|

“what separates the casual Jane Austen fan from the aficionado—she finds her way here to the world’s most immersive Austen experience”: so reads a small print ad published in a handful of newspaper travel sections during the summer of 2013 (Karpel). Although the advertisement purportedly announced the opening of a fictitious vacation destination where you, the ultimate Austen fan, can “find your Mr. Darcy,” it in fact promoted the premier of Jerusha Hess’s 2013 film Austenland. As this none-too-subtle ad indicates, a major satirical target of the film (and the 2007 novel by Shannon Hale) is the escapism of the ardent Austen fan. As exemplified by Keri Russell’s character, Jane Hayes, the “aficionado” voraciously consumes all things Austen, indicated by (among other things) the life-size cardboard cutout of Colin Firth’s Darcy in her apartment. Introverted and even slightly misanthropic, Jane surrounds herself with Austen’s world to avoid reality, from dead-end jobs to dead-end boyfriends.

The stereotype of the escapist Janeite—and, by extension, the perceived disconnect between Austen’s novels and the twenty-first-century world—pervades the media and haunts many of our students as they enter our classrooms. As Olivera Jokic’s essay in this volume astutely argues, some students reject Austen outright because her novels seem only concerned with romantic narratives that end in marriage between upper-class people, or with issues that many students dismissively call “First World problems,” a term that suggests the absurdly minor inconveniences that stymie members of the spoiled upper classes.1 Other students, many of whom fall into the above category of “Austen aficionado,” have a hard time seeing beyond their admiration of Darcy’s (or Colin Firth’s or Matthew McFadyen’s) proposal scenes. Marcia McClintock Folsom describes the obstacles to teaching Austen in this way: for many students, “Austen’s legacy is so well known that using the words ‘Jane Austen’ is sufficient to evoke a whole world, and . . . no further comment is needed to know what world is being described” (“Privilege”). To many new readers, Austen’s world seems to revolve primarily, if not solely, around fairytale plots of romance and privilege.

As countless readers, critics, and teachers acknowledge, however, the marriage plots of Austen’s novels also necessarily frame broader sociopolitical issues from her time, particularly those related to the limited volition of nineteenth-century women. As I will show in this essay, in Emma, Austen links her titular heroine’s failed acts of agency and feelings of isolation to those faced by other non-dominant groups, including those who are non-English and poor. Yet even if students are able to see the proto-feminist energies of a novel like Emma, it is nevertheless difficult for many to overcome the disconnect that they perceive between Austen’s early nineteenth-century world—replete as it is with lavish balls, country walks, and carriage rides—and their own experiences in the twenty-first century. This essay suggests that one way to address these pedagogical challenges is to incorporate service-learning activities into the Austen curriculum. Such activities can help students re-evaluate the biases that they knowingly or unknowingly espouse with regard to Austen and her novels, while they can also make more vivid the dynamic points of connection between Austen’s early nineteenth-century Britain and our own historical moment. Indeed, such an experiential approach to interpreting Austen’s novels can help new readers access the complexity of her fictive worlds as they also locate a more active role within their own immediate and future academic and social communities.

Although pedagogical strategies grounded in service-learning can complement any Austen text by emphasizing the underlying socioeconomic concerns of her works, I will focus here on using this model to teach and interpret Emma. In some ways, Austen’s fourth published novel forges the most easily accessible connection to community work. Unlike other economically insecure Austen heroines, Emma Woodhouse, as a member of the landed gentry, has the financial resources—as well as an implicit societal obligation—to serve others in various capacities. Devoney Looser has noted that the novel “models the way elite women should wield power over less-privileged females through its protagonist’s mistakes” (101); I wish to build upon Looser’s insightful claim by considering the ways in which the novel interrogates Emma’s social responsibility to the broader Highbury community, including those impoverished and ostracized men, women, and children who live in the liminal space beyond the town’s center. In addition, the novel’s setting registers concerns about the changing socioeconomic landscape of England. Laura Mooneyham White puts it this way: “The world of social flux is accurately rendered . . . in Emma, where almost every character is rising or falling or at least trying to rise or trying not to fall” (41). This volatility resonates with present-day students, many of whom face similar uncertainty upon graduation. While not exact correlations, these comparisons allow students to forge illuminating connections between their assigned reading and service work.

A service-learning model of studying Emma ultimately reveals to students a new and innovative reading of the novel, one that helps them analyze how Austen uses Emma to represent the plight of characters who have no discernible place within Highbury. I argue that by demonstrating the ways in which her heroine fails to assume her role as benefactress to those around her, Austen ironically links the privileged Emma to the impoverished outsiders that punctuate the novel’s landscape, from the poor cottagers whom Emma fails to help in any substantive way, to the gypsies that Harriet encounters, to the poultry-house robbers that frighten Mr. Woodhouse and facilitate the resolution of the marriage plot. Combined with Emma’s failures with Harriet, Miss Bates, and Jane Fairfax, these incidents demonstrate the ways in which Emma increasingly finds herself a foreigner in her own community.2 Emma’s challenge connecting with others in Highbury becomes all the more significant when read alongside a discussion of students’ own service experiences. By discussing these issues in tandem, new readers of Austen can more readily understand the complex questions that the novel poses about the possibility—in both Austen’s time and our own—of achieving social justice for those who have limited economic, political, or social agency.

In what follows, I begin by considering the ways in which the service-learning integrated literature course offers a reciprocally beneficial platform for both fields of inquiry. I then turn to an examination of how Austen’s novels, and Emma in particular, demonstrate this reciprocal relationship. Indeed, reading Emma via the framework of civic engagement allows us to trace Emma’s increasingly fractured place within Highbury society, while it also enables students to understand better how Austen’s novel engages with her world and ours. This approach relocates our focus from the romantic myth of Austenland, instead retraining our critical gaze to reveal the significant connections between “the streets” of Highbury and those within and beyond our campuses.

Locating “the street” in the literary classroom

At most college campuses across the United States, clubs, groups, and offices that advocate for various types of service activities have become increasingly visible. Of this trend, Caryn McTighe Musil observes, “There has been a quiet revolution occurring in the academy over the last two decades. Civic concerns have achieved new visibility alongside the traditional academic mission of higher education” (4).3 While these service activities are often referred to interchangeably as “volunteering,” “community service,” or “service-learning,” I suggest that we might productively employ the phrase “civic engagement” to encapsulate the above-mentioned terms. Jean Y. Yu helpfully defines civic engagement as “the actions of informed individuals and collectives to respond to the needs created by systems of social injustice in the communities in which they live and work. . . . [It] must be requested or approved by communities themselves, and executed in collaboration with community participants” (160). Here, Yu articulates civic engagement’s emphasis on multiple levels of social justice, from the reciprocal partnership with community agents, to the theoretical and political aims attendant to ethical practices. As a sub-category of civic engagement, then, we can distinguish service-learning from volunteerism or the phrase “community service” because of its academic grounding; “like any test, paper, or research project, the service learning experience must be integral to the syllabus and advance the students’ knowledge of the course content” (Jay 255).

Although service-learning courses are especially prominent in fields like the social sciences, they can provide fruitful and effective formats for classes in literary studies as well. For instance, Mary Schwartz has recently argued that “the poetics of language draws students into imagined worlds that help them to question their own worlds and to begin to extend themselves to others” (988-89). Schwartz’s point helps us rethink the image of the Austen aficionado with which this essay opened; rather than fostering a disconnect from real-life issues, such immersive reading practices might in fact create in readers an awareness of and sympathy for other unfamiliar situations as well as skepticism towards the status quo of their own surroundings. Likewise, Anna Sims Bartel notes that the literary student’s ability to understand narrative as construct, to analyze story rigorously, helps her critique the common narrative of a given demographic of people or place (86). Far from conflicting, the intellectual work of literary study is well suited for experiential work.

Still, there are aspects of service-integrated literary work that require careful consideration and caution. Laurie Grobman has importantly expressed two concerns with such integration: first, that service-learning “can too easily encourage narrow interpretations of literature to fit or explain real-world situations, especially those related to race, class, gender, or other categories of difference” (129-30). Second, Grobman notes that “because service learning is for many students their first real-world encounter with some of the nation’s profound social ills, it can be difficult for them to avoid seeing themselves as saviors despite the emphasis on mutual learning” (130). As I will discuss in more detail below, Emma presents characters and situations that critique or undermine the “savior complex,” an effect of what Ellen Cushman calls the “liberal do-gooder stance” (332) that many students experience when they begin service-learning activities. In fact, as students in a service-integrated course trace the strategies that Austen uses to dismantle Emma’s own pretentions of do-gooder glory, they must also recognize that service-learning is not simply a system in which they, the privileged, smart students, sweep in to save the “less fortunate.”

One key challenge, then, is helping students question both the motivations that inform, as well as the effects that result from, community engagement practice. To do so, students not only consider service activities from their own perspective, but they also imagine themselves in the role of the service partners and the population with whom they will work. As Linda Flower suggests, through such acts of “intercultural inquiry,” students can “[seek] rival readings of an issue”; as a result, this process has “the potential to transform both the inquirers and their interpretations of problematic issues in the world” (qtd. in Grobman 134). To emphasize both the rival readings—the benefits and the risks—of a practice that brings together people from often divergent life experiences, I find that it is helpful to use the hyphenate “service-learning,” in both course descriptions and on the first day of class, to demonstrate the tensions inherent to its practice. On one level, the links between “service” and “learning” are “interdependent and dynamic” (Cress et al. 8). Yet in addition to stressing the connections, the hyphen in “service-learning” underscores some of the practice’s intellectual and practical challenges. Rather than “simply ‘celebrating diversity’” (Jay 256), an act that dismisses important distinctions among students, professors, and service sites, service-learning participants must “learn to critique the assumptions they bring to the encounter and to respect the different virtues and assets each has to offer” (257). In so doing, we allow for a multiplicity of perspectives and norms: we “proceed more beneficially when differences are accepted as assets rather than obstacles” (257).

Crucial to intercultural inquiry is a pedagogy that acknowledges the complexity involved in connecting people from divergent backgrounds. Indeed, while many service-learning teachers use the rhetoric of harmony and collaboration when discussing service partners, I find compelling and significant Paula Mathieu’s observation that, in some cases, the word “community” denies the challenges that our students and our service partner organizations face on a daily basis (xii). Instead, following Mathieu, we might productively use a more colloquial, and perhaps more accurate, term: “the street.” Mathieu writes that “‘the street’ . . . may refer to a specific neighborhood, community center, school, or local nonprofit organization. Like all the other possible terms (such as community, sites of service, contact zones, outreach site, etc.), street is a problematic term, but one whose problems, I hope, help illuminate the difficulties associated with academic outreach” (xii).

While terms like “community” and “contact zones” all promote a rather abstract sense of place, thinking of service-learning as focused on the street offers a significant “spatial metaphor for the destination of academic outreach and service learning” (Mathieu xiii). In recognizing these tensions and the role of place, our classes can have an important conversation about the distinction between classroom or campus life and life “out there.” This approach allows us to “collapse harmful dichotomies that traditional university knowledge espouses: literary/vernacular; high culture/low culture; literature/literacy; objective/subjective; expert/novice” (Cushman 335). Considering “the street” in service-learning endeavors helps students recognize their assumptions and fears about the supposed dangers “out there” and also encourages them think critically about the space and activities of the campus.

Critiquing “the street” in Highbury

Despite the increasing presence of community engagement initiatives, there are two particular obstacles that confront teachers who wish to pair service-learning with an Austen text or class. First, while service-integrated pre-twentieth-century literature courses are rather rare, available pedagogical scholarship on the practice is even less common.4 As I prepared to teach a service-integrated class on Austen, I found myself sympathizing with Shakespearean scholar Matthew C. Hansen, whose work also speaks for Austen service-learning pedagogy: “Almost no published scholarship exists on how courses on Shakespeare—a staple of nearly every college English department—might engage with the community through service-learning that provides a genuine community benefit while simultaneously deepening undergraduate students’ engagement with and understanding of Shakespeare” (177). Like Shakespeare’s significant place in the Western canon and classroom, Austen’s pervasive presence in the Western cultural imagination provides both points of access and, as mentioned in the introduction, myriad obstacles for twenty-first-century teachers of her novels, as many students arrive, whether gleefully or reluctantly, with certain assumptions about Austen and her novels. The second challenge becomes apparent from institutional data: studies by Ostrander and Portney and others have suggested that particular demographic groups—among them, women, persons of color, and those who are low-income—are far less frequently represented in civic engagement activities.5 While this under-representation is certainly troubling for all institutions, it is even more troubling at large, public institutions like my own that focus on teaching underserved student populations. Although these statistics are alarming, they offer an impetus for universities to confront the absence of diverse and committed participants in service activities. Indeed, for colleges that primarily serve the demographics listed above or for those that wish to address this imbalance, it is imperative to create a flexible and sustainable service-learning curriculum that encourages students to complete their experiential coursework.

My first attempt to bridge these gaps came in spring 2013, with a semester-long undergraduate senior seminar entitled “Jane Austen, Satire, and Society: A Service-Learning Course.” In this course, students read all of Austen’s major novels as well as Sanditon and selections from her juvenilia. In addition to primary and secondary readings, part of students’ coursework involved at least twenty hours of community engagement work, which included direct service activities like after-school and creative writing tutoring at a nonprofit literacy organization, 826LA; capacity building work like sorting food and clothing donations at a local community resource agency, MEND (Meeting Each Need with Dignity); and digital service activities in the form of editing and correcting the OCR (optical character recognition) of digitized rare eighteenth-century books via 18thConnect (while not immediately apparent as a service activity, this sort of transcription will ultimately make these texts accessible for the visually impaired, as current adaptive technology requires such OCR capability).6 Students also had the opportunity to locate an alternative service site either on or off campus that connected with their interests and availability. I used this approach for two reasons. First, although “matching students to projects can be labor-intensive,” like Schwartz I find that “students who exercise agency in their community adjust more creatively to the partnership setting than do those who are assigned a placement” (990). Second, as mentioned above, one reason that many non-traditional and non-white students do not participate in service activities involves their financial and logistical abilities to do so; allowing students to tailor their activities to their own needs empowered them to be more likely to participate fully in such experiential activities.

Perhaps the most important practice throughout a service-integrated class is to design and implement a sustained system of active reflection activities.7 To encourage students to consider the social dimensions of Austen’s novels even before their service activities began, I implemented a weekly online forum for students to discuss ideas and experiences related to class, service, and their own and their peers’ work; unlike traditional handwritten journals, the online component of the class helps students engage with one another more readily and offers a higher level of accountability, keeping students posting in real-time with their experiences. (Most schools have secure platforms like Blackboard or Moodle; Google Groups is another useful option to encourage discussion in an online, yet not fully public, Internet forum.) Early in the semester, as students were beginning Sense and Sensibility, I prompted the class to compare their initial understanding of Austen’s social awareness with those found in critics’ arguments. For instance, in the second week of class, students read excerpts from Marilyn Butler’s seminal Jane Austen and the War of Ideas. On our discussion board, I summarized a main claim of Butler’s work: although Butler admits that Austen “looks in her last few years like a social commentator” with novels like Mansfield Park (1814), Emma (1816), and Persuasion (1817), she proposes that Austen’s seemingly progressive representation of characters like Fanny, William, and Susan Price merely critiques their higher-ranking cousins. For Butler, “This was no more a revolt on behalf of the underprivileged than it was a revolt on behalf of women” (xliv).

I asked students to evaluate and respond to Butler’s argument via their initial impressions of Sense and Sensibility and Mansfield Park. While some students’ posts agreed that these novels before Emma lack social awareness, others argued that the texts’ focus on female agency and on issues like the Dashwood sisters’ lack of inheritance or legal claims to their father’s estate suggests a keen awareness of at least certain social problems, especially those faced by women. Likewise, our class discussed inequalities that various groups still face: students were quick to note that women receive less financial compensation than men for the same work; that poor children are less likely to excel in school; and that many states have official racial profiling protocols as part of their legal systems. I paired this discussion with two recent articles by Susan C. Greenfield published in popular online sources, both of which connect Austen to present-day issues: child poverty and the Violence Against Women Act. As many students in my class are of non-white descent and from low-income backgrounds, these discussions were particularly engaging and important to them. Students began to see that while Austen’s world may permit fantasy visions of Firth’s Darcy, it also reveals complex social and economic inequalities found in her time and our own.

We began reading Emma about halfway through the semester when most students had just started their service coursework; this confluence helped build on earlier class discussions of Austen’s street while it also immediately confronted students with the savior complex that Emma so keenly exemplifies. As Marcia McClintock Folsom has observed, the character of Emma—“handsome, clever, and rich” (Austen 3)—poses almost immediate challenges to student readers: “The opening page, with its famous first sentence, can repel students whose egalitarian values are affronted by Emma’s obvious privileges. . . . How can a teacher help students understand Emma’s position as a woman with power and Emma as a person whom readers love even when they behold her arrogantly interfering with other people’s lives?” (“Introduction” xvii, xxiv).

As mentioned above, I suggest that there are a handful of key scenes that empower students to recognize the tension between Emma’s perception of herself (handsome, clever, and rich) and her increasing psychic distance from the changing Highbury community. The first is an often-overlooked passage in which Emma and Harriet perform a “charitable visit” to “a poor sick family, who lived a little way out of Highbury” (89). Just after the famous moment in which Emma explains to Harriet that she refuses to marry because of her financial independence, Emma and Harriet approach and enter the cottage. Using free indirect discourse, Austen writes,

Emma was very compassionate; and the distresses of the poor were as sure of relief from her personal attention and kindness, her counsel and her patience, as from her purse. She understood their ways, could allow for their ignorance and their temptations, had no romantic expectations of extraordinary virtue from those, for whom education had done so little; entered into their troubles with ready sympathy, and always gave her assistance with as much intelligence as good-will. In the present instance, it was sickness and poverty together which she came to visit; and after remaining there as long as she could give comfort or advice, she quitted the cottage with such an impression of the scene as made her say to Harriet, as they walked away, “These are the sights, Harriet, to do one good. How trifling they make every thing else appear!” (93)

Of course, Emma almost immediately forgets the plight of the poor cottagers when she and Harriet encounter Mr. Elton on their walk home, and Emma’s desire for matchmaking soon surmounts any interest in poor relief.

This moment can either encourage or resist readers’ sympathy for Emma, creating a tension that warrants intercultural inquiry. Austen’s use of free indirect discourse, which fosters an indeterminacy of authorial or narratological judgment, encourages students to debate among themselves the meaning of this passage, while it also helps them to reflect on how their different cultural backgrounds might inform their understanding of this moment. For instance, if students contrast Emma’s behavior with Mr. Elton’s total obliviousness to the cottagers’ plight, they might discover an admirable quality in the novel’s heroine; as Laura Mooneyham White argues, because “Emma’s sense of noblesse oblige is genuine . . . , [it] sets her above the clergyman whose charity is a masquerade” (39). For students who see clergy members as being guiding forces in moral and ethical behavior, this moment can elevate Emma as it demotes Elton.

At the same time, other students might read this moment as indicating Emma’s sheer obliviousness to her community as a result of her own savior complex; the challenge of this reading is to help students consider to what extent Emma herself might be enforcing and encouraging the inequality that she perceives. I invite my students to analyze how Austen’s use of free indirect discourse, and its ability to satirize its targets, might indicate how Emma’s often-condescending attitude towards Harriet and others in fact forces her into a position of marginalization. For instance, although the passage notes that “Emma understood their ways,” readers know that one of Emma’s continual mistakes is assuming that she best understands people’s motives. Read this way, we might interpret the narrator to be representing Emma’s often self-satisfied view of her public persona. Likewise, I ask my students, “What real ‘relief’ can Emma offer these cottagers through her visit?” Students are quick to note that Emma eventually sends some healthful soup back with one of the cottagers’ daughters. This act is generous, to be sure; but the relief is, if occurring at all, quite temporary. If we read these moments alongside Emma’s almost instantaneous forgetfulness about the entire situation, we can see Austen’s narrator using free indirect discourse to ironize Emma’s abilities as an effective patroness. Rather than showing Emma’s integral role in the streets of Highbury, this moment indicates her limited relevance. Whether cultivated or accidental, Emma’s savior complex distances her from those in her community, from the poor cottagers to Harriet, Jane Fairfax, and the Bates family.

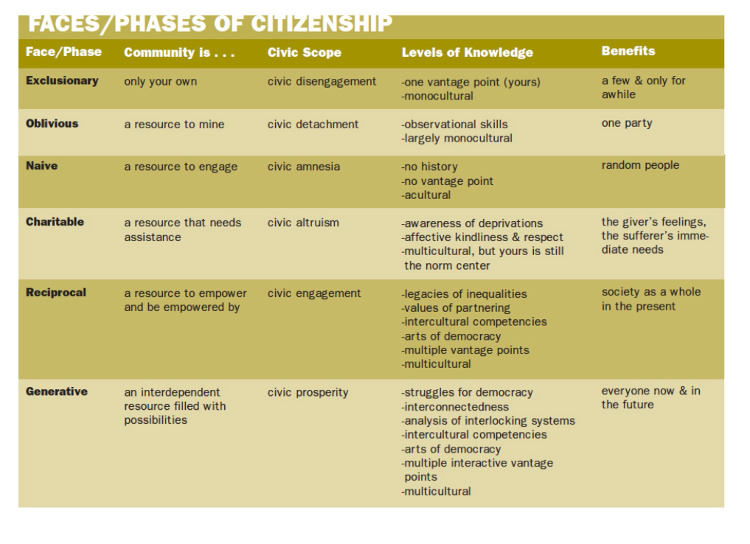

Reading this passage closely allows students to deconstruct the notion of being a savior for others through service. When I asked students to compare their service activities to a handful of the characters or scenes in Austen’s novels and to categorize both using Musil’s service spectrum, which ranks students’ understanding of their service involvement from “exclusionary” and “naïve” to “reciprocal” and “generative” (see figure 1), the majority of students used Emma’s character—both her good and her problematic intentions—as a touchstone for their own experiences.8 One student, Laura, reflected that as she began her after-school tutoring service work at 826LA, her mindset “was very much like Emma’s. . . . I had a recurring and self-justified thought that ‘at least I’m doing something, which is much more than other people of my generation can say.’”9 For Laura, linking Emma’s behavior with her previous service activities helped her create a more active, less complacent, and, as Musil would categorize it, less “naïve” model of civic engagement, an idea that many of her classmates echoed.

At the same time, students were able to understand that the narrator’s opening description of Emma belies her increasing exclusion from the majority of the Highbury community. Anna, another student who was very attentive to Emma’s class snobbery, argued, “Emma . . . see[s] the cottage as a separate zone in which her scheme for matchmaking can take place. It is not her land. It is the OTHER’S land. . . . The narrator says that Emma ‘enters into their troubles.’ As much as she focuses on their troubles, she has not seen them as her own, and thus there is a major lack of interconnectedness.” Anna’s comments here emphasize her awareness of the divide between those who serve and those who are recipients of such service. This perspective helped Anna recalibrate her perspective on her own service activities: “While working at 826LA I was not seeing the children as deprived or ‘ignorant,’ as Emma describes her charity cases, but instead as fortunate. They are being empowered by attending 826LA. They are able to use their imaginations and think about school subjects in a new and fun way that they cannot experience in class.” Rather than seeing the students she worked with via a deficit model, Anna was able to identify with the students themselves and imagine herself in their place.

Anna’s comments demonstrate that there is ample room in Emma to discuss the construction of “otherness” as it relates to power; Emma not only treats the poor cottagers as “others” but in the process does not enhance her own superiority; instead, she distances herself from her community. The process by which Austen increases Emma’s alienation from Highbury becomes clearer when students begin to see how the novel problematizes matters of race. Emma provides two such passages that teachers can effectively integrate in a sustained discussion of otherness. The first moment, at the end of Volume II, arises when Jane Fairfax compares her potential role as governess to “‘the sale—not quite of human flesh—but of human intellect’” (325). Mrs. Elton, perhaps misunderstanding Jane’s reference to prostitution (579 n. 2), immediately links Jane’s description to the slave trade; she attempts to vindicate Jane’s intended employer and her own relations by proclaiming, “‘[I]f you mean a fling at the slave-trade, I assure you Mr. Suckling was always rather a friend to the abolition’” (325). Jane attempts to separate the explicit comparison by demurring, “‘I was not thinking of the slave-trade . . . ; governess-trade, I assure you, was all that I had in view; widely different certainly as to the guilt of those who carry it on; but’”—she then enhances the comparison by lamenting—“‘as to the greater misery of the victims, I do not know where it lies’” (325). Tellingly, both Emma’s verbal participation and her typically hyper-critical evaluation of Mrs. Elton and Jane are missing; indeed, Emma’s overt presence is wholly absent from this scene, and indeed for most of the chapter.

This passage offers a useful moment to remind students that the rhetoric of women’s rights during the period was often linked to the cause of abolition. The conversation as Austen depicts it, however, underscores the problematic basis of comparison between abolition and women’s rights. Mrs. Elton both misreads and deflects Jane’s lament about the necessity of becoming a governess by stating that Mr. Suckling supports abolition; while the statement may be true, it in no way addresses Jane’s fundamental concern. Likewise, Jane’s comparison of the miseries involved in the state of slavery to those found in the condition of governesses seems, especially to modern readers, particularly hyperbolic and insensitive to the horrors of the slave trade. Emma’s fundamental disengagement from this scene—both verbal and critical—suggests the way in which she has little involvement in the issues that Jane and Mrs. Elton discuss. Asking students to discuss present-day acts of omission and silence in the face of social ills helps emphasize the tendency in Austen’s society and our own to ignore or suppress complex histories of social inequity.

Emma’s silence regarding issues of economics and race reverberates in telling ways soon after this incident, in chapter two of the third volume, when Harriet and a school friend encounter “half a dozen” begging gypsy children, “headed by a stout woman and a great boy” (361). Terrified and partially immobilized by a “cramp after dancing,” Harriet offers them a shilling, but they follow her, “demanding more” (361). Frank Churchill, happening upon the incident, breaks up the scene; Austen narrates, “The terror which the woman and boy had been creating in Harriet was then their own portion” (361). Of this moment, Michael Kramp observes, “Austen often depicts Highbury as a microcosm of England, highlighting the disruption of its present, the nostalgia for the past, and the anxiety over its impending industrial future” (148). With no explicit comment on what the gypsies’ presence or their begging indicates about the economic and social flux of Highbury, the novel resolves the incident by the end of the chapter, when the gypsies, who “did not wait for the operations of justice,” “took themselves off in a hurry,” leaving the “young ladies of Highbury” to walk “again in safety before their panic began” (364). Kramp astutely observes that “the juxtaposition of Harriet to the gypsies helps expose a strong social desire to incorporate the former and the extant cultural fear of the latter” (157).

Perhaps tellingly, Emma’s reaction to this incident almost perfectly mirrors her ruminations on the poor cottagers: ignoring the range of implications, she turns her attentions instead to a match between Harriet and Frank Churchill: “Could a linguist, could a grammarian, could even a mathematician have seen what she did, have witnessed their appearance together, and heard their history of it, without feeling that circumstances had been at work to make them peculiarly interesting to each other? . . . It seemed as if every thing united to promise the most interesting consequences” (362). Here, we again see Emma distancing herself from the broad, uncontrollable social issues that directly confront her by emphasizing the romantic schemes that she (incorrectly) believes that she can manage. Thus, while Emma encourages an element of change by imagining a connection between two people from disparate financial and social backgrounds, she nevertheless represses a sustained confrontation with the unstoppable social, economic, and cultural changes occurring in Highbury.10 Ruth Perry’s insight that these references “reveal the deep contradictions of the Enlightenment itself” enables students to access and critique these tensions in Austen’s own time as well as to think through how these oppositions mirror contemporary social injustices: “it was simultaneously an age of slavery and imperialist expansion; of wealth and poverty; of widening class division at home; of ancient lineages, great estates, and itinerant Gypsies; of expanding opportunities for educated men and continued dependence for educated women” (33).

The final scene that points to these contradictory social inequities underscores the ironic distance between the romantic resolution of the novel and the novel’s unresolved class-based tensions. Austen tells us that Mr. Woodhouse reacts to a series of poultry-house robberies in Highbury by believing his home is under threat of invasion: “Pilfering was housebreaking to Mr. Woodhouse’s fears.—He was very uneasy; and but for the sense of his son-in-law’s protection, would have been under wretched alarm every night of his life” (528). Emma’s father’s only source of solace is the protection of George and John Knightley; and since the latter must return to London and leave Hartfield, Mr. Woodhouse, “with a much more voluntary, cheerful consent than his daughter had ever presumed to hope for” (528), permits Emma and Knightley to marry. Like that of the impoverished cottagers and the begging gypsies, the presence of poachers indicates the continuing economic inequalities of Highbury society: with increasing enclosure of property, fewer resources were available to non-landowning people.11 No matter how diligently Mr. Knightley and Mr. Woodhouse send food to Mrs. and Miss Bates, no matter how (in)frequently Emma offers soup to the poor cottagers or arrowroot to Jane Fairfax, these forms of charity provide temporary relief that simply cannot address the fundamental causes of such structural and societal inequities. Nora, a student who was attuned to the short- versus long-term impact of community engagement activities, considered the novel and Emma’s behavior in this way: “Her act of providing soup, perhaps a bit of money, and a compassionate ear have all the effect of making her feel good about herself, but very little lasting impact on the long-term health and prosperity of the family itself.”

Despite the many failures of Emma’s encounters with people in and around the Highbury streets, there are ways in which students can also trace the initial steps that Emma takes to recover a better sense of place in Highbury society, from her increased attention to Miss and Mrs. Bates to her attempts to loan Jane Fairfax her carriage. To help students make connections among their service, readings, and their understanding of broader social inequalities, and to help them foster dialogue with one another, I created a two-part culminating project for the end of the semester. The first part, a “mock conference,” asked students to work in groups of three to present the connections and challenges they found in uniting their Austen research with their service-learning work. The second part asked students to write brief, individual reflection essays about their experience collaborating on their final presentation and about their work as a whole throughout the semester.

This final essay, composed after all coursework was completed, allowed students to build on their reflection activities throughout the semester to see how their understanding of Austen and the street had developed. In her final reflection, Vanessa, who tutored at 826LA, demonstrated how combining her service and research activities helped her understand Austen’s novels and broader issues of social inequality: “In Emma, Emma’s progression occurs based on her understanding of her social obligation to others. Hence the reader perceives her development from her initial, failed charitable attempt to perceiving Robert Martin as an educated man.” For Vanessa, Emma’s was partly a problem of lacking experiential knowledge of others. She continues, “In identifying [a lack of] education as a similar issue between the novels and contemporary society, it became evident that there is still progress to be made in ensuring educational access to all members of our community.”

Like Vanessa, Hayley, who worked with 18thConnect to correct OCR text of eighteenth-century documents to make them accessible for the visually impaired, also discovered a connection between academic work and the broader street beyond our classroom. She writes that by considering Emma’s character development through Musil’s service spectrum, she began to reevaluate her understanding of Austen and her role in the academic community: “I often only thought about what I could gain from the discipline, and how the discipline fit within my own narrative, much like Emma and the poor family. However, once I began . . . working with 18thConnect, I started to realize that I had a larger, personal responsibility to fully engage with the academic community I wanted to belong to.” Hayley adds, “I also hope to continue . . . to contribute to a group whose aims are so close to my own—making the humanities, and eighteenth-century literature, more accessible and useable for a larger population.” These responses demonstrated how valuable a range of service activities can be in unveiling and de-mystifying the various “streets” that seem alien to our students: from the regions surrounding our campuses to the chimerical-seeming academy itself.

Reimagining “the street” of Austenland

As teachers of Austen, we too can reconsider the connections that we make between our syllabi and the street. Looking forward, we might use the following methods to integrate civic engagement and intercultural inquiry activities into our work on Austen, whether or not we can include semester-long service-learning activities in our classes. To start, we can direct our students’ attention to passages that exemplify Austen’s depiction of the relationship between the individual and society: how Colonel Brandon, Darcy, and Knightley are defined as gentlemen partially by performing acts that sustain their communities; how Anne Elliot’s behavior towards the tenant-farmers of Kellynch Hall contrasts with her father’s obliviousness to his obligations; and how Mrs. Norris’s and Lady Denham’s acts of “charity” fail to work in Mansfield Park and Sanditon. We can also incorporate elements of community building by asking students to respond rigorously to one another’s work, from online discussion-board posts to in-class writing workshops that promote a shared sense of intellectual responsibility among classmates. Likewise, along with assigning traditional essays, teachers might facilitate a variety of forums that would allow students to share their research with one another and those beyond the classroom community. These assignments might include online blogging, as well as conference-style presentations where students read and discuss their work.

Along with the above activities, we might also find more ways of incorporating service-integrated activities in our courses. Regardless of the specific site location, forging meaningful partnerships with local agencies is key for a positive experience. Some teachers may find it useful to send students out into the street to tutor or to work in soup kitchens and homeless shelters; others may invite the street to the campus: perhaps staging screenings and discussion of film adaptations of Austen’s novels for senior citizens, or creating workshops that ask local community members to adapt sections of Austen’s novels to perform on campus. In so doing, we can help students understand how their particular geographic place has important implications for their own intellectual and everyday work. Underpinning all of these activities, we will ask our students to see how Austen’s plots are informed by power dynamics that cut across gender, race, and class lines. As teachers begin to take Austen to the street—and bring the street into discussions of Austen—more conversations will emerge about how Austen remains relevant to the imaginative and actual spaces and places within and beyond the classroom and campus. By implementing some of these strategies, we might begin to redefine the collective cultural image of Austenland.

Appendix

Please see the syllabus for the course discussed in this essay.

Notes

I thank the editors of this volume for their rigorous feedback on earlier drafts, Stephanie Harper and Hannah Jorgenson for their research assistance, and CSUN’s College of Humanities and Community Engagement Office for their generous support.

1. Oxford Dictionaries defines the term “First World problem” as referring to “a relatively trivial or minor problem or frustration (implying a contrast with serious problems such as those that may be experienced in the developing world.” The concept of First World problems has become popular as a series of Internet memes; one notable example shows two juxtaposed Venn diagrams, one of “First World problems” that include not being able to view a television show in HD; the “real problems” include hunger, rape, and cholera ( http://knowyourmeme.com/photos/142422-first-world-problems).

2. It is perhaps all the more telling that, as Linda Troost and Sayre Greenfield observe, Emma is the only major Austen novel set in only one community and location.

3. I thank Bridget Draxler for bringing this article to my attention at our 2012 NEH Seminar, “Jane Austen and Her Contemporaries.” On the emergence of service-learning initiatives at the University level, see Barber and Battistoni’s seminal article. More recent studies by Susan Ostrander and Kent E. Portney, along with Caryn McTighe Musil, attest to the continued growth of civic engagement on college campuses.

4. As of October 2013, there are no published studies considering Austen’s work in a service-learning context although the practice is certainly present.

5. A number of studies have cited the influence in particular of gender and race on civic engagement. Ostrander and Portney argue that “large numbers of low-income people and people of color, and sometimes women (Caiazza, 2005), have less access and opportunity for a variety of reasons to participate in public life” (4). On how race impacts civic engagement, see, for instance, Sarah Sobieraj and Deborah White’s “Could Civic Engagement Reproduce Political Inequality” in Ostrander and Portney’s Acting Civically (92-112). On the relationship between gender and civic engagement, see Amy Caizza’s “Don’t Bowl at Night” and Nancy Burns et al., The Private Roots of Public Action.

6. Mission statements are posted on the websites of these organizations. For 826LA, see http://826la.org/about/mission-statement/ for MEND (Meeting Each Need with Dignity), see http://mendpoverty.org/about-us/who-we-are/; for 18thConnect, see http://www.18thconnect.org/.

7. According to Peter J. Collier and Dilafruz R. Williams, there are four main components to successful reflective activities: they must be continuous (taking place before, during, and after service); they must be challenging (involving work that pushes students to connect concepts in new ways); they must be connected (acting as “a bridge between the service experience and our discipline-based academic knowledge”); and they must be contextualized (framing content and concepts appropriately) (83).

8. In this prompt, I asked students to consider one of the following: the cottager scene from Emma; the scene in Sense and Sensibility in which John Dashwood and Elinor discuss Colonel Brandon’s giving Edward Ferrars the living at Delaford (Volume III, Chapter 5); or the scene in Mansfield Park in which the Bertrams and Mrs. Norris discuss adopting Fanny (Volume I, Chapter 1); or the passage where Fanny seeks to improve Susan through education (Volume III, Chapter 9). Musil identifies “six expressions of citizenship: exclusionary, oblivious, naïve, charitable, reciprocal, and generative” (5). These categories begin with the most intellectually disconnected, exclusionary; on the other end of the spectrum, Musil defines reciprocal service as involving a rejection of the idea that the street is “deprived.” Instead, students see it as a resource “to empower and be empowered by”; generative service reflects the reciprocal mentality but also “has a more all-encompassing scope with an eye to the future public good” (Musil 7).

9. For the purposes of this essay, I have made anonymous all student responses. I have also silently corrected any obvious typos from the originals.

10. I am indebted to Bridget Draxler’s insightful observation for this particular reading.

11. For more information on Emma and the enclosure acts, see E. P. Thompson’s article and also Beth Fowkes Tobin (246, 253).

Works Cited

Austen, Jane. Emma. Ed. Richard Cronin and Dorothy McMillin. New York: Cambridge UP, 2005. Barber, Benjamin R., and Richard Battistoni. “A Season of Service: Introducing Service Learning into the Liberal Arts Curriculum.” PS: Political Science and Politics 26.2 (June 1993): 235-40. Bartel, Anna Sims. “Talking and Walking: Literary Work as Public Work.” Community-Based Learning and the Work of Literature. Ed. Susan Danielson and Ann Marie Fallon. Bolton, MA: Anker, 2007. 81-102. Burns, Nancy, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Sidney Verba. The Private Roots of Public Action: Gender, Equality, and Political Participation. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2001. Butler, Marilyn. Jane Austen and the War of Ideas. 1975. New York: Oxford UP, 1988. Caiazza, Amy. “Don’t Bowl at Night: Gender, Safety, and Civic Participation.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 30.2 (2005): 1607-31. Collier, Peter J., and Dilafruz R. Williams. “Reflection in Action: The Learning-Doing Relationship.” Learning through Serving: A Student Guidebook for Service-Learning across the Disciplines. Ed. Christine M. Cress et al. Sterling, VA: Stylus, 2005. 83-97. Cress, Christine M., et al. Learning through Serving: A Student Guidebook for Service-Learning across the Disciplines. Sterling, VA: Stylus, 2005. Cushman, Ellen. “The Public Intellectual, Service Learning, and Activist Research.” College English 61.3 (Jan. 1999): 328-36. “First World problem.” Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford UP, 2014. http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/First-World-problem Folsom, Marcia McClintock. “Introduction: The Challenges of Teaching Emma.” Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Emma. Ed. Marcia McClintock Folsom. New York: MLA, 2004. xvii-xliii. _____. “The Privilege of My Own Profession: The Living Legacy of Austen in the Classroom.” Persuasions On-Line 29.1 (Winter 2008). Greenfield, Susan C. “Of Jane Austen, the Bennet Sisters, . . . and VAWA?” Ms.blog. Ms. Magazine, 6 Mar. 2013. http://msmagazine.com/blog/2013/03/06/of-jane-austen-the-bennet-sisters-and-vawa/ _____. “Jane Austen Weekly: Child Poverty in Mansfield Park.” Huffington Post, 26 Oct. 2012. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/susan-celia-greenfield/jane-austen-mansfield-park_b_2024487.html Grobman, Laurie. “Is There a Place for Service-Learning in Literary Studies?” Profession (2005): 129-40. Hansen, Matthew C. “‘O Brave New World’: Service-Learning and Shakespeare.” Pedagogy 11.1 (2011): 177-97. Jay, Gregory. “Service Learning, Multiculturalism, and the Pedagogies of Difference.” Pedagogy 8.2 (Spr. 2008): 255-81. Karpel, Ari. “Would You Go to Austenland in Search of your Mr. Darcy?” Fast Company, 11 July 2013. http://www.fastcocreate.com/1683368/would-you-go-to-austenland-in-search-of-your-mr-darcy Kramp, Michael. “The Woman, the Gypsies, and England: Harriet Smith’s National Role.” College Literature 31.1 (Win. 2004): 146-68. Looser, Devoney. “‘A Very Kind Undertaking’: Emma and Eighteenth-Century Feminism.” Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Emma. Ed. Marcia McClintock Folsom. New York: MLA, 2004. 100-09. Mathieu, Paula. Tactics of Hope: The Public Turn in English Composition. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton, 2005. Musil, Caryn McTighe. “Educating for Citizenship.” Peer Review 5.3 (2003): 4-8. http://www.aacu.org/peerreview/documents/pr-sp03.pdf Ostrander, Susan A., and Kent E. Portney, eds. Acting Civically: From Urban Neighborhoods to Higher Education. Medford, MA: Tufts UP, 2007. Perry, Ruth. “Jane Austen, Slavery, and British Imperialism.” Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Emma. Ed. Marcia McClintock Folsom. New York: MLA, 2004. 26-33. Schwartz, Mary. “Public Stakes, Public Stories: Service Learning in Literary Studies.” PMLA 127.4 (2012): 987-93. Thompson, E. P. “Eighteenth-Century English Society: Class Struggle without Class?” Social History 3.2 (1978): 133-65. Tobin, Beth Fowkes. “The Moral and Political Economy of Property in Austen’s Emma.” Eighteenth-Century Fiction 2.3 (1990): 229-54. Troost, Linda, and Sayre Greenfield. “Filming Highbury: Reducing the Community in Emma to the Screen.” Persuasions On-Line Occasional Papers 3 (1999). White, Laura Mooneyham. “The Experience of Class, Emma, and the American College Student.” Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Emma. Ed. Marcia McClintock Folsom. New York: MLA, 2004. 34-46. Yu, Jean Y. “Race Matters in Civic Engagement Work.” Acting Civically: From Urban Neighborhoods to Higher Education. Ed. Susan A. Ostrander and Kent E. Portney. Medford, MA: Tufts UP, 2007. 158-82.

|