|

In Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt,” fictional detective C. Auguste Dupin reads newspaper accounts of the investigation into the murder of Marie. From these he makes numerous deductions, but comes to no definitive solution. Reading the Gothic elements in Northanger Abbey alongside the tales of Edgar Allan Poe engenders a temptation to ferret out possible connections between them. Tantalizing clues lead to many conjectures but no definitive conclusions.

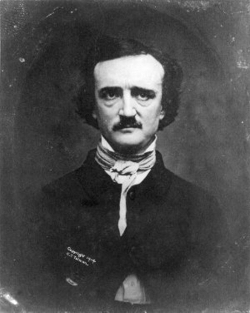

The playbill for the June 13, 1795, performance of the comic opera, The Maid of the Mill, at Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, announced that the role of Theodosia was played by Mrs. Arnold. It was her last performance in England. At the beginning of January Elizabeth Arnold and her nine year old daughter Eliza arrived in Massachusetts. Within months they appeared onstage. In Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography Arthur Hobson Quinn notes that Elizabeth Arnold appeared in The Mysteries of the Castle. According to Rictor Norton, “Miles Peter Andrews’s The Mysteries of the Castle [is] a dramatization based upon A Sicilian Romance, which also included characters drawn from The Mysteries of Udolpho” (124). Elizabeth Arnold played the role of a “romantic noblewoman” (4). At the end of the second act little Eliza “came out on the stage of the old Boston Theatre and sang the popular song of ‘The Market Lass’” (1). Thus began the theatrical career of the girl whose paternity is a mystery. At fifteen she married Charles Hopkins. Widowed in less than three years, she then married fellow actor David Poe, Jr. Their second child, Edgar, was born January 19, 1809.

“Here I am once more in this Scene of Dissipation & vice, and I begin already to find my Morals corrupted,” wrote Jane Austen on August 23, 1796, from Cork Street, London, to her sister Cassandra. “Once more,” she writes: so Austen had been in London before. How tempting it is to imagine her having seen Poe’s grandmother, Mrs. Arnold, in any of her roles, between 1791 and 1795: in The Woodman, A Rural Masquerade, Blue Beard, Orpheus and Eurydice, The Golden Pippin, The Castle of Andalusia, Bold Stroke for a Husband, and her last performance in England, The Maid of the Mill. We will never know. Yet Austen so vividly describes the “theatre scene” in Bath in Northanger Abbey that one hopes she had, indeed, seen Mrs. Arnold.

The theatre scene in Northanger Abbey marks an important turning point in the relationship between Catherine Moreland and Henry Tilney. Catherine, “[d]ejected and humbled, . . . had even some thoughts of not going with the others to the theatre that night,” but she did go, for “it was a play she wanted very much to see.” At first,

no Tilneys appeared to plague or please her; she feared that . . . perhaps it was because they were habituated to the finer performances of the London stage, which she knew, on Isabella’s authority, rendered everything else of the kind “quite horrid.” She was not deceived in her own expectation of pleasure; the comedy so well suspended her care, that no one, observing her during the first four acts, would have supposed she had any wretchedness about her. (92)

Henry arrives before the fifth act, and he and Catherine clear up the misunderstandings over the previously missed walking dates. It is during this encounter at the theatre that Henry is not “insensible” to Catherine’s honest “declaration” of apology, and her explanation for the prior mix-ups (94). Finally, “it was agreed that the projected walk should be taken as soon as possible; and, setting aside the misery of his quitting their box, she was, upon the whole, left one of the happiest creatures in the world” (95).

The Poes’ happiness in the theatre was short-lived. In October 1810 David Poe, Jr., disappeared. “Why he left them all is unknown, but by the age of twenty-five he had accumulated money problems, parental disapproval, drinking habits, bad reviews, a more successful wife, and children to support,” writes Kenneth Silverman in Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance (7). Eliza died on December 8, 1811, in Richmond, Virginia: “To Edgar, then nearly three, there apparently came a miniature portrait of Eliza, some of her letters, and her watercolor sketch of Boston harbor” (9). Edgar was taken in, but never formally adopted, by Frances (Fanny) and John Allan. Mr. Allan was in trade; his Richmond firm sold many items of merchandise, exported tobacco and flour, and imported foreign goods.

In October 1815 the Allans and Edgar arrived in London, where John Allan opened an office of the Allan and Ellis firm. George Dubourg worked as Allan’s assistant, and Edgar was sent to the school run by his relatives, the Misses Dubourg, at 146 Sloane Street, Chelsea. Edgar was there about two years. (Poe named a laundress, a witness in his tale, The Murders in the Rue Morgue, Pauline Dubourg.) The school was a few blocks from Henry Austen’s former home at 64 Sloane Street. Henry had relocated to 10 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, after his wife Eliza’s death. But in 1814 Henry returned to his old Chelsea neighborhood, to a house at 23 Hans Place, about a block west of the Sloane Street house. (The site now bears a marker proclaiming that Jane Austen lived there.) Jane stayed at Hans Place with Henry from October to mid-December 1815. She nursed him through his illness with the help of Mr. Haden, “the apothecary from the corner of Sloane St” (18 October 1815). Through a medical colleague of Haden, Jane Austen’s connection with the Prince Regent’s librarian, Rev. James Stanier Clarke, began, her visit to the official residence at Carlton House took place, and the dedication of Emma to the Prince Regent ensued. Yet, during these months in 1815, Austen would surely have continued her habit of walking, perhaps with her niece Fanny Knight, who joined her at Hans Place. It is tempting to imagine them encountering young Edgar or the Misses Dubourg on Sloane Street, or in the park nearby.

Across town from Henry’s place in Chelsea, Captain Charles Austen’s three little girls had been taken in by their maternal grandparents, the Palmers, “at 22 Keppel Street, Bloomsbury, where their aunt Harriet, the spinster of the family, could look after them,” reports Deirdre Le Faye in Jane Austen: A Family Record (216). They were Cassandra Esten, born 1808, Harriet Jane, born 1810, and Frances Palmer, born 1812. In September 1814 both their mother, Frances, and infant Elizabeth died on board ship within three weeks of the baby’s birth. Two months later, Austen wrote Fanny Knight from Henry’s at Hans Place,

I called in Keppel Street & saw them all, including dear Uncle Charles, who is to come & dine with us quietly to day.—Little Harriot sat in my lap—& seemed as gentle & affectionate as ever, & and as pretty, except not being quite well. Fanny is a fine stout girl, taking incessantly, with an interesting degree of Lisp and Indistinctness—and very likely may be the handsomest in time.—That puss Cassy, did not shew more pleasure in seeing me than her Sisters, but I expected no better;—she does not shine in the tender feelings. She will never be a Miss O’neal;—more in the Mrs Siddons line.— (30 November 1814).

A year later, on November 26, 1815, Austen wrote Cassandra from Hans Place that she and Fanny Knight

got to Keppel St . . . ., which was all I cared for—& though we could stay only a qr of an hour, Fanny’s calling gave great pleasure & her Sensibility still greater, for she was very much affected at the sight of the Children.—Poor little F[anny] looked heavy. . . . I hope we shall see Aunt H[arriet]—& the dear little Girls here on Thursday.— (26 November 1815)

Niece Cassy was at Chawton with her aunt Cassandra.

During their stay in London the Allans and Edgar lived at 39 and then at 47 Southampton Row, a few blocks southeast of Russell Square. By September 1816 Charles Austen was on half-pay, no longer at sea, and now also living at Keppel Street, just west of the square. Historian Dr. Susanne Terwey has examined Charles Austen’s diaries at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England. She informs me that each day he notes the wind and weather (not surprising for a navy man), and that he appears to be a good father, for he writes of taking walks with his children. He also often walks with his sister in law Harriet. It is tempting to imagine the Austens meeting the Allans and Edgar in Russell Square, certainly not a far walk for any of them. Cassy and Harriet would have been about Edgar’s age.

While in 1817 Edgar would have been home on weekends, he was a boarding student of Rev. John Bransby at Stoke Newington, then a village but now part of London. In his tale “William Wilson,” Poe writes, “My earliest recollections of a school-life, are connected with a large, rambling, Elizabethan house, in a misty-looking village of England. . . . At this moment, in fancy, I feel the refreshing chilliness of its deeply- shadowed avenues, inhale the fragrance of its thousand shrubberies, and thrill anew with undefinable delight, at the deep, hollow note of the church-bell, breaking, each hour, with sullen and sudden roar, upon the stillness of the dusky atmosphere in which the fretted, Gothic steeple lay imbedded and asleep” (338). (The character William Wilson is a regular John Thorpe, including the drinking at Oxford.) Poe’s description is a remembrance of those significant boyhood school days in England.

Might the Allan family have read Jane Austen? Fanny Allan was often not quite well. In the fall of 1817 she was at Cheltenham, taking the waters and the country air, as Austen and Cassandra had themselves previously done there. A year later she wrote, “My dear hubby, . . .be assured I embrace every opportunity that offers for takeing [sic] air and exercies [sic] but at this advanced seasons [sic] of the year we cant expect the weather to be very good”(qtd in Quinn 78). Perhaps in inclement weather she was a reader. In December 1817 Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, by Bloomsbury neighbor Charles Austen’s deceased sister, were published. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, itself less than a year old, printed a review in May 1818.

We are happy to receive two other novels from the pen of this amiable and agreeable authoress, though our satisfaction is much alloyed, from the feeling, that they must be the last . . . (T)he delightful writer of the works now before us, will be one of the most popular of English novelists, and if, indeed, we could point out the individual who, within a certain limited range, has attained the highest perfection of the art of novel writing, we should have little scruple in fixing upon her. She has confined herself, no doubt, to a narrow walk. She never operates among deep interests, uncommon characters, or vehement passions. The singular merit of her writings is, that we could conceive, without the slightest strain of imagination, any one of her fictions to be realised in any town or village in England, (for it is only English manners that she paints,) that we think we are reading the history of people whom we have seen thousands of times, and that with all this perfect commonness, both of incident and character, perhaps not one of her characters is to be found in any other book, portrayed at least in so lively and interesting a manner. She has much observation,—much fine sense,—much delicate humour,—many pathetic touches,—and throughout all her works, a most charitable view of human nature, and a tone of gentleness and purity that are almost unequalled. (257-58)

Fanny Allan was a refined, genteel Southern lady. Had she or Mr. Allan seen this review either might well conclude these novels of “delicate humour” and “tone of gentleness and purity” would be just the thing to read for Fanny Allan and, perhaps, young Edgar, as well.

Alas, of all the sixty-three diaries of Charles Austen at the National Maritime Museum, between 1815 and 1852, the diary for 1818 is missing. Would that we could read his entries about Northanger Abbey. It is safe, however, to assume he read both of his late sister’s novels, as he had read the others. Perhaps Fanny Allan did too, and perhaps Edgar, now nine, read Northanger Abbey at some time home from school, or it may have been read aloud.

What might Edgar have thought about Catherine’s mother who, “instead of dying in bringing [her] into the world, as any body might expect, . . . still lived on” (13), and Catherine’s home life where “[t]here was not one family among their acquaintance who had reared and supported a boy accidentally found at their door—not one young man whose origin was unknown” (16)? Might Edgar have seen himself? Chapter Two brought “[a] thousand alarming presentiments of evil” and “[c]autions against the violence of such noblemen and baronets as delight in forcing young ladies away to some remote farm-house” (18). Would Edgar have identified with Catherine, a young person in the care of a couple called the Allens, just as he was? In her first venture to the Upper Rooms at Bath, Catherine “could not relieve the irksomeness of imprisonment by the exchange of a syllable with any of her fellow captives” (22). And Catherine had not yet arrived at Northanger Abbey! “Gothic stories—supernatural tales set, often, in medieval ruins—had been popular for decades. They were fun to write on a rainy day, as Mary Shelley had discovered, and even more fun to parody, as Jane Austen found out (both Frankenstein and Northanger Abbey were published in 1818, when Poe was in England),” writes Jill Lepore.

In 1820 Charles Austen married his sister-in-law Harriet Palmer. At the beginning of the year, the Allans and Edgar returned to Virginia. Had he read Northanger Abbey by then? One can only guess. Of one thing we can be certain: he did read Blackwood’s Magazine throughout his life, as he reports in the many reviews he wrote of the works of other authors. In addition to reviews, Blackwood’s also published horror stories. Reviewing Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Twice-Told Tales in 1847, Poe wrote,

For Beauty can be better treated in the poem. Not so with terror, or passion, or horror, or a multitude of other such points. And here it will be seen how full of prejudice are the usual animadversions against those tales of effect many fine examples of which were found in the earlier numbers of Blackwood [the first issue of which was April 1817, when Edgar was in England]. The impressions produced were wrought in a legitimate sphere of action, and constituted a legitimate although sometimes an exaggerated interest. They were relished by every man of genius: although there were found many men of genius who condemned them without just ground. The true critic will but demand that the design intended be accomplished, to the fullest extent, by the means most advantageously applicable. (573)

Perhaps it was in Northanger Abbey that Poe found an author who accomplished her intended design to the fullest extent.

Apparently never published in Blackwood’s, Poe wrote a satirical piece entitled “How to Write a Blackwood Article.” The narrator, Psyche Zenobia, is counseled by Mr. Blackwood himself:

“Sensations are the great things after all. Should you ever be drowned or hung, be sure and make a note of your sensations—they will be worth to you ten guineas a sheet. If you wish to write forcibly, Miss Zenobia, pay minute attention to the sensations. . . . The first thing requisite is to get yourself into such a scrape as no one ever got into before . . . and if you cannot conveniently tumble out of a balloon, or be swallowed up in an earthquake, or get stuck fast in a chimney, you will have to be contented with simply imagining some suitable misadventure. . . .” Here I assured him I had an excellent pair of garters, and would go and hang myself forthwith. (281-82)

Miss Zenobia then goes on to write the story of her beheading by the minute hand of a church steeple clock. This is a delicious piece of writing that Austen might have appreciated. In Northanger Abbey she wrote forcibly, and she did pay minute attention to the “awful sensations” of Catherine, whose “heart fluttered, . . . knees trembled, and . . . cheeks grew pale” when she found the imagined “precious manuscript” in the black cabinet (169).

At the close of 1832 the first American edition of Northanger Abbey and Persuasion was published in Philadelphia by the firm of Carey & Lea. They had had great success with the publication of the novels of James Fenimore Cooper and Sir Walter Scott, and Poe asked the firm, unsuccessfully, to publish him. With the addition of Blanchard as a partner, and the retirement of Carey, the firm of Lea & Blanchard, in 1839, finally published Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, including twenty-five of Poe’s tales. Poe was then living in Philadelphia with his wife and cousin, Virginia, and her mother, Maria Clemm. He must have been aware of his publisher’s Northanger Abbey.

Austen and Poe had shared tastes in poetry and novels. Both were fans of Sir Walter Scott. Poe refers to “that purest, and most enthralling of fictions, the Bride of Lammermuir [sic] . . . the master novel of Scott, . . . the magic tale of which Ravenswood is the hero” (Essays 167). Austen wrote to her niece Anna Austen, “Walter Scott has no business to write novels, especially good ones.—It is not fair.—He has Fame & Profit enough as a Poet, and should not be taking the bread out of other people’s mouths” (28 September 1814). Poe, even more so than Austen, was an impoverished writer. Of the poets Austen admired, Poe comments on the “old-school manner of Cowper” (Essays 446). He declares, “Crabbe is a more noble poet than Milton” (Essays 695). It was Crabbe, one recalls, whom Austen joked of marrying (21 October 1813). Poe also comments on women authors of Austen’s day and later. He writes that Edward Bulwer Lytton is “generally inferior to Scott, . . . Miss Burney, [and] . . . the author of ‘Jane Eyre’” (Essays 1452). Austen wrote to Anna, “I have made up my mind to like no Novels really, but Miss Edgeworth’s, Yours & my own” (28 September 1814). Poe, however, criticizes Maria Edgeworth’s use of the word fashion: “Miss Edgeworth seems to have had only an approximate comprehension of ‘Fashion,’ for she says: ‘If it was the fashion to burn me, and I at the stake, I hardly know ten persons of my acquaintance who would refuse to throw on a faggot’” (Essays 1307). Do we here see shades of Henry Tilney’s criticism of Catherine’s use of the word nice: “‘Oh! it is a very nice word indeed!—it does for every thing’” (108)?

Other connections between Austen and Poe suggest she may have been an influence. That mistress of mystery writers, P.D. James, alleges in Talking About Detective Fiction that Poe’s creation “detective Chevalier C. Auguste Dupin, was the first fictional investigator to rely primarily on deduction from observable facts” (33). Dupin is featured in Poe’s tales “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” “The Purloined Letter,” and “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt.” And yet, did not Austen’s Northanger Abbey characters already rely primarily on deduction from observable facts? Could they have been an inspiration for the creation of Dupin?

Henry Tilney is an acute observer, particularly of Catherine. At their first meeting, Henry credits his perceptions: “‘I see what you think of me’” (26). Henry comprehends Catherine and Eleanor Tilney’s confusion about the very shocking something that will soon come out of London—not a riot, but a new publication. He understands Catherine “‘perfectly well’” (132). Henry discerns Catherine’s preconceived ideas of the abbey. Having discovered that Catherine has been to his mother’s room, and “[a]fter a short silence, during which he had closely observed her,” Henry perceives her conclusion about General Tilney: “‘And from these circumstances,’ he replied, (his quick eye fixed on her’s), ‘you infer perhaps the probability of some negligence—some—(involuntarily she shook her head)—or it may be—of something still less pardonable’” (196). While Catherine reads the letter from her brother James, “Henry, earnestly watching her through the whole letter, saw plainly that it ended no better than it began” (203). “Henry began to suspect the truth” (204) of the broken engagement between James and Isabella Thorpe.

In Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue, the unnamed narrator admires the “peculiar analytic ability” of Dupin, and together they go about “seeking . . . that infinity of mental excitement which quiet observation can afford” (401). The narrator relates his astonishment at Dupin perceiving his thoughts by careful observation. “‘Tell me, for Heaven’s sake,’ I exclaimed, ‘the method—if method there is—by which you have been enabled to fathom my soul in this matter’” (402). Dupin has observed the narrator’s walk, the focus of his eyes, the brightening up of his countenance, the murmured word, and “the character of your smile which passed over your lips” (404). Like Henry Tilney, Dupin discerns another’s thoughts by close observation.

The rest of the tale details Dupin’s deductions from the evidence to solve the murders which have baffled the police. “Nevertheless, that he failed in the solution of this mystery, is by no means that matter for wonder which he supposes it; for, in truth, our friend the Prefect [of Police] is somewhat too cunning to be profound” (431). Perhaps, then, Catherine, lacking cunning, is an even better detective than Henry: “guided only by what was simple and probable, it had never entered her head that Mr. Tilney could be married; he had not behaved, he had not talked, like the married men to whom she had been used; he had never mentioned a wife, and he had acknowledged a sister. From these circumstances sprang the instant conclusion of his sister’s now being by his side” (53). Lacking cunning, Catherine simply deduces General Tilney’s probable crimes toward his wife from the evidence: his not walking in her beloved gloomy grove, Eleanor’s not answering an inquiry about Mrs. Tilney’s dejection of spirits, the General’s dissatisfaction with his wife’s portrait, his reluctance to show Catherine her room, his solitary rambles, his pacing the drawing-room, and his staying up for hours at night.

Dupin could have come to the same supposition as Catherine: that Mrs. Tilney might be imprisoned in a cell in the abbey, or even murdered. “Down that stair-case she had perhaps been conveyed in a state of well-prepared insensibility!” (188). Catherine finds no clues when she finally inspects Mrs. Tilney’s room: “No: whatever might have been the General’s crimes, he had certainly too much wit to let them sue for detection” (194). When Henry surmises her suspicions he asks, “‘What have you been judging from? . . . Consult your own understanding, your own sense of the probable, your own observation of what is passing around you’” (197)—exactly, of course, what she had been doing. Henry’s observations about being English and Christian, about their education and their laws, about voluntary spies and the roads and newspapers making “‘everything open,’” are not very convincing. What do they have to do with imprisonment and murder? When Henry comes to Fullerton, and to his senses, “Catherine, at any rate, heard enough to feel, that in suspecting General Tilney of either murdering or shutting up his wife, she had scarcely sinned against his character, or magnified his cruelty” (247). In Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Roderick Usher does, indeed, convey his sister Madeline, in a state of insensibility, down that staircase, to be entombed in a vault under the building, and thereby murdered.

The evidence for Poe’s reading of Northanger Abbey is circumstantial. He never mentions Austen in his many essays and reviews of European and American authors. The silence, in fact, is deafening. Did Poe have so much wit as to prevent detection? Like the evidence in his tale “The Purloined Letter,” there are no clues in plain sight. Guided only by what is simple and probable, however, we may venture to deduce that the shadows of Northanger Abbey did reach Poe, if not as a boy in England, then surely as a man in America. Works Cited Austen, Jane. Jane Austen’s Letters. Ed. Deirdre Le Faye. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1995. _____. Northanger Abbey. Ed. R.W. Chapman. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 1969 James, P. D. Talking About Detective Fiction. New York: Knopf, 2009 Le Faye, Deirdre. Jane Austen: A Family Record. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2004. Lepore, Jill. “The Humbug: Edgar Allan Poe and the Economy of Horror.” The New Yorker Online 27 April 2009. http://www.newyorker.com/arts/critics/atlarge/2009/04/27/090427crat_atlarge_lepore?pri Norton, Rictor. Mistress of Udolopho: The Life of Ann Radcliffe. London: Leicester UP, 1999. Poe, Edgar Allan. Essays and Reviews. New York: Library of America, 1984. _____. Poetry and Tales. New York: Library of America, 1984. Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1998. Rev. of Northanger Abbey and Persuasion. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine n.s.2 (May 1818): 453-55. Rpt in Northanger Abbey. Ed. Claire Grogan. 2nd ed. Peterborough: Broadview P, 2004. 257-58. Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. New York: Harper, 1991.

|