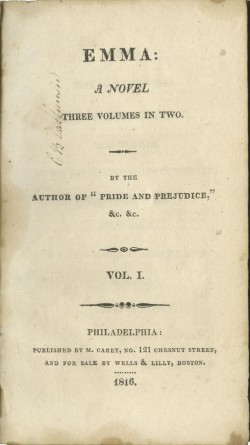

At the 2016 AGM, I presented new discoveries regarding the origins of the reprinted, two-volume 1816 Philadelphia Emma, the only edition of an Austen novel published in the U.S. during the author’s lifetime (“1816 Philadelphia Emma”). I shared too some of the stories that emerge from the very few surviving copies of this edition—just six, of which two were not previously known to Austen scholars. Each one is a unique physical artifact.

Title page of 1816 Philadelphia Emma showing “C B Dalhousie” signature. Courtesy Goucher College Special Collections & Archives

Some copies contain annotations that shed light on the responses of Austen’s early American readers, about which very little has hitherto been known. Other copies bear only evidence identifying their owners. Among the latter group is the beautifully bound copy now owned by Goucher College in Baltimore, Maryland, where I teach. Running vertically up each volume’s title page, just nudging the printed line “three volumes in two,” is the signature “C B Dalhousie.” Pasted on the inside front cover of each volume is a small, rectangular bookplate that reads “COUNTESS OF DALHOUSIE.”

Who was the Countess of Dalhousie? Why did she own this first American edition of Emma, rather than John Murray’s London edition? What did she think of Austen’s writings? How and why did this copy pass from her hands? These questions, which have long intrigued book historians and professional bibliographers, hold considerable importance, given the paucity of existing information about Austen’s early publication and readership in North America.

A first set of answers appears as penciled notes on the endpaper of the first volume, opposite the bookplate:

Countess of D. wife of the 9th Earl. (1770–1838). who was Governor of Canada, Nova Scotia, etc 1819–1828. This explains her owning this edition, which was unknown to G. Keynes when he compiled his Bibliography of Jane Austen, 1929.

Endpapers of 1816 Philadelphia Emma showing Countess of Dalhousie’s bookplate and penciled notes in Siegfried Sassoon’s handwriting. Courtesy Goucher College Special Collections & Archives.

The writer of these notes was the second documented owner of this copy, Siegfried Sassoon, the noted World War I poet. A letter from Sassoon accompanied these volumes as they passed, via purchase, to their next owners: the American bibliophile Frank J. Hogan, who added his lush bookplate below that of the countess; and the American Austen collector Alberta H. Burke, who placed her bookplate opposite. Mrs. Burke bequeathed the copy to Goucher in 1975.1

Like Sassoon before her, Mrs. Burke was very curious about the first owner of this rare copy. As she explained to the aspiring Austen bibliographer David Gilson, “I like to think, most romanticly, but with no evidence, that she [the countess] purchased it as a new novel when she was in Canada with her husband who was Governor-General there in 1819” (5 August 1967). Gilson uncovered a few more details about the Countess and her distinguished husband for inclusion in his A Bibliography of Jane Austen (1982): “This lady was Christian Broun (1786–1839), who married in 1805 George Ramsay, 9th Earl of Dalhousie (1770–1838), Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia from 1816 to 1819, and Governor in Chief of Canada, Nova Scotia, &c. from 1819 to 1828” (100). Regarding the countess’s ownership of Emma, however, Gilson ventured only that her copy “may therefore have been acquired in N. America shortly after publication” (101). How and when the copy left her possession Gilson also did not know; he described it as having been “in the present century found in Salisbury” by Sassoon (Gilson 101).

My endeavor to fill in these gaps in knowledge about Lady Dalhousie began with the published record. The few references to Lady Dalhousie in readily available print sources shed some light on her character and interests, but not on her reading in particular. She appears briefly, as a cheerful and beloved presence, in her husband’s diaries of his years of difficult leadership in British North America (published 1978–1982). She can be glimpsed, too, in René Villeneuve’s groundbreaking catalogue Lord Dalhousie: Patron and Collector (2008), which establishes the earl’s importance as the first patron of the arts in Canada. Villeneuve reproduces a delicate watercolor portrait of the countess created by William Douglas in 1816—the year of the Dalhousies’ departure for North America—that shows her with her youngest son, James. Douglas also depicted the earl in a separate, complementary work.

|

William Douglas, Christian Broun of Colstoun with Her 3rd Son, the Hon. James Ramsay (1816). |

William Douglas, George, 9th Earl of Dalhousie, with His Dogs Basto and Yarrow (c. 1816). |

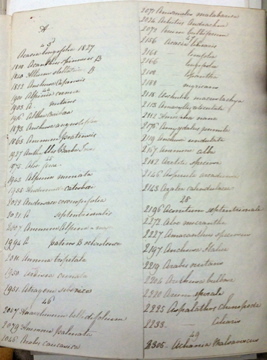

In his North American diaries, Lord Dalhousie mentions the countess’s interest in botanical collecting, the achievement for which she is best remembered today, and for which she was honored in her lifetime. An intact collection of Canadian plants formed by Lady Dalhousie, along with a catalogue list in her handwriting, is now in the holdings of the Royal Botanic Garden in Hamilton, Ontario.2 Also surviving is a portfolio of the countess’s lively watercolor depictions of Halifax social life, which was acquired by the Nova Scotia Museum in the 1980s as part of a larger group of Dalhousie documents (Elwood).

|

Preserved plant specimen of Campanula aparinoides, collected by Lady Dalhousie in Sorel, outside Quebec City, July 20, 1827. Courtesy R. B. G. Hamilton. |

Catalogue of North American plants formed by Lady Dalhousie. Courtesy R. B. G. Hamilton. |

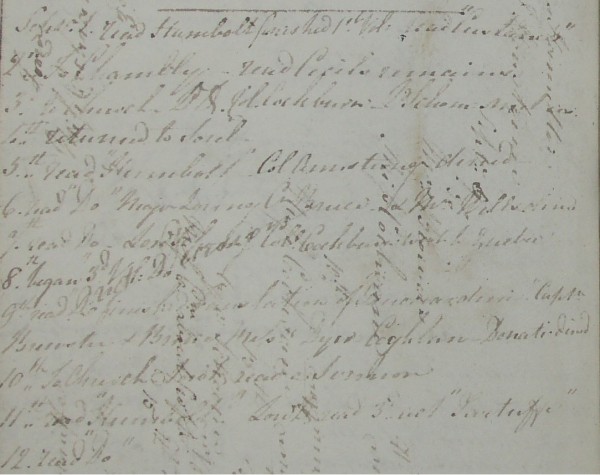

Fortunately for us, many more sources related to the countess have survived in private hands. Her personal papers, principally letters and diaries, constitute a treasure trove of information about her reading and book ownership. Preserved among her husband’s papers are account books and library catalogues that provide further valuable context for her ownership of the American Emma.

My chapter about Lady Dalhousie in Reading Austen in America presents an in-depth, chronological portrait of her as a reader, with the aid of a limited number of black-and-white illustrations. Here, I reverse the balance of words and pictures, conveying highlights of the countess’s life and reading via images of herself and of the places and people that mattered to her, as well as photographs of the key documents and artifacts that help answer our questions about her ownership of Emma.

Lady Dalhousie, née Christian Broun, was the daughter of a Scottish advocate (man of law) and grew up in comfort at Colstoun House, outside of Edinburgh. The need for funds to rebuild Colstoun after a 1907 fire likely caused the sale of valuable books from the countess’s collection, although it is not known how exactly Emma made its way to Salisbury.

Colstoun House as it appears today. Courtesy www.colstoun.co.uk.

Colstoun House as it appears today. Courtesy www.colstoun.co.uk.

Lady Dalhousie by Sir John Watson Gordon (1829). By permission of private owner.

Lining the entryway and public rooms of Colstoun are portraits of the countess, her husband, and her most distinguished son: James Ramsay, first Marquess of Dalhousie, who served as governor-general of British India from 1848–1856. (Also on display in the entryway are massive elephant feet and tusks that the marquess brought back from India.) The large-scale oil portrait of Lady Dalhousie is by the preeminent Scottish portraitist of the day, Sir John Watson Gordon. Gordon’s likeness of the countess’s face is severe, conveying none of the wit that is abundantly present in her writings. (A preparatory sketch from the same year offers a much livelier, more intimate view of the countess.3) Yet this very formal portrait offers important commemoration of Lady Dalhousie’s achievements, beyond the general learning signified by the book on her lap. The sheet of botanical illustrations to her left includes one of several plants that were named Dalhousiea in her honor, and the bird likewise represents a species named for her (Reid 118). We can only wish that Austen had been thought to merit a comparable portrait for posterity—and that any of her family could have afforded to commission one.

After a very conventional girlhood education, Christian married in May 1805, aged nineteen. Her husband was fifteen years her senior and had held his title and estate since the age of seventeen. (Notably, one of George Ramsay’s schoolmates at the Royal High School, Edinburgh, was Walter Scott.) The enormous financial demands imposed by Dalhousie Castle, the earl’s ancient, beloved family seat, were a lifelong burden to him. Indeed, the need to fund renovations to the castle furnished one of his main motives for taking up an administration post in British North America (Whitelaw 1: 15).

Dalhousie Castle as it appears today, by Rodney Yoder.

The Library Bar in Dalhousie Castle Hotel. Courtesy dalhousiecastle.co.uk/dining/.

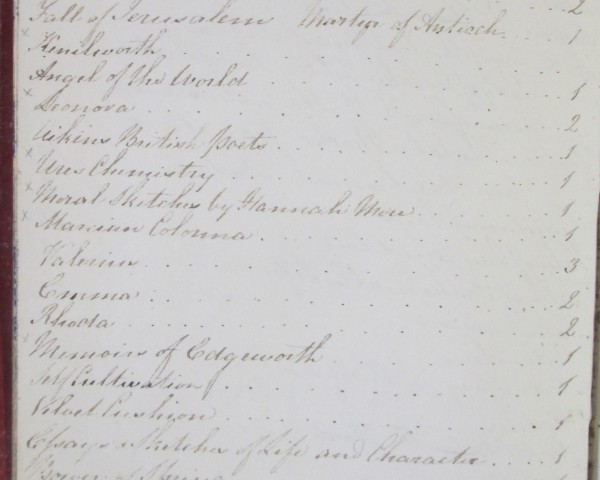

Dalhousie Castle operates today as a hotel, in which the historic Castle Library room serves as a bar. Still visible in that room are the bookcases that the earl commissioned as part of an 1830s renovation, using (it is said) imported Canadian hardwood. The design of the arched shelves matches the plans drawn on the endpapers of a catalogue of the library prepared at the same time. No works by Austen appear in this catalogue, although the earl did own quite a number of novels, including—not surprisingly—plenty of works by Scott. Evidently, as her bookplate and signature indicate, Emma was part of the countess’s personal collection.

Plans for Dalhousie Castle Library from early 1830s catalogue.

By permission of private owner.

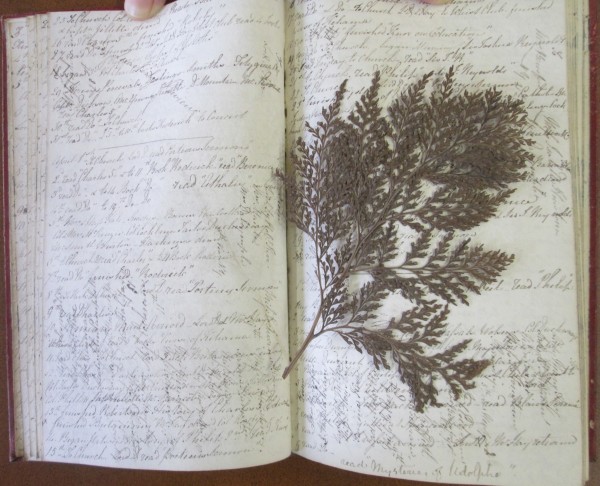

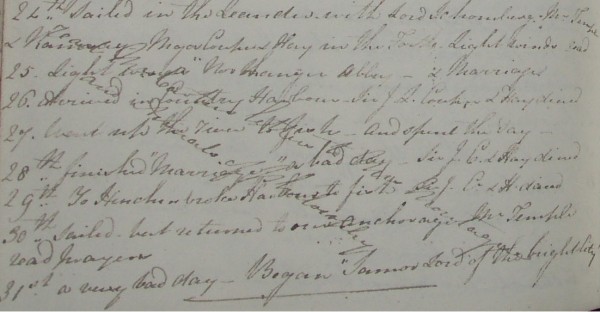

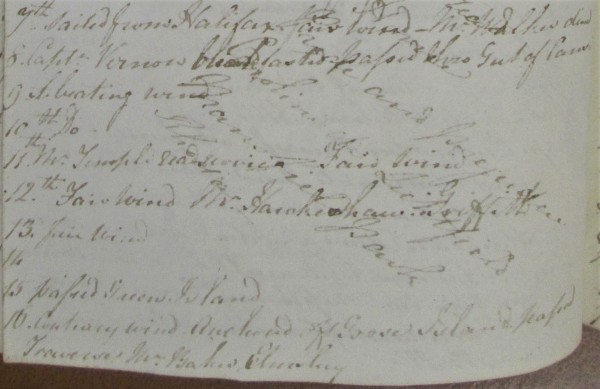

What Lady Dalhousie read and when is easy to track, in theory, thanks to her habit of listing her day’s reading in her diaries, along with plays attended, visitors hosted, and travel undertaken. While her handwriting is generally very legible, her North American diaries can nevertheless be quite challenging to decipher. Not only did she cross-hatch her pages to keep track of letters received and letters sent, but she sometimes listed titles read diagonally as well as horizontally. Furthermore, she maintained her lifelong habit of inserting plant specimens and other finds into her diaries, some of which have left significant “shadows” on facing pages. In some of her diaries, too, faded or degraded ink has made her entries very faint.

Pages from Lady Dalhousie’s 1819 diary, on which the title “Mysteries of Udolpho” is visible on the bottom right. By permission of private owner. NRAS 2383/3/60

(Click here to see a larger version.)

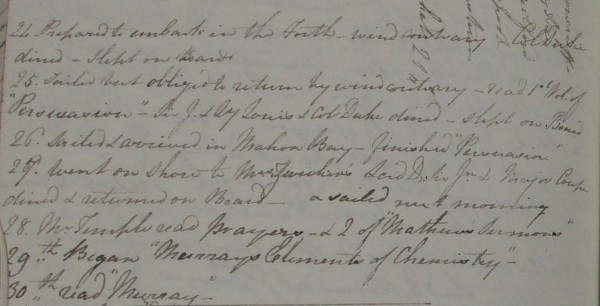

Given all these obstacles, it is remarkable that Lady Dalhousie’s reading of several Austen novels can be discerned. Her earliest record is for Persuasion, of which she read the first volume on June 25, 1818, and which she finished on June 26th. Her speedy reading was aided by her circumstances: she was on board a ship, the Forth, which was endeavoring to sail from Halifax to Mahone Bay (the countess spelled it “Mahon”). With the “wind contrary,” the passengers “slept on Board” until they could sail successfully on the 28th. The delightful coincidence of reading Persuasion while onboard a ship—even a stationary one—needs no explanation. Listed on the same diary page are other titles that accurately represent Lady Dalhousie’s range of reading, including “Mathews Sermons” and “Murrays Elements of Chemistry.”

Portion of page from Lady Dalhousie’s June 1818 diary, showing her reading of Persuasion. By permission of private owner. NRAS 2383/3/60.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Northanger Abbey was next, in September 1818. Once again, the countess was traveling, this time in the Leander, and once again she could devote herself, apparently, to very quick reading: she noted having read both Northanger Abbey and Marriage on September 25, finishing the latter on the 28th.

Portion of page from Lady Dalhousie’s September 1818 diary, showing her reading of Northanger Abbey. By permission of private owner. NRAS 2383/3/60.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

(Marriage was published anonymously in 1818 by Susan Ferrier [1782–1854], who is often called the “Scottish Jane Austen.”) After that, the countess took a break from Austen until June 1820, when she read Mansfield Park and Pride and Prejudice while en route from Halifax to Quebec, where the earl was to take up his new position of governor-in-chief of British North America.

Portion of page from Lady Dalhousie’s June 1820 diary, showing her reading of Pride and Prejudice and Mansfield Park. By permission of private owner.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

But what of Emma? My repeated scrutiny of Lady Dalhousie’s diary pages has yielded no definite entries. In a letter to a friend, she mentioned that she did a great deal of reading during the month of September 1820, while staying at the country retreat of Sorel, outside Quebec (to Mrs. Anderson, 26 September 1820). Her 1820 diary pages, however, are especially faint and hard to read; a short word like Emma could easily disappear. A particularly illegible diagonal entry opposite her entries for September 8 and 9 may possibly contain a note for Emma.

Portion of page from Lady Dalhousie’s September 1820 diary, with illegible entry that could possibly read “Emma.” By permission of private owner. NRAS 2383/3/61.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

The likelihood of the countess having read Emma in 1820 is substantiated by her inclusion of it on a 141-item list of books on the back pages of the diary volume she began on September 1, 1819. Apparently drawn up in preparation for the Dalhousies’ move to Quebec in June 1820, the list includes the number of volumes per title: “2” in the case of Emma. While the list begins in alphabetical order, the last third of the entries are not alphabetized, implying that the countess added those latter entries in the order in which she acquired the books. Several of the titles surrounding Emma can be cross-referenced with the countess’s diary entries from June 1820 to November 1821.

Portion of page from Lady Dalhousie’s book list in her 1819 diary volume, showing Emma.

By permission of private owner. NRAS 2383/3/61.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Mere lists of books read and owned, of course, do not tell us about the countess’s experience of or reactions to reading Austen’s novels.4 Lady Dalhousie’s letters to friends at home in Scotland frequently mention what she was reading (often the newest Scott novel) and what she thought of it. None of her known surviving letters, however, include discussions of Austen. Nevertheless, telling glimpses of Lady Dalhousie’s sensibility can be found in another medium: watercolor, in which she rendered lively, satiric images of Halifax society. Her colorful, wry depictions of well-dressed women and men in uniform reveal her sharp, unsparing eye and her considerable wit.

Watercolor of Nova Scotia society by Lady Dalhousie (c. 1818). Courtesy of Nova Scotia Museum.

Watercolor of Nova Scotia society by Lady Dalhousie (c. 1818). Courtesy of Nova Scotia Museum.

Further context for the physical condition of Lady Dalhousie’s copy of Emma can be found in the surviving remnants of her personal library, which includes both American and British imprints. Her use of a vertical signature on title pages to mark ownership appears in several other volumes, including copies of the 1823 New York edition of J. G. Lockhart’s Reginald Dalton and of the 1820 Edinburgh Ivanhoe.

|

Title page of Lady Dalhousie’s copy of Reginald Dalton. By permission of private owner. |

Title page of Lady Dalhousie’s copy of Ivanhoe. By permission of private owner. |

She signed her books in exactly the same way that she signed her letters. Evidently, the countess adopted the practice of the simple vertical signature in adulthood: a rare survivor from her childhood library bears the elaborately flourished designation “Cn Brown / Coalstoun.” (In Lady Dalhousie's lifetime, her family name was alternately spelled "Brown" and "Broun.") In rare instances, the countess added dates and places of purchase below her signature, as in a copy of an 1820 New York printing of Essays and Sketches of Life and Character (by “a gentleman who has left his lodgings”), which bears her annotation “York, U. C. [Upper Canada]― / 11th Feby / 1821―.”

Portion of letter from Lady Dalhousie to Mrs. Anderson, showing the countess’s signature. By permission of private owner. NRAS 2383/3/261.

Book showing Christian Broun’s signature.

By permission of private owner.

The unadorned bookplate that appears in the countess’s Emma, however, has no counterpart among the remnants of her collection. A few surviving volumes contain a small, square bookplate with a crown over the initials “C B D.” The design of this bookplate is very similar to that of the seal the countess used for her letters. By contrast, Lord Dalhousie’s much more elaborate bookplate incorporates the motto of the Order of the Bath (“tria juncta in uno”), into which he had been inducted following the Battle of Waterloo; the Dalhousie family motto (“ora et labora”); and heraldic elements.5

|

Bookplate bearing Lady Dalhousie’s initials. By permission of private owner. |

Lady Dalhousie’s seal. By permission of private owner. |

Lord Dalhousie’s bookplate. By permission of private owner. |

The binding of Lady Dalhousie’s Emma lacks a close counterpart among her other surviving books. Fully bound in leather, her Emma features a delicate border on the covers and a gilt-ornamented spine on which vignettes of plants and birds alternate with decorative horizontal elements, with a shield shape in the lower half of each spine containing the volume number. The title “EMMA” is stamped directly on the spine, rather than on a background of colorful leather. The lack of clarity in the stamping suggests a modest level of workmanship; further blurring has resulted from time and use. The differences in binding design between these two volumes and others owned by the countess are apparent; note the half binding (leather on spine and corners only) visible on the top and middle volumes of the stack and the red title labels on several.

|

Spines of Lady Dalhousie’s copy of Emma. Courtesy Goucher College Special Collections & Archives. |

|

Other surviving volumes owned by Lady Dalhousie. By permission of private owner. |

Since the binder of Lady Dalhousie’s copy of Emma left no interior label giving his name, his identity—like that of the bookseller from whom she bought the volumes—can only be guessed from entries in Lord Dalhousie’s cash and account books. An 1823 payment of £10, 19s. to “Carey Bookseller” was an order not from Mathew Carey in Philadelphia, alas, but instead from Thomas Cary of Quebec, where the Dalhousies were then living. (The keeper of Lord Dalhousie’s accounts elsewhere used the spelling “Cary.”) In Quebec, the Dalhousies also purchased books from “Neilson Book Seller,” and they frequently patronized “Lodge the bookbinder.”6 While living in Halifax, they regularly ordered books and maps from New York and Philadelphia, both cities in which Emma was for sale (Wells, “1816 Philadelphia Emma” 166). Payments for library subscriptions held by Lord and Lady Dalhousie respectively, as well as fines and “forfeits” incurred by each, appear in the cash and account books as well. Clearly, and not surprisingly, considerable investment was required to support the couple’s reading habits and book ownership.

Portion of page from Lord Dalhousie’s 1823 cash book, with entry “To Carey Bookseller” visible near bottom. By permission of private owner. NRAS 2383/3/102.

Lord Dalhousie’s cash and account books include no titles of books acquired, and only occasionally specify who made a particular purchase or commissioned a binding. Those rare references do confirm, however, that Lady Dalhousie was actively buying books and having them bound, in addition to receiving books sent from Scotland by friends, as often mentioned in her letters. “Books bought from N.Y. for Lady Dalhousie in 1817 £1.18.9” reads an entry in the February 1820 cash book. “To Lodge the Bookbinder a book for Ly D 3 | 6” (3s., 6d.) reads an entry from January 1821. Further research on early Canadian bindings, including comparisons with the work of known binders, may yield more definitive information. Certainly, Lady Dalhousie’s decision to have her copy of Emma fully rebound in leather has been crucial to the volumes’ preservation, given the cheap production values of Carey’s edition (Wells, “1816 Philadelphia Emma” 169). The decorations on the spine and covers of the countess’s copy suggest, too, that she cherished the book.

Portion of page from Lord Dalhousie’s 1821 cash book, with entry “To Lodge the Bookbinder” visible. NRAS 2383/3/102.

By permission of private owner.

In addition to her significance as an early North American reader and owner of Austen, Lady Dalhousie earned a place in Canadian literary history as the patron of the country’s first native-born novelist, Julia Catherine Beckwith Hart (1796–1867). Hart’s St. Ursula’s Convent, or the Nun of Canada (1824), published anonymously and by subscription, bore a heartfelt dedication to Lady Dalhousie. According to a contemporary review, the dedication appeared “by permission” (qtd. in Lochhead xxix); otherwise, nothing is known of the circumstances of Lady Dalhousie’s acquaintance with or encouragement of Hart. Today, copies of St. Ursula’s Convent are almost as rare as those of the 1816 Philadelphia Emma: according to the Canadian novel’s twentieth-century editor and champion, “[o]nly six, possibly seven, copies are known to have survived out of a press-run of probably about two hundred” (Lochhead xiii).

|

Title page of Julia Catherine Beckwith Hart’s St. Ursula’s Convent. www.openlibrary.org. |

Dedication page of Julia Catherine Beckwith Hart’s St. Ursula’s Convent. www.openlibrary.org. |

Both the phrasing and the format of Hart’s dedication are strongly reminiscent of Austen’s dedication of Emma to the Prince Regent, though of course Hart’s sincere tone could not be more different from the excessive humility in which Austen cloaked her disdain. Might Hart have seen Lady Dalhousie’s copy of Emma before composing her tribute? While far-fetched, the possibility is tantalizing, as a connection between one anonymous woman novelist and her forgotten edition, via a reader, to another.

Dedication page of Austen’s Emma (1816 Philadelphia edition). Courtesy Goucher College Special Collections & Archives.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to the generosity of donors, including many members of JASNA, the Goucher College Library has fully digitized its copy of the 1816 Philadelphia Emma. The open-access edition is available at www.emmainamerica.org.

My research on Lady Dalhousie was made possible by the Isabel Dalhousie Fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Study in the Humanities, University of Edinburgh. I am very grateful to Mr. Alexander McCall Smith for his support.

NOTES

1For a complete chronology of the Dalhousie copy’s owners, see Gilson 100–01.

2The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography identifies Lady Dalhousie as a "hostess and botanical collector" (Browne). On the extent and importance of Lady Dalhousie’s collection at the Royal Botanic Garden, see Pringle. A brief treatment of the countess as a botanist appears in Horwood. A recently created Wikipedia page has brought Lady Dalhousie to a wider audience.

3See Wells, Reading Austen in America, figure 3.1.

4In Reading Austen in America, I reconstruct Lady Dalhousie’s probable responses to Austen’s novels by drawing parallels between her experiences and those of Austen’s characters, especially in Persuasion and Emma; I also point out points of similarity and difference between Lady Dalhousie’s life and Austen’s own. I acknowledge too the remarkable coincidence between the countess’s reading of Austen in and near Halifax in 1818–1820 and the July 1815 reading of Mansfield Park by Lady Sherbrooke, Lady Dalhousie’s predecessor as wife of the lieutenant governor, and her friend Mary Woodhouse, which Emsley and Kindred have beautifully recounted.

5The motto “ora et labora” was adopted in 1870 by Dalhousie University, an institution founded in 1818 by Lord Dalhousie (Waite 98).

6I identify these booksellers and bookbinders in Reading Austen in America (133 n. 132).