Jane Austen humorously satirized many aspects of English life, including the church and clergy. Austen’s novels all include clergymen, ranging from the conscientious heroes Henry Tilney, Edward Ferrars, and Edmund Bertram to self-centered Mr. Collins, socially ambitious Mr. Elton, and gluttonous Dr. Grant. Satirical cartoons of the time, like Austen’s portrayals of Collins, Elton, and Grant, illustrate popular perceptions of the clergy and many of the issues facing Austen’s Church of England. Jane Austen mentions such cartoons twice in her letters. In her novels, she sometimes reflects the same criticisms as the cartoons while at other times softening or even countering them.

Austen herself was a deeply committed Anglican Christian. A member of a clerical family, she attended regular worship, read sermons and devotional works, wrote beautiful prayers, and practiced charity to the poor. Her satires came out of a deep love for the church. As Peter Leithart writes,

some of the most severe satire of the clergy in church history has come from devout Christians incensed at the abuses of their leaders. Like them, Austen attacks false clergy not to destroy clergy; she attacks false clergy to defend the true. (33)

Irene Collins adds,

Of one thing we can be quite sure: she meant no harm. She had no wish at all to undermine people’s respect for the church or their faith in the doctrines it preached. . . . Like many members of the Church of England both then and now, Jane Austen looked upon the imperfections and absurdities in the behaviour of the clergy with tolerant amusement. (“Displeasing Pictures” 109–10)

Austen’s satire was meant not to attack the church but to encourage improvement and to entertain.

Austen mentioned at least ninety clergymen in her letters and knew even more (Collins, “Displeasing Pictures” 110). Some relatives and friends appreciated her fictional depictions of the clergy, while others did not. She wrote that her godfather Rev. Cooke and his wife “admire Mansfield Park exceedingly . . . and the manner in which I treat the Clergy, delights them very much” (14 June 1814). In contrast, the Rev. Sherer, vicar of Godmersham, who had read Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, and Emma, was “[d]ispleased” with her “pictures of Clergymen” (Later Manuscripts 236, 703n12). A Mrs. Wroughton, possibly a clergyman’s wife, complained about Emma that she “[t]hought the Authoress wrong, in such times as these, to draw such clergymen as Mr Collins & Mr Elton” (LM 238, 705n34).

What did Mrs. Wroughton mean by saying that Austen should not show clergymen negatively “in such times as these”? As Irene Collins points out (“Displeasing Pictures” 109), when Emma was published at the end of 1815, England had recently finished a long war with France sparked by the French Revolution, which had started with attacks on the church and clergy. The extreme violence and social upheaval in France terrified many in England, and they connected it with neglect of the church. In England, the church and clergy were considered a bulwark keeping the nation stable. Some, then, considered attacks on the church to be attacks on the nation. Those who saw major problems in the church, however, including both Austen and the caricaturists, believed those problems still needed to be addressed.

Austen, the print shops, and satirical progresses

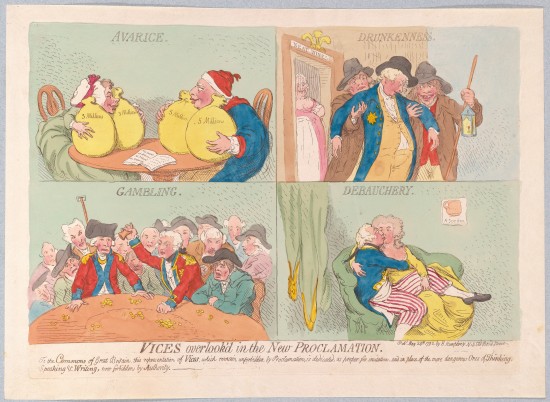

Satirical cartoons were wildly popular in Austen’s England. Jocelyn Harris argues that Jane Austen was “intrigued by the low art of caricature. . . . Austen could not have missed the lampoons so prominently displayed in London streets” (224–25). Print shops in areas where Austen walked featured satirical cartoons by artists such as Thomas Rowlandson, James Gillray, and Isaac Cruikshank. As Harris points out, Austen satirized some of the same problems they caricatured. Gillray’s Vices Overlook’d in the New Proclamation (1792), for example, responded to the Royal Proclamation Against Seditious Writings and Publications, showing the royal family practicing vices the proclamation did not prohibit: the greedy King and Queen, the drunken Prince of Wales, the gambling Duke of York, and the sexually immoral Duke of Clarence (Harris 228).

Vices Overlook’d in the New Proclamation (1792) by James Gillray.

Courtesy of The Beinecke Rare Book Library, Yale University.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Austen depicts these same vices in, for example, greedy John and Fanny Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility, drunken Tom Bertram in Mansfield Park, gambling Wickham in Pride and Prejudice, and sexually immoral Willoughby in Sense and Sensibility. Though she probably did not get her ideas from satirical prints, Austen did address similar issues. In novels, of course, she could present more well-rounded characters and contrast flawed clergymen with better clergymen in ways cartoonists could not.

Many satirical prints sold well for years, in various versions. Print shops sold a range of satirical cartoons. Many cartoons satirized politics and aristocratic scandals. Customers also bought lewd prints for entertainment. Other satirical prints reflected and reinforced popular prejudices and stereotypes. In the eighteenth century, however, William Hogarth (1697–1764) introduced graphic social satires with moral messages (Alexander 8–10). Hogarth popularized satirical “progresses,” probably basing his titles on Bunyan’s A Pilgrim’s Progress. His first such series, A Harlot’s Progress, shows an innocent country girl arriving in London, being drawn into prostitution by a plump brothel keeper, going through stages of misery, and finally dying of syphilis at age twenty-three (Scull 15–16).

A Harlot’s Progress, Plate 1 (1732), by William Hogarth.

Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Jane Austen was obviously familiar with this series and even imagined herself in it. At the age of twenty, she joked in a letter that, if she arrived in London on her own, she would “inevitably fall a Sacrifice to the arts of some fat Woman who would make [her] drunk with Small Beer” (18 September 1796; 373n4). Hogarth’s later A Rake’s Progress and Marriage A-La-Mode were also intended as warnings, showing disastrous social paths to avoid. Maria Bertram’s story in Mansfield Park reflects the latter series, in which a couple marries for money, not love, and adultery helps destroy their marriage and their lives.

Satirizing clerical pride and ambition: A clerical progress

Many satirical cartoons of Austen’s era attacked the clergy as self-seeking, proud, greedy, gluttonous, and even immoral, and criticized the church for being sleepy and inequitable. Some cartoons are dark and tragic, like Hogarth’s progresses; others are light and funny, like the Dr. Syntax series, which Austen mentioned in a letter (2–3 March 1814). Austen’s novels highlight similar issues through light satire: Mr. Collins, Mr. Elton, and Dr. Grant are not evil but comic. (The worst action of one of these clergymen may be when Mr. Elton refuses to dance with Harriet.)

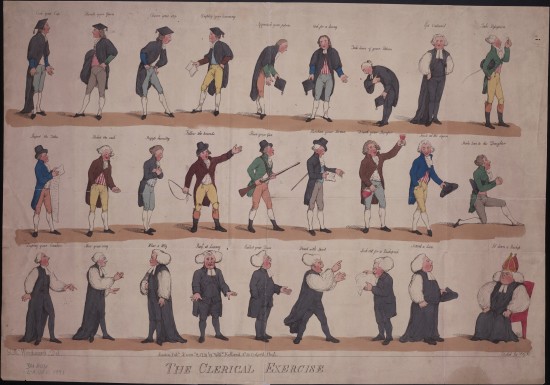

The Clerical Exercise (1791), by George M. Woodward.

Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Mr. Collins, Mr. Elton, and Dr. Grant all reflect popular images of the clergy shown in George M. Woodward’s The Clerical Exercise (1791). In Woodward’s satire, a light variation on Hogarth’s earlier progresses, twenty-seven figures depict a clergyman seeking worldly advancement rather than serving God or the people he is supposed to shepherd. First, as a student at Oxford or Cambridge, the clergyman shows off his cap and gown and his learning. He then approaches his patron with a bow, asks for a living (a position as rector or vicar of a parish) with cap in hand, and, with a lower bow, takes leave of his patron. With a proud air, he is ordained and takes possession of his living. He inspects the tithes (his income), pockets the money, and professes humility.

Austen’s Mr. Collins, “a mixture of pride and obsequiousness, self-importance and humility” (PP 78), reflects this popular conception of the clergyman who pretends to be humble but actually thinks highly of himself. Mr. Collins proclaims that the office of a clergyman is “‘equal in point of dignity with the highest rank in the kingdom—provided that a proper humility of behaviour is at the same time maintained’” (109). Mr. Collins’s sense of clerical duties also partially matches Woodward’s satire:

“The rector of a parish has much to do.—In the first place, he must make such an agreement for tythes as may be beneficial to himself and not offensive to his patron. He must write his own sermons; and the time that remains will not be too much for his parish duties, and the care and improvement of his dwelling, which he cannot be excused from making as comfortable as possible. And I do not think it of light importance that he should have attentive and conciliatory manners towards every body, especially towards those to whom he owes his preferment.” (113)

Austen is not criticizing tithes here, which provided her father’s and brothers’ incomes. Instead, she is satirizing clergymen who put their incomes above their other responsibilities. And of course, although Collins makes readers laugh with his foolishness, he is more than a flat cartoon character. In a novel, Austen can develop him into a three-dimensional character with his own story: his “illiterate and miserly father” (78), his desire to make things right with the family whose estate is entailed on him, and his adventures in seeking a wife. But he also reflects the stereotypical pride, obsequiousness, and focus on money shown in the cartoon series.

To move up in the church, a clergyman needed to make connections with gentry who could assign church livings. One way to do this was to join in their occupations, especially the hunt. After pocketing the tithes, the cartoon clergyman goes on to “follow the hounds” and “poise [his] gun,” hunting like many country “squarsons”: parsons who lived like squires, thus squire-parsons (or “buck parsons”). An estimated twenty per cent of country parsons were “squarsons” (Virgin 110). Among Austen’s clergymen or aspiring clergymen, Edmund Bertram hunts (MP 212) and Henry Tilney owns guns and hunting dogs (NA 188, 219). Her clergyman-brother James Austen also enjoyed the sport. In Persuasion, however, when Charles Hayter gets a living in good hunting country, Charles Musgrove says he won’t appreciate it because he is “‘too cool about sporting’” (236). By the time Persuasion was written, expectations of country clergymen were beginning to change because of Evangelical influence, and squarsons were somewhat less common (Collins, 116).

Clergymen also tried to impress others with their sermons. Henry Crawford, for example, thinks he would like to be an eloquent preacher to earn “the highest praise and honour” (MP 394). While Mr. Collins talks about the duty of writing his own sermons, this effort could be difficult for clergymen, who received no specific training in writing or preaching sermons. Woodward tells his young clergyman, “Purchase your sermon.” Many clergymen did preach sermons written by others (Jacob 258). Mr. Collins mentions that Lady Catherine has approved of the two sermons he preached before her in recent months (PP 74)—implying that he only wrote two sermons himself and read the rest from collections (Collins, Parson’s Daughter 52–53). (The other possibility, that Lady Catherine did not often attend church, seems unlikely, since appearances as well as control of the clergyman and parishioners were important to her.) Mary Crawford says in Mansfield Park that a clergyman should “‘have the sense to prefer Blair’s [sermons] to his own’” (108)—to preach from the published sermons of someone like the renowned Scottish clergyman Hugh Blair. Since Austen had the irreligious Mary Crawford commend this practice, she herself may not have thought highly of a clergyman’s buying sermons.

The worldly clergyman seeks social as well as ecclesiastical advancement. His next steps are to “drink [his] bumper” (a cup or glass of wine filled to the brim), smile at the squire, and “make love to his daughter.” Shades of Mr. Elton—“drinking too much of Mr. Weston’s good wine” and then “making violent love” to Emma in the carriage (E 139, 140). Like the cartoon clergyman, Elton seeks to marry the squire’s daughter in order to move up in society.

Woodward’s final row of figures could represent Mansfield Park’s Dr. Grant, progressing in the church hierarchy. The clergyman shows off in the pulpit and “rail[s] at Luxury”—as he grows obese. He collects higher tithes, probably from an additional church living, and “preach[es] with spirit”; Dr. Grant likewise preaches well (MP 131). Woodward’s clergyman makes social connections at a levee; Dr. Grant’s connections also move him to a higher church position: “through an interest on which he had almost ceased to form hopes, [he] succeeded to a stall in Westminster” (542). While Woodward’s clergyman becomes an arrogant bishop, Dr. Grant does not get that far, though he gains a prebendal stall at Westminster, a cathedral sinecure with increased income. His promotion ironically leads to his death “by three great institutionary dinners in one week” (543). Here Austen gives a darker comic ending than the cartoon does, implying criticism of wealthy, overindulgent men in high church positions.

Gluttony, greed, and tithe pigs

From Dr. Grant, and from popular perceptions, Mary Crawford makes a generalization about clerical gluttony, saying, “‘A clergyman has nothing to do but to be slovenly and selfish—. . . the business of his own life is to dine’” (128). Edmund protests, “‘There are such clergymen, no doubt, but I think they are not so common as to justify Miss Crawford in esteeming it their general character’” (129). Mary admits that Dr. Grant has many good points, saying, “‘Dr. Grant is most kind and obliging to me, . . . really a gentleman, and I dare say a good scholar and clever, and often preaches good sermons, and is very respectable” (130). We see Dr. Grant’s true kindness when Fanny is caught in the rain and he goes out himself with an umbrella to convince her to come in (240). But Mary adds that she sees him as “‘an indolent selfish bon vivant, who must have his palate consulted in every thing’” (130). Among Austen’s clerical characters, only Dr. Grant is clearly gluttonous, though Mr. Collins also enjoys eating (PP 73, 94, 184). So Austen softens the stereotype of gluttonous clergymen, implying, as Edmund says, that “‘there are such clergymen, but . . . they are not so common.’”

Fast Day (1799), by Thomas Rowlandson.

Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book Library, Yale University.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Many satirical cartoons, however, reflect this prevalent stereotype. Thomas Rowlandson’s print Fast Day (1799) shows a group of self-indulgent clergymen, like Dr. Grant, feasting on a church day of fasting. A paper on the floor, headed “A New form of Prayer,” lists culinary delicacies. A servant carries a pig into the room, no doubt representing the “tithe pig.”

Clerical gluttony was often connected with tithes, which provided most of the clergyman’s income. (Revenue from glebe farmland belonging to the living and fees paid for services like weddings and funerals made up the rest.) People of a parish were legally required to pay their rector ten percent of their agricultural produce. This tithe might be paid in kind—pigs, chickens, wheat, eggs, etc.—or in equivalent cash (Collins, Clergy 49–50).

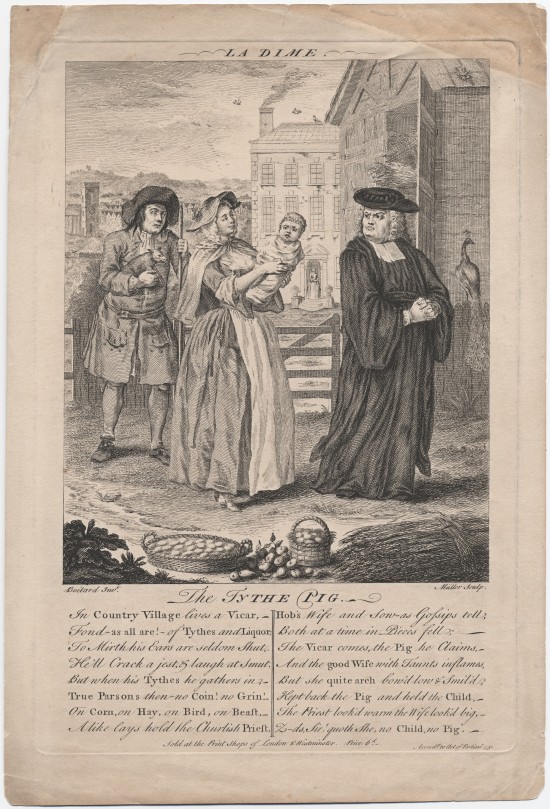

As represented in popular prints, such tithes could be a hardship for poor families. A 1751 satirical print by Louis Peter Boitard, The Tythe Pig, shows a scowling priest who has come to take a tithe pig—the tenth pig produced on a family’s farm. The wife tries to hand him a baby instead, saying, “no Child, no Pig”—they cannot afford to feed all their children if they give the clergyman the pig. This illustration and story were widely copied in the following decades, even appearing on mugs and as porcelain figurines.

The Tythe Pig (1751), by Louis-Philippe Boitard.

Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Tithe Pig (1786), by Thomas Rowlandson.

Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

In Rowlandson’s 1786 print, Tithe Pig, a church clerk and an overweight, gouty clergyman with his foot propped up inspect a pig while a poor farmer awaits their verdict. Such images implied that the clergy oppressed the poor. While Mr. Collins does not detail the responsibility among the clergyman’s “parish duties” (113), it was the clergyman’s duty to see to the care of the poor of his parish. In Emma, Austen softens the stereotype of the clergyman only interested in tithes, since even ambitious Mr. Elton visits the poor (94) and discusses how to provide for “‘old John Abdy’” (416), the impoverished former church clerk.

Rectors, vicars, and curates

While all parish clergymen had similar duties, their incomes differed widely. Richard Newton’s A Clerical Alphabet (1795) contrasts overweight and underweight clergymen in a kaleidoscopic view of popular conceptions. Newton (1777–1798) drew caricatures for William Holland’s print shop in Drury Lane from the age of fourteen until his death from typhus at twenty-two. He produced almost four hundred pictures during this short period (Alexander 9). Like many prints of the time, A Clerical Alphabet was a collaboration: the legend along the bottom says that “Mr. W––n” came up with the idea and wrote some of the items, while Holland wrote the rest, and Newton drew the pictures.

A Clerical Alphabet (1795), by Richard Newton.

Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

The cartoon attacks a whole range of clerical issues, including inequalities among the clergy, ignorance, dullness, pride, and laziness, as well as the opposite extreme of excessive emotionalism. The text reads:

A Was Archbishop with a red face,

B Was a Bishop who long’d for his place.

C Was a Curate, a poor Sans Culotte,

D Was a Dean who refus’d him a Coat

Even grudged him small beer to moisten his throat.

F Was a Fellow of Brazen-Nose College1

G Was a Graduate guileless of knowledge

H Was a high-flying Priest had a call!

I Was an Incumbent did nothing at all.2

K Was King’s Chaplain as pompous as Dodd,3

L Was a Lecturer4 dull as a clod.

M Was a Methodist Parson, stark mad!

N Was a NonCon5 and nearly as bad.

O Was an Orator, stupid and sad.

P Was a Pluralist ever a-craving

Q A queer Parson at Pluralists raving!

R Was a Rector at Pray’rs went to sleep

S Was his Shepherd who fleec’d all his sheep.

T Was a Tutor, a dull Pedagogue

U Was an Usher delighted to flog.

V Was a Vicar who smok’d and drank grog.

W Was a wretched Welch Parson in rags.

X Stands for Tenths or for Tythes in the bags.

Y Was a young Priest the butt of Lay Wags.

Z Is a letter most people call Izzard

And I think what I’ve said will stick in their gizzard.

This cartoon again attacks tithing. Clergymen were supposed to shepherd their congregations, but S, the shepherd who works for R, the rector, is busy “fleecing” them instead. In a 1795 Newton cartoon, An Old Grudge, a fat parson tells the devil, “‘You shan’t have a sheep out of my fold till I fleece ’em myself.’”

The “alphabet” shows different types of clergymen, which Austen assumes her readers would recognize. Rectors, vicars, and curates received different levels of tithes (White 13). Mr. Collins has “a very good opinion of himself, of his authority as a clergyman, and his rights as a rector” (PP 78). The rector received all the tithes from his parish, though that was not always a sufficient income. Colonel Brandon offers Edward Ferrars “‘a rectory, but a small one,’” worth only around two hundred pounds a year (SS 320).

Mr. Elton of Emma, however, is a vicar (V). While Newton’s cartoon vicar is prosperous, vicars received only certain portions of the tithes (usually the animal products), on average only about a quarter of the income a rector would get. Someone else, possibly the local squire, a university, or a cathedral, was the nominal rector and took most of the tithes (Collins, Clergy 51). Austen intentionally makes Mr. Elton a vicar with a lower income, rather than a rector, and shows the poverty of Mrs. Bates, the previous vicar’s widow. While Elton has some private income, Emma misses the clues that he will probably need to marry for money.

The lowest rung of country clergymen was the curate (C), who was paid a minimal stipend. Newton pictures him thin and without pants (“sans culotte,” like a peasant in the French Revolution). In Austen’s “The Generous Curate,” the title character has “nothing to support himself and a very large family but a Curacy of fifty pound a year,” so he cannot be as generous as he wishes to be (Juvenilia 95). Austen reflects a popular and valid image: most curates at the time earned fifty pounds a year or less, barely enough for survival (Hart, Curate’s Lot 127).

Pluralists, incumbents, and curates

There were many poor curates because of pluralism, the practice whereby clergymen held multiple church livings. About a third of clergymen were pluralists like Newton’s P, who holds a church on his head and two under his arms (Collins, Clergy 29). In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth wonders why Mr. Collins and Charlotte spend so much time at Rosings, until she realizes that “there might be other family livings to be disposed of” (190). Mr. Collins is hoping Lady Catherine will make him a pluralist like the one in the cartoon, rich with livings and even more self-satisfied than he is already. Charlotte also looks for possibilities of extra livings elsewhere. She hopes for a match between Elizabeth and Darcy because he has “considerable patronage in the church” (203), and, once the match is made, Mr. Bennet points out to Mr. Collins that Darcy “has more to give,” meaning more church livings at his disposal (424, 539n).

Austen did not necessarily consider pluralism an evil. Her father was a pluralist, holding the livings of Steventon and Deane. The parishes were small and adjacent; he needed the income and easily served both (Cass 57, 60). Most pluralists, however, lived in one of their parishes and hired poorly paid curates to serve the others where the pluralist was “non-resident” (Jacob 71). In Mansfield Park, Henry Crawford assumes that Edmund will not live at his Thornton Lacey parsonage, but Edmund says, “‘I have no idea but of residence’” (287). His father explains that only a resident clergyman can meet his parishioners’ needs and give them a good example (288). Austen here makes a strong statement against pluralism with non-residency. At the end of Mansfield Park, however, Edmund becomes a pluralist—he takes the living of Mansfield along with that of Thornton Lacey (547). Thornton Lacey is eight miles away, close enough for Edmund to ride there on a Sunday, but he cannot reside in both parishes. While the cartoonist lampoons pluralism, Austen shows the realities of England’s church system, as well as the ideals. For a clergyman to live as a gentleman with a family, he often needed more than one church living (Jacob 101).

A Worldly Bishop and a Godly Curate (1810–1820).

Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Many cartoons satirize inequities in the church by exaggerating the poverty of curates and contrasting them with wealthy clerics. A Worldly Bishop and a Godly Curate (Anonymous, 1810–1820) shows a poor curate doffing his hat to a fat bishop. In Persuasion, Charles Hayter is a curate, with an income too low to marry Henrietta Musgrove. Austen satirizes prejudices against curates by having snobbish Mary Musgrove call Charles “‘[n]othing but a country curate’” (82). Arrogant Sir Walter Elliot also dismisses Wentworth’s brother: “‘Oh! ay,—Mr. Wentworth, the curate of Monkford. You misled me by the term gentleman. I thought you were speaking of some man of property: Mr. Wentworth was nobody’” (26). He also despises another man—Lord St. Ives—as the son of “‘a country curate, without bread to eat’” (22). Similarly, a later cartoon, Charles Williams’s Feasting Scraps (1824), shows a curate and his family “feasting” on dry bones and “meagre fare” contrasted with an image of a “bloated vicar” dining with his well-fed company; the vicar “preaches Humility, his practice pride.”

A Pic Nic

A Tuck Out

From Feasting Scraps (1824), by Charles Williams.

Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

A curate like Mr. Wentworth or Charles Hayter was often a temporary assistant to a rector or vicar, while the curate waited for his own living (Hart, Curate’s Lot 103). Mary Crawford claims that Dr. Grant’s curate “‘does all the work’” (MP 128), even though Dr. Grant lives in the parish. Henry Tilney has a curate who serves his church when he is in Bath or at Northanger (NA 229). However, as Easton points out in her discussion of Henry Tilney’s diligence as a clergyman, the “two or three terriers” (NA 219) that accompany Henry as he receives his visitors at the parsonage door indicate that he is “committed to this residence,” since the terriers will patrol his land “protecting domestic egg-layers and grain piles from pesky vermin” (Easton 159). Once Henry gets married, he and Catherine will no doubt live full-time in the parsonage.

With the letter I, Newton shows an Incumbent who “did nothing at all.” The incumbent of a living held his job for life. When he could no longer work—or if he did not wish to work—he hired a curate but still received most of the income himself (Jacob 70). Henrietta Musgrove of Persuasion hopes that “their dear Dr. Shirley,” rector of the parish church, “who for more than forty years had been zealously discharging all the duties of his office, but was now growing too infirm for many of them,” will retire and give Charles the curacy of Uppercross (84). Likewise, when Austen’s father retired, he moved to Bath and gave his son James the curacy of Steventon. When their father died, James got the living, and Jane and her mother and sister lost the income that had supported them (Collins, Clergy 128). So, when Jane wrote about Dr. Shirley and the curate who wanted to take his place, she may have been thinking of her father and her brother’s situation.

Dr. Syntax, Cartoon Country Curate

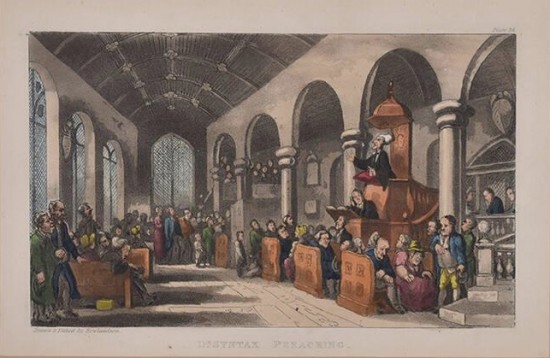

Dr. Syntax Preaching (1811), by Thomas Rowlandson.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Dr. Syntax was a famous fictional curate, familiar to Jane Austen. She wrote in one of her letters, “I have seen nobody in London yet with such a long chin as Dr Syntax” (2–3 March 1814). Caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson created Dr. Syntax, a poor clergyman who journeys around England, falling into one scrape after another. Author William Combe added Syntax’s story in a narrative poem, which was published with Rowlandson’s cartoons; sequels followed. In the first book, Dr. Syntax is a curate who has given up on getting a decent living from “That thankless parent, Mother Church” and feels that he must be content “with drudging in a Curacy” (1). Syntax declares, “I feed the flock, while others eat / The mutton’s nice, delicious meat” (8). (In other words, he does the work, while the rector elsewhere gets most of the income.) Syntax goes on a tour, planning to write a book about it and make money. Like Austen’s clerical characters, Dr. Syntax is in many ways a good and faithful parson, with human foibles and failures, such as credulity and overeating when he gets the chance. Dr. Syntax—thin like other curates and driving a horse whose ribs are visible—gets his living in the end through his friend Squire Worthy (263), just as Charles Hayter gets at least a temporary living through a friend at the end of Persuasion. Syntax is welcomed to his new parish, where he preaches, prays, and points the way “to brighter worlds” (266).

Some cartoons showed clergymen as immoral, but Austen does not do that. Rowlandson occasionally attempted to give Dr. Syntax more risqué adventures. Combe, however, respected the clergy and refused to ridicule them, and the publisher Ackermann, who did not want to offend prospective readers, also vetoed these ideas and kept the story wholesome (Payne 283–84).

Sleeping congregations and “enthusiasts”

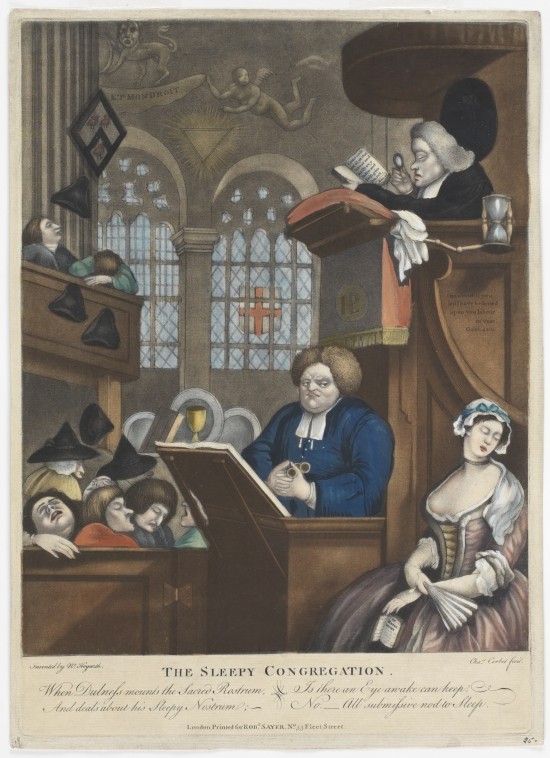

When Dr. Syntax preached during his travels, the squire was so attentive that “neither did he sleep or snore— / A wonder never known before” (186). Many popular cartoons showed clergymen putting their congregations to sleep. In Mansfield Park, Mary believes that clergymen are “‘nothing,’” since their “‘two sermons a week’” do not influence people’s lives (107–08). She sees clergymen as dull and uninteresting, like Newton’s Lecturer (L) and Orator (O). Newton’s Rector (R) even falls asleep himself as he leads the congregation in prayer. Mary (and Austen) may be thinking of similarly dull clergymen.

The Sleepy Congregation (1746–1766), by Richard Purcell.

Copy of The Sleeping Congregation (1736), by William Hogarth.

Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Hogarth satirized such preachers in a 1736 print, The Sleeping Congregation, which was copied and reproduced all the way into the 1800s. (Some versions are called The Sleepy Congregation.) It shows the English church fast asleep, implying that the clergy were not influencing the nation as they should have been. Jane Austen recognized this problem. In Mansfield Park, Henry Crawford and Edmund Bertram discuss how the liturgy can be read, and sermons preached, in ways that “‘touch and affect’” the congregation, rather than putting them to sleep (394). Again, Austen softens the stereotypical image. Henry and Mary believe the stereotype, but Edmund argues that there is “‘a spirit of improvement abroad’” and that preachers are speaking more distinctly and energetically, presumably not putting their congregations to sleep (392–93).

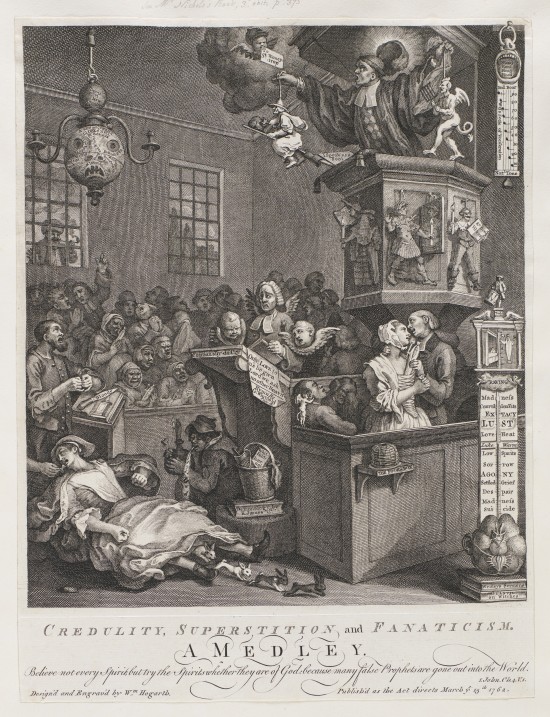

Some types of preachers were known, however, for keeping their congregations wide awake. The Methodists, for example, preached with energy and feeling and had attempted for some years to awaken and reform the Church of England. The Methodists had an exaggerated reputation as wild “enthusiasts” (Hart, Country Parson 72); “enthusiasm” was considered dangerous to the church as it could replace reason with emotion. Cartoons ridiculed Methodists for preaching outdoors, flitting about to preach in various places “like pigeons,” and insisting that people keep the Sabbath. In 1762, Hogarth published Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism, attacking Methodists, Catholics, and charlatans: the wild events happening in the sanctuary prevent the congregation from sleeping.

Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism (1762), by William Hogarth.

Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

These critical attitudes toward Methodists illustrate the confrontation near the end of Mansfield Park as Mary tries to downplay Henry and Maria’s adultery (529). When Edmund confronts her, she ridicules him:

“A pretty good lecture upon my word. Was it part of your last sermon? At this rate, you will soon reform every body at Mansfield and Thornton Lacey; and when I hear of you next, it may be as a celebrated preacher in some great society of Methodists, or as a missionary into foreign parts.” (530)

By associating Edmund with Methodists, Mary accuses him of being too emotional and judgmental in religion, carrying it to excess. Edmund is like the Methodists in being serious about his faith and values, but he is not the wild enthusiast that Mary calls him. Significantly, Austen puts this negative comment about Methodists in Mary Crawford’s mouth. Edmund believes that Mary judges “‘from prejudiced persons’” (129) and that her mind has been “‘corrupted’” (528) by these prejudices. While Mary accepts the false stereotypes that she has heard from others and probably has seen in cartoons, Austen counters those stereotypes.

A serious view

Satire uses humor and exaggeration to point out flaws in people and society. Cartoons graphically picture those flaws. A novel, of course, can give a much more nuanced approach, including both positives and negatives. Austen shows us good clergymen—not perfect people, but decent men who try to do their best. Out of the twelve clergymen mentioned in her completed novels (Edward Ferrars, Dr. Davies, Mr. Collins, Henry Tilney, Mr. Morland, Edmund Bertram, Mr. Norris, Dr. Grant, Mr. Elton, Charles Hayter, Dr. Shirley, and Mr. Wentworth), only three (Collins, Elton, and Grant) are criticized for flaws we see in satirical cartoons, and even those three appear to fulfill their duties as clergymen sufficiently (Collins, Parson’s Daughter 46).

Austen counteracts some of the exaggerations of satirical cartoons with very serious statements in Mansfield Park. Edmund tells Mary that the clergy

“has the charge of all that is of the first importance to mankind, individually or collectively considered, temporally and eternally— . . . the guardianship of religion and morals, and consequently of the manners which result from their influence. No one here can call the office nothing. If the man who holds it is so, it is by the neglect of his duty, by foregoing its just importance, and stepping out of his place to appear what he ought not to appear.” (107–08)

Here we see what Jane Austen thinks of the church and clergy: they have a responsibility for the most important needs of mankind. Cartoonists and Jane Austen satirize clergymen like Dr. Grant who indulge their desires, conform to the world around them, and seek wealth and importance. Austen, however, reminds her readers that such clergymen were not the majority, contrasting them with men like Edward Ferrars, who readily fulfilled “his duties in every particular” (SS 428).

NOTES

2There is no J, since I and J were considered to be the same letter.

3Dr. William Dodd, at one time Chaplain to the King, lived extravagantly and went deep into debt and then forged a bond to clear those debts. When the forgery was discovered, he was tried and hanged at Tyburn in 1777.

4Lecturers preached at city churches on Sunday evenings.

5Nonconformist: member of a denomination outside the Church of England.

IMAGES CITED

- Bickham, George. Enthusiasm Displayed. London, 1739. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:549766

- Boitard, Louis Peter. The Tythe Pig. London, 1751. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:552696. [See also 1770 version https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1861-0518-937; pottery versions https://theprintshopwindow.wordpress.com/2013/03/27/louis-philippe-boitard-the-tythe-pig-1751/.]

- The Carrier, or Methodist Pigeon. London, 1766–1777. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_2010-7081-1504

- Gillray, James. Vices Overlook’d in the New Proclamation. London, 1792. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:4000650

- Griffiths, John. Enthusiasm Displayed. London, 1765. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:4787777

- Hogarth, William. Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism. London, 1762. [Earlier version: Enthusiasm Delineated, 1761.] https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:5240469

- _____. A Harlot’s Progress, Plate 1. London, 1732. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:4048412

- _____. Marriage A-La-Mode. London, 1745. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marriage_A-la-Mode_(Hogarth)

- _____. A Rake’s Progress. London, 1735. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Rake%27s_Progress

- _____. The Sleeping Congregation. London, 1736, 1762; https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:4048579. [Also published as The Sleepy Congregation. Colorized by Charles Purcell, 1746–1766. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:551364]

- Modern Reformers. London, ca. 1763. [Based on Hogarth.] https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:549117

- Newton, Richard. A Clerical Alphabet. London, 1795. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:976843

- ______. An Old Grudge. London, 1795. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1948-0214-355

- Phillips, John. Clerical Humility and Modern March of Piety. London, 1829. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1868-0808-9043

- Rowlandson, Thomas. Dr. Syntax Preaching. London, 1811. https://emuseum.mfah.org/objects/34660/dr-syntax-preaching?ctx=278741e727e0bd04f695695ebeb8396e631f3371&idx=6

- _____. Dr. Syntax, Loosing His Way. London, 1811. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:5235155

- _____. Dr. Syntax Taking Possession of His Living. London, 1811. https://www.artic.edu/artworks/133370/doctor-syntax-taking-possession-of-his-living-from-the-tour-of-doctor-syntax

- _____. Fast Day. London, 1799. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:3997549

- _____ Tithe Pig. London, 1786. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:550178

- _____. A Sleepy Congregation. London, 1811. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:974195

- _____. The Tour of Doctor Syntax. [By William Combe.] London, 1811. http://archive.org/details/tourofdoctorsynt01comb/

- Williams, Charles. Feasting or Feasting Scraps. London, 1824. Includes A Pic Nic and A Tuck Out. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:2803056

- Woodward, George M. The Clerical Exercise. London, 1791. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:550650

- A Worldly Bishop and A Godly Curate. London, 1810–20. https://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:974081