|

Two years after her inaugural dust up with pirates (Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl), Keira Knightley starred as Elizabeth Bennet in Joe Wright’s adaptation of Pride & Prejudice (2005). At first glance, the staid costume drama would seem to be worlds apart from the rollicking adventure flick in which Knightley’s capture by pirates actually liberates her from an arranged marriage and conventional life ashore. Yet Jane Austen’s most popular novel arguably explores a similar theme: the tension between women held captive by Regency social strictures, especially around marriage, and their ability to cut loose—or, at least, to exert a modicum of free will. My project here is to consider the most recent cinematic Pride & Prejudice (with reference to the 1940 film as well as to Austen’s novel) in order to gauge its depiction of female agency within a limiting social context.1 As we will see, the 2005 film features an Elizabeth Bennet with significant freedom to indulge her piratical tendencies—a characterization at odds with Austen’s darker view of female development as, in large part, the forcible curbing of these. Beginning with a close analysis of the first five minutes of Wright’s adaptation, I want to suggest that his Elizabeth is framed from start to finish as a kind of rogue figure: mobile, natural, freely idiosyncratic, and largely outside the social matrix. Ironically, this “updating” of Elizabeth—perhaps with younger, post-feminist viewers in mind—comes at the expense of Austen’s own proto-feminism, which would call our attention to women’s lack of freedom in the Regency period.

Wright’s movie begins with the sound of early morning birds and a long shot of the English countryside at dawn. The effect is of a gentled wilderness—neither farmland disciplined by hedgerows nor the harsh gloom of Brontë country. As the sun rises, we hear the rolling notes of a simple, classical-sounding piano melody. The twenty-first-century score is by Dario Marianelli, but it channels early Beethoven to locate us in a semblance of Austen’s England, a place of genteel country houses and politely passionate courtship rituals. Cut to a medium shot of Knightley already in motion, walking directly into the camera. She is wearing a homespun dress, looking gorgeous as usual, and reading a book that apparently amuses her. The subsequent shot has us looking over her shoulder at the book in question, which she then closes and caresses fondly. The gesture invokes our own, presumed affection for reading as well as screening the works of Jane Austen. It further characterizes Lizzy as not only a walking but also a reading kind of girl, and it establishes her point of view as the predominant one.2 For the duration of the film, as in Austen’s novel, we will go where Elizabeth takes us, and see things more or less as she does.

Cut next to a long shot of the humble Bennet property, which Elizabeth approaches from the back by crossing over a kind of poor man’s moat, ducks flocking in the muddy water. The key signifiers here are livestock and laundry—lots of laundry blowing poetically and occasionally blocking our view of Elizabeth as the camera tracks her progress through the Bennet yard.3 Soon we come to an open doorway, and here our paths suddenly diverge, for Lizzy continues in the bright out-of-doors while we follow the camera forward into the dark interior. Bringing us more fully into the world of the film, the music we hear is now redefined as diegetic (within the world of the characters)—the plain, geeky sister, Mary can be seen from the back, playing it on the family piano. Two more Bennet girls hurtle by in a fit of giggles; we know one of them is Lydia, because a fifth, statuesque sister calls out her name. As a rangy dog wanders through, the camera turns to pan slowly over a dining table strewn with dishes, a beribboned hat, and some messily heaped fabrics; later, continuing the textile motif, we will see a garland of newly-dyed ribbons hung up to dry. Overall, the impression of this domestic space is cozy and pleasantly chaotic. And if the washed linens, piled muslins, and colored ribbons define this as very much a feminine sphere, they also suggest that, for these girls, the trappings of gender are apt to waft prettily, rather than to bind.

Having introduced the Bennet daughters, the camera takes us out another door, reuniting us with Lizzy mid-stride, still crossing the yard, still clutching her book. Now pause with our heroine before a window and see, looking over her shoulder and through the leaded panes, Mr. and Mrs. Bennet conversing within. In keeping with the novel, it is Mrs. Bennet who speaks the first words of dialogue, “My dear Mr. Bennet, have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?”

© 2005 Focus Films

The family discussion about visiting Mr. Bingley follows soon after, and here I would note that Elizabeth is clearly aligned throughout not with her mother and sisters but rather with her father. Like him, she appears to regard the marital hopes and anxieties of the other female Bennets with amused detachment, as if they had little to do with her. The last shot of this scene explicitly pairs father and favorite daughter. While the others romp and chatter excitedly about the upcoming ball, Elizabeth and her father remain seated and unspeaking; facing the same way, they are positioned alike as observers of the action. Lizzy is smiling, and she seems to share her father’s ironic view of these feminine raptures.

Needless to say, successful adaptations from page to screen are never exact transcriptions but are, instead, creative translations that play to the strengths of a medium specializing in images over words. My point, then, is not to evaluate this film’s fidelity to Austen’s original, much less to find fault with some inaccuracy of period detail. I would ask, rather, whether Joe’s version of Jane succeeds in getting at the gist of her heroine’s dilemma, whether it grasps the novel’s fundamental issues and explores them thoughtfully using the distinctive idiom of cinema.4 In these terms, as I say, my problem with Wright’s Elizabeth is how casually he releases her from the intricate social concerns—and more bludgeoning economic ones—that so thoroughly delimit the world and shape the destinies of Austen’s female characters. In Wright’s Pride & Prejudice, the tension Austen sets up between Elizabeth’s specialness and the norms of Regency femininity all but collapses. Instead of a superior girl painfully brought down a notch, Wright’s heroine is not only distinguished from the start but also enabled throughout to observe the world from well above the fray. Her elevated, securely privileged position in Wright’s film is most strikingly represented by a long shot of Knightley high atop a hill in Derbyshire. A lone figure, silhouetted against earth and sky, she looks out commandingly over the landscape, skirts billowing in the wind. Although this memorable shot comes in the movie’s latter half, not long after Elizabeth’s mortifying discovery of error regarding Mr. Darcy, it is not the image of a woman whose wings have been clipped or sails trimmed—quite the contrary.5

As we have seen, the film wastes no time in establishing Knightley’s character as both primary and exceptional. She is the first character we meet, almost the first thing we see; along with the chirping birds, she appears to be the only creature stirring at this very early hour. The countryside depicted is pleasant but bland; as a backdrop, it functions effectively as a blank canvas, enabling our heroine to stand out in sharp relief. It is she who proceeds to lead us home, who acts as our guide, showing us where we need to be. She does leave us briefly, however, and the camera’s momentary detour is key to my reading of Wright’s introduction. Recall that upon reaching the Bennet home, Elizabeth veers off from the entrance. By pointedly not entering, she separates herself from the other six Bennets, all of whom are to be found within. As I have mentioned, we first see Mr. and Mrs. Bennet pinned behind panes of leaded glass, and we do so from Lizzy’s vantage point, standing in the open air. Distinguishing her thus from the family inside, the film chooses from the first to locate Elizabeth out-of-doors and to mark her, over against social and familial norms, as a kind of outsider.6

Compare this placement of Elizabeth to that suggested by the 1940 movie. This first Hollywood adaptation opens with a shot of the town of Meryton. The camera pauses over the public space of the street, the mild bustle of people running errands, before moving inside a shop where Mrs. Bennet, Jane, and Elizabeth are conferring with a shopkeeper about muslins. The appearance of Mr. Bingley and Mr. Darcy in a carriage outside quickly generates a flurry of speculation about the two men’s marital status and income. Instead of remaining, like Keira Knightley, slightly apart from the gendered world of shopping, husband-hunting, and female rivalry, Greer Garson’s Elizabeth is located in the very thick of these. Instead of peering in from outside, this Elizabeth is always already inside. From here she joins the other women peering out, hoping to get a better look at the new men in town. The scene ends with Mrs. Bennet gathering up her other three daughters and hastening home so that Mr. Bennet can be the first to call on Bingley. Moving in unison down the street, their mother in the lead, all of them garbed in similar dresses and stiff bonnets, the sisters look like nothing so much as baby ducks, Elizabeth indistinguishable from the rest.

How does Austen’s novel introduce its heroine? Unlike either film, Elizabeth doesn’t actually appear at all in Austen’s first chapter, which is largely devoted to the humorously asymmetrical conversation between Mr. and Mrs. Bennet. There is yet no specific reference to the entail, but the perilous economic context is suggested by the book’s famous first sentence, invoking not only “a single man in possession of a good fortune” (3) but also, between the lines, a family of daughters possessing not much more than their own sexual capital. Beginning thus, the novel makes a point of framing Elizabeth not as sui generis or as some kind of child of nature but rather as the product of particular parents at a certain historical juncture. Unlike the recent movie, Austen’s Elizabeth doesn’t come strolling in from the wild but emerges very specifically from the bosom of a bad marriage. Indeed, the novel’s heroine does not even emerge as a compelling, individuated subject until several paragraphs into chapter three. As Alex Woloch explains in his study of characterization, Elizabeth’s status as a major character is not given from the outset but must be gradually established relative to the minor-ness of others (43-68). Consequently, by the time she is singled out as protagonist, she has also been embedded within a common framework, carefully situated in relation to a marital precedent and gendered economic logic, not to mention a scrutinizing male gaze.7

For Austen, then, despite her singular qualities and degree of self-determination, poor Lizzy must operate within the same parameters—social, economic, intellectual, and sexual—as other Regency-era females (a fact the 1940 film appears to appreciate). As his first few shots alert us, Wright will finesse these parameters by taking every opportunity to place Elizabeth against the backdrop of nature rather than society. We see her more than once seated at the foot of tree.

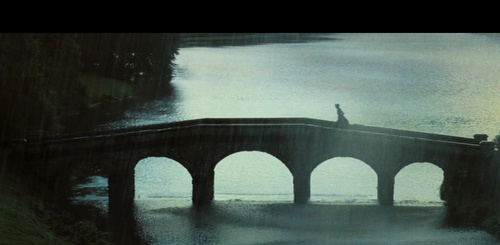

Not only the opening images and Derbyshire footage but also the first proposal and final reunion with Darcy all take place out of doors. In the novel, Darcy’s first proposal occurs in the Collinses’ house. The recent movie opts to defer and relocate the proposal to a picturesque ruin out in the wilderness.8 It is pouring rain, and both our romantic leads are looking half-drowned. The wet clothes, smudged mascara, bedraggled hair, and raw emotion seem to signify the triumph of nature and unfettered passion over the niceties of civilization. The scene has its counterpart in the second, successful proposal, which further echoes the film’s opening sequence described above. In all three scenes, Elizabeth crosses a bridge that might be said to figure the passage between nature and culture.

The last of these features a sleepless Elizabeth wandering outside at dawn, crossing the aforesaid bridge, and then suddenly glimpsing Darcy approaching through the mist. Whereas Austen’s couple confess their love enroute to the Lucases, scarcely out of sight of the others, Wright’s Elizabeth meets her Mr. Darcy, both of them still extremely disheveled, in a dream-like space beyond the borders of everyday consciousness and culture.

If all of this seems like something of a romantic cliché, it is one descended more from the Brontes than from Austen. Austen is, if anything, apt to mock those enraptured by picturesque notions of landscape, and she gives us multiple female characters censured for venturing out alone—Elizabeth foremost among them.9 I would note, in addition, that our heroine muddies her stockings by “crossing field after field” (32)—traipsing, that is, across neatly enclosed acres of farmland, not undomesticated countryside. Indeed, if Austen’s nature is well-known for being fenced and cultivated, she is even more a novelist of country towns and domestic interiors—of carriages, shops, and the Pump Room at Bath, of libraries, drawing rooms, ball rooms, and the small, tidy dwellings of Persuasion’s naval officers. As numerous critics have asserted, Austen is less about walking out past the strictures of society than regarding them satirically while endeavoring to navigate within their confines.10 Joe Wright’s adaptation seems thus deliberately to overlook a defining feature of the original: as her heroines would surely agree, in Austen country, there is no bridge away from culture and society.

Austen’s Pride and Prejudice is a satisfying romance, which nevertheless (like her corpus overall) includes an incisive critique of social institutions—courtship and marriage in particular—as seen from a female perspective. Joe Wright’s film gives us the satisfaction, while all but suppressing the critique. Its coda, especially, is so extravagantly romantic that it was cut from the British version. In this final sequence, our lovers sit in the dark on a kind of plinth, a reflecting pool and Pemberley’s spectacular façade visible in the background. Murmuring endearments, and carefully distinguishing themselves from Mr. and Mrs. Bennet, they embrace. I am not one of those purists who objects to Hollywood kisses. What I do mind, however, is the extra-social love bubble in which this kiss occurs. Wright’s closing shots isolate our lovers in the dark; they look dressed for bed, and the scene could almost have been set in the privacy of their bedroom. Not so in the 1940 film, which cuts away from Elizabeth and Darcy’s kiss to Mrs. Bennet, spying on the couple from a window. Comparing Lizzy’s fortune to Jane’s, urging Mr. Bennet to pursue a prospect for Mary, here Mrs. Bennet gets the last word—one that neatly folds the heroine back into a family of five daughters for whom marriage is an economic necessity. Of course Austen’s camera eye pulls back further still, requiring us to keep in mind the larger social as well as familial context. In sharp contrast to Wright, Austen leaves us contemplating Lydia’s loveless marriage and ongoing money problems, Georgiana’s lessons in more assertive womanhood, and Lady Catherine’s indignation at the “pollution” of Pemberley by Elizabeth and her lowly relatives.

By way of my own ending, I would call our attention to a brief, curious moment in Wright’s film, which seems fleetingly to suggest a less harlequinized, more ambiguous view of Elizabeth’s fate—one arguably closer to Austen’s feminist realism.11 The scene I have in mind occurs when Elizabeth and the Gardiners wander through the magnificent, art-filled public rooms of Pemberley.12 As Knightley studies a ceiling painted with cavorting nudes and admires the curves of some extremely buff statuary, the Darcy home is increasingly eroticized. Her expression is one of awe tinged with wistfulness and, increasingly, desire; by the time she recognizes a handsome bust of Mr. Darcy, it is clear her feelings toward the man have begun to soften. The moment that interests me, however, comes shortly before this, when Elizabeth has just entered the gallery. For the figure that first seizes and holds her attention is not the lounging youth wearing only a helmet but a standing woman, fully clothed and, what is more, completely veiled. Her face is, indeed, quite closely and confiningly swathed—I am tempted to say, suffocatingly so. Unlike the floating textiles seen earlier, her garments are made of stone, and the overall impression of this bride-like figure is rather grim.

Linda Troost identifies the statue as a “Vestal Virgin” by Raffaele Monti; according to Troost, the veil references Elizabeth’s own virginity, “slipping from her as she contemplates the naked figures” (494). I would like, instead, to stress the veil’s bridal connotations and cautionary implications (in keeping, here, with Austen’s novels). For as Lydia’s story suggests, female desire may not liberate but simply activate the mechanisms of compulsory heterosexuality. The veil of proper femininity may not slip away but only, upon marriage, bind more tightly. Knightley’s Elizabeth looks long and thoughtfully at this monitory figure and, as she walks away, compresses her lips just slightly. I suggest, in conclusion, that we keep this image of a muted and frozen maid somewhere in the back of our minds, even while appreciating Wright’s final shot of the incandescent “Mr. and Mrs. Darcy.” The reward for doing so will be a doubled picture that corresponds quite well with Jane Austen’s complexly rendered marriage plot. Notes All clips and images used in this essay satisfy the criteria for fair use established in Section 107 of the Copyright Law of the United States of America and Related Laws Contained in Title 17 of the United States Code.

1. The familiar film history of this novel begins in 1940 with MGM’s celebrated adaptation starring Lawrence Olivier and Greer Garson. Between 1952 and 1995, BBC alone produced five television miniseries based on Pride and Prejudice. Starring as Darcy in its 1995 version, Colin Firth made Austen-movie history—or at least his chest did, in the soft-core shot of him soaking wet after an impulsive swim. Bollywood added its own spin in 2004 with Gurinder Chadha’s Bride and Prejudice.

2. David Roche (with the help of digital enhancement) identifies Knightley’s book as none other than Pride and Prejudice. As Roche explains, if reading helps to characterize the heroine, closing the book comments on Wright’s own act of adaptation, suggesting that “the film will leave the novel aside in order to create something different.” According to Juliette Wells, the screenplay (by Deborah Moggach) specifically identified Elizabeth’s book as “First Impressions.” While the film never shows us a title, this detail would support Roche’s notion that Wright means to construe Austen’s text as a labile, preliminary version—the better to license his own revision.

3. Many critics have noted Wright’s “social realist” attention to Longbourn’s mud, pigs, and chickens. See especially Carol M. Dole’s fine essay on the tension between this idiom and, residually, that of the heritage film. Kathleen Anderson cites the pig as emblem of the film’s “Darwinian” vision, linking social and biological “fitness”; my reading accords with her view of Wright’s Elizabeth as a “literate but natural creature,” tied to the elements, superior to other women, striding into the film with energy and self-confidence.

4. For essays assessing the success and significance of Austen film and television adaptations over the years (with an emphasis on the late 1990s), two collections are of special interest: Troost and Greenfield’s Jane Austen in Hollywood (1998) and Macdonald and Macdonald’s Jane Austen on Screen (2003). Discussions in these volumes focusing on Pride and Prejudice include those by Cheryl L. Nixon, H. Elisabeth Ellington, Lisa Hopkins, and Ellen Belton. For a wealth of essays devoted specifically to Joe Wright’s adaptation, see the special issue of Persuasions On-Line (2007). See also Linda V. Troost’s “Filming Tourism, Portraying Pemberley” (2006), which contrasts the 1979, 1995, and 2005 depictions of Darcy’s estate.

5. Publicity materials for the movie and front material for the DVD version took this image as iconic. Austen, by contrast, portrays Elizabeth’s discovery of error as a profound “humiliation” (208). Upon receiving Mr. Darcy’s chastening letter, her Elizabeth comes to feel “absolutely ashamed” at having misjudged him. For more on my view of this moment as a crucial turning point, discrediting Elizabeth’s judgment altogether, see “The Humiliation of Elizabeth Bennet.” At the same juncture, Keira Knightley’s character simply becomes moody and introspective; none of Austen’s self-accusatory language is reproduced, and Knightley’s Elizabeth, staring into a mirror or lying awake in bed, looks to be more lovesick than self-hating.

6. See Mary M. Chan’s reading of space in Wright’s film, which shares my sense that Lizzy is located primarily in a romanticized, natural landscape, suggesting freedom from social restrictions.

7. See Barbara K. Seeber’s complaint, resonating with my own, that Wright softens Austen’s critique of the patriarchal family: like the 1940 film as well as Bride and Prejudice, he improves Mr. Bennet, simplifies the entail, and downplays marital strife.

8. Cf. Laurie Kaplan, who accuses Wright of “haphazardly” relocating numerous scenes, scrambling Austen’s metaphoric use of inside/outside to the point of “incoherence.” My own argument, by contrast, is that Wright’s relocation of Elizabeth outside is not haphazard but highly systematic—serving his portrayal of her as a girl more beholden to “nature” than “society.”

9. For more on Austen’s views of the picturesque—alongside the treatment of landscape in the 1995 Pride and Prejudice—see “‘A Correct Taste in Landscape’: Pemberley as Fetish and Commodity” by H. Elisabeth Ellington (95-97).

10. For a notable example of a feminist reading along these lines, see Gilbert and Gubar’s The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination (1979).

11. On the “harlequinization” of Austen’s novels, see Deborah Kaplan’s “Mass Marketing Jane Austen: Men, Women, and Courtship in Two Film Adaptations.”

12. For a fascinating reading of the gallery scene and its use of camera techniques borrowed from interactive media, see Joyce Goggin’s “Pride and Prejudice Reloaded: Navigating the Space of Pemberley”(2007). Works Cited Anderson, Kathleen. “The Offending Pig: Determinism in the Focus Features Pride & Prejudice. Persuasions On-Line 27.2 (Sum. 2007). Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. Ed. R. W. Chapman. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1965. Chan, Mary M. “Location, Location, Location: The Spaces of Pride & Prejudice.” Persuasions On-Line 27.2 (Sum. 2007). Dole, Carol M. “Jane Austen and Mud: Pride & Prejudice (2005), British Realism, and the Heritage Film.” Persuasions On-Line 27.2 (Sum. 2007). Ellington, Elisabeth H. “‘A Correct Taste in Landscape’: Pemberley as Fetish and Commodity.” Jane Austen in Hollywood. Ed. Linda Troost and Sayre Greenfield. 2nd ed. Lexington: UP of Kentucky, 2001. 90-110. Fraiman, Susan. “The Humiliation of Elizabeth Bennet.” Unbecoming Women: British Women Writers and the Novel of Development. New York: Columbia UP, 1993. 59-87. Gilbert, Sandra M., and Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination. New Haven: Yale UP, 1979. Goggin Joyce. “Pride and Prejudice Reloaded: Navigating the Space of Pemberley.” Persuasions On-Line 27.2 (Sum. 2007). Kaplan, Deborah. “Mass Marketing Jane Austen: Men, Women, and Courtship in Two Film Adaptations.” Jane Austen in Hollywood. Ed. Linda Troost and Sayre Greenfield. 2nd ed. Lexington: UP of Kentucky, 2001. 177-87. Kaplan, Laurie. “Inside Out/Outside In: Pride & Prejudice on Film 2005.” Persuasions On-Line 27.2 (Sum. 2007). Macdonald, Gina, and Andrew F. Macdonald, eds. Jane Austen on Screen. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Pride and Prejudice. Writ. Aldous Huxley and Jane Murfin. Dir. Robert Z. Leonard. Perf. Greer Garson and Laurence Olivier. MGM, 1940. Pride & Prejudice. Writ. Deborah Moggach. Dir. Joe Wright. Perf. Keira Knightley and Matthew Macfadyen. Focus, 2005. Roche, David. “Books and Letters in Joe Wright’s Pride & Prejudice (2005): Anticipating the Spectator’s Response through the Thematization of Film Adaptation.” Persuasions On-Line 27.2 (Sum. 2007). Seeber, Barbara K. “A Bennet Utopia: Adapting the Father in Pride & Prejudice.” Persuasions On-Line 27.2 (Sum. 2007). Troost, Linda V. “Filming Tourism, Portraying Pemberley.” Eighteenth-Century Fiction 18.4 (2006): 477-98. Troost, Linda, and Sayre Greenfield, eds. Jane Austen in Hollywood. 1998. 2nd ed. Lexington: UP of Kentucky, 2001. Wells, Juliette. “‘A Fearsome Thing to Behold’? The Accomplished Woman in Joe Wright’s Pride & Prejudice.” Persuasions On-Line 27.2 (Sum. 2007). Woloch, Alex. The One vs. the Many: Minor Characters and the Space of the Protagonist in the Novel. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2003.

|