A 1799 novel may have supplied the prototype for one of Austen’s most beloved characters, and its depiction of amateur theatricals might have inspired Austen’s use of Lovers’ Vows in Mansfield Park.

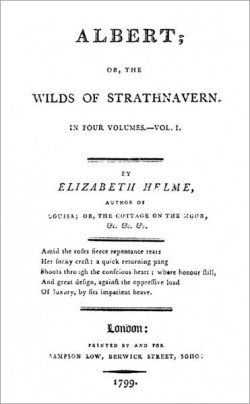

Albert; or, the Wilds of Strathnavern, a novel by Elizabeth Helme,1 is mostly forgotten today, but Helme’s novels were popular in Austen’s time, and some were republished well into the nineteenth century. Albert differs from Austen’s novels in many respects; yet the striking similarities discussed here suggest that Austen drew from Albert for both Persuasion and Mansfield Park.

Albert; or, the Wilds of Strathnavern, a novel by Elizabeth Helme,1 is mostly forgotten today, but Helme’s novels were popular in Austen’s time, and some were republished well into the nineteenth century. Albert differs from Austen’s novels in many respects; yet the striking similarities discussed here suggest that Austen drew from Albert for both Persuasion and Mansfield Park.

Juliet Shields classes Albert; or, the Wilds of Strathnavern with novels that present a romanticized view of the Scottish Highlands (921). The main characters in Albert are two brothers and sisters from different backgrounds: the wealthy Frederic and Gertrude St. Austyn and the poor but virtuous Albert and Marian Montgomery. The Montgomery family must leave the wilds of Strathnavern after a vengeful laird tries to pressure Marian into marriage. Once in London, both parents die, and Albert and his sister are left to fend for themselves.

The other family, the wealthy St. Austyns, live on their estate in the country. Mrs. St. Austyn neglects her children in favor of reading novels. Unbeknownst to her, her son Frederic’s conniving tutor Mr. Berners is busy corrupting his pupil’s morals. When Mrs. St. Austyn is “seized with a rage for private theatricals,” Mr. Berners sees a golden opportunity to secretly court Gertrude (1: 26). The impressionable girl is cast as Juliet to the tutor’s Romeo, and the pair—to borrow a phrase from Austen—are brought into a “dangerous intimacy” (MP 462). This of course is how Austen would use private theatricals in Mansfield Park.

Helme does not develop and explore the possibilities of this scenario to the extent that Austen does. The play-acting is briefly mentioned in a chapter entitled “The Effects of Erroneous Education and Private Theatricals” (1: 24–28). Helme then moves on to the sudden death of Mr. St. Austyn, which frees his widow to move to London with Frederic, Gertrude, and Mr. Berners in tow. Mrs. St. Austyn also dies, but fortunately, her benevolent sister, Mrs. Stanhope, steps in to provide loving guidance to her orphaned niece and nephew.

Likewise, Marian and Albert Montgomery discover that they have a long-lost uncle, Colonel O’Bryen, who bears a striking resemblance to Admiral Croft in Persuasion. Colonel O’Bryen is the brother of Frederic and Marian’s late mother. By the time he appears on the scene near the end of volume 1, Marian and Albert have met Gertrude and Frederic in London, but under unpropitious circumstances. Frederic, under the influence of his tutor, has been carousing all around town and sinking into debt. Frederic falls in love with Marian at first sight, but Berners suggests that since she is poor, he should just ask her to be his mistress. Marian indignantly rejects the offer. Frederic is deeply remorseful, and Albert resents the insult to his sister. When Mr. Berners’s true character is revealed, Gertrude is filled with shame for having accepted his attentions. Later, she falls in love with Albert but concludes that he “merits a woman free from those follies that have disgraced me. I esteem him above all men; but I dare not venture to love him” (3: 99).

Colonel O’Bryen is the deus ex machina who devotes himself to setting everything right. Rich uncles with large fortunes—often acquired overseas in the East or West Indies—were a popular plot device in novels of this time and are found in novels by Tobias Smollett, Helen Maria Williams, Barbara Hofland, Charlotte Smith, and (later) Charlotte Brontë, to name a few.2 Often, rich uncles were merely offstage characters who die in a timely fashion, leaving “wealth . . . magically ‘found’ overseas whenever a novel needs it,” as Franco Moretti explains (27).

Colonel O’Bryen is far from being a mere plot device with deep pockets—in fact, once he appears, he takes over the story. Marian’s charm, Albert’s manly virtue, Frederic’s moral reformation, Gertrude’s girlish timidity—none of this can compete on the page with the outspoken old Colonel’s energetic vitality. We first see him, “an elderly man in military costume” (1: 161), in a tavern at the exact moment when Albert crosses paths with Frederic and his Machiavellian tutor. The colonel interests himself in Albert, and Albert finds him “more inquisitive than strict politeness would allow, but there was a respectability about him, though mixed with eccentricity” (1: 164). The colonel delights in deceiving Albert and then Marian as to his true identity.

Just as the colonel overturns the sentimental decorum of Helme’s novel, Admiral Croft makes us smile every time he strides into the room in Persuasion. His unfiltered remarks sometimes ruffle the feathers of the formal and upright Lady Russell. Admiral Croft’s “manners were not quite of the tone to suit Lady Russell, but they delighted Anne. His goodness of heart and simplicity of character were irresistible” (P 127). Likewise, Frederic and Gertrude’s aunt Mrs. Stanhope finds the colonel a bit disconcerting at times. She reproves him for his aggressive matchmaking and the tricks he plays on the young people: “I thought you had promised never more to offend that way. . . . I see you are incorrigible” (4: 196).

The colonel suspects that his niece Marian is carrying a torch for Frederic, who has broken with his tutor and has vowed to live in poverty until he has repaid his debts. The colonel offers to help him. “Come, come, don’t treat me like a stranger,” he urges, although he is a stranger (3: 12), but Frederic rejects the offer, choosing to exile himself in penance for his behavior.

Admiral Croft resembles the colonel in his total lack of reserve. When Anne Elliot first visits the Crofts in Kellynch Hall, her former home, the admiral doesn’t let delicacy get in the way of discussing the awkwardness of her situation: “‘Now, this must be very bad for you . . . to be coming and finding us here.—I had not recollected it before, I declare,—but it must be very bad.—But now, do not stand upon ceremony.—Get up and go over all the rooms in the house if you like it’” (127). When Anne later comes across the admiral on the streets of Bath, he greets her “with all his usual frankness and good humour. ‘Ha! is it you? Thank you, thank you. This is treating me like a friend’” (169).

The most striking resemblance between the two men’s personalities is their belief that courtship is a simple matter of choosing a pretty girl and popping the question. Both the admiral and the colonel are blithely optimistic about quickly contracted marriages. The admiral, at least, can point to his own fortunate experience. He illustrates the point for Anne Elliot by asking his wife, “‘How many days was it, my dear, between the first time of my seeing you and our sitting down together in our lodgings at North Yarmouth?’” Mrs. Croft demurs: “‘[I]f Miss Elliot were to hear how soon we came to an understanding, she would never be persuaded that we could be happy together. I had known you by character, however, long before.’” The admiral’s reply suggests he did not enquire into his Sophy’s virtues or character before proposing to her, or could even conceive of a reason to do so: “‘Well, and I had heard of you as a very pretty girl; and what were we to wait for besides?’” (92).

Likewise, Colonel O’Bryen urges Albert to make quick work of courtship. “Happy is the wooing, that is not long a-doing,” he admonishes his nephew. “I wonder what the plague you would have. Is she not a charming girl, almost as handsome as Marian? Is she not your friend Mrs. Stanhope’s niece? and has she not a good fortune?” (2: 103). The colonel’s impatience is echoed by Admiral Croft when he can’t understand why his brother-in-law is taking so long to choose a wife: “‘I wish Frederick would spread a little more canvas, and bring us home one of these young ladies to Kellynch’” (P 92). While Admiral Croft uses a nautical term, “spread a little more canvas,” Colonel O’Bryen uses an army metaphor, specifically, from army engineering. After he has tricked Frederic St. Austyn into coming back from exile, he boasts: “you do my ingenuity no more than justice. I am a skilful engineer, and what cannot frequently be effected by open force, may be performed by a little well-applied craft” (4: 179).

And can it be a mere coincidence that both the admiral and the colonel use the expression “breaking a head and giving a plaster” (i.e., injuring someone and then offering them a remedy for that injury)? Admiral Croft points out that Captain Wentworth has literally (if accidentally) broken Louisa’s head: “‘Ay, a very bad business indeed.—A new sort of way this, for a young fellow to be making love, by breaking his mistress's head!—is not it, Miss Elliot?—This is breaking a head and giving a plaister, truly!’” (P 126–27). In Albert; or, the Wilds of Strathnavern, Albert says that he is by nature too stubborn to obey his uncle’s wishes implicitly—but his obstinacy must be a family trait, inherited from his uncle: “That’s what you call breaking my head, and giving me a plaister,” the Colonel retorts, “though to say the truth, I think you are a good deal like me when I was a young man” (1: 154).

There are also some notable differences between the two characters. Admiral Croft is the happiest married man in all of Austen’s novels, while Colonel O’Bryen is a bachelor. The colonel uses vulgarisms like “Zounds,” “What the pie,” and “what the plague.” He enjoys planting kisses of greeting on Marian and Gertrude. He frankly tells his nephew that he wants him to get married so he can get busy making babies. “[I]t would be very comfortable to see a great-nephew or two” (2: 7). I don’t think Admiral Croft would make a ribald joke, as the colonel does when he threatens to marry a young wife himself:

“Don’t go too far, Albert, I am not the first old fool who, horn mad, has got a young wife and an heir to his estate.”3

“A child of your own, Sir, would have the nearest claim to your favour.”

“Z—ds, Sir, I don’t suppose that it would be my own—but answer me pray: do you never intend to marry?” (2: 104)

The two men also differ in the extent of their matchmaking activities. In Albert, the colonel knows that Albert loves Gertrude and Frederic loves Marian, despite their equivocations. He cheerfully presses both courtships along, pushing aside the various impediments that keep the lovers apart and chiding Frederic and Albert for their scruples about declaring themselves: “Zooks, the young fellows of now-a-days have no spirit” (4: 328). He even lies to Gertrude and announces that he and Albert have lost all their money, knowing that this revelation will startle Gertrude into declaring that she loves him anyway. Where romance is concerned, the colonel will take no denials.

In contrast, Admiral Croft has no idea about the thwarted romance of Anne Elliot and his brother-in-law. The admiral is oblivious to the pain he is causing Anne when he talks about finding a wife for Captain Wentworth: “‘I think we must get him to Bath. Sophy must write, and beg [Frederick] to come to Bath. Here are pretty girls enough, I am sure’” (173).

Colonel O’Bryen’s fondness for matchmaking is essential to the happy ending in Albert. Compared to the colonel, Admiral Croft plays a lesser, but still significant, part in the plot of Persuasion. The Crofts’ tenancy at Kellynch Hall is the precipitating event which brings Captain Wentworth and Anne Elliot together after a seven-year separation. We learn from the admiral that “‘We are expecting a brother of Mrs. Croft’s here soon’” (49). Later, he brings a letter from Anne’s sister Mary with the welcome news that Frederick Wentworth will not marry Louisa Musgrove.

Yet, in her first draft of Persuasion, the admiral is the agent—albeit an unsuspecting one—of the loving reunion between Anne and Captain Wentworth. In this version, there is no letter, no declaration that “‘I am half agony, half hope’” (237). Instead, Anne Elliot meets the admiral on the street and he invites her to come visit with his wife: “‘I cannot stay, because I must go to the P. Office, but if you will only sit down for 5 minutes I am sure Sophy will come—and you will find nobody to disturb you—there is nobody but Frederick here’” (259). Anne and Frederick Wentworth struggle to compose themselves as they realize they are going to be alone together, without a moment’s warning. The admiral calls Wentworth aside: “‘As I am going to leave you together, it is but fair I should give you something to talk of’” (260). He tells Wentworth to ask Anne whether it is true—as has been rumored around town—that she is engaged to her cousin, Mr. Elliot. The admiral then departs, and Captain Wentworth, mortified, repeats the question to Anne, adding: “‘The Adml is a Man who can never be thought Impertinent by one who knows him as you do.—His Intentions are always the kindest & the Best’” (262). As Captain Wentworth explains, the admiral wants to assure her that he’ll give up the lease on Kellynch Hall, if Anne and Mr. Elliot plan to live there.

This awkward enquiry gives Anne the opportunity to assure Captain Wentworth that there is no truth to any part of the rumor—she is not engaged to Mr. Elliot. A “silent, but a very powerful Dialogue” follows, the lovers understand each other at last, and are “restored to all that had been lost” (263).

As scholars (e.g., Gemmill) have noted, the set-up for Anne and Wentworth’s moment of truth in Austen’s first draft is—by comparison with the revised version—artificial and contrived. Paul Wray points out that Admiral Croft is never conniving in the rest of the novel, and in this encounter, the admiral is not being forthright with Anne about the reason he wants her to come back to his house: “This dissembler is not the admiral that we know.” This kind of scheming is more in keeping with Helme’s Colonel O’Bryen. Austen’s revised denouement with its famous letter has nothing to do with the admiral; instead, our last glimpse of Admiral Croft is at a social engagement at the Elliots’ home, still unaware of the central love drama in the story. In her brief concluding chapter, Austen assures us of “the prompt welcome which met [Anne] in [Captain Wentworth’s] brothers and sisters” (251).

While I believe I am the first to trace a similarity between Elizabeth Helme’s Albert and Jane Austen’s works, scholars have previously suggested some connections between Helme and Austen. The entrance of the hero in Austen’s juvenile tale Love and Freindship is thought to be a parody of Helme’s first novel Louisa, or the Cottage on the Moor.4 Anthony Mandal compares the instant intimacy of Helme’s characters Louisa and Mrs. Rivers in Louisa with the swift friendship formed between Laura and Sophia in Love and Freindship. He notes: “Austen would no doubt have been aware of Helme’s novel, which was well received by critics” (48). Sarah Salih sees a connection between Helme’s novel The Farmer of Inglewood Forest and Austen’s unfinished fragment Sanditon, both of which feature a young woman of color (331).

Further, in an article in Jane Austen’s Regency World, I have noted that both The Farmer and Sanditon use a carriage accident near the home of a farmer as the inciting event for the action. In both tales, the farmer invites an injured passenger to stay at the farm while he recovers, and, in both tales, the grateful man offers to take one of the farmer’s grown children with him when he leaves. In addition, Austen turns a seductive conversation about sentimental novels in Helme’s novel into comedy in Sanditon, with an exchange between Sir Edward Denham and Charlotte Heywood.

Helme’s novels were widely available at circulating libraries in Austen’s time. As Julie Shaffer notes, Helme’s “immensely popular” novel Louisa, or, the Cottage on the Moor “went through at least nine editions by 1801 in Great Britain and the United States, remaining in print until about 1850, and was translated into French and Russian; given its obvious popularity, this novel and its author deserve to be better known to scholars of late eighteenth-century women's novels than they currently are” (69). Cambridge University’s Orlando database of British women writers says of Helme: “Her novels abound in cliché but deploy their derivative plots, characters, and diction with attractive energy and conviction” (Brown et al.). Albert went through three editions and was translated into French (Brown).

Did Jane Austen draw on Helme’s character of Colonel O’Bryen to create Admiral Croft? The figure of a kindly, generous old duffer is certainly not unique in the annals of literature, and the Critical Review said that Albert contained “little originality,” consistent with the idea that generous old uncles were readily to be found in eighteenth-century novels. However, the specific similarity of the characters, down to the “breaking a head” idiom, as well as the use of private theatricals for covert seduction, makes it seem quite possible that Austen read—and filed away for future use—these aspects of Albert; or, the Wilds of Strathnavern.

NOTES

1Elizabeth Helme’s date of birth is uncertain; her date of death is thought to be between 1810 and 1814 (Watson). See also Brown et al.

2For example, rich uncles share their fortunes in Tobias Smollett’s The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle, Helen Maria Williams’s Julia (1790), Charlotte Smith’s Desmond, A Novel (1792), Barbara Hofland’s The Merchant’s Widow (1814), and Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847). See also Moretti for a discussion of the prevalence of colonial fortunes as a plot device in the fiction of this era (24–28). I am indebted to Susan Allen Ford for the suggestions for eighteenth-century novels and plays featuring rich uncles.

3“Horn mad” is a reference to being cuckolded. The cuckolded husband was traditionally referred to as having horns on his head (Williams).

4See, for example, Alan D. McKillop, who draws attention to the similarity between the following passage in Love and Freindship—“One Evening in December . . . we were on a sudden greatly astonished, by hearing a violent knocking on the outward door of our rustic Cot”—and the corresponding passage in Louisa, or, the Cottage on the Moor: “On a frosty night, the latter end of December . . .—the inhabitants of the cottage were disturbed by a loud knocking, which was answered by a female voice, who from a window in the upper story demanded the reason of this late alarm!” (McKillop 35).