs admired Catalani’s coloratura ability, but she was also often criticized for stupefying audiences with her virtuosity at the expense of good taste and artistic integrity. She was probably the first singer to specialize in singing a “theme with variations,” in which straightforward, heartfelt tunes would be slathered with vocal ornamentation.

Click Here to Listen

“O dolce concento,” arrangement from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte

Sung by Josefien Stoppelenburg; accompanied by Stephen Alltop.

Angelica Catalani, arm raised in her signature pose (1807). Color stipple engraving by Samuel Freeman, after Adam Buck. |

“O dolce concento,” arrangement from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte, as sung by Catalani in Le virtuose in puntiglio. London: G. Walker (ca. 1817). M1508.M84 Z3 1817, page 4. Houghton Library, Harvard University. (Click on image to see a larger version.) |

The composer Louis Spohr, although admiring Catalani’s technique, said that her singing lacked “soul” (Pleasants 117). Discerning music lovers also complained about her preference for the work of composers of lesser merit who would dutifully compose music tailored to her talents.

Catalani also had a reputation for stereotypical diva behavior and was routinely accused of self-centeredness, imperiousness, and greed. One critic later complained that “[during] her reign not one female performer was permitted on the Opera boards [not quite true, as we will see]; foils, not companions, were what she sought” (qtd. in Fenner 215). Catalani’s husband, a French officer and diplomat named Valabrègue, was fond of telling exasperated opera house managers what he (and presumably she) felt were necessary to produce an opera: “My wife and four or five puppets—that’s all you need” (Pleasants 119). Catalani was notorious for demanding high fees, which were blamed for her temporary non-engagement at the King’s Theatre, a situation that led to riots in the theater. Dramatic descriptions of these events even made their way into the Hampshire Chronicle, which, as noted, Jane Austen most likely would have read (“King’s Theatre”).

There is evidence, however, that Catalani was more than simply a caricature of a demanding diva. Rachel Cowgill has argued that “press reports of [Catalani’s] outrageous salary demands [and] autocratic behavior . . . are prone to exaggeration, often playing on deep-seated English prejudices against imported singers” and that “her bargaining needs to be understood as an attempt to insure herself against the [King’s Theatre]’s financial insecurity [in] the harsh wartime economy” (219). One is reminded of Jane Austen’s own financial negotiations with her publishers: what might look like greed from one perspective could just as easily be seen as a demand for acknowledgment of one’s self worth. In fact, Catalani was also known for her generosity, often forgoing high fees for charity concerts (Poriss, “Prima Donnas” 50-52). It is also telling, if apparently paradoxical, that Catalani willingly shared the King’s Theatre stage with the fine English soprano Maria Dickons, with whom she also gave joint concerts (Fenner 216). Perhaps Catalani was simply being capricious and unpredictable, or perhaps she was less difficult than she was reputed to be.

Nevertheless, Catalani provided a convenient target for people who were dissatisfied with the state of opera in London. Gillen D’Arcy Wood has described the objections to Catalini of the middle-class, democratically minded, “Cockney” writers, who associated her imperiousness with the corrupt taste of a self-indulgent aristocracy.5 This anti-Catalani faction focused their energies on a long and arduous campaign to bring Mozart’s Don Giovanni to the stage of the King’s Theatre, an event that finally occurred in 1817, the year of Jane Austen’s death and after Catalani had left London for the continent. Like the other Mozart-Da Ponte collaborations, Don Giovanni requires a group of singers of equal talent, who each have their moments to shine but must also collaborate on complicated ensembles (Wood 136-38). Thus, Mozart’s operas were seen as the antithesis to Catalani’s star vehicles.

In fact, Le Nozze di Figaro and Così Fan Tutte had already been presented at the King’s Theatre, and Catalani had even bowed to pressure by appearing as Susanna in the former—characteristically appropriating the arias of other characters and adding her own vocal embellishments (Pleasants 113). The resounding success of Don Giovanni—twenty-six performances in 1817 alone (Fenner 294)—proved to the “Cockney” writers that a more “democratic” kind of opera was indeed the wave of the future.

“Bravuras, or Rival Syrens”: this satirical print incongruously

pairs Elizabeth Billington (l) with Angelica Catalani (r).

Hand-colored etching by Mat of the Mint, after Charles Williams (1807).

© Victoria and Albert Museum.

Diva rivalries in Emma

The characters in Emma cannot really be said to correspond exactly with any of these historical performers, but some parallels are evident. Although the three most prominent musical performers—Emma, Jane Fairfax, and Augusta Elton—are amateurs rather than professionals, the dynamics of their musical and social interactions mirror the relationships between the celebrated opera stars of the day in intriguing ways. As we have noted, music-making is not only an important component of social behavior; in this society, musical talent had a complicated relationship to social status. Just as the rivalries between professional prima donnas are ultimately based on comparisons between complementary talents and contrasting personalities, Emma offers several possible comparisons between its female characters as musicians, with indicators as to how their musical talents reflect their personalities.

At the beginning of the novel, Emma is the prima donna (first woman) of Highbury, without a serious musical or social rival until the arrival of Jane Fairfax. Emma is a talented musician who, despite good training and a considerable degree of leisure, has not reached her full potential. This state of affairs is of a piece with her lack of self-discipline and application in other areas. Mr. Knightley complains that “‘Emma has been meaning to read more ever since she was twelve years old,’” adding that she “‘will never submit to any thing requiring industry and patience’” (37). Her output in drawing amounts to a portfolio of unfinished portraits (44). In music and drawing, “steadiness had always been wanting. . . . She was not much deceived as to her own skill either as an artist or a musician, but she was not unwilling to have others deceived, or sorry to know her reputation for accomplishment often higher than it deserved” (44).

With her music, as with other accomplishments, an argument can be made that a lack of serious competition has allowed Emma to coast. Jane’s arrival allows for a direct comparison with Emma, the established star; like Francesca Cuzzoni and Elizabeth Billington, Emma must find a way to deal with the threat of a rival. The word “threat” might seem overstated, but it is clear that, in addition to her other accomplishments, Jane is highly talented both as a singer and as an instrumentalist, with a repertoire extending from Scottish and Irish songs to Italian arias—the latter sung, as we know from Harriet, in the original language.

That Emma is aware of her own deficiencies is made clear in her most important performance in the novel, at the party at the Coles’ in volume 2, chapter 8. Jane also performs at the party, thus allowing for a direct comparison. The reader never knows what kinds of pieces are performed, although the text clearly indicates that vocal selections are included: Emma “knew the limitations of her own powers too well to attempt more than she could perform with credit; she wanted neither taste nor spirit in the little things which are generally acceptable, and could accompany her own voice well” (227). Jane’s performance, by contrast, is of such fine quality that it causes Emma to attempt a corrective the following day: “She did unfeignedly and unequivocally regret the inferiority of her own playing and singing. She did most heartily grieve over the idleness of her childhood—and sat down and practised vigorously an hour and a half” (231).

Any attempt to dismiss this sudden burst of dedication as based solely on a desire to best her rival in the future is, however, undermined by Emma’s subsequent discussion with Harriet about the domestic concert at the Coles’. Far from reacting like a threatened diva, Emma must generously (and over Harriet’s loyal objections) acknowledge that Jane is her superior in talent, possessing both “‘taste’” and “‘execution’” (231-32). The apparent conflict between these aspects of musical performance reenacts the debate that had raged throughout the eighteenth century regarding the perceived superficiality of technical virtuosity (Wood 164-65).6 Emma is capable of realizing that technical ability does not preclude sincerity or depth of feeling. As Gillen D’Arcy Wood puts it, “The correctness of this judgment is born out at the conclusion of the book: [Jane Fairfax] is heartstricken, not heartless” (165). Far from being a conflict between two equally opposed talents, it appears that this particular musical rivalry is not much of a contest after all.

Attempts to relate the Emma-Jane rivalry to the historical diva rivalries we have examined reinforce this lack of a true contest. If Bordoni and Billington excelled at technical virtuosity and Cuzzoni and Grassini were celebrated for pathos, which is Emma, and which is Jane? If virtuosity equals “execution” and pathos equals “taste” (which can include sensibility), then the answer is clear: Jane Fairfax, as Emma herself puts it, “has them both” (232). In other words, Jane combines the best qualities of these divas as performers, while Emma seems to have the self-assurance of a prima donna without also possessing the high level of talent and hard work to justify it.

Jane Fairfax herself, though, is not entirely without the diva temperament. She is hardly a drama queen, but she is a sensitive person whose outward reserve belies her inner suffering. Although she lacks the cheerful charm of an Elizabeth Billington, she shares Billington’s use of music to cover what for most of the novel is an unhappy personal life. Jane’s emotional outbursts apparently tend to break out largely behind the scenes. The reader only really experiences a display of temperament from Jane at the Donwell strawberry picking party (362-63). For the most part, Jane suffers in relative silence, although it is possible that music allows her an outlet to express her inner feelings beyond the bounds of social convention.7

As we have seen, the rivalries of the professional stars were the source of a kind of appalled delight for newspaper readers and other lovers of gossip. It would be incorrect to say that the denizens of Highbury take a similar view of Emma’s “unjust” dislike of Jane Fairfax. On the contrary, the characters in Austen’s novel seem determined to promote a harmonious relationship between the two women. Mr. Knightley, in particular, is like the management of the King’s Theatre, promoting the harmonious duets of Billington and Grassini in Il Ratto di Proserpina. Yet, as Mary Ann O’Farrell argues, this longing for harmony is based on the same kinds of comparisons between relative talents and character traits that characterized discussion of the rivalries of professional singers. As O’Farrell puts it, the “supposition” of a harmonious relationship between Emma and Jane, to Emma’s chagrin, is “based upon an unpleasant principle of complementarity,” in this case between Emma’s openness and Jane’s reserve (49). Emma may be understandably annoyed at this tendency to comparison, but seen in a more positive light, this complementarity is an encouragement to wholeness and harmony.

In contrast to both Emma Woodhouse and Jane Fairfax, Augusta Elton’s musical talents are based on hearsay rather than direct experience. Their first exchange on the subject begins with Emma saying: “‘I do not ask whether you are musical, Mrs. Elton. Upon these occasions, a lady’s character generally precedes her; and Highbury has long known that you are a superior performer.’” Mrs. Elton demurs, calling her own playing “‘mediocre to the last degree’” (276). Whether this self-judgment is objectively truthful or based on false modesty is never proven, as it seems the other characters never actually hear Mrs. Elton perform.

Furthermore, despite Mrs. Elton’s professions of delight in finding herself in a “‘musical society’” and her proposal that she and Emma should form a “‘musical club’” (277), Emma soon comes to the conclusion that Mrs. Elton is “determined upon neglecting her music” (278). It is true that most women of the period found less time for music-making (and drawing and other polite accomplishments) after marriage, but, as Emma discerns, Mrs. Elton’s determination to neglect her music borders on an obsession. Mrs. Elton’s strategy seems clear: by not performing before the other residents of her new community, the true nature of her talent remains an unknown quantity, and thus that talent cannot be subjected to comparison and judgment. Rather than expose herself to comparison, Mrs. Elton can continue to coast on her reputation as musical without offering any proof.

Thus, Mrs. Elton is like a retired diva, whose own level of talent can never be accurately assessed, perhaps to her own relief. In this regard, she is akin to Austen’s social acquaintance the Comtesse d’Engtraigues. A detail that links Mrs. Elton to the stars of Italian opera is her use of an Italian phrase, caro sposo (278-79). It is tempting, if speculative, to see in this phrase a subtle nod to the stars of the Italian opera. Like Grassini and Catalani, Mrs. Elton is arguably a foreign interloper (from Bristol), who has entered the Highbury social scene with the apparent desire, to use Mount Edgcume’s phrase, to “kick down the ladder” and stand alone as the prima donna of Highbury.

The prima donna of Highbury

Catalani enshrined in an ornate frame.

Stipple engraving by Sidney Hall,

after William Henry Brooke (after 1817).

TCS_45 (Catalani)

Houghton Library, Harvard University. (Click on image to see a larger version.)

If Jane Fairfax is musically the combination of the best traits of several historical divas, and Mrs. Elton is the former diva coasting on her past reputation, who is Emma Woodhouse? In this case, there is a temptingly easy comparison: to Angelica Catalani, the dominant singer on the Italian opera scene during the period of Austen’s literary maturity. Although not apparently capable of Catalani’s musical virtuosity, Emma shares some of Catalani’s personality traits. Emma is accustomed to being the first woman of Highbury in the same way that Catalani enjoyed an apparently unassailable position as prima donna of the King’s Theatre from 1806 to 1814. Emma may be willing to admit that Jane’s musical talents are superior to her own, but she does not particularly like to share the social limelight with anyone else. Just as Catalani preferred to perform music by lesser talents who could serve her star power, Emma is much happier in situations in which her intellectual abilities and social supremacy are taken for granted. She does not take challenges to her hegemony particularly well, either from the non-threatening Mrs. Cole or from the upstart Mrs. Elton. Yet, just as Catalani could share the stage with Maria Dickons and was celebrated for her acts of charity, Emma can be considerate and generous in sometimes unexpected ways. As noted, she can generously acknowledge Jane Farifax’s superior musical talent, and she seems to take her role as charitable lady seriously, in regard to the Bateses (for the most part) and to those even less fortunate in the community.

In fact, Emma is ultimately capable of rising above herself in ways that make her quite unlike a stereotypical diva. An argument could be made that her development mirrors or parallels the story of producing Italian opera in London during the 1810s. At the beginning of that decade, the King’s Theatre was dominated by Angelica Catalani, an undeniably great singer who nevertheless felt threatened by challenges to her supremacy and refused to change, continuing to perform star vehicles designed to show off her impressive technique. Only a few years later, the success of Mozart’s operas set a new standard for artistic excellence based on the efforts of an ensemble. Emma Woodhouse, by contrast, may begin the novel believing herself to be the prima donna of Highbury, a star surrounded (in a way) by puppets. Over the course of the novel she has to learn how to be part of an ensemble, that is, a community. She must be made to realize that the “small band of true friends” (484) comprises her colleagues and not merely her audience. Truly great artists know that they cannot do it alone, and that even the greatest star shines most brightly when surrounded by “superior performer[s]” (276) at every level. It is a difficult lesson for Emma to learn, but it is this process that makes her, if not exactly a goddess, then certainly a better human being.

NOTES

1We are indebted to Claire Bellanti’s ongoing research in this area. See also Erickson.

2Lenneberg outlines the usual details in “Early Circulating Libraries and the Dissemination of Music” (125).

3These books (CHWJA/19/2 and CHWJA/19/3) in Austen’s own hand are available as part of The Austen Family Music Books collection at the University of Southampton’s internet archive: https://archive.org/details/austenfamilymusicbooks

4In any case, the “Rival Queens” continued to share the stage even after the 1727 incident. It is generally accepted that the humorous conflict between Lucy Lockit and Polly Peachum in The Beggar’s Opera by John Gay and Johann Christoph Pepusch (first performed in 1728 and still a staple of English language opera in Austen’s time) are intended to parody the Cuzzoni-Bordoni rivalry (Hume).

5The Cockney writers, so-called because of their preference for the unpretentious and the vernacular, included figures who are not well remembered today, such as Leigh Hunt, Charles Lamb, Thomas Alsager, and Vincent Novello, but their circle extended to John Keats and Percy Bysshe and Mary Shelley (also enthusiastic admirers of Mozart). As Alsager put it, “The distinctions of prima donna and primo uomo should absolutely merge in the general excellence of the whole corps. With the sublime composer of Don Giovanni, . . . whether we choose to bestow on the orchestra, or the singers, our exclusive attention, we may imbibe a distinct perception of beauty” (qtd. in Wood 137).

6Wood is specifically discussing Jane Fairfax’s pianism, but the possibility that the same qualities apply to her singing cannot be ruled out.

7In the 1996 Meridien/ITV/A&E version of Emma, the Italian selection performed by Jane Fairfax is a setting by Gioachino Rossini of Pietro Metastasio’s text “Mi lagnerò tacendo.” The original text, an aria from Metastasio’s opera libretto Siroe (1727), was set by Rossini many times, and the version used in the film was in fact not published until 1857. Despite the obvious anachronism, the choice is dramatically appropriate for Jane Fairfax since the first line of the text can be literally translated as “I languish in silence.”