|

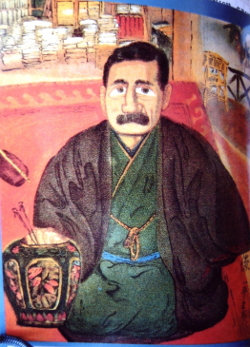

Natsume Sōseki went to London in 1900 to study English literature. There he read Jane Austen’s novels, and Austen remained a very important writer for him through his life. As is evident in his Theory of Literature (1907), he was impressed by her natural delineation of characters, and he highly valued her realism.1 Toward the end of his life, when he was writing his last and unfinished novel, Meian (Light and Darkness, 1916), he often talked about sokuten kyoshi, and mentioned Austen as an author who embodied this ideal. He produced a work very similar to, and at the same time very different from Pride and Prejudice, as critics have pointed out.2 Both Light and Darkness and Pride and Prejudice treat the themes of love and marriage, pride and prejudice, and class consciousness in settings of daily life, but the tone of each novel is very different. While Pride and Prejudice shows its two protagonists in the process of the overcoming of pride and prejudice, Light and Darkness explores in its leading couple the vicious circle of alienation pride and prejudice cause. Absorbing Austen’s techniques, the greatest modern Japanese novelist tried to explore the psychological depths of the relationship between a married couple more minutely. This section will focus on Sōseki’s idea of sokuten kyoshi and his narrative techniques, such as the elaborate use of dialogues and letters.

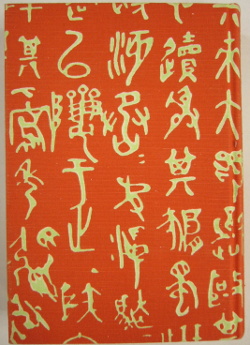

Let us begin by examining the idea of sokuten kyoshi. As Sōseki left no written explanation under his own name, we have to try and understand what he meant from some clues (Sasaki 216). Sokuten kyoshi is often translated as “follow Heaven, forsake the self,” the version given in our introductory essay, but the word has other connotations. The taishō rokunen bunshō-nikki (Writing Diary for 1917) includes a reproduction of Sōseki’s calligraphic writing of this phrase, adding that it is his motto, and explicating it as follows: “This phrase reads, ‘follow ten and leave self.’ Ten is nature. The expression sokuten kyoshi means that by following nature, we should abandon our little subjective self and artificial techniques, and that the writing should be natural and flowing.”3 Matsuoka Yuzuru, one of Sōseki’s disciples, writing in 1934, recalls Sōseki’s words: “Recently, I have attained a mental state, which I call sokuten kyoshi. . . . It means that I have abandoned my little self (ego) and have entrusted myself to the guidance of a larger universal self. . . . I am writing Light and Darkness with such an attitude” (214-15). Thus, Sōseki views sokuten kyoshi in terms of artistic technique and the author’s attitude, as Sasaki points out (221-22).

Sōseki regarded Austen as an artist who created “art without a self,” that is, a literary production in which she has erased herself.4 He regarded Pride and Prejudice as the embodiment of the ideal of sokuten kyoshi (Matsuoka Yuzuru 155), and he himself tried to achieve it in Light and Darkness.

While in Pride and Prejudice Darcy and Elizabeth deepen their mutual understanding by overcoming their pride and prejudice, in Soseki’s Light and Darkness pride overcomes and distorts the relationship of a married couple, particularly because, in some ways, they understand each other too well.

Light and Darkness is a story about Tsuda and his wife, O-Nobu, who have been married about six months, and those around them: their relatives, Tsuda’s boss Mr. Yoshikawa, and his wife, Tsuda’s friend Kobayashi, and his former love Kiyoko. Most of them belong to the middle class. Only Kobayashi, Tsuda’s friend, is a poor journalist and professes himself a socialist and an outsider to respectable society. He feels the class prejudice and disdain of Tsuda and O-Nobu toward him. Tsuda and O-Nobu married for love. Tsuda suffered from Kiyoko’s sudden rejection and married O-Nobu on the rebound, while O-Nobu married him because she believed that she had seen his true nature and that she would be happy with him. They are leading an extravagant life, depending on monthly financial support from Tsuda’s father. Tsuda, however, has not told O-Nobu that the arrangement was made on the condition that Tsuda pays back a part of the sum from his bonus. Tsuda breaks his promise and falls into financial difficulties as his father stops his support.

The story, in its unfinished state, covers only about a fourteen-day period. Tsuda is told by the doctor that for a complete cure, he should have an operation for his fistula. He stays at the clinic for about a week after the operation, and then goes to a hot spring to see Kiyoko under the guise of convalescence.

Sōseki introduces Tsuda and O-Nobu and develops their relationship through the skilful use of dialogues. In Theory of Literature, Sōseki admires the conversation between Mr. and Mrs. Bennet at the beginning of Pride and Prejudice. He highly values Austen’s technique, which makes the conversation not only “the distillation of an entire life,” but also the foreshadowing of “potential transformation” (111). The latter function is very important because he believes that the changes caused in the face of fate come out of the “normal state” (111). He successfully embodies this idea in a famous scene, their first conversation, from chapter three of Light and Darkness, by showing the couple’s domestic routine, their respective natures, and their relationship, with the added suggestion of problems being hidden beneath their politeness. Their conversation is a typical one which occurs, with variations, throughout the novel:

As he turned the corner and entered the narrow lane, Tsuda recognized his wife O-Nobu standing in front of their gate. She was looking his way, but as soon as his shadow emerged from the corner she turned to face straight ahead. She then placed her delicate white hands on her forehead as if shading her eyes, and appeared to be looking up at something. She did not change her position until Tsuda had come very close to her.

“Well, what are you looking at?” As soon as O-Nobu heard his voice, she turned to him in great surprise. “Oh, you startled me!―But I’m glad you’re back.” As she spoke, she brought together all the brilliance her eyes possessed and cast the full force of it on him. Then she leaned forward somewhat and bowed slightly. Tsuda half attempted to respond to his wife’s coquetry and half held back hesitatingly. “What on earth were you doing standing there?” “I was waiting for you.” “But weren’t you looking at something very intently?” “Yes―those sparrows. They’re building a nest in the eaves of the second storey of the house across from us.” He glanced up briefly at the roof of the house across from them, but he could not see a trace of anything resembling a sparrow. O-Nobu immediately put out her hand in front of him. “What’s that?” “A cane.” As if he had noticed it for the first time, Tsuda handed her the cane he was carrying. After taking it, she opened the lattice door of the entrance by herself and let him go in first. Then she followed him into the house. (4)

This is a common scene where the wife welcomes her husband in a polite but somewhat coquettish way. O-Nobu is polite and quick, and fulfils her role as wife very well. Nevertheless, there is a lack of naturalness and openness in the attitudes and conversation of the couple. O-Nobu’s artifice is clear in her pretence of not seeing him, and this artifice reveals itself in the conversation that follows, while Tsuda hesitates to show his natural response to O-Nobu. His feeling of “the full force” of her brilliant eyes suggests the power struggle lying beneath an apparently calm life.

Both Tsuda’s reserve and O-Nobu’s artifice originate from their pride. It is not too much to say that Tsuda’s pride rules everything for him and leads to his self-deception. Out of pride, he makes every effort to conceal from O-Nobu his financial difficulties and the existence of Kiyoko. Then his efforts force him to create other secrets and to tell lies. For O-Nobu too, it is most important to keep her pride intact. She had prided herself on her discernment, as did Elizabeth Bennet, and married Tsuda, but her confidence is weakening. Therefore, she has to show herself to others as a happily married woman by hiding her real feelings and thoughts, even to her uncle, who is nearest to her in sympathy.

Like Austen, Sōseki uses letters effectively to reveal the characters’ pride, artifice and struggle. O-Nobu decides to make Tsuda love her, and expresses this in her letter to her parents. She writes about her happy married life in detail so as to please her parents, and then makes the following declaration to them in her heart: “What I’ve written here is the true state of things. . . . Maybe I’m the only one who knows this truth now, but in the future everyone will” (141). Thus, by creating her ideal self, she shuts her eyes to reality and, like Tsuda, deceives herself. This letter also symbolically shows the similarity and difference between O-Nobu and Tsuda. In Tsuda’s letter to his father asking for money, he superficially accommodates himself to his father’s traditional fastidiousness by writing in a formal epistolary style on rolled stationery, though he despises his father’s stingy ways. Tsuda’s letter shows the same artifice but not such a strong will as O-Nobu’s. It is worth noting the difference in the use of letters in Light and Darkness and Pride and Prejudice. The letters used in Pride and Prejudice reveal much of both the writer and the receiver, and often their significance is to reveal the thinking process of the latter, as, for example, in Mr. Collins’s letter to Mr. Bennet and in Darcy’s letter to Elizabeth. The letters in Light and Darkness, however, are one-way communications with no response given, a tactic that heightens the sense of dramatic irony and emphasizes the writers’ artifice based on their pride and prejudice.

Sōseki develops the Austenian themes of pride and prejudice by exploring the complicated and ironic way these qualities influence the characters’ relationships. Tsuda’s and O-Nobu’s pride sometimes ironically serves as an opportunity to realize a better, more open relationship. When Tsuda’s sister O-Hide visits him at the clinic to offer money of her own to help him, he is so proud as to respond with sarcastic words to her offer, and she criticizes him for his selfishness. They continue to argue until O-Nobu, who has been eavesdropping on their conversation, enters the room and produces the check she has received from her uncle. This incident not only becomes an opportunity for O-Nobu to learn his real financial situation but also unexpectedly serves to create some openness between Tsuda and O-Nobu. Tsuda’s heart, which has been guarded to preserve his dignity, softens involuntarily, and O-Nobu opens herself up to him naturally without noticing it. It is ironic that their openness and sense of solidarity come from their pride and egotism, offering a chance for their change.

But at other times pride and prejudice combined with class-consciousness make it inevitable that O-Nobu use more artifice, gradually driving O-Nobu, a young woman of spirit and independence, into a further vicious circle of alienation in spite of her desire for love. O-Nobu has to fight a hard battle when Kobayashi suggests the existence of Kiyoko to her. As both Tsuda and O-Nobu despise Kobayashi because of their class-consciousness and prejudice, Kobayashi retaliates for their affronts by intentionally making them more anxious. O-Nobu directs her efforts to extracting Tsuda’s secret from O-Hide and Tsuda himself by manipulating conversations with them and using trick questions, but in vain. She is convinced that she can love Tsuda, and eagerly wishes to “be loved absolutely” (246) by him. Like Elizabeth Bennet, in emphasizing love rather than the traditional view of marriage, she is a new type of woman. She, however, does not think about how she should love him. She neither thinks of changing herself nor is aware that she further alienates Tsuda by trying to find out his secret. Therefore, her struggle is pathetic and sometimes even comical because of her paradoxical cleverness and blindness.

As for Tsuda, his calculating pride makes him incapable of responding naturally to his wife when she confronts him with an honest and desperate appeal for confidence. While worrying that O-Nobu may ferret out his secret, Tsuda decides to go to see Kiyoko under the pretext of convalescing in a hot spring where she is staying alone. Tsuda acts on the advice of the Lady Catherine-like Mrs. Yoshikawa, who has a prejudice against O-Nobu and interferes with Tsuda’s private matters. On the other hand, O-Nobu can no longer contain her suspicion and anxiety, finally evinces them, and entreats Tsuda to tell her everything. He answers:

“Everything’s all right. Don’t worry, I tell you.” “Do you really mean that?” “Yes, I do. Please stop worrying.” She immediately pounced upon these words with startling force. “All right then, tell me. Please tell me. Tell me everything right here and now without holding anything back. And really put my mind at ease once and for all.” Tsuda was taken aback. His mind began to waver in uncertainty as he wondered whether he dared reveal to her everything about Kiyoko. But he quickly concluded that he was then only suspected and that it was not that O-Nobu held any actual evidence against him. He also decided that if she really knew the facts of the case she would hardly have pushed him that far without thrusting them at him. (287)

From a detached point of view, the narrator reveals the power struggle between the couple, which lurks in their genuine love and distorts it:

Even though he viewed his married life with O-Nobu as a battle over love and even though he had always been the loser, he also had considerable pride. And since he had been subjugated by O-Nobu against his will, he had obviously not given himself up to her from the heart. It was not that he splendidly became a prisoner of love but rather that he was always being duped by her. Just as O-Nobu, without realizing that she was undermining his pride, felt the satisfaction of love only in vanquishing him, so too did Tsuda, who disliked losing, surrender each time that his strength was not equal to hers and he was pinned down, although he still regretted so doing. . . . While still retaining his vulnerable point and trying to dodge her thrusts, he had for the first time been able to beat her. The result was clear: he could finally despise her. But at the same time he could sympathize with her more than before. (289)

Sōseki thus develops the themes of pride and prejudice in a very different direction from Austen, but still in a style reminiscent of Austen’s irony and comedy.

A good example of this irony is found in the conversation between Tsuda and Kiyoko. The meeting of Tsuda and Kiyoko eventually occurs at an unexpected moment at the spring, surprising both of them very much. Later, when Kiyoko says that she thought he had been lying in wait, he presses her for an answer as to why she thought so. Their conversation is an exchange of words which satisfies neither of them, and Kiyoko finally answers:

“The reason’s very simple. It’s just that you’re the kind of person who’d do that sort of thing.” “You mean lie in wait for you?” “Yes.” “Don’t be ridiculous.” “But as I see you, that’s the sort of person you are, so I can’t help it. I’m not lying or saying anything untrue.” “I see.” He folded his arms and looked down. (370-71)

Tsuda is helpless in the face of Kiyoko’s simple words. This conversation not only makes a strong contrast with those he has with O-Nobu, but it also suggests an unbridgeable gap between Kiyoko and him. However, very ironically, Kiyoko’s words, “you’re the kind of person who’d do that sort of thing” indicate the answer which Tsuda craves. Kiyoko must have realized his artifice, abhorred it, and left him.

As we have seen, Sōseki explores how pride overcomes and distorts the relationship of a married couple with the masterly use of dialogue and letters. The effectiveness of the dialogues is more prominent in their combination of the third-person narrative, which not only heightens the sense of dramatic irony but also conveys the possibility of psychological changes in characters. Above all, it is remarkable that Sōseki is successful in not imposing himself to a great extent.

This self-effacement is evidence of the evolution of this great writer, whose previous novels had often displayed autobiographical aspects which constituted his intrusion into the story. The atmosphere of Light and Darkness is so gloomy and oppressive as to make the reader sometimes find it stifling, but we can see from a different detached point of view, the comicality that arises from men’s and women’s pride and prejudice. Sōseki presents the severe collision between two egos with the artistic techniques and attitude that he absorbed from Austen, and in this unfinished novel he approaches his ideal, sokuten kyoshi. We can say that he transformed the Austenian novel of manners into the more modern psychological novel. Notes 1. For his early response to Austen, see Sōseki, Zenshū 27: 30-33. Hogan and Brodey discuss his responses, but do not touch on the idea of sokuten kyoshi.

2. For example, Sasaki and Matsuoka Yōko.

3. Sōseki, Zenshū 26: 292; Ōno Jun’ichi, note, Sōseki Zenshū, 26: 548; Sasaki 216. The explanation as well as the picture of Sōseki’s calligraphy is printed in the note. It is difficult to decide if it was written by Sōseki himself. However, because the Writing Diary was published twenty days before Sōseki’s death, as Ōno and Sasaki argue, it might at least have been approved by Sōseki. We can also as Matsuoka Yōko points out, see the similarity between sokuten kyoshi and John Keats’s “negative capability” (150-51).

4. Oka Eiichirō, “Natsume sensei no omoide” (Reminiscences of Teacher Natsume), Osaka Asahi 26 December 1916, qtd. in Sasaki 217. Works Cited Hogan, Eleanor J., and Inger Sigrun Brodey. “Jane Austen in Japan: ‘Good Mother’ or ‘New Woman.’” Persuasions On-Line 28.2 (2008). Matsuoka, Yōko McClain. Magomusume kara mita Sōseki [Sōseki as Viewed by His Granddaughter]. Tokyo: Shinchōsha, 1995. Matsuoka, Yuzuru. Sōseki sensei [Teacher Sōseki]. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1934. Natsume, Sōseki. Theory of Literature and Other Critical Writings. Ed. Michael K. Bourdaghs and Atsuko Ueda, Joseph A. Murphy. New York: Columbia UP, 2009. _____. Light and Darkness. Trans. V. H. Viglielmo. Tokyo: Tuttle, 1972. _____. Sōseki Zenshū [The Complete Works of Sōseki]. 28 vols. and supp. Tokyo: Iwanami, 1993-97. Sasaki, Mitsuru. Sōseki suikō [A Study of Sōseki]. Tokyo: Ōfūsha, 1992.

|