|

Persuasions #12, 1990 Pages 88-98

Dining at the Great House: Food and Drink in the Time of Jane Austen EILEEN SUTHERLAND North Vancouver, BC What did they have for dinner? Jane Austen gives us few details. Elizabeth Bennet and the Collins are invited to dine at Rosings with Lady Catherine: what did they eat? Not a word from Austen on that subject, except that Mr. Collins carved, and ate, and praised every dish on the table. Fanny Price and Edmund dined at the parsonage in Mansfield Park, an important occasion in Fanny’s social life – but what did Mrs. Grant serve? We had been told earlier there would be a turkey – otherwise, not a clue! Austen was writing for her contemporaries, and they all knew just what sort of a meal would have been provided on each occasion, so why should she elaborate? Eighteenth century England was in a state of transition, and one of the changes was in the houses themselves. Earlier in the century, the upper class homes consisted of a multi-purpose Great Hall, surrounded by a number of formal “apartments” opening into each other, decorated with rich, patterned fabrics, marble and stucco, gilding and tapestry. By Austen’s time, however, ideas of comfort and privacy were becoming common; rooms, opening off a corridor, were described as “pretty” or “smart,” and a new taste for intimacy and informality was prevalent. Instead of the multi-purpose hall, rooms were being used for specific purposes: there was a billiard room, a music room, a library – but the idea of a special room for eating was still uncertain as late as the mid-1700s. If there was a dining room, it was most often

used only for formal dinners; the family usually had their meals in a

“breakfast parlour” or “morning room,” or even in the library. Most paintings of interiors of this period

show the rooms empty in the centre, with the furniture arranged around the

walls, to be brought forward by servants when required. The old-fashioned parlour in the Great House

at Uppercross was being modernized by the Musgrove daughters, with “little

tables placed in every direction” (P, 40). The dining tables were often made as “sets,” of several tables of

different sizes, which could be brought together for special occasions, and

between meals the tables and chairs were placed back along the walls. In Edinburgh, the Georgian House, designed by

Robert Adam, has been opened to the public, furnished as it might have been

when it was first occupied as a town house in 1796. In the dining room the table is made up of a rectangular gate-leg

table and two half-circles, which together form a large oval table covered with

a single cloth. Some country houses

used either of two tables, one large and one small, according to the number of

diners. This custom of different-sized

tables and folding tables that could be moved around at will, lasted until near

the end of the 18th century. People

still preferred dining in small groups: Mr. Woodhouse “considered eight persons

at dinner together as the utmost that his nerves could bear” (E, 292). The single large table was just becoming

fashionable at the turn of the century.

In Emma, the company take their places round

the large modern circular table which Emma had introduced at Hartfield, and

which none but Emma could have had power to place there and persuade her father

to use, instead of the small-sized Pembroke on which two of his daily meals

had, for forty years, been crowded. (E,

347) At Mansfield Park, Mrs. Norris complains, as

usual about the Grants, who have succeeded to her place at the Parsonage: [There

will be five at dinner] and round their enormous great wide table, too, which

fills up the room so dreadfully! Had

the Doctor been contented to take my dining table when I came away, as any body

in their senses would have done, instead of having that absurd new one of his

own, which is wider, literally wider than the dinner table here! (MP, 220) Except in circles very conscious of rank, there was no formal “taking in” of the ladies by the gentlemen. The host would escort the most important lady, and the other guests would follow in a body. In earlier years, the gentlemen all sat on one side of the table, the ladies on the other. When it became customary to sit alternately, this was called “dining promiscuously”! The numbers of ladies and gentlemen did not need to be equal, and guests usually sat wherever they liked. At dinner at the Coles’ house, Emma found Frank Churchill seated

by her – and, as she firmly believed, not without some dexterity on his

side. (E, 214) In Pride and Prejudice, Bingley, formerly courting Jane, has

returned after a long absence. When they repaired to the dining-room, Elizabeth eagerly watched to see whether Bingley would take the place, which, in all their former parties, had belonged to him, by her sister. Her prudent mother, occupied by the same ideas, forbore to invite him to sit by herself. On entering the room, he seemed to hesitate; but Jane happened to look round, and happened to smile: it was decided. He placed himself by her. (340) The hostess sat at the top of the table, the

host at the foot. Dining at Rosings,

Mr. Collins “took his seat at the bottom of the table, by her ladyship’s

desire, and looked as if he felt that life could furnish nothing greater” (P&P,

162). Married ladies sometimes took precedence over

unmarried ones, and a new bride was singled out for special treatment. In Pride and Prejudice, the youngest

daughter Lydia comes home after her scandalous elopement and subsequent

marriage. Elizabeth joins the family at

dinner time soon enough to see Lydia, with anxious parade, walk up to her mother’s right hand, and hear her say to her eldest sister, ‘Ah! Jane, I take your place now, and you must go lower, because I am a married woman.’ (317) Another who insisted on all her rights and privileges was Mrs. Elton, the newly-married, nouveau-riche social climber from trade circles in Bristol. Dinner

was on table. – Mrs. Elton, before she

could be spoken to, was ready; and before Mr. Woodhouse had reached her with

his request to be allowed to hand her into the dining-parlour, was saying –

‘Must I go first? I really am ashamed

of always leading the way.’ (E,

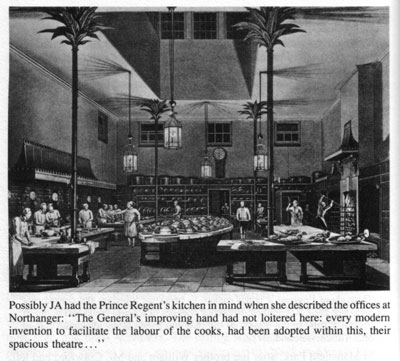

298) Kitchens, also, were changing and being modernized at this period. Cooking had formerly been done over the open fire in the great fireplaces, with racks to hang pots and kettles, and spits to roast meats. At Saltram, in Devon, the kitchen of the Great House was rebuilt after a fire in 1779. It is probably typical of kitchens in Great Houses of that period. A small room at one end is a butchery, fitted

with racks for hanging carcasses, massive chopping blocks, cutting tables and

scales. At the other end is the

scullery, with a large lidded copper tank for steeping meats or vegetables, and

two pairs of double sinks, for washing up. In the kitchen itself is a great open range,

heated by coal and fitted with a water tank with taps for hot water. The draft created by the heat from the fire

drives a fan set in the chimney and connected to gears, pulleys and chains,

which turn the spit for roasting. The

width of the fire can be adjusted by moving the sides, called “winding cheeks,”

in or out. Across one end of the

kitchen are shelves on which are ranged the batterie de cuisine, the

copper pans and molds (in the case of Saltram, over 600 pieces) which were

necessary for preparing the enormous meals; and on a dresser, the china for

serving them. There is the usual full

complement of iron kettles and pots, pewter plates and earthenware and wooden

vessels. On tables and in odd corners are spice boxes, cannisters for tea and coffee, vinegar barrels, mincing and grinding machines, pestles and mortars, vast milk jugs, and brass skimmers. The ceiling was well stored with hanging provisions of various kinds, such as sugar loaves, black puddings, hams, sausages, and flitches of bacon. A baking oven was separately fired – usually by

building the fire inside the oven itself until it was hot enough, then raking

out the ashes, sweeping it clean, and putting in the bread to be baked. When the bread was finished, a second

baking, at a lower temperature, could be done with the reserved heat. Most ordinary homes did not have their own

baking ovens. The local baker would

usually agree – perhaps for a small fee – to bake the neighbours’ dinners after

his bread baking was done. In the midst

of a long monologue, Miss Bates, in Emma, mentions, “Then the baked

apples came home; Mrs. Wallis sent them by her boy.” (236) In Cranford, just a little later than

Austen’s day, the ladies discussed the circumstances of the Captain taking a poor old woman’s dinner out of her hands one very slippery Sunday. He had met her returning from the bakehouse as he came from church, and noticed her precarious footing … and he relieved her of her burden, and steered along the street by her side, carrying her baked mutton and potatoes safely home. (Gaskell, 20) Another change in Austen’s lifetime was the

times of meals. Breakfast was not

early. Some great ladies had trays

brought up to their rooms and remained in bed until noon. Most households, however, assembled in the

“breakfast room.” The usual hour was 9

or 10. It was often the custom to be up

and doing something for several hours before breakfast. In Sense and Sensibility, Edward

Ferrars walked to the village to see to his horses before breakfast (p. 96);

Georgiana Darcy travelled to Pemberley arriving “only to a late breakfast,”

although we don’t know where she had come from (P&P, 266). In Emma, John Knightley and his

little boys go for a walk before breakfast and meet Jane Fairfax, on her way to

fetch the letters from the Post Office (p. 293). And in Persuasion, Anne Elliot and Henrietta have a stroll

along the beach at Lyme, a long talk, meet Louisa and Captain Wentworth, and

walk in to town to shop, “loitering about a little longer,” all before

breakfast was ready (p. 104). Jane Austen herself, in London, wrote to her sister: Thursday

morning, half-past seven. – Up

and dressed and downstairs in order to finish my letter in time for the

parcel. At eight I have an appointment

with Madame B. [Henry’s housekeeper], who wants to show me something

downstairs. At nine we are to set off

for Grafton House, and get that over before breakfast. (Letter 82, 322-23) In a later letter, she mentions that at Grafton House, the drapers, she bought material for a gown for her sister and also some worsteds, which she hopes will be approved of as “I had not much time for deliberation” (Letter 83, 326). I don’t know how far she had to travel to the shops and back, but she certainly accomplished a lot before breakfast! A Frenchman, visiting England at this time,

wrote Throughout England it is the custom to breakfast together; the commonest breakfast-hour is 9 o’clock. Breakfast consists of tea and bread and butter in various forms. In the houses of the rich you have coffee, chocolate and so on. (Rochefoucauld, 21) At Mansfield Park, after her brother William

and Mr. Crawford had left, Fanny walked back to the breakfast-room where she

looked sadly at the “remaining cold pork bones and mustard in William’s plate”

and the “broken egg-shells in Mr. Crawford’s” (MP, 282) – a more

substantial breakfast than tea and toast. The “morning” was all the rest of the day

before dinner – usually all the daylight hours; the word “afternoon” was seldom

used. There was no formal regular meal

between breakfast and dinner. Something

to eat at midday was gradually becoming more common, as the dinner hour grew

later. In the novels, a noon meal is

named only twice: in Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth and Jane on their

way home from London are met at an inn by Lydia and Kitty, who plan “the nicest

cold luncheon in the world” (222) and which, incidentally, Elizabeth and Jane

had to pay for; and in Sense and Sensibility, Willoughby, rushing to see

Marianne who is very ill, stops only for a “nuncheon” of cold beef and a pint

of porter. Travellers often had to stop

and rest their horses, and inns usually served cold meals at this time of day. Although a table was not formally laid at

mid-day in the dining-room, a fairly substantial meal was usually eaten

informally. At Pemberley, the ladies

are served “cold meat, cake, and a variety of all the finest fruits in season …

beautiful pyramids of grapes, nectarines and peaches” (P&P,

268). Picnics are planned for mid-day,

in Sense and Sensibility with “cold ham and chicken” (32), and in Emma,

with “pigeon-pies and cold lamb” (353).

At Mansfield Parsonage, Dr. Grant does the “honours” of the sandwich

tray (MP, 65) and at Uppercross, at Christmas, tables and trestles groan

under “the weight of brawn and cold pies” (P, 134). Another meal that varied considerably according to the time and place, was the evening meal called “supper.” The main meal of the day was called “dinner,” and if it was early, a light supper would be served in the evening. Among the wealthy and fashionable, dinner was served late, and supper was dispensed with, except at parties and balls. In less pretentious homes, supper was served informally, often in the room where the family was sitting for the evening. Many letters mention that no servants were waiting at supper.

Mr. Woodhouse “loved to have the cloth laid,

because it had been the fashion of his youth” (E, 24), and meal included

minced chicken, scalloped oysters, boiled eggs, apple tart and custard, as well

as the basin of gruel which was all he wanted.

Mrs. Bennet served suppers, perhaps, as Austen herself wrote in a

letter, “the remains of her old Meryton habits” (Letter 77, 300). Supper at Mansfield Park was served in the

drawing room, from a tray, where Edmund found a glass of Madeira for Fanny (MP,

74). In The Watsons, the

distinction between dinner and supper is made quite clear: the snobbish

social-climbing Mrs. Robert Watson declares “We never eat suppers” (W,

351), and the equally snobbish and socially-conscious Tom Musgrave leaves the

Watsons’ house at the first sign of the supper-tray, because he intends his

next meal to be a dinner at his inn (W, 359). Dinner was the grand meal of the day. Generally speaking, the hour of dinner got

later and later during the 18th century.

The time varied with the degree of fashion and status of the diners. At Barton Cottage and at Hartfield, it was 4

o’clock (S&S, 361, E, 81); at Mansfield Park it was 4:30 (MP,

221). Mrs. Jennings, in London, dined

at 5 (S&S, 160); General Tilney, even in the country, also dined precisely

at 5 (NA, 162). The Bingleys,

people “of decided fashion,” dined at 6:30 (P&P, 10, 35). In the shooting season, dinner tended to be

later, and in the country it was usually earlier than in London. Service à la Russe – where

servants passed each dish to the guests to help themselves, the usual manner in

Europe – was just beginning to be fashionable in England in the early 19th

century. More commonly, dinner was

served in courses, but the word “course” did not mean what it does today. All the dishes of food were placed on the table

in a precise, formal, symmetrical fashion: certain ones at the top and the

bottom of the table, others in the middle, the corners, or the sides. Cook-books often specified where a certain

dish should be placed; perhaps a top dish for a second course would be

considered a side dish for a first course.

When some of the dishes of food had been finished, servants sometimes

exchanged them for others – these were called “removes”: a brown soup might be

“removed [i.e. replaced] with fish”; a “rump with greens” removed with a

roasted turkey. When the diners had

eaten all they wished, the dishes would be taken away; even the tablecloth was

usually removed and replaced with a new one, and the table was covered again

with more dishes of food. Each of these

complete layings of the table was called a “course.” A family meal might be only one course. In The Watsons, Elizabeth Watson leads the family,

including the visiting brother and sister-in-law, to the table and announces,

“You see your dinner” (354), meaning that there will be no second course to

follow. There was a roasted turkey

brought in later (a “remove”), but that didn’t count as another course. In Pride and Prejudice, Mrs. Bennet was

determined to impress Bingley and Darcy.

She had been strongly inclined to ask them to stay and

dine there that day; but, though she always kept a very good table, she did not

think any thing less than two courses, could be good enough for a man, on whom

she had such anxious designs, or satisfy the appetite and pride of one who had

ten thousand a-year. (338) At the famous dinner at the Coles’, Emma and Frank Churchill were called

on to share in the awkwardness of a rather long interval between the courses,

and obliged to be as formal and as orderly as the others; but when the table

was again safely covered, when every corner dish was placed exactly right, and

occupation and ease were generally restored

(E, 218) they could carry on their private conversation. We read of enormous banquets of this period,

with literally almost a hundred separate dishes (“Dr. Grant had brought on

apoplexy and death, by three great institutionary dinners in one week”) (MP,

469), but usually a diner only ate a little of several dishes – much like a

smorgasbord today. Each person was

supposed to carve or serve the dish that was immediately in front of him, but

this did not always work out very well.

The near neighbours on each side could pass a plate and ask for a

serving, but others farther down the table wouldn’t receive any of that

particular dish. In one of her letters,

Jane Austen mentions a friend at dinner: She placed herself on one

side of [Mr. P.] … & she had an empty plate, & even asked him

to give her some mutton twice without being attended to for some time. (Letter 75, 293) Two courses was an average dinner, with from five dishes a course for a simple family meal, to as many as twenty-five for a grand entertainment. Both sweets and savouries came with each course, but the first course was usually slightly heavier. Then the table was cleared again, even the tablecloth taken away, and the dessert and wines were brought in. Things like custards, blanc mange, molded jellies, and fruit pies, were part of the earlier courses. Dessert was simpler – fruit, raisins and nuts were commonly served. The ladies usually drank one glass of wine, and

then left the table all together and returned to the drawing-room. There, they entertained themselves in

whatever way they wished until the gentlemen joined them. At Netherfield, when Jane was ill, “with a

renewal of tenderness” the Bingley sisters “repaired to her room on leaving the

dining-parlour, and sat with her till summoned to coffee” (P&P, 37). When Darcy and Bingley had returned to

Longbourn, but the future was still uncertain, “the period which passed in the

drawing-room before the gentlemen came was wearisome and dull to a degree that

almost made Elizabeth uncivil” (P&P, 341). At Rosings, it was merely dull: “there was little to be done but

to hear Lady Catherine talk, which she did without any intermission till coffee

came in” (P&P, 163). Meanwhile, the gentlemen remained at the table

drinking. Heavy drinking after dinner

was not universal, of course, but it was a hard-drinking age, and obviously was

common. Much would depend on the host

and hostess, and what they expected of their guests. Sometimes the men left the dining-room in a body: the host’s

“Shall we join the ladies?” would get everyone up and moving. On other occasions, the men left one or two

at a time, as they pleased. Where there

were marriageable young ladies and eligible young men in question, no hostess would

keep them long apart.

“I

have found you out in spite of all your tricks.” (S&S) Old cook-books of the period, like The

Experienced English Housekeeper of 1782, give an interesting view of

English “cookery” – recipes call for condiments, sauces and spices galore; wine

is used in almost every meat dish; butter and cream are used lavishly; and the

variety of fruits and vegetables that were available to the cook of the time is

amazing: all the common ones we have today, as well as finocha, borecole,

cardoon, coleworts, rocambole, bugloss and skirret,

for example (Raffald, 172-83). Anchovies were often used as a substitute for salt in flavouring sauces. Other common seasonings were black, white and Jamaica peppers (the last is allspice), mace, sage, parsley, garlic, shallots, juniper berries, scraped horseradish, capers, savory, pickled mushrooms or mushroom powder, morels and truffles. This doesn’t sound like the notorious bland English cooking we hear of. Cooks distinguished between loaf sugar, double or triple refined, brown and powder sugar. They used Rhenish wine, Lisbon wine (which may be port), Madeira, Claret, Champagne and French brandy. Recipes are given for home-made wines, brandies, beers and mead. In one of Jane Austen’s letters, she mentions

being given “a Hare and 4 Rabbits” and thus they were “well stocked for nearly

a week” (Letter 117, 437). Among meats,

mutton was the most common. Its

popularity resulted in the expression which Jane Austen uses several times in the

novels for a casual dinner invitation: “Come and eat your mutton with us” (NA,

209; MP, 215, 406). Mr. Watson, like Mr. Woodhouse, likes to have a basin of gruel before retiring to bed. Poor old dears, one pities them as victims of indigestion and insomnia. At least, I used to think of them like that until I came across recipes for gruel, which gave me second thoughts about these two elderly gentlemen. Most gruels in old cook-books – made from groats, sago or barley – call for almost as much wine as water, and are flavoured with sugar and cinnamon or nutmeg. One would certainly sleep like a baby after a bowlful. White soup seems to have been served

continuously all evening at a ball – it had to be made before the Netherfield

ball (P&P, 55), Emma Watson enjoyed it at the Edwards’ after their

ball (W, 336), and Fanny Price had it at the ball in her own home at

Mansfield (MP, 280). It was made

by stewing together veal, fowl, bacon, rice and herbs, and adding ground

almonds, cream and eggs. It should be

very relaxing for young ladies who had “danced every dance.” Mrs. Bennet, expecting a guest for dinner,

lamented “how unlucky there is not a bit of fish to be got today” (P&P,

61). The “fysshe days” ordained by the

Mediaeval Church amounted to as many as 166 a year. Even with more relaxed conditions in the 18th and 19th centuries,

on Fridays and all forty days of Lent at least, meat was not served. Larger estates had their own well-stocked

fish ponds, or good fishing streams.

But there was plenty of variety to substitute for meat besides fish –

eels, lampreys, oysters, shrimp and lobster, cockles and mussels, were all

common foods, and relatively inexpensive. Potatoes were just becoming popular in the late 18th century – it took real famine conditions for them to be totally accepted. Gilbert White wrote, in 1778 Potatoes have prevailed in this little district … within these twenty years only; and are much esteemed here now by the poor, who would scarce have ventured to taste them in the last reign. (201) Mrs. Austen herself, at Steventon, grew potatoes in her garden, and

tried to get the villagers to grow them, but they refused. Kitty and Lydia Bennet were employed “dressing

a sallad and cucumber” while they waited for their sisters (P&P,

219). We don’t know what was in their

“sallad.” It may have included

tomatoes, which were becoming a popular food at this time. Early 19th century cook-books give recipes

for "tomata ketchup” and “pies made of tomatus,” and sliced raw tomatoes

were gradually finding favour, instead of being thought poisonous as they were

at first in Europe. Cucumbers, on the

other hand, were well known in England since the 14th century, although not

always appreciated. Dr. Samuel Johnson

said, “cucumber should be well sliced, and dressed with pepper and vinegar, and

then thrown out, as good for nothing” (Root, 99). The early cook-books give a good indication of the wide range of imported foodstuffs as well as the variety of locally-grown products in England at the time. Besides the lavish use of ingredients, the time and labour required for some of the recipes seem incredible. Many of the directions include “beat for half an hour” or “whisk it an hour.” A cake recipe calls for “an hour and a half of beating” and a preserve needed to be boiled an hour and a half stirring all the time. Well beaten eggs were required in the days before baking-powder, and cheap labour was abundant: even the Bates had a maid, and the Watsons and the Prices had two. Halfway around the world, at a similar time, the artist Paul Kane described a Christmas feast at a fur-trading post in the Northwest. Everything was kept as much as possible “just like home” [This

was] the fare set before us, to appease appetites nourished by constant outdoor

exercise in an atmosphere of 40-50° below zero. At the head, before Mr. Harriett, was a large dish of boiled

buffalo hump; at the foot smoked a boiled buffalo calf … My pleasing duty was to help a dish of

mouffle, or dried moose nose; the gentleman on my left distributed, with

graceful impartiality, the white fish, delicately browned in buffalo

marrow. The worthy priest helped the

buffalo tongue, whilst Mr. Rundell cut up the beavers’ tails. Nor was the other gentleman left unemployed,

as all his spare time was occupied in dissecting a roast wild goose. The centre of the table was graced with

piles of potatoes, turnips, and bread conveniently placed, so that each could

help himself without interrupting the labours of his companions. Such was our jolly Christmas dinner at

Edmonton; and long will it remain in my memory, although no pies, or puddings,

or blanc manges, shed their fragrance over the scene. (103) WORKS CITED All references to Jane Austen’s works are to The

Novels of Jane Austen, ed. R.W. Chapman, 3rd ed. (London: Oxford University

Press, 1934); Minor Works (The Watsons) (1954): and Jane Austen’s

letters to her Sister Cassandra and Others, ed. R.W. Chapman (London:

Oxford University Press, 1952). Gaskell, Mrs. Elizabeth. Cranford (London: Macmillan, 1922). Kane, Paul.

“Christmas at Fort Edmonton,” Beaver, December 1927. Raffald, Elizabeth W. The Experienced English Housekeeper (London: R. Baldwin,

1782). Rochefoucauld, François de la. A Frenchman’s Year in Suffolk.

Trans. Norman Scarfe (London: Boydell Press, 1988). Root, Waverley. Food (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1980). White, Gilbert. The Natural History of Selborne (Harmondsworth, Middlesex,

Penguin Books Ltd., 1977. |