Austen Chat: Episode 10

April 4, 2024

Jane Austen & the Decorative Arts: A Visit with Kristen Miller Zohn

During the Georgian era, gender differences in domestic goods became increasingly common. For example, a gentleman's writing desk was a sturdy, substantial piece of furniture, while a lady’s desk was a small, delicate writing table. In this episode we sit down with art historian and museum curator Kristen Miller Zohn to discuss gender and the decorative arts in general, and how Austen’s references to consumer goods in her novels—from furniture and wallpaper to breakfast sets, muslin gowns, and toothpick cases—reveal important information about her characters.

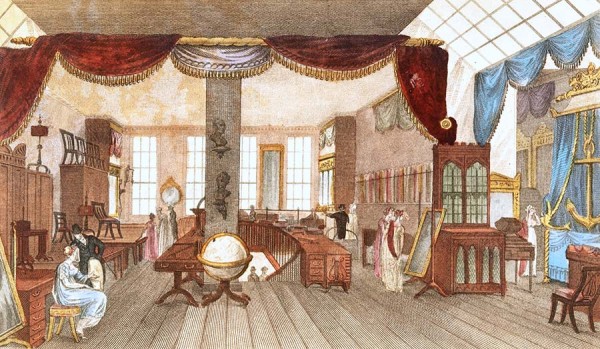

“Messrs. Morgan and Sander’s Ware-room, Catherine-Street, Strand"

Art historian Kristen Miller Zohn is the Executive Director of Costume Society of America and curator for the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art in Mississippi. Her articles on Austen and the fine and decorative arts have been published in Persuasions and Persuasions On-Line, and she has presented at eight JASNA AGMs. A Life Member of JASNA, she was a co-coordinator for the 2021 AGM in Chicago.

Show Notes and Links

Many thanks to Kristen for appearing as a guest on Austen Chat!

Related Reading:

"Gender and the Decorative Arts in Austen's Novels," Kristen Miller Zohn, Persuasions On-Line, Vol. 43, No. 1 (Winter 2022)

Links Mentioned in this Episode:

![]()

Listen to Austen Chat here, on your favorite podcast app (Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and other streaming platforms), or on our YouTube Channel.

Credits: From JASNA's Austen Chat podcast. Published April 4, 2024. © Jane Austen Society of North America. All rights reserved. Image: “Messrs. Morgan and Sander’s Ware-room, Catherine-Street, Strand.” Rudolph Ackermann, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions, and Politics (1st series, vol. 2, July–December 1809). Metropolitan Museum of Art. Music: Country Dance by Humans Win.

Transcript

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and readability.

[Theme music]

Breckyn Wood: Hello, Janeites, and welcome to Austen Chat, a podcast coming to you from the Jane Austen Society of North America. I'm your host, Breckyn Wood from the Georgia Region of JASNA. Today with me, I have JASNA veteran and Georgian-era expert Kristen Miller Zohn. Kristen is an art historian who works as Executive Creative Director of the Costume Society of America and as Curator for the Lauren Rogers Museum of Art in Mississippi. She has presented at eight JASNA Annual General Meetings—most recently at the 2022 AGM in Victoria, British Columbia, where she spoke on "Gender and the Decorative Arts in Austen's Novels." Okay. Hi, Kristen. Welcome to the show!

Kristen Miller Zohn: Hello. Thank you.

Breckyn: Before we get into your AGM presentation, I like to start with a segment called "Desert Island." You're stranded on a desert island and can only bring one Austen work with you. Which do you choose and why?

Kristen: Well, I was going to cheat, because when I started rereading Austen again after grad school, I decided now that I had time, I could read all of them. And so, I went and got the collected works.

Breckyn: Oh, yeah, that's cheating. Not allowed.

Kristen: It's also really bad because that book is very thick and my thumbs really hurt. I was happy to get the Kindle complete novels version when it came out. But if I had to choose one, my favorite novel is Persuasion. But if I'm on a desert island, I'm going to need more things to occupy my time. And I feel like Emma would be fun to have because I could go back and look at all the mystery clues for the Jane Fairfax-Frank Churchill relationship with that in mind and help see how soon the mystery gets solved.

Breckyn: That's a great choice. That's an interesting move—to not pick your favorite—because I think most people's instinct would be to just pick your favorite, but . . . I like that. That's great. Okay, so let's talk about your AGM presentation. You mentioned in there that the gender differences in domestic goods became a lot more pronounced during the Georgian era. Can you give us some examples of that? What was going on at this time?

Kristen: The Georgian era really is the beginning of the modern era in terms of consumer goods. The industrial revolution had made things a lot cheaper to make, so you could do things half handmade and half machine-made. And so a lot of things like silver and furniture were getting done, not in full-factory style, but in much more automated style than they had before. So, they were a lot less bespoke and more made for market. And so, people like Chippendale in the 18th century were putting out design books for his cabinetmaker shop and marketing things that way. So, instead of it being just the upper echelon having this furniture—this very elegant furniture—more of the middle and upper middle classes were now able to afford it because it wasn't as expensive as it had been before.

And it's also the golden age of when advertising starts, too. So, all of those things coming together led manufacturers and makers to want to market their goods. And so, you're always looking for a marketing angle. And so, they could market things for different rooms of your house, because at this point, before the Georgian period, rooms were not so succinctly—they didn't have such succinct functions, so you could use a room for multiple functions. But this is the era where we get things like dining rooms and breakfast parlors and things like that. So, you could have specific furniture made for specific rooms. You could have things made for specific tasks. You could have writing desks and dressing mirrors, things like that. And so, another way you could distinguish things marketing-wise was gender-wise. Gendered furniture had always existed because, for instance, men don't really use birthing stools, but they weren't really called "gentlemen's" and "ladies'." At this point, it's—another way to market these goods is to say, ladies' or gentlemen's tables.

Breckyn: Would all of this marketing have just been done in newspapers, or—where were people seeing these advertisements?

Kristen: They were seeing them in trade cards and newspapers, and then also in these design books—these design catalogs that you could buy. There weren't billboards, obviously, but there were other ways to advertise. There are some beautiful trade cards from the period. A lot of museums have great examples of these engraved cards—fantastic images of wallpaper stores and things like that. You can go down that route . . .

Breckyn: Yeah, I love the visuals in your written-up presentation on JASNA's website, and I'm going to direct listeners to that at the end. If you want to see all of these things that Kristen is talking about, there are some really cool pictures and also some really funny illustrations of more cartoony things from the time period.

Okay, so I like how you point out in your presentation that even though there's a gender divide in the acquisition of these household goods, couples often work together to pick them out, right? You give the example of Elinor and Edward Ferrars from Sense and Sensibility, and I have the quote here: "The first month after their marriage was spent with their friend at the mansion house from whence they could superintend the progress of the parsonage and direct everything as they liked on the spot, could choose papers, project shrubberies, and invent a sweep." I love that. Can you tell us a little bit about what that means? What are those three things in modern parlance?

Kristen: So, they chose wallpapers, and they decided on ornamental plantings outside, and then they put in a curved carriage drive. Those are those three things. And so in general, men, because they were the head of the household, would be in charge of the major redecoration efforts. So, if a whole room or a whole suite of rooms or a whole house was going to be done up, the husband was the one—his name was on the bills at the merchants. In name, he would have been in charge. And then women were responsible for smaller items like breakfast sets and things like that, or individual items, or to replace items that were broken. But of course—so that was the norm. But of course, it depended on what your relationship was like, full stop. How much power a man would have given a woman to help in making any of those choices. So, this is one way that we know that Elinor and Edward are suited for each other, because they're doing this together.

Breckyn: So, you also mentioned that, historically, men have indulged in shopping just as much as women, right? Why do we have this negative association with women being just materialistic spendthrifts?

Kristen: Because most of the purchasing of the more mundane items, the everyday items, were handled by women, and so they were just more visible in the marketplace. And so they were more associated with shopping. But yes, of course, men loved shopping just as much as women. And there's prints of the time that show showrooms full of men and women: Wedgwood's and the Morgan and Sanders’s warehouse room, which was for furniture. There are some great prints that show men and women both partaking in shopping activities. But you know, if—shopping has to do with acquisition, which can be associated with something like greed and vanity. And so, if there's a negative aspect to something like that, then it's going to be given to women—with clothing too—fashionable people are seen as being frivolous, and women are being seen as having more interest in fashion. And it's been pointed out that that might be because women had to be more fashionable because their appearance mattered more in the marriage market than men's did and do, really, truthfully. This is still a stereotype that we have, and it was definitely prevalent during that time. Anything with acquiring things and appearances—if it was done in moderation, then it could be by both sexes. But if it was in any way seen as frivolous, then that distinction was given to women.

Breckyn: I like how Austen counters this. We get the foppish Robert Ferrars and his fussy toothpick case, which is just one of the greatest scenes in all of Austen. Also, Sir Walter Elliot comes to mind, right? An exceptionally vain man who cares a lot about his clothes and his appearance.

Kristen: Way too many mirrors in his dressing room that—

Breckyn: Exactly.

Kristen: Then there's a duplicitous shopper in Frank Churchill, who goes and buys Jane Fairfax's pianoforte without letting anyone know who has done it.

Breckyn: What do you think that reveals about his character? Is that just that he's sneaky or that he just likes to play jokes on people?

Kristen: It does show that he truly does love her and wants her to have the best things, but it shows that he's also thoughtless, because he doesn't have to deal with consequences for anything. And so, he has not had to think about what receiving this pianoforte will mean for her—first of all, in terms of the gossip that it will engender, but, secondly, where the heck it's going to go? Because she lives in a tiny little place. It's going to take up—so, he's not a practical thinker is what it shows. It does show that he has her interest at heart, but without much thought.

Breckyn: The pianoforte is a good segue. You mentioned this a little bit more, but I want to hear more of your thoughts on how furniture starts to reflect this gender divide during the time period. What are some distinct pieces of girly, feminine furniture and then stout, manly furniture that we get?

Kristen: There's a great illustration in Thomas Sheraton's catalogs. In my article, I show one from 1803 that has a lady's writing table and a gentleman's secretary. They're both places for people to write letters. The female's is just tiny and very delicate, and the man's is very substantial and has room for all of his documents. It just looks like he's going to do business at his, but the women—they're just going to write some funny little letters, and there's nothing important going on at the lady's writing table.

Breckyn: Yes. No, that's true. That brings me to something I wanted to talk about. From everything that I've read about Austen's life, it seems that her family actually took her writing very seriously, and they didn't just brush it off as this silly feminine pastime. Her father, when she was young, always kept her well-supplied with books and writing materials, and her brother Henry helped to get her books published. Do you think that Austen was a lucky exception to the general rule of the time, or do you think that something else was going on?

Kristen: Well, as an art historian, I know a lot more about female artists, too, and how they were able to do work in a time where women could not be professional artists, much like—there were few and far between women visual artists in addition to female authors. And most of the time, you have to have a family that is amenable to this happening. A lot of the great women artists had fathers or brothers who were artists who let them study from the nude when that was not really allowed by women. So, it helps to have, if you're going to be successful, to have somebody who is on your side in your family. I find it interesting, though, that Austen—she talks about Mr. Bennet in Pride and Prejudice having his library. And we've just been on a discussion with some JASNA Georgia folks who pointed out that that's his man cave. And so, he's got a place to go and be quiet and do his business. But Austen is writing at a small table in a public room in her house, and she doesn't have her own library to go to to retire. So, she's not really being treated as a professional writer. She doesn't have a special place designated for her to do this writing.

Breckyn: She doesn't have "a room of one's own," as Virginia Wolf says, right?

Kristen: Exactly. So, their support only went so far, and that's totally in line with what the gender roles—what would have been expected from gender roles at that point.

Breckyn: Right. Let's talk about Northanger Abbey, because you focus on that a lot in your presentation. I've always been creeped out by General Tilney. I think we're supposed to be. He's just so controlling and domineering. But I didn't really realize until I read your presentation how petty he is in his tyranny. There's a line from your presentation where you say—you mentioned that “he involves himself in household matters great and small, important and frivolous, substantial and delicate, turning everything into a masculine concern." Like nothing escapes his terrifying gaze.

Kristen: So, he's really associated with architecture and domestic objects in Northanger Abbey. There are several passages where he's giving Catherine a tour of the abbey, and he's pointing things out. He knows every single thing that's in his dining—in his drawing room. He's got two drawing rooms: one that's used with people of importance. He's not only taking over the male role of doing the major refurbishment of the house, but he's also getting little things that would have been a woman's purview, like he's very proud of the breakfast set that he chooses and has this false modesty that, 'Oh, it's two years old. It's very old. I mean, I should have a current one.' So, he's humble bragging about how up to date he is with his decorative arts. He has a garniture on the top of a fireplace. He's dealing with all these small types of objects, decorative art projects that probably his wife would have wanted to pick out or Eleanor after she takes over as head of the household. But you get the impression that he's chosen every single thing in that house and that none of the women in his life have had anything to do with anything.

Breckyn: He refuses to relinquish control.

Kristen: Exactly, on anything. He does do scientific improvements in the kitchens. They have all the latest kinds of stoves in the kitchens there, which is a masculine thing. But according to designers of the time, there shouldn't be anything scientific in a female room, and he's put a Rumford stove—a Rumford fireplace—into one of the drawing rooms. And so, this was a pretty new type of fireplace that had just been published a couple of years before the first version of Northanger Abbey was written. And it's a fireplace that is contracted, so the walls are brought in at an angle, and so it pushes more heat out into the room. And, so, he's got one of those. So, it's in a female space that he has put this masculine, scientific—

Breckyn: It's almost like he's manspreading, to use a modern term.

Kristen: Yes. Not only that, but he manspreads his greatcoat in the curricle when he is going to be in the curricle with Henry. He takes up—he has his greatcoat spread out instead of wearing it, and so it takes up more than his fair share of the room in the curricle.

Breckyn: Exactly. Let's talk about greatcoats. They're manly, they're dashing, they're dramatic. What's not to love? You mentioned a couple of examples where greatcoats come up in Northanger Abbey—the one you just told us about General Tilney manspreading in the curricle. Where are some other times where it gets mentioned?

Kristen: We know that Mr. Allen does not like to wear a greatcoat. His wife says he never goes out in one, and she doesn't understand why. But then Henry is mentioned three times with the greatcoat, and that's more than any other character in Austen. And so, it just stood out to me, and it also stood out to me particularly because not only is Henry associated with these greatcoats, but he's really associated with muslin, which is a very female fabric. So, it was so associated with females that it was used as slang for female, like "a little bit of muslin on the side." So, he's associated with both masculine and feminine objects of clothing. And it struck me really as being significant, because this is the time in fashion history when men are switching to practical clothing. Whereas before this practical clothing was worn by the lower classes, now, men in this in neoclassical dress are switching to practical clothes. They're not wearing the silks and brocades of earlier times. Their hair isn't powdered. They don't have lace cuffs. Now, they're wearing things that look like they are overseeing their country estates and that also have much more slim silhouettes, like Greek and Roman statues—classical statues that they're looking at.

So, they're practical in that they're closer fitting, so they don't get in the way when you're doing practical things. But they're also made out of things like plain wool and buckskin as opposed to silk. And the greatcoat is a great example of this because there's no other embellishment except for that it has a couple different layers of capes on the shoulders. It's to keep the rain off; it's a very practical garment. It's really associated with coach drivers. But at this point, it starts to be worn by fashionable young men as well as they're driving their own carriages. And so, it's a dramatic object. It's a dramatic garment, but not because it's embellished. It's because of its cut and its silhouette. And so, the fact that Henry is associated with both of these things, just like his father is associated with both masculine and feminine decorative arts and rooms, the fact that Henry is associated with both masculine and feminine things gives them a parallel. But whereas General Tilney is doing it just so that he can have complete control over everything, Henry does it in service of his sister. So, he knows about muslin, and his sister has allowed him to choose her fabric for her gowns for her, and he really can get into the mindset of a woman.

Kristen: And he knows that—so muslin is not a practical fabric. And so here, again, we have this contrast between the frivolous impractical female object and the substantial impractical male object, just as we saw in the furniture. These two garments that are associated with Henry really point out that binary. He, though, is appreciative of both. And even though he realizes that muslin can be fragile, that something always can be made practical out of it. So, you can make a handkerchief or something out of it when the muslin frays. There is worth in the feminine fabric and also the women that are associated with it.

Breckyn: Right. And he's just so likable. I think Henry Tilney is one of Austen's most endearing heroes. And so, whereas these characteristics of understanding the feminine and being involved in the female aspect of these domestic goods is really endearing with Henry and it makes him relatable, it's just creepy and off-putting in General Tilney. I think, like you pointed out, that's a really interesting parallel between those two characters.

Kristen: He says it specifically, too, in his very first conversation with Catherine. He says, "In every power, of which taste is the foundation, excellence is pretty fairly divided between the sexes."

Breckyn: Which is so awesome, right? I mean, that is such a feminist thing to be coming out of the mouth of a late 18th-century male. It's just fantastic. Let's go back really quick. You were saying that greatcoats don't really have embellishments, but they do have these layers at the shoulders to keep the rain off. So, is that the difference between a greatcoat and a regular coat? Because we know Bingley wears a blue coat. Would that be different? Would that not be the same as a great coat?

Kristen: The greatcoat doesn't have to have capes, but it usually had at least one. And then there are parodies where it has up to five. So, the coat—Bingley's blue coat would just be his normal—the coat that he would have worn over his waistcoat, just your normal everyday garb. You can't be showing your chemise, your shirt. So, you can't be just in your waistcoat or your vest. You have to be wearing a jacket in company all the time—what we would call a jacket, so a coat. So, his coat is just blue. That's probably just his normal one. And then the greatcoat is this overgarment that's a practical thing that you wear in weather.

Breckyn: And what would women have been wearing? They would have been wearing—you said there's not really an equivalent of the greatcoat for women, right? Are they just not expected to go out in the rain ever?

Kristen: They do have some outer—there are some outer garments for women. So yes, the muslin that was mostly worn—even if you're still wearing silk as a woman during this time, everything is just a lot thinner and there are a lot less layers that you have on, so it's just colder than you would have been before this time. And really, it looked nude—like when our grandmothers looked at mini-skirts and just thought that was just horribly naked. And, so, it was a lot thinner. So that's something that made the shawl very popular—not only did it look like classical drapery, but it also was more—you needed a wool shawl to wear over your thinner dresses.

And then you could—there are outer garments, things called the pelisse, which is a long coat. Actually, there's an extant version that we are pretty sure was worn by Jane Austen herself. And then there are two that are modeled off of male clothing of the time. So, there's one called a redingote or a riding coat. And it was usually militarily styled with epaulettes on the shoulders, perhaps, or double rows of buttons. It just looked very military. And also, those were—instead of being gotten from the dressmaker at the time, the lady's dressmaker, those would have still been made by tailors, even for women. So, that was a difference between other women's garments. And then the other thing was the spencer, which—that only comes to the empire waistline of the neoclassical gown. So, it's in line with that very short bust area. And it was named after Earl Spencer. And there are two urban myths as to how that would have come about. And one was that he was hunting, and he got his coattails caught in some brambles, and so he ripped the tails off. The other one is that he was standing in front of a fireplace and singed the tails, and so he took them off. Neither of those might be true, but it's named after him.

Breckyn: But isn't the spencer just for women, or was it also for men?

Kristen: No, men were also wearing short coats, but they didn't catch on as much as the—in the 1790s, there was a short, fashionable period for short jackets without tails for men, but it just stuck around for women.

Breckyn: So, what about babies and toddlers? They don't actually come up very much in Austen, right? She doesn't really mention children very often. But during her time, the boys—baby boys and toddlers—would wear dresses and nightgowns that look to a modern eye—look a little more feminine. So, were there gendered clothes for babies, or did they not really become gendered until they were older?

Kristen: There were not gendered clothes for babies, so they would have worn gowns—all of the children would have worn gowns when they were little. And then the boys were “breeched,” or put into breeches or britches, when they were between five and seven. And it could be a ceremony, too—that it was a thing that happened. It showed that a boy had gotten to a certain age. There was, for a time, starting in the 1790s through about the 1830s, though, that there was a middle ground. When the boys turned five or seven, they might be given a skeleton suit, which were pants that were buttoned to a short jacket. So, the top and the bottom were buttoned together, and they might have rows of buttons down the front. It was a very comfortable thing for the boys to wear. It got them into pants, but you didn't have to worry about belts or the boys keeping their pants up because it was to the bottom.

Breckyn: Like a "onesie," almost.

Kristen: It's like a onesie. And then they would have worn those probably until they were about 10 or 11. And then they would have gone into what the adult men were wearing, which were at the beginning of the era, pants that ended at the knees, and then by the end of the era were long pantaloons that came to the feet.

Breckyn: And so, did all of this represent just so much work for the servants of the house? Like, muslin, you said it's not very practical. Does it get dirty really easily? Is there a lot of laundry that needs to be done?

Kristen: That's one of my favorite things about that Longbourn novel—

Breckyn: By Joe Baker.

Kristen: Yeah. That Elizabeth is so celebrated for showing up at Netherfield with her petticoat six inches deep in mud. "You go, girl. You just ran across and got dirty and weren't afraid of it." But in Longbourn, it's like, no, there's someone who actually has to get the mud out of her petticoats. Terrible, terrible job. So, you kind of have to not be so proud of Elizabeth after you think about it from that—

Breckyn: Kind of a thoughtlessness towards her servants. Okay. When you watch Austen adaptations or other period films, Kristen, do you notice anachronisms in the fashion and the furniture? Does it drive you nuts?

Kristen: It does. It does drive me nuts. However, there's not a way to get everything completely authentic, and it's got to be on a continuum of how authentic things can be. Because, unless you're going to have people hand weaving the fabric and then hand sewing everything, there's just not time to do it as it would have been completely done. In Chicago, at the Jane Austen Society of North America AGM, Alyssa Opishinski, who is a clothing historian, did a great presentation on how it's impossible to get things completely historically accurate, and so the decisions that are made, and how those are important to any given production, which was very enlightening, and I appreciate her work in that. The other thing is, when you go and look through fashion plates of the time, there's a bunch of different—subtle differences in hairstyles, and some of them are still compatible with our particular aesthetics that we're looking at today. I don't mind different kinds of hairstyles, but I want it to look flattering on the women. I can’t even watch the Persuasion with—

Breckyn: I knew you were going to say that. Is it when her hair is in her face all the time?

Kristen: Those tight little curls stuck to her—ugh.

Breckyn: I feel that way about Fanny in the Emma Thompson Sense and Sensibility, where she just has curls glued to her forehead. She's evil and unlikable though, so it's good for her to have a bad hairstyle.

Kristen: I think that was an intentional way to make her look out of touch with everything. And then the new Emma, the 2020 Emma, her 1980s frizz perm curls. It drives me absolutely crazy. And also, that Emma, too, of Mrs. Elton—them showing her an outlier by putting her in late 1820s, early 1830s clothing and hair. That drove me crazy, too, because that was just an anachronism too far.

Breckyn: She's like a time traveler from the future.

Kristen: Yes. So out of touch that she's coming in from another era, and an era which I purport—and I have discussions with friends of mine who love 1820s and '30s things—that no one looks good in that hair. A lot of people do do it right. I will say that sets are often done very well. I'd hardly ever have a quibble with the furniture and the settings. I live with a classical guitarist, though, and the music often drives him batty.

Breckyn: Yeah, if it's not historically accurate.

Kristen: Yeah, or if it's not even pretending to try to be historically accurate. The saxophone music in the 1980s Northanger Abbey is just a bridge too far.

Breckyn: That's really—ever since you mentioned that, when we were talking earlier—that's something that I really want to look up and go back and listen to. You help run the Costume Society of America. Do you have some Regency costumes yourself? Do you have any bits of Austen-esque clothing?

Kristen: I do. I am an historian, not a maker. And so, even though I am the executive director of Costume Society of America, I don't actually produce clothing. So, I do have help with seamstresses and sewers and makers who—we work on a—I take fashion plates from the time, and we come up with a design, and then they make them for me. My problem, though, is that I—so I do go in garb to the ball at the AGM every year. And so the only dresses that I have had made are ball gowns. I don't have any day dresses.

Breckyn: So, do you not sew or embroider, or have any of those little feminine accomplishments?

Kristen: I have crazy quilted in the past and cross-stitched in the past. I have an astigmatism, so I cannot see in a straight line. Anything that requires you to see in a straight line, I cannot do.

Breckyn: Okay. You would have been kicked out of the drawing room.

Kristen: Yeah.

Breckyn: Kristen, thanks so much for talking to me today. This has been a lot of fun.

Kristen: Thank you.

Breckyn: So, if listeners are interested reading the complete write-up of Kristen's presentation, they can find it on Persuasions Online, which is JASNA's digital peer-reviewed journal. It's titled, "Gender and the Decorative Arts in Austen's Novels." Kristen, where can people find the Costume Society online?

Kristen: You can find Costume Society of America at costumesocietyamerica.com. No "of": costumesocietyamerica.com.

Breckyn: Great. Do they have events during the year, or do they have online things that people can participate in?

Kristen: We do. We have a series of online webinars about twice a month, and you can find it under the News and Events tab—the upcoming virtual events. We have six regions around the country, and they all put on regional events as well. You can find information about that on our website. We also have a YouTube channel with over 75 videos that you can watch of the recordings of the webinars that we've done so far.

Breckyn: Go look up greatcoats, people. Go look up spencers. Yeah, that sounds great. Thank you so much, Kristen. This has been a really fun talk.

Kristen: Thank you.![]()

Breckyn: Now it's time for "In Her Own Words," a segment where listeners share a favorite Austen quote or two.

Melita Repp: Hi, my name is Melita Repp, and I am a member of JASNA's Southern Arizona Region in Tucson, Arizona. One of my favorite quotes—and I have many—is from Mary Crawford in Mansfield Park, when she keeps Fanny's mare longer than she should.

"My dear Miss Price, said Miss Crawford, as soon as she was at all within hearing. I am come to make my apologies for keeping you waiting. But I have nothing in the world to say for myself. I knew it was very late and that I was behaving extremely ill. And therefore, if you please, you must forgive me. Selfishness must always be forgiven, you know, because there is no hope for a cure."

Jane Austen is telling us we need to listen when people tell us who they are. This is Mary Crawford telling us exactly who she is and that she isn't changing. Fanny gets it. Edmund does not. It is said in such a light, witty manner that Edmund mistakes it as part of her charm, feeding into it by asking Fanny to give up the mare the entire next morning.

"She has a great desire to get as far as Mansfield Common. Mrs. Grant has been telling her of its fine views, and I have no doubt of her being perfectly equal to it."![]()

Breckyn: Hello, dear listeners. I just wanted to ask you a favor. If you've enjoyed listening to Austen Chat, please give us a five-star review on Apple Podcasts and leave a comment saying what you like about the show. The more positive reviews we get, the more people will see and hear about the podcast, and the more Austen fans we'll find to join our community. Though Emma Woodhouse may have disagreed, I side with Mr. Weston, "one cannot have too large a party" or too many Janeites. Also, just a reminder to follow JASNA on Facebook and Instagram for updates about the podcast, or to send us a line at our email address, podcast@jasna.org, if you have any comments, questions, or suggestions.

[Theme music]