|

The archive is an anomaly in the digital age: its contents are tactile, unduplicable, irreplaceable, open only to those with the ability to travel, the academic identification to gain access, and the patience for slow and serendipitous searching. The speed, replicability, and accessibility of online information is not just an ideological alternative to the archive; it may even seem to make this research tool of yesteryear obsolete.1 Why travel halfway across the world to see Austen’s letters and manuscripts when we can view them, in all their searchable, sortable, saveable glory, with a few clicks of the mouse?

For scholars, the value of accessing an archive is clear: there are qualities of a text, including paper size and quality, seals, and watermarks, that cannot be fully seen or felt online. The illustrations, prefatory matter, or footnotes of a particular edition, or marginalia and markings of an individual copy, help us to contextualize a text within a particular cultural moment or even a particular household. The smell of the paper itself is thrilling for those of us who have committed our lives to the study of books. For researchers, the archive will continue to be essential in our field because the contents of an archive persist in their unduplicability.

For undergraduate students, however, digital archives and mass digitization projects open new ways to learn and, more specifically, new opportunities for undergraduate students to conduct humanities research in the archive.2 Translating Austen’s bits of ivory into bytes of data invites new research, and new researchers. Although the pedagogy of a digital Austen is still emerging, her life and work are particularly accessible to undergraduate humanities research, as many periodicals, letters, manuscripts, and early editions of her texts are available freely online.

The online archival resources for Austen are rich and varied: Google Books has numerous editions of Austen’s books and letters; British Fiction, 1800-1829 houses early reviews of, circulating library subscriptions to, and publishing information about her novels; the Hathi Trust Digital Library includes downloadable PDFs of her works and early Austen biographies; The Reading Experience Database lets users search readers’ responses to Austen as late as 1945; the British Newspaper Archive includes advertisements for first editions of Austen’s novels; and Jane Austen’s Fiction Manuscripts offers searchable digital versions of her juvenilia and unpublished manuscripts.

Although 18th Connect includes few references to Austen, its searchable collections include Austen’s early contemporaries. We may supplement archival research online with the Victorian Literary Studies Archive’s Hyper Concordance to the Works of Jane Austen, Austen’s entry in The Dictionary of National Biography, or the Morgan Library & Museum’s online exhibition “A Woman’s Wit: Jane Austen’s Life and Legacy.” Particularly worth visiting is What Jane Saw, an e-gallery of the 1813 art exhibit Austen visited at the British Institution in Pall Mall, London. The New York Times has described the gallery as a “meticulous reconstruction of the exhibition” that allows visitors to “put themselves, if not quite in Austen’s shoes, at least behind her eyes.”

Sites like NINES create online communities for scholars to exchange ideas, while Google Scholar has made scholarly research on Austen more easily searchable for scholars and more widely available to the public. In addition to university-sponsored sources, Janeites have created sites like Molland’s and The Republic of Pemberley, which offer free e-texts, Austen trivia, and message boards for community discussion. There are also sites that actively seek to bridge the divide between scholars and a wider online community, including The 18th-Century Common, which has created a “public space for sharing the research of scholars who study eighteenth-century cultures with nonacademic readers.” The site includes links and reviews for popular and scholarly sources online, along with announcements and CFPs. Persuasions On-Line provides open access to peer-reviewed articles for both academic and non academic readers united by an interest in Jane Austen. These online resources create a more democratic Austen: they build communities of scholars, students, and fans, who participate more actively and collaboratively in conversations about her life and works.

Digital archives and projects offer opportunities for students to fully immerse themselves in Austen’s literary context and write research papers based on direct access to archival materials. For instance, undergraduate students could compare Austen’s assessment of a novel with contemporary reviews, analyze visual cues in advertisements or book covers, contextualize Austen within a larger pool of contemporary female novelists whose works may be out of print, or study the cultural contexts that may have informed various Austen biographies.

In addition to these new possibilities for conducting undergraduate research, digital tools also provide new ways for students to collect and present this research. Because primary research can include a large number of small items—including book reviews, personal correspondence, maybe even tightly rolled laundry lists—students may struggle to organize the materials to produce an effective argument. How might students researching Austen’s letters, which may be scattered across various sites, go about finding a pattern and building an arc for their argument? They could benefit from creating a digital storehouse to collate such materials.

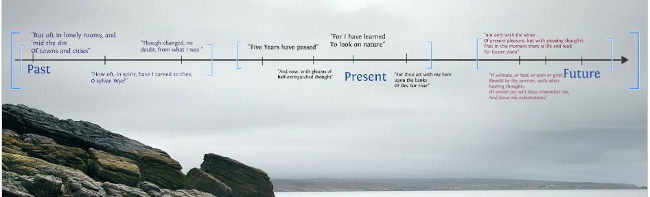

A timeline can help students visually organize their archival research both as they compile their research and attempt to form a hypothesis as well as when they present the finished argument. By creating a digital timeline, students can supplement a basic chronology of events with images, links, scans, and maps, drawing a virtual path through their research to tell a multimedia story of their findings. Beginning with my own archival research experiences using a digital timeline, I will also offer advice and resources for adapting these tools to the undergraduate college classroom and consider the impact of the digital humanities more widely on the future of Austen studies.

The digital literary timeline

I began experimenting with digital timelines as part of my own research process at the Chawton House Library,3 where I spent a summer tracking the friendship between Joanna Baillie and Maria Edgeworth. In order to organize decades of correspondence between two women with prolifically long literary careers, I created a timeline from May 1813, when the two writers met at a dinner party, through the late 1840s, by which time Edgeworth addressed Baillie as “My dear and constant friend in weal or love ever tenderly and cordial by sympathising!” (14 August 1848).4 I looked for evidence of how their friendship may have affected their writing, and a timeline helped me to keep track of an inordinately large number of letters and visits between them in addition to the publication dates of their many poems, novels, and plays. I organized the letters, secondary criticism, publication dates, literary excerpts, and biographical notes into a timeline using the visual presentation tool Prezi.5

The figures below provide examples of my first timeline. Figure 1 illustrates one year of the timeline, while the Figure 2 shows a close-up of the same timeline.

Figures 1 and 2: Excerpt from “Maria Edgeworth and Joanna Baillie” Digital Timeline

The timeline tells multiple, interwoven stories of unmarried, ambitious women writers experiencing aging, professional success, and personal tragedy; sharing stories of their mutual friend Walter Scott; and observing current events, including an emerging potato famine in Ireland (14 August 1848). Depending on which threads I followed, I found a different version of what their friendship meant to these women. By resizing items according to importance, highlighting key ideas with corresponding colors, and weaving a “path” along the central points, I told a story that traced Edgeworth’s eye troubles, which began in her childhood, through to Baillie’s 1823 poem “Sunset Meditation, Under the Apprehension of Approaching Blindness.” The timeline helped me to see patterns, intersections, and themes in a vast body of research, and it gave me a way to present this research to an audience like so many breadcrumbs along a trail.

The following summer, during the NEH seminar “Jane Austen and Her Contemporaries,” I developed a timeline that juxtaposed Austen’s composition of Northanger Abbey with her exposure to Gothic drama. According to a letter to Cassandra on 19 June 1799, Austen planned to see George Colman’s gothic spectacle Blue Beard, or Female Curiosity! in Bath on 22 June 1799, shortly after she began drafting Northanger Abbey. Colman’s hybrid tragic-comic tone, typical of Romantic melodrama, gave an ironic and playful nuance to the Gothic genre. The parodic tone of Austen’s novel might be more typical of the Gothic stage than the “seven horrid novels” mentioned directly in the text.6

The play may have inspired other elements of plot and character in Austen’s Northanger Abbey, as Blue Beard: or Female Curiosity! dramatizes paternal tyranny, misogynistic violence, and, as its title suggests, the suppression of female curiosity. Critics who have made connections between Austen’s novel and Colman’s play tend to use the play to note a parallel between General Tilney and Blue Beard, a Turk who beheads his wives for their curiosity.7 This reductive reading leads the reader-critic into the same imaginative mistakes as Catherine Morland, who falsely believes the General has murdered his wife. In the end, the more sinister (because seemingly benign) vices of Colman’s Ibrahim prove a truer parallel to Austen’s villain, whose greediness would also sacrifice the happiness of his children.8 And interestingly, the pivotal scene in Austen’s novel, in which General Tilney is misled about Catherine’s fortune and decides to invite her to Northanger Abbey, takes place at the Orchard Street Theater in Bath—the same theater where Austen saw Colman’s Blue Beard.

In my second Prezi digital timeline, I traced the confluence of Austen’s drafting of Northanger Abbey and her attending Gothic drama at the theatre in Bath, visually demonstrating the proximity of these events (Figure 3).

The Austen timeline was even more valuable to me than the Baillie-Edgeworth timeline because I had more puzzle pieces to organize, including playbills, letters, maps, quotations, images of playhouses, reviews, portraits, and links. The Austen timeline gave me a way to collect, organize, and present my research; however, this time, the top half of the timeline traced Austen’s writing process, and the bottom half of the timeline was a student tutorial that chronicled the process of creating a digital timeline (Figure 4). As part of the NEH seminar, I hoped to develop the digital timeline as an undergraduate research tool by creating tutorials to help them organize and share their own discoveries in the archive.

Digital archives in the undergraduate classroom

I introduced the digital timeline project to student researchers in August 2013 as part of SOfIA, or Summer Opportunities for Intellectual Activity, an undergraduate research program at Monmouth College. The “Jane Austen in Community” project invited four students—two incoming first-year students, one sophomore, and one senior—to spend three weeks researching Austen.

Our seminar had two major projects. First, the students created a series of community events related to Pride and Prejudice in celebration of its bicentennial, including a weekly reading group in partnership with the local public library and community arts center, and an evening of English country dancing and Regency-era food open to the public at a downtown theater.9 Second, students conducted original research projects on Austen that connected her to larger social, political, cultural, or literary contexts and then created digital timelines to present this research. In tandem, the two “Jane Austen in Community” projects contextualized Austen in her community and carried her to our community.

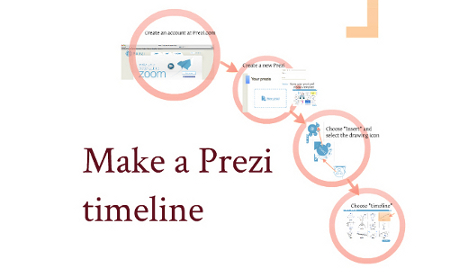

Our daily seminar sessions included discussions of the novel along with research and technology tutorials. In the first week of the SOfIA project, I introduced Prezi with basic lessons on how to sign up and create a Prezi timeline. We also talked about how to choose a topic and gather research using the campus library, online archives, and other digital resources. In the second week, we discussed the visual presentation of information and how to use color, size, images, graphics, or other strategies to visually prioritize and present the research. The last week included tutorials on how to draw a path to tell a story. A good argument, like a good story, builds logically and incrementally; it shows how students can use digital storytelling techniques to craft an effective argument. In addition, students used Screenr to create short videos of their presentation. This sample video, based on my “Northanger Abbey and the Gothic Afterpiece” research, provided students with an abbreviated example of a final video project.

“Northanger Abbey and the Gothic Afterpiece” Video, also available on Youtube.

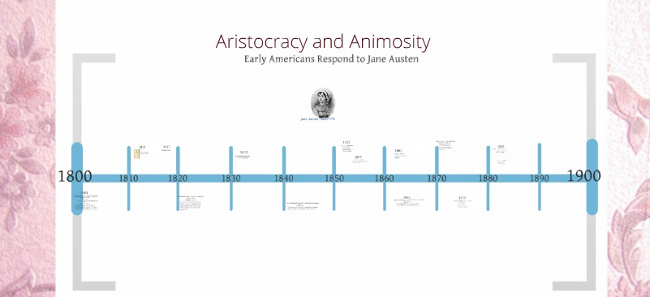

The students’ approaches to contextualizing Austen varied as widely as their approaches to visualizing their research. One student explored the paradox of early nineteenth-century American hostility to English social stratification and the simultaneous popularity of Austen’s novels after the first U. S. edition was published in 1832. This project presented these contrasting phenomena as parallels on either side of a timeline.

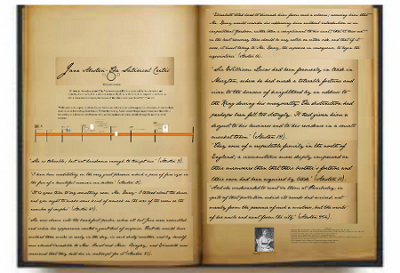

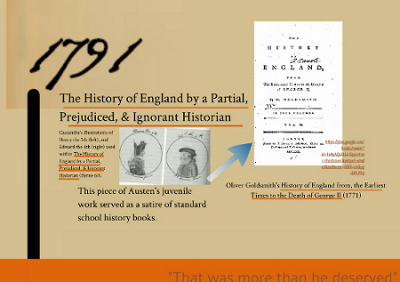

Another student researched Austen as a social satirist, and presented this research on the pages of a book with an embedded timeline followed by relevant primary and secondary quotations.

Figures 7 and 8: Close-up Screen Shot from “Jane Austen: The Satirical Critic”

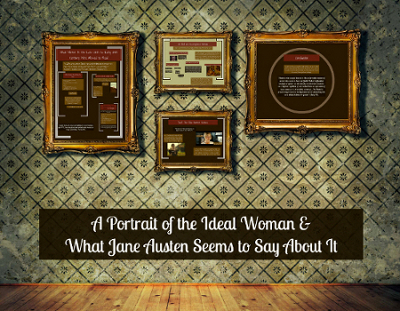

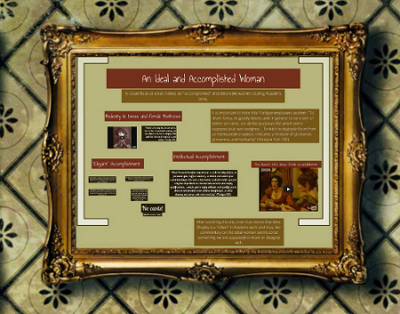

One student examined conduct books in order to explore late eighteenth-century “portraits” of the ideal woman. The student “framed” her argument as portraits on a digital wall.

Figures 9 and 10: Screen Shot from “A Portrait of the Ideal Woman and What Austen Seems to Say about It”

For each of these students, the ability to include multimedia components (including images, graphics, and videos) and an overarching spatial metaphor (such as a book, picture frames, or footsteps) guided and informed their research process. The task of populating a timeline that tells a story seemed less daunting to them than researching and writing a thesis-based paper, though the process and outcomes were similar: they gathered evidence, synthesized sources, identified themes, and formed arguments.

The biggest challenge students faced was completing the project in a three-week summer term. Several of the students had never read Austen before the seminar; only one had read scholarly criticism in literature; and none had worked in an archive. Even though students frequently submitted progress reports and met individually with me, we did not have enough time to do substantial drafting and peer reviewing. I anticipate that the project could be more successful in a regular-term, upper-level course.

In spite of these time constraints, however, students gained new perspectives on both Austen and their own research process. Students not only drew upon digital archives to create a timeline, but also authored their own digital archive. As digital curators, students experienced first-hand the difficulty and inherent subjectivity of choosing, evaluating, and interpreting content. They wrestled with questions of inclusion and organization. What is important? What is not? Which items are connected? What patterns do I see? How do these objects tell a story? By reflecting on their own digital curation, they saw both Jane Austen and digital technology from new points of view as these digital tools, archives, and projects created varied and overlapping contexts in which to read Austen’s life and work. When read together, their timelines knit a virtual patchwork of perspectives.

Although these projects provided students with valuable learning outcomes, integrating digital tools in the classroom can be tricky. Experimenting with technology requires patience, persistence, and a degree of trial and error. Embracing both successes and setbacks as “teachable moments” has made this approach to teaching worthwhile and rewarding to me.10

Digital research can and should be different from non-digital work; the bigger opportunity here is not necessarily to do traditional research better, but to change the paradigm for research itself. For instance, a student’s digital exhibit may have a unifying theme, but it may not have a thesis statement, because museums make arguments through decisions of inclusion and exclusion, by ordering and grouping items, and by noting patterns rather than by having thesis statements. By learning techniques of museum curation, students learn new strategies of argumentation—strategies that they can carry to other contexts. In a digital exhibit, students may also use multimedia objects like videos, images, and links alongside direct quotations from a novel as evidence to support their arguments.11 This variety of evidence affects the way students make arguments, and maybe even the arguments themselves.

In developing a research project for students with a digital component, teachers’ priorities may not change, but their methods might. Instructors need to figure out what they value most in student learning—such as close reading, critical thinking, or argumentation—and be open-minded about teaching these skills in ways that may look different from a traditional, hard-copy term paper. For instance, in this essay, I use external links in lieu of an MLA-style works cited page. This technique only works if I recognize that my goal for citation is not to demonstrate mastery of MLA style but to credit source material and quickly take readers to these sources. Likewise, my students’ final Prezi projects included transitions, but they did not look like typical transitions—they displayed connections between ideas visually. For instance, a ladder might signify incremental development in a list of items, while a scale may represent the weighing of contrasting possibilities. This strategy only works if we are creative in illustrating and interpreting visual correlatives for conjunctions.

These decisions raise important questions about technology, composition, and source attribution. Are hyperlinks a more efficient way for readers to access source texts? Do visual transitions show deeper understanding of the connections between ideas? Possibly—but only if we are open minded about how we define “citation” or “transition.” Teachers need to be creative, and we also need to be transparent with students about these goals and methods. These new tools give us an opportunity to discuss the purpose and value of citation, and explore or evaluate different strategies for citing sources. We should talk with students about our learning goals and why we believe a particular project is an effective way to reach those goals.

Whenever technology plays a role in a project, students tend to need extra guidance, encouragement, and time from the instructor. I tend to concentrate reading within the first two-thirds of my courses, so that students can devote their time at the end almost exclusively to research projects. I post self-paced technology tutorials on our course website, hosted on Wordpress, but I inevitably use a few class periods to walk students through the technology with screenshot-laden tutorials or rousing pep talks.

Whenever possible, I encourage students to help each other, sharing technology tips in class or even leading mini-tutorials. The senior English major in our SOfIA group, for instance, taught the incoming students how to find resources on our library’s website; another student who had used Prezi in the past helped her peers to get started. A student leader can become the “pointperson” in the class for a particular skill by mentoring peers who need extra help.

Digital projects would seem to work best in a seminar-style English major class with self-selected students. I have also, however, taught digital humanities projects in general education courses, where I have been pleasantly surprised at the value of having a tech-savvy engineer, a more visually-oriented artist, an emerging Janeite English major, and a student who has never finished a novel in her life work together on a project. There are more opportunities for peer-to-peer learning when students bring varied skill sets to the group.

By investing time in student-generated digital projects, such courses become focused less exclusively on literature, and more on the interrelationship between literature, archival research, and the digital humanities. Adding any new component to a course also means taking time away from other texts or topics, and I have struggled with hard choices of how to restructure my classes to include digital projects. For me, giving students this opportunity to conduct and publish original archival research and to take a meta-perspective on literary studies is worth the investment of time in and out of class.

Reallocating our time and rethinking our goals are important, but most crucially, teachers need to encourage students to be reflective and self-conscious about these tools, not only in terms of how they mediate the experience of reading or researching Austen, but also in terms of how they affect humanities research, the archive, and literary studies more broadly. We need to encourage students to weigh the value of digital and physical archives, the experience of reading Austen on the page versus the screen, and the learning outcomes of a traditional term paper or a digital humanities project. We need to ask students to think about what it means to be authoritative, and who has the ability to create, organize, and access knowledge in a digital age. We need to include students in these important, complex, and sometimes difficult conversations, as they are the future advocates of libraries, archives, and humanities programs.

If we use digital tools in the classroom thoughtfully and intentionally, including students in our reflective practice, then these resources have the potential to improve student learning in the following ways:

1. Digital literacy

Because students are digital natives, having grown up in a post-digital world, we might assume that they are also digitally literate. But students vary in their technological fluency, and few challenge the default uses of social media. Digital humanities projects like this one are an opportunity for students to learn to more effectively search for and evaluate digital resources and choose appropriate digital tools for different contexts.

The School of Information at the University of Michigan, for instance, is thinking critically about Digital Curation for Digital Natives, training a generation of digital natives to be digital archivists and preservation specialists. As their article explains, “Even though technology is intertwined in our students’ lives, many do not possess the information literacy skills or strategies for learning with technology or learning how to learn new technologies” (23). By integrating digital tools in our curriculum, we help students to demonstrate persistence, creativity, and integrity in their use of these tools. They will become more effective consumers of digital information, both inside and outside the classroom.

2. The writing process

As both a note-taking system and presentation system, the digital timeline begins as a catch-all and develops into a cogent argument. Students use visual cues like font, size, and color to create a hierarchy of information within their research, as a kind of virtual outline, thinking critically and reflectively about the choices they make in organizing their research. Because students can view each other’s works in progress online, it is also easier to run out-of-class peer review sessions, so that students can get peer feedback throughout their writing process.

3. Organization strategies

Students might use these timelines as a springboard for a term paper or senior research project; they might link them on a CV or graduate school application. My real hope is that they carry forward the skills they will learn in terms of searching, navigating, citing, sorting, organizing, prioritizing, and evaluating research. They might create a digital timeline to track the temporality in a time-hopping narrative like Slaughterhouse-Five or, as Cheryl Wilson has so beautifully done with “Tintern Abbey.”

A timeline is only one possible organizational strategy—students might apply the idea of a spatial metaphor to tag locations on a map for a geographically-driven argument, or they might find creative ways to visually display a cause-and-effect or pro-versus-con argument. These tools give our students new ways to categorize, tag, sort, and link information, and they let students tell narratives that are non-linear, but that are interconnected and spatially aware. In a world of information overload, the ability to organize knowledge may be an even more crucial skill for our students than the ability to find it.

4. Active learning

Digital humanities projects like the digital timeline are not just tools to help students organize: they are also tools to help students think. These resources allow students to study literature and history, as explained by Writing in a Digital Age, in a way that is engaged, participatory, and creative. By asking what it means to research Austen in a digital age, we begin to recognize that there are larger changes taking place—even fundamental changes to the kinds of questions that we ask as humanists.12 How, for instance, does technology mediate our experience or engagement with a text? How is the definition of text itself changing? How do digital tools change not just how we conduct research, but what and why we research in the first place, and with whom we share our findings? How does technology change our process of learning, our ways of thinking, or the way we see the world? What old assumptions about the humanities does technology challenge, and what new assumptions do we need to be aware of? How will collaboration and public scholarship shape the direction of humanities scholarship in the future?

These changes also affect who gets to ask the questions. For example, digital projects can help students become knowledge-creators rather than knowledge-consumers. In the 2013 article “Learning, Teaching, and Scholarship in a Digital Age: Web 2.0 and Classroom Research: What Path Should We Take Now?” Christine Greenhow, Beth Robelia, and Joan E. Hughes argue that “Web 2.0’s affordances of interconnections, content creation and remixing, and interactivity might facilitate an increased research interest in learners’ creative practices, participation, and production” (249). According to the authors, Web 2.0 technology affords an interactive learning process in which “knowledge is decentralized, accessible, and co-constructed by and among a broad base of users” (247). The ability to create, share, exchange, remix, and comment makes learning online fundamentally collaborative, and students play a more active role in their own learning.

In Teaching History in the Digital Age, T. Mills Kelly suggests that “by giving students the freedom to experiment, to play with the past in new and creative ways, whether using digital media or not, we not only open ourselves up to the possibility that they can do very worthy and interesting historical work, but also that there are significant learning gains that result from giving students that freedom” (5). If we want our students to be critical thinkers and active learners, we need to give them freedom and trust to work in ways that demonstrate what Cathy Davidson calls twenty-first century literacies such as creativity, collaboration, and recontextualization.

The future of Austen studies in a digital age

These new ways of learning will also inform the future direction of Austen studies, which will be driven increasingly by the values of creativity, collaboration, and recontextualization. In addition to collaborating with online communities to gather information, feedback, and guidance on digital humanities projects, we should also collaborate with librarians, curators, and archivists, who can offer insights on the complexities of digital curation, metadata, authorship, publication, and preservation within digital humanities research. I hope to see more research from humanists that credits staff and students as collaborators or co-authors.

Technology coupled with a collaborative research methodology has also enabled new interdisciplinary subfields like “literary neuroscience,” which has used MRI brain scans to confirm what we, as admirers of Austen, already know: reading Jane Austen makes us smarter. Researchers at UN-Lincoln are attempting to tag and code Austen’s free indirect discourse in order to see if it is stylistically discernible to a computer program. Non-native English speaking students are reading Austen at the intersection of literature and linguistics, using collocation analysis as a form of literary analysis, while international adaptations have paved the way for alliances between Austen studies and film studies scholars to explore Austen’s multicultural relevance today.13 Future Austen research will continue to reach creatively across disciplinary boundaries as technology gives us—and our students—new ways of reading, interpreting, and analyzing texts.

Digital archives also open new possibilities for contextualizing Austen within the study of her contemporaries. The 2010 British Women Writers Conference included a session titled “Teaching and Researching British Women Writers in the Digital Age” that grappled with the complexities of inclusion within digital archives, particularly concerning women writers. Maura Ives, a panelist from Texas A&M University, argued that the construction of knowledge in digital spaces is never innocent.14 We need to examine what is and is not included, who makes these decisions, and how these decisions are made—and I would add, we need to include students in these conversations.

Ives pointed out that because specialized databases are often prohibitively selective in their holdings, much of the most interesting work in digital archives takes place in open-access, uncurated spaces.15 With Google Books, for instance, no one is bothering to “weed out” the women and obscure figures, so readers, scholars, and students are not limited to a list of texts or authors that someone else has predetermined as worthy of scholarly interest. While feminist scholars have worked for years to recover long-forgotten women writers, the Web is quickly becoming the great canon-blasting democratizer of literature.

Of course, the mantra of “if you build it, they will come” is no guarantee online, and posting novels by obscure writers—or student or scholarly projects, for that matter—does not automatically draw a wide and eager audience. Freshman composition essays, class blog posts, and boutique archives may reach few readers, if any. But Jane Austen? That’s a different story. Austen is poised to succeed in the digital age, as her crossover classics have already bridged professional and pleasure readers. While all of literary studies is in a moment of transition, Austen studies, with a robust and diverse global community of readers and researchers, is uniquely situated to take advantage of digital tools that are redefining the potential authors and audiences of twenty-first-century scholarship.

Digital archives and online presentation tools make Jane Austen more accessible, but more importantly, these tools empower unlikely or unexpected researchers, including students, to make active contributions to scholarship on Austen. In her video Collaboration by Difference, published by the Harvard Business Review, digital humanist and HASTAC co-founder Cathy Davidson says, “It’s often the non-expert, the outlier, the odd-ball, or the person who isn’t in charge who has the most innovative or important thing to say. You have to structure ways to hear that person or you will always drown him or her out. We call this collaboration by difference.”

Jane Austen studies may be the ideal place for this kind of collaborative approach to knowledge creation, as “non-expert” specialists abound—students, fans, and Janeites are creating some of the most creative digital tools and projects on Austen, including The Lizzie Bennet Diaries, a modernized adaptation of Austen’s Pride and Prejudice via video blog; Jane Austen Unbound and Ever, Jane, role-play video games set in Regency England; and Write Like Jane Austen, an Austen-inspired thesaurus.

The bicentennial anniversaries of Austen’s novels reflect this increasingly democratic approach to Austen studies, which models creative and collaborative efforts to celebrate Austen. The Chawton House Library, which itself functions as both scholarly archive and Austen pilgrimage destination, has collated a comprehensive worldwide calendar of events for the bicentennial that includes everything from academic conferences to community film screenings, faculty lectures to Regency dance workshops. Claudia L. Johnson’s Jane Austen’s Cults and Cultures explores the history of Austen fandom, while Susannah Fullerton accessibly analyzes translations, adaptations, and illustrations in her Celebrating Pride and Prejudice: 200 Years of Jane Austen’s Masterpiece. Readers who buy one text on Amazon will be told that “customers who bought this item also bought” the other. Are fans buying “scholarly” books, or are scholars buying “fan” books? It is probably a bit of both, if we dare draw a line between them at all. And, for our students, seeing both Austens—or many Austens—gives them a richer and more nuanced understanding of both the complexities of resource reliability, and the ways we define the “authentic” Austen.

There is no single authoritative online resource for Jane Austen, and that is a good thing. Digital tools help our students to hold multiple truths about Austen at once: Austen is included in both eighteenth-century and nineteenth-century archives.16 She can fit in both a timeline of feminist writers and a timeline of conservative writers. Austen is both a private writer, who relied on the creaky hinge of a door to warn her of approaching company as she wrote, and a delighted playgoer, museum visitor, and observer of society, who delighted in a trip to the city. She is both a writer of her time, influenced by the politics, literature, and culture of her day, and a writer of our time, continually reframed and refreshed in new adaptations and interpretations. Through the medium of the aptly-named web, students can move from site to site, appreciating both the insight that each resource offers individually and the vision of Austen that these resources offer as an interconnected whole, giving them new ways of appreciating the both/and of Austen.

We are only beginning to see the possibilities for how technology and the digital humanities will change how students experience Austen. What if digital archives of Austen included texts she read in addition to texts she wrote? What if digital copies of Austen’s texts would link directly to textual allusions as we read? What if the 15,000 entries in Deirdre Le Faye’s seminal Chronology of Jane Austen and Her Family were tag-able, searchable, and linked to chronologies of contemporary women writers? What if students read Austen the way they read online, navigating through connections and links non-linearly, based on curiosity more than chronology? In a digital age, when students, scholars, and fans can access, remix, or even create digital archives, reading Austen “in context” is increasingly becoming not just possible, but unavoidable.

Appendix

Please see the syllabus for the course discussed in this essay.

Notes

1. Technology is often surrounded by either utopian or dystopian rhetoric. Robert Darnton has addressed the fears that digitization will make libraries obsolete, including at his 2011 keynote address “The Research Library Today: Three Jeremiads in Search of a Happy Ending” at the University of Missouri symposium “The Future of the Archives in a Digital Age.” He argued that digitization is not the death of libraries, but instead a metamorphosing rebirth. At the “Platforms for Public Scholars” Humanities Symposium (sponsored by The University of Iowa Obermann Center for Advanced Studies, 15-17 October 2009), Scott McLemee described the utopian beliefs surrounding the rise of the virtual sphere as parallel to the eighteenth-century rise of the public sphere, founded on principles of open access and democratic discussion. In reality, technology can change our teaching for better or worse. For ongoing discussion on best practices for integrating technology into the classroom, visit HASTAC; in particular, I recommend Cathy Davidson’s post “If We (Profs, Teachers) Can Be Replaced by a Computer Screen, We Should Be!”

2. See Lara Karpenko and Lauri Dietz’s “The21st Century Digital Student: Google Books as a Tool in Promoting Undergraduate Research in the Humanities.”

3. The Chawton House Library is a great example of an archive that sees community-building as the greatest asset of a physical archive in a digital age.

4. This letter comes from the Hunter-Baillie Papers Vol. 9 at the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

5. Prezi, a variation of PowerPoint, is an online information visualization tool that uses one large canvas rather than individual slides to organize and present text, images, and video. Users navigate through the canvas by zooming in and out, creating a more interconnected narrative.

6. Isabella Thorpe’s reading list includes The Castle of Wolfenbach, Clermont, The Mysterious Warning, The Necromancer of the Black Forest, The Midnight Bell, The Orphan of the Rhine, and Horrid Mysteries. Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho is a favorite of Catherine Morland, Isabella Thorpe, and Henry Tilney; other plot details mirror Radcliffe’s A Sicilian Romance and The Romance of the Forest. For further reading on Gothic literature and Northanger Abbey, see Bette B. Roberts’s “The Horrid Novels: The Mysteries of Udolpho and Northanger Abbey” in Kenneth Wayne Graham’s edited collection Gothic Fictions: Prohibition/Transgression (89-111) and Andrea Rehn’s excellent article in this issue, “‘Hastening Together to Perfect Felicity’: Teaching the British Gothic Tradition through Parody and Role-Playing.”

7. Casie Hermansson, for instance, reads General Tilney as a Bluebeard figure in her 2001 Reading Feminist Intertextuality Through Bluebeard Stories (134).

8. In Coleman’s play, Ibrahim encourages a romantic attachment between Selim, a soldier, and his daughter Fatima, until a wealthier suitor arrives and he abruptly rescinds his earlier matchmaking efforts. In the opening scene, Selim confronts Ibrahim about breaking his engagement, and Ibrahim explains that when you “throw Riches and Power into the scale . . . simple merit soon kicks the beam” ( Colman 3). Like Ibrahim, Austen’s General Tilney encourages a match between his son and Catherine, only to retract it for similarly mercenary motives, as “she was guilty only of being less rich than he had supposed her to be” ( Austen 170). Both Gothic parodies indulge in violent fantasies that mask a more subtle patriarchal tyranny.

9. The community events, while not the primary focus of this essay, added an element of civic engagement to our project. We had seventeen participants in our reading group, ourselves included, which met at the Buchanan Center for the Arts each week to discuss one volume of Pride and Prejudice. Over eighty people in the community attended the “Having a Ball with Jane Austen” event, which included food and dancing at the Rivoli Theater in downtown Monmouth, IL.

10. In Digital Humanities (2012), Burdick et al. describe the “Generative Humanities” as “a willingness to embrace productive failure, and the realization that any ‘solutions’ generated within the Digital Humanities will spawn new ‘problems’—and that this is all to the good” (5).

11. The value of asking students to “curate” Austen has already been explored by Phyllis Roth and Annette LeClair in “Exhibiting the Learning: Austen’s Legacy on Display,” which was published here in Persuasions On-Line in 2008. The article draws a similar analogy between exhibit curation and paper writing: “the students quickly understood that what they were doing was creating a visual version of a piece of writing with a thesis and supporting paragraphs, and that the visual required some help from the written. . . .[T]he exhibit cases would comprise a chronological experience for the viewers. Thus, as in a clear, coherent piece of writing, the audience would be led from one deliberate view of the subject to others.” The authors describe the students’ shift from the mere accumulation of information to the careful sorting, organizing, and editing involved in curation as reflecting the interpretive work of literary criticism.

12. We often think of the digital humanities as using digital tools to do humanities research, but it can also mean applying humanist questions to a digital age. The NEH Office of Digital Humanities supports this dual nature by funding projects “that explore how to harness new technology for humanities research as well as those that study digital culture from a humanistic perspective.”

13. See Kathryn Sutherland’s “Jane Austen on Screen” or Jodi Wyett’s excellent essay in this collection, “Jane Austen Then and the Now: Teaching Georgian Jane in the Jane-Mania Media Age.”

14. A recent NPR article, “What’s In A Category? ‘Women Novelists’ Sparks Wiki-Controversy” offers an example of how Wikipedia controversially excluded women writers from the “American Novelists” page in favor of a separate category of women writers.

15. Single-author databases, for instance, have become more common in recent years; even the digital archives discussed here often include a sampling of writers from a particular period or a niche collection from a particular archive. While we have become accustomed to the comprehensiveness of the Google Search, archival research still tends to require digital “trips” to multiple places, and digital archives are still limited by curators’ decisions of what to include and what to leave out.

16. See Misty Krueger’s article in this collection: “Teaching Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey as a ‘Crossover’ Text.”

|