|

Persuasions #7, 1985 Pages 78-81

Blaise Castle

MAGGIE LANE

Blaise Castle on the northwestern outskirts of Bristol has one direct and several indirect links with Jane Austen. Its name has been made famous by Northanger Abbey (though incorrectly spelt therein with a z) and its history provides a fascinating insight into the cult of the Picturesque, which impinges on all Jane Austen’s novels.

The Blaise estate adjoins the downs of Kingsweston, where, (how can we forget?) the Sucklings have twice ventured in their barouche-landau. The Sucklings lived “near Bristol,” and to drive to Kingsweston was not unreasonable; but Isabella Thorpe makes it her goal from Bath. Since Kingsweston and Blaise are quite on the other side of Bristol from Bath – a good twenty miles away altogether – she deludes herself about the possibility of getting so far and back in one day, especially in February, and in a pair of gigs with one horse apiece. James Morland, despite his infatuation for Isabella, expresses his doubts.

“You croaking fellow!” cried Thorpe, “we shall be able to do ten times more. Kingsweston! aye, and Blaize Castle too, and anything else we can hear of; but here is your sister says she will not go.”

He has unwittingly pronounced the one word which can tempt Catherine.

“Blaize Castle!” cried Catherine; “what is that?” “The finest place in England – worth going fifty miles at any time to see.” “What, is it really a castle, an old castle?” “The oldest in the kingdom.” “But is it like what one reads of?” “Exactly – the very same.” “But now really – are there towers and long galleries?” “By dozens.” (p. 85)

Doubly despicable Thorpe! For once he has Catherine’s whole-hearted attention, but though he does not scruple to violate the truth, he possesses so little imagination that he can only assent to the delights she herself dreams up. Tricked into setting off with him, Catherine “meditated, by turns, on broken promises and broken arches, phaetons and false hangings, Tilneys and trap-doors.” When she discovers Thorpe’s trickery,

Blaize Castle remained her only comfort; towards that, she still looked at intervals with pleasure; though rather than be disappointed of the promised walk, and especially rather than be thought ill of by the Tilneys, she would willingly have given up all the happiness which its walls could supply – the happiness of a progress through a long suite of lofty rooms, exhibiting the remains of magnificent furniture, though now for many years deserted – the happiness of being stopped in their way along narrow, winding vaults, by a low, grated door; or even of having their lamp, their only lamp, extinguished by a sudden gust of wind, and of being left in total darkness. (p. 88)

The four young people have set off far too late in the day, however, and after an hour, having got only halfway to Bristol, they are obliged to turn back. A second attempt is made a few days later, without Catherine. They start at eight in the morning and reach Bristol, but not Blaise; even so they come home in the dusk. Isabella and James have been so well occupied in becoming engaged that “Blaize Castle had never been thought of.”

Blaise Castle thus plays its part in forwarding the plot of Northanger Abbey and illustrating the characters of the Thorpes and Morlands, without Catherine ever seeing it. Jane Austen could not let her do so, for her disillusionment would have forestalled that which she is to experience at Northanger Abbey itself. The reality of Blaise remains a private joke between Jane Austen and her readers in the know. Catherine never discovers that far from being “the oldest in the kingdom,” Blaise Castle is in fact a mere eighteenth-century folly. It was famous enough in its time for Jane Austen to depend on her readers relishing Catherine’s ignorance. Today, perhaps, for a greater enjoyment of the novel, the history of Blaise requires to be told.

In 1762 Thomas Farr, a Bristol merchant whose fortune came from the transatlantic sugar trade, purchased the estate of Blaise, consisting of 400 acres of mainly hilly, wooded ground, and a rather modest house standing on the very edge of the property, as close as it could well be to the parish church and small village of Henbury. To the side of the house was a formal garden, whilst behind it the land rose steeply to reach the highest spot on the estate within a few hundred yards.

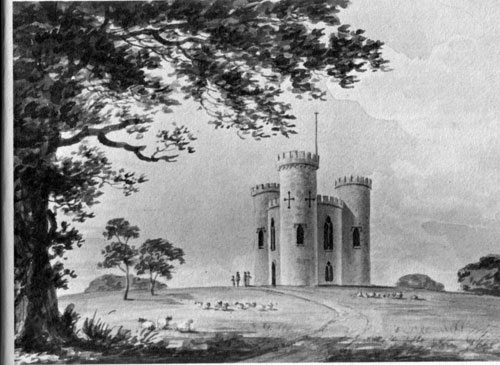

Blaise Castle, a watercolour by Humphry Repton from his Red Book for Blaise,1796.

“Smith’s place is the admiration of all the country: and it was a mere nothing before Repton took it in hand. I think I shall have Repton.” Mr. Rushworth, Mansfield Park.

This hilltop had been the site successively of an Iron Age fort, a Roman temple and a medieval church dedicated to St. Blaise (the patron saint of wool-combers), the last ruins of which had been removed in 1707. It was possibly regret for this act of insensibility which inspired Farr, in 1766, four years after taking possession of his estate, to build a “castle” on the very same spot.

He paid Robert Mylne £3,000 to design and build a folly that was habitable, as he wanted to use it as a retreat for meditation, as well as a vantage point from which to survey the Avon and Severn valleys, and a picturesque object to be glimpsed amid the trees from the windows of his house. The design features three ornate castellated turrets, one of which contains the staircase giving access to the flat roof of the central, lower tower. Traceried windows and cruciform arrow-slits supply the Gothic ornamentation, while stained glass and elegant interior plasterwork supplied the comfort. There was a vestibule and dining room below, and a main chamber above. Altogether a far cry from the castle of Catherine Morland’s imagination!

Thomas Farr went bankrupt in 1778 as a result of the American War of Independence, and was obliged to sell Blaise. Under the new owner, Denham Skeate, the retreat for meditation became open to the public, who flocked to enjoy the views. One famous visitor was JohnWesley, who in 1788 set out at six one morning from Bristol expressly to see the castle, recording in his diary, “Mr. Farr, a person of exquisite taste, built it some years ago on the top of a hill which commands a prospect all four ways nothing in England excells.” Praise indeed from such a well-travelled man. Perhaps Catherine would not have been disappointed, had she been able to visit it with the Tilneys to point out what was and was not picturesque about the view!

The property changed hands again in 1789 when it was bought for £11,000 by John Scandrett Harford, a Quaker banker and father of a large young family. In him Blaise found a fitting owner, whose greatest delight was the current passion for “improvements.” Until his death in 1815 he played happily with his estate, sparing no expense and employing the most famous names to advise him.

His first step was to pull down the old house and build the present Blaise Castle House nearby. Work was begun in October 1795 and by the following October the roof was on, in celebration of which seventy workmen were treated to a dinner, with a gallon of ale each, at the local inn. Designed by William Patey in the classic Georgian style, the main house is solid and sober, catching none of the Gothic fancifulness of its small neighbour. Over the years, offices, stables and an orangery were added, the last, which imparts some delicacy to the house, the work of no less an architect than John Nash. A pretty thatched dairy was his invention to fill the spot where the original house had stood.

Meanwhile Harford turned his attention to the grounds, and called in the leading landscape gardener of the period, Humphry Repton – whose terms, Mr. Rushworth assures us, were five guineas a day (though that was later). Repton visited Blaise four times during 1796-97, producing a detailed written account, illustrated by watercolour sketches, of the alterations he advised. In this “Red Book,” as he called it, he speaks of “the Genius of the place” and describes Blaise Castle as “embosom’d high in tufted trees.” His major contribution was the construction of a dramatic carriage drive between the house and a point on the furthermost perimeter of the estate, where a new Gothic gateway was provided. As much of the estate is hidden from the house, this was a good way of opening it up for enjoyment, and the road, which plunges up and down wooded ravines, must have thrilled such visitors as the Sucklings. It also counteracted the main drawback of the place, the proximity of the house to the village, by affording a much more imposing approach. As Repton wrote, “It may perhaps be urged that I have made a road where nature never intended the foot of man to tread … but where a man resides, nature must be conquered by art, and it is only the ostentation of her triumph, and not her victory, that ought ever to offend the correct eye of taste.”

Repton abolished the old formal garden (though a delightful small walled garden remains between the house and the dairy) and ordered the felling of seven sixty-foot elms from an old triple avenue. How Fanny Price would have mourned!

In 1812 Repton’s son George collaborated with Nash to design Blaise Hamlet, which consists of ten highly picturesque cottages, with twisted chimneys, low eaves and diamond-paned windows, grouped irregularly about a village green. Inevitably according to the ideas of the time, the £231 that they cost in total was devoted more to making a charming scene for the passer-by than to rendering the interiors comfortable and convenient for the inhabitants. Nevertheless there was humanity as well as vanity in the venture, as Harford intended the cottages to be “retreats for aged persons who had moved in respectable walks of life but had fallen under misfortunes, preserving little or nothing in the shock of adversity but unblemished character.”

Blaise Hamlet, exquisitely preserved and still inhabited, is now owned by the National Trust; the remainder of the Blaise estate is administered as a public amenity by Bristol City Council, which has created a Museum of Rural Life in the house itself. Blaise Castle, after falling into disrepair, has now, with the help of the Friends of Blaise, been made safe, and it is hoped ultimately to refurbish the interior. Meanwhile the staircase once again takes visitors to the roof to enjoy the view, which reaches beyond the modern sprawl of Bristol to the Welsh hills.

For those planning a Jane Austen pilgrimage to include Bath, it is worth sparing a day to visit Blaise. The drive can now be accomplished in less than an hour, so you are likely to be more successful than the Thorpes and Morlands! From Bath take the A4 west through Bristol and towards Avonmouth. About two miles after passing under Brunel’s famous Clifton Suspension Bridge, turn right at traffic lights (signposted Westbury-on-Trym), straight across at the next lights, left at the next and left at the next again (signposted Blaise).

|