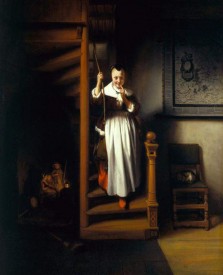

I describe King George IV as Jane Austen’s royal fan. This is the man known generally in Austen literature as the Prince Regent because he didn’t ascend to the throne until after her death. He was not highly regarded, either as the regent or the monarch. He ran up great personal debts, he launched massive building projects, and he had a reputation for gluttony in all things. A satire made of the king at the end of his reign, Great Joss and His Playthings, shows the image of the king as a deluded, drugged-up spendthrift with absurd building projects everywhere, with his giraffe, with his toy soldiers—and, I have to say, with not a lot of reading matter around him.

Great Joss and His Playthings, a caricature near the end of his reign, sums up the worst of George IV’s proclivities.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

But there is another side of George IV, and this is his relation to Jane Austen. Austen’s entire adult life was spent while the Prince Regent—or, earlier, the Prince of Wales—was the leader of fashion. Her novels were all published during the Regency. She belongs to this era whether she likes it or not. And the consensus is that she probably didn’t like it at all.

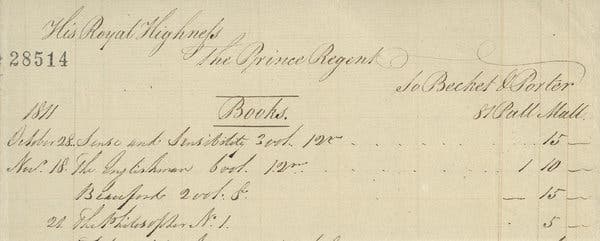

A timeline of this sort of half-relationship between Jane Austen and George IV begins with a discovery made as part of the Georgian Papers Programme, which intends to publish online the archived material from the Georgian period. This initiative of the royal collection is somewhat on hold now because of COVID, but I’m sure it will be renewed. One of the scholars on that project, Nicholas Foretek, discovered a payment, dated 28 October 1811, by the Prince Regent to Becket & Porter Booksellers for a copy of Sense and Sensibility, for fifteen shillings, or five shillings a volume. The Prince Regent had bought Jane Austen’s first novel before it had even been published.

A document in the Royal Archives memorializes the Prince Regent’s purchase of Sense and Sensibility for 15 shillings.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

The next stage in the process of any kind of interaction or awareness between the two comes with the sorry saga of the Prince of Wales’s marriage. In 1795 he married his first cousin, Princess Caroline of Brunswick. Both the princess and the couple’s child are commemorated in portraits. The first, on the left by Richard Cosway, a noted portrait artist, shows Princess Caroline several years later with her little baby daughter, Princess Charlotte (ca. 1797). The second, on the right, was done a few years after that by Sir Thomas Lawrence, another noted portraitist and the fourth president of the Royal Academy (1801). This portrait shows a slightly more grown-up princess.

|

|

| Portraits by Cosway and Lawrence show Princess Caroline with her daughter, Charlotte. (Click on each image to show a larger version.) |

|

By this time, the marriage had hit the rocks, and the issue became public a few years later, in 1806, when George, then Prince of Wales, commissioned a so-called “delicate investigation” into the conduct of his estranged wife. This investigation effectively cleared Princess Caroline of wrongdoing but permanently tarnished her reputation. The issue of the delicate investigation resurfaced in 1813 when the Princess of Wales wrote to her husband, who was by then Prince Regent, begging access to her daughter, complaining that though she had been cleared during the investigation, the calumnies still surrounded her.

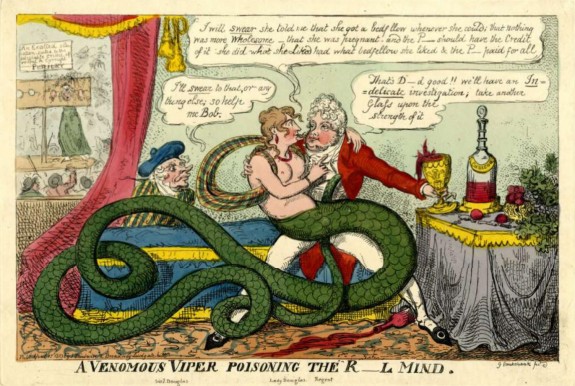

This issue again became public. Caroline crossed a line when she offered this letter for publication on 10 February 1813. Suddenly, the royal family’s dirty linen was being washed in public. This episode prompted a huge resurgence of interest, mostly on behalf of the princess. A typical caricature of the era targets Lady Douglas, the friend and companion of Princess Caroline, who had given evidence at the “delicate investigation.” One caricature (below) shows her as a giant serpent, with her hair cunningly suggesting a forked tongue. She sits on the lap of an absolutely delighted Prince Regent, saying, “Oh, I’ll swear to it if you like.” His response—“That’s great. Let’s have an ‘indelicate investigation’”—implies that George is going to investigate her. The artwork is very much against such traitorous friends and this scheming, malicious husband.

A caricature shows one of the Princess’s companions as a “venomous viper” conspiring with the Prince Regent.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

And this is the view, roughly speaking, that Jane Austen also took when she wrote on 16 February 1813 to her good friend Martha Lloyd. Austen writes about the episode in the following terms:

I suppose all the World is sitting in Judgement upon the Princess of Wales’s letter. Poor Woman. I shall support her as long as I can because she is a Woman and because I hate her Husband.

Nice and clear. She goes on to qualify that position slightly and concludes by saying,

[B]ut if I must give up the Princess, I am resolved at least always to think that she would have been respectable, if the Prince had behaved only tolerably by her at first.

Austen is clearly coming down on the side of the Prince of Wales, later George IV, as a kind of inveterate sinner, and Princess Caroline as somebody somehow caught up in that kind of activity.

The next episode in the story is not, we imagine, hugely welcome to Jane Austen herself. In 1814 the Prince Regent learned that Austen was in London and asked his librarian, James Stanier Clarke, to invite her to the library of Carlton House. Austen went, but she didn’t meet the prince. The librarian did tell her, however, that the Prince Regent would be very happy if Jane Austen’s next novel might be dedicated to him. That dedication duly took place. The novel in question was Emma. The dedication copy was sent before publication in December 1815. (Its official publication date was 1816.) This book is now in the Royal Library, a very important part of that collection. The dedication, set in large type so that it fills the entire page, reads as follows:

To His Royal Highness the Prince Regent, this work is, by His Royal Highness’s permission, most respectfully dedicated, by His Royal Highness’s dutiful and obedient humble servant, The Author. (3)

And you’re probably thinking, a little bit too many “Royal Highnesses,” but I can assure you: you can never have enough. That would have been absolutely what you’re required to do. But again, one can’t really imagine that Jane Austen’s heart was very much in it.

The next episode in this story was a letter from the librarian, Clarke, to Jane Austen in March 1816, in which he proposes to her that she write about the life of clergymen or “chuse to dedicate your Volumes to Prince Leopold: any Historical Romance illustrative of the History of the august house of Cobourg, would just now be very interesting” (Austen, Letters 27 March 1816).

Now this proposition isn’t altogether stupid. First, novels about the life of clergymen had worked before—The Vicar of Wakefield (1766)—and they will work again, in George Eliot’s Scenes of Clerical Life (1857) and Anthony Trollope’s Chronicles of Barsetshire, including The Warden (1855) and Barchester Towers (1857). So a clerical story is not a hopeless suggestion.

But more opportunistic was the idea that she might dedicate a novel to Leopold of Saxe-Coburg, who was the new prince on the scene. In March 1816, his engagement was officially declared to Princess Charlotte, the little girl in the previous portraits, now grown. The couple was married in May, which meant that if everything went to plan, the next dynasty of the British Royal Family would be of the House of Saxe-Coburg. It would be really quite sensible, in a way, to get some sort of romantic novel going about the daring deeds of some ancient member of the house, and it would all be nice and fresh and ready for publication soon after the marriage, fresh in everyone’s mind. And it would run and run throughout the next reign.

In a way, Jane Austen’s response acknowledges both the commercial and political opportunities while declining to take advantage of them. Her letter written to Clarke, the librarian, basically says, “Thank you very much,” and then expands:

You are very, very kind in your hints as to the sort of Composition which might recommend me at present, & I am fully sensible that an Historical Romance founded on the House of Saxe-Cobourg might be much more to the purpose of Profit or Popularity than such pictures of domestic Life in Country Villages as I deal in—but I could no more write a Romance than an Epic Poem.—I could not sit seriously down to write a serious Romance under any other motive than to save my Life, & if it were indispensable for me to keep it up & never relax into laughing at myself or other people, I am sure I would be hung before I had finished the first Chapter.—No—I must keep to my own style & go on in my own Way; And though I may never succeed again in that, I am convinced that I should totally fail in any other. (1 April 1816)

She would not follow, for example, Walter Scott, who was writing such romances at that date. He had just started the Waverley novels, and he was a friend of the Prince Regent. Her reply is a wonderful manifesto of Jane Austen’s novel-writing, sending all these other suggestions out of the window. In a sense, that’s the end of the story. Just to tie up some loose ends of the plot: Jane Austen died the next year, in July 1817, as, a few months later, did Charlotte and the baby that she was giving birth to. Had Austen started that novel on the Saxe-Cobourg dynasty, she would have had to shelve it, because it didn’t look very likely that they would be the next dynasty.

Meanwhile, the heir to the throne having died tragically in childbirth, all George’s brothers were trying to find German princesses in order to produce an heir. And duly an heir was produced, born in 1819 to the fourth son of George III, Edward, the Duke of Kent. By something of half coincidence, half manipulation of the ever manipulative Leopold of Saxe-Coburg, the wife that Edward selected was Leopold’s younger sister, Victoria of the House of Saxe-Coburg. These were the parents of Princess Victoria, later Queen Victoria, who again, through the machinations of her Uncle Leopold, married her first cousin, Albert of Saxe-Coburg.

So, had Jane Austen lived until that marriage, she would have had to have taken that history of the Saxe-Coburg dynasty off the shelf and started it over again. Because, indeed, the title of the dynasty was Saxe-Coburg as it turned out. But that’s long into the future.

![]()

What I want to do now is to ask the questions: Would not the future George IV have actually been more sympathetic to that manifesto of Jane Austen than we might think? How seriously did he take literature, and what were his attitudes to the world in general? These questions were broached very seriously at an exhibition, “George IV: Art & Spectacle,” recently held (15 November 2019–3 May 2020) at the Queen’s Gallery, which was curated by a team of us. The lead curators were Kathryn Jones and Kate Heard, and they were both particularly anxious to stress a rather more thoughtful and intellectual side to George IV than had previously been acknowledged.

This is absolutely not to say that he didn’t have the vices of thoughtlessness—of action, of behavior, of carelessness with money, and so on—but there was quite a lot of intellectual reflection which he was capable of. He might not have acted upon his reflections, but he was capable of thinking. And this thoughtfulness was particularly demonstrated in the exhibition, where the curators were able to show that his interests divided between a public spectacle side of his character and a private pleasure side. On both sides, there were thoughtlessness and chumpishness. But also on both sides, there was quite a lot of reflection. In the public realm, he was very interested in the history of the great monarchs or emperors that he might be imitating, those of Rome, or even the Pope, and of France, Louis XIV. He even had huge admiration for Napoleon, Emperor of France, his immediate rival.

On the private side, along with the mistresses and the gambling and the horse racing and the drinking and all the things that Regency bucks got up to, the curators were able to demonstrate that he had a really quite serious interest in the history of the theater, in literature, and in music. This is, of course, where the dedication of Jane Austen’s Emma particularly fits.

When we look at these two sides, we can see them reflected in portraits. A formal state portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence shows him standing proudly in the regalia of office, his crown on the table beside him. Another shows him sitting on a sofa in plain black clothing, a top hat and gloves next to him—a much more friendly, private, amiable, and affable image. It’s still powerful, but it provides a side that might relate to the people, which George IV definitely prided himself upon. However much they disapproved of him, everybody described him as engaging and charming when they met him. He had a very great skill of interaction.

| Portraits of George IV by Thomas Lawrence showing both his public side (right) and his more approachable private side (left) (Click on each image to see a larger version.) |

|

His public side can be seen in the transformation of Windsor Castle, which took place during his reign, on the exterior and on the interior. The renovated castle is now open to the public, so that you see the elaborate design and decorations. I recommend a visit, but I don’t think it’s something that Jane Austen would approve of. Her favorite painting of a monarch would more likely be of the king from her day, shown in James Pollard’s His Majesty George III Returning from Hunting. The image shows the polite, down-to-earth George III, who is coming from a hunt and stops to exchange greetings with a loyal subject. The nice, old, run-down, gothic Windsor Castle is in the background. Nobody is spending too much money; nobody is getting too above themselves. That’s the image that she would have liked.

Austen likely would have preferred the less ostentatious father of the Prince Regent, George III, shown here greeting a subject in this painting by Pollard.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

The other major building work by George IV brings us more to the pleasure and the culture side: his transformation of a house that had been called the Queen’s House and that came to be called Buckingham Palace. The architecture designed by John Nash reflects almost a dual purpose of this building. On the main facade, or the cour d’honneur (the “court of honor,” the main formal approach and forecourt of a large building), there is a very formal exterior with two secondary wings projecting forward on both sides. There was definitely a military triumphal side with a marble arch, which was subsequently moved. This front façade was where the throne room was, so this is where the public offices of the monarch would have taken place. It has subsequently been covered by Aston Webb’s façade of 1913. Much of the original idea you can see when you get inside the courtyard, but overall the effect has been lost.

But the garden facade remains from John Nash’s design. This is George IV’s façade. On the garden facade, he’s more concerned with cultivating the pleasures of life, particularly intellectual pleasures, serious pleasures. So, for example, in the prime location in the bay window in the center of the facade on the piano nobile (the main story of a large house, usually the first floor), we have the music room dedicated to that pleasure. Next door to it is an elaborate room dedicated, apparently, to literature or poetry. It has images of poets above the arches: Shakespeare, Spenser, and Milton. We can imagine the arts being celebrated here. You might say that a monarch has two fundamental roles, to rule and to encourage culture.

In the middle, the Nash design created a new space, which has no access to windows and therefore has to be top-lit, which is absolutely suitable, because this space is used as a picture gallery, which needs the light coming down from above. This picture gallery, which runs the entire length of the palace, is still there, though unfortunately the ceiling has been changed. There George IV hung a collection of paintings that he had formed in the previous years and that had previously been hung or housed at Carlton House. Another pleasure, the pleasure of art, is being celebrated in the heart of the palace.

The question now that I wish to address is, what sort of art did George IV hang in this space? The short answer is that he hung Dutch and Flemish paintings. At the time, those words, Dutch and Flemish, were used quite interchangeably. It’s confusing, because today we distinguish between the two. We might call them Netherlandish or perhaps painting of the Low Countries, but these would be paintings from the Dutch republic or the Spanish Netherlands, the vast majority of them created during the Golden Age of the seventeenth century. This is what is he hung in the gallery.

One example is Rembrandt’s Shipbuilder and His Wife, for which Prince George paid the astonishing sum of 2,500 guineas. I begin with this painting because it’s a very striking statement of preference by the monarch. Not that Rembrandt hadn’t been a much-admired artist for at least the previous century, but the idea of hanging in a prominent place a painting of a merchant in a royal palace is very, very surprising. In addition, in this selection I think you have a very clear indication of George IV’s enthusiasm for the physical experience of paint. He liked paintings that were really sensually painted, and he liked them to be in very, very good condition. (They still are in very good condition.) Suddenly, painting is not just about ideas: it’s about the sensual experience, the tactile experience of looking and imagining that you’re feeling the surface of the painting. This is a particularly striking example.

Rembrandt’s Shipbuilder and His Wife received a place of honor in George IV’s collections.

This brings us back to Carlton House. The Shipbuilder and His Wife was brought over from there, and it had hung very prominently there on the garden façade on the first floor in the Blue Velvet Room. Carlton House had a very, very similar contrast between rather a martial, severe, forbidding public cour d’honneur, the main formal approach along Pall Mall, and then this very domestic, almost understated garden façade opening onto the garden. It was along the garden façade where the highlights of the collection were hung. It is astonishing that a Rembrandt had made it to such an exalted setting at Carlton House as well as at Buckingham Palace, and even more so if you look at the painting which works, really, as its pair. There are four paintings of note, two pairs of two paintings each. The first painting is a Van Dyck religious subject, Christ Healing the Paralytic. Van Dyck had always been considered a very high-status artist, because of his having worked for Charles I, but also because he worked in an Italian idealized style, and this is a religious painting. To have this paired with a Rembrandt depiction of a mere shipbuilder was a very striking mismatch, almost, but a mismatch that elevates the status of Rembrandt.

Van Dyck’s Christ Healing the Paralytic, considered high art, was paired with the “ordinary” Rembrandt in the Blue Velvet Room along the garden façade.

The Blue Velvet Room

(Click here to see a larger version.)

So we’re already moving in a particular direction in reading the taste of George IV, of the ordinary as well as the elevated. This is a different direction from what one might have expected, especially if we examine and compare what he grew up with. Here he is at Buckingham House as a child in a Johann Zoffany painting of 1765. We see him in front with his brother Frederick, with the paintings on the walls having been hung by Queen Charlotte. There we have Van Dyck royal portraits very prominently, very appropriately displayed, and we’re having a “rhyme” between the little royals in front and the paintings on the walls of the royals from way back. Zoffany creates a relationship between them.

Zoffany’s portrait creates a visual “rhyme” between generations of royals and ties them to elevated Italian sensibility.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

On the wall behind we also have an Italian, seventeenth-century Baroque painting, which would have been regarded as the highest status of painting for that date. We understand the importance of the Italian art if we evaluate what this room actually looked like at the time. (Often, they would arrange backgrounds differently for the purposes of portraits.) The room was dominated by two Italian Baroque paintings, one by Carlo Maratta and one by Guido Cagnacci. These two paintings exactly expressed the ideal of art that was current at the time and that formed the theory of the foundation of the Royal Academy in 1768, as well as the substances of the discourses delivered by Sir Joshua Reynolds at the Academy from that year onwards. If you asked what Reynolds, the first president of the Royal Academy, would be recommending as a model of art, the answer would be something like Guido Reni’s Cleopatra, which was acquired by Frederick, Prince of Wales, George IV’s grandfather. Cleopatra was hanging in Buckingham House when George IV grew up. It’s a very, very high-status painting. Reni was often referred to as the “Divine Guido.” The pale Cleopatra, looking heavenward, is being bitten by the asp and is soon to die. This is what painting is supposed to look like.

Cleopatra shows the etiolated Italian style.

And before I explore why, it’s worth pointing out that there were some dissenting voices. If we go back to the date that Frederick acquired this painting in the 1740s, we find somebody who wasn’t committed to this style: William Hogarth, the great satirist, for whom this type of Italian painting is just another example of poor aristocratic taste. Hogarth’s Marriage à-la-Mode, Scene IV (1745) presents an interior scene. The walls in the background are covered in these kind of Italian daubs, typical Italian paintings showing gods or heroes and featuring a lot of nudity. In Hogarth’s mind, the scenes are either brutal or obscene, but definitely bad for the morals. And, I think, in his view, they would be thoughtless and vacuous in their subject matter and maybe a little bit empty and vaporous in the way that they were painted.

In Hogarth’s mind, they’re connected with debauched behavior. In his satiric painting, the ten characters in the room are partying. The countess shown is up to no good. Another woman is very affected. On the right side is a castrato warbling away. The love of Italian opera is very suspicious in his view. We have an overlap here, perhaps, with Jane Austen’s view as expressed through Anne Elliot in Persuasion when she’s discussing the text of an Italian opera aria that she translates for her neighbor. Anne says: “‘This . . . is nearly the sense, or rather the meaning of the words, for certainly the sense of an Italian love-song must not be talked of’” (186). Don’t expect an Italian song to mean anything: it’s nonsense. That sort of view might be shared about Guido Reni’s Cleopatra. Is that really what it looks like to die of a snake bite? Probably not.

We can see this contrast with the Italian school in another painting by Hogarth, David Garrick and His Wife, Eva-Marie Veigel. It’s an interesting example. It was painted in 1763 and acquired by George IV in 1826 for 150 guineas. Why did he buy an out-of-date painting? He clearly was very interested in it. The painting depicts a celebrity media couple, David Garrick, the great actor, and his wife, dancer Eva-Maria Veigel. In Hogarth’s mind, this is the exact opposite of everything represented in Marriage a la Mode. This is a happy, not an unhappy, marriage. These are down-to-earth, good-humored, fun-loving—rather than affected—people. The difference also involves the way that it’s painted. Rather than the vaporous, slightly etiolated Italian way of painting, like Reni’s, the Hogarth has a kind of chunky, physical, sensual realism. It’s a down-to-earth English kind of painting. It’s vivid and bright and cheerful, and it may be inspired by Rembrandt. It’s a bit lighter than Rembrandt, but it’s got that physical energy almost of Rembrandt’s work, and it values the same kind of realism. In a sense, you’ve got in one painting all Hogarth’s ideas about what’s wrong with elaborate Baroque painting.

But perhaps we should also ask what was right about it. Why did people value the elaborate Italian style of painting? And why did they set this value up against Dutch painting? They set up a duality between Italian painting and Dutch painting that, I’m seeking to argue, is not a good/bad duality but a “good for one sort of situation, good for another situation” of duality. This I think we would see particularly in Sir Joshua Reynolds, who would recommend Guido Reni’s painting of Cleopatra but would perfectly well enjoy and admire a painting by Jan Steen, Girl at Her Toilet, showing an ordinary female getting dressed for the day.

But what are the ideas that would be flying around about Reni’s painting versus Steen’s? I think there are three. Everybody would agree that both these paintings are concerned with realism. But the first idea is that the Guido Reni is concerned with an ideal form of reality, which is superior to, which is more beautiful than the reality of the world, whereas Jan Steen is simply interested in reality and, therefore, perhaps has to go a little bit further in recreating that reality. The actual grittiness of the realism is more important in Dutch art because it’s all you’ve got. The two contrast the ideal versus the real.

The second element would concern drawing, which was regarded as the kind of intellectual, elevated part of art as opposed to using the brush, as opposed to coloring, as opposed to painting. The Guido Reni would be thought to have had that learned, serious quality in draftsmanship. It resembles a piece of sculpture, whereas the Jan Steen would be seen as purely a brilliant display of coloring without the solid intellectual background of drawing.

The third idea would be a contrast between the Guido Reni, which is a tragic scene, the most elevated form of drama, and the comic Jan Steen scene, a less elevated form of drama. I would argue that there was an absolute broad acceptance of this contrast. And though you do find many people apparently casually attacking Dutch painting throughout this period and throughout the subsequent century, they can’t all have attacked it because, otherwise, why did they have so much of it, like it so much? Why did they spend so much money on it? The one thing that’s absolutely certain is that this type of middle-life—low-life or bourgeois Dutch painting—was extremely fashionable throughout Europe, particularly in France and in Britain. A painting by Henri-Pierre Danloux, The Baron De Besenval (1791), captures the dichotomy. The painting shows the baron in his study, a very aristocratic collector in a grand French interior with his walls absolutely covered in small-scale, low-life Dutch painting. It’s this sort of taste that George IV bought into.

He didn’t invent it. George IV was not a trailblazer. He was very happy to follow fashion—interesting, because he does so much to sum up fashion. George IV does pretty much the same as that aristocratic French collector in Danloux’s painting. Carlton House, which has the severe façade in front, and the nice garden façade in the Bow Room, also has a central, grand space in the Rose Satin Room that was absolutely filled with Dutch and Flemish scenes of low life. They’re arranged in groups of “one over three” all around; each section of wall has them. Often, there are complementary groups opposite each other, each a large painting over three small paintings. Beautifully arranged, beautiful symmetry.

| Rose Satin Room at Carlton House was jammed with scenes of “low life” from the Low Countries, often with one large painting above three small ones. (Click on each image too show a larger version.) |

|

I suggest that the admiration for this kind of art among collectors, George IV and others, was not just based on an admiration for the painterly qualities, though that was important, too, the brilliant handling of the brush, the realism. But there were broad categories of subject matter which the collectors felt absolutely at home with and which they would have broadly identified through a knowledge of literature, a knowledge that they would have had far more profoundly through their intellectual upbringing than a knowledge of painting. Absolutely everybody was brought up with literature.

We can group them according to subject genres. And at the same time, also, this selection will show you the names of the blue-chip artists who were being collected at this time. There is quite a small number, about fifteen or so, that crop up all the time. David Teniers the Younger was number one, at the very top of the list.

Of the genres, the first one is the idea of the cavalier: a gentleman who, usually but not necessarily, is riding a horse, who is engaged in a manly or venturesome activity, either as a soldier, as an officer, or as a huntsman. He goes out into the world and encounters rustic, low-life people and odd sorts of scenery. It’s the adventure of a nobleman, framed through the eyes of a nobleman. Two examples come from a favored artist at this date, Philips Wouwerman, whose themes were usually hunting, landscapes, and battles. In one, called The Hayfield, we see an ordinary, rustic harvest scene, but it is viewed through the eyes of two hunters who have been hawking, two cavaliers experiencing this scene. The second example shows a cavalier drinking at an inn. It’s a bit of a squalid inn, but the hunter is quite stylish, as is his mistress. Again, we are seeing the scene through the eyes of the huntsman. There must be a literary equivalent in the eighteenth century, but the only one I can think of is Turgenev’s A Sportsman’s Sketches (1852). Marvelous work, but obviously a little bit too late historically for our purposes.

Another example of the high life contrasting to the low life in natural scenes was also a pair that hung opposite each other; they have similar dimensions. These two give us a “before and after.” One, the Hawking Party, is a very grand party just setting out. The other, Sportsmen at An Inn, shows a couple of huntsmen who have been shooting. They arrive at this incredibly squalid, run-down inn and try to get themselves something to eat and something to drink. It’s a comedy of collision between the expectations of these grand people and the ability of the simple innkeeper to meet those expectations. Both artists, Adriaen van der Velde and Paulus Potter, are very, very popular at the time.

The second category, super familiar from any literary point of view, is the pastoral, which in Dutch art means Italianate scenes of peasant life, of shepherds and shepherdesses. Often the scenes are not particularly idealized, but they invariably exhibit one or two beautiful figures. A shepherdess will be perfectly beautiful, even if the surroundings are a bit ordinary. You couldn’t imagine anything more graceful than the female figure in Shepherdess with Kid, even if everything else is a bit low life. That mixture of a kind of grace with something pretty rustic is totally common from the literary genre of the pastoral. There’s always a Touchstone and an Audrey—Touchstone from the court, Audrey from the country in Shakespeare’s As You Like It—as well as the high-quality Rosalind. The French or English aristocrats seeing this art are going to be totally at home here. They know exactly where they are. Artists, again, pretty familiar, are Adriaen van der Velde and Nicolaes Berchem, a big figure in the inner circle of this canon of Dutch art that is very light.

The next category, probably a bigger one altogether, is the local peasant comedy. Again, these are scenes very familiar from literature. These are the people that Shakespeare would have called “hempen homespuns,” as in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. But there are also peasant characters in Molière. We think Molière is a bit more bourgeois, but there are peasant characters in Molière. So the idea of a broad, rustic comedy is pretty widely dispersed throughout Europe.

It is also extremely easy to read these paintings. Teniers, already mentioned, would absolutely be one of the commonest artists in these princely cabinets, along with Adriaen van Ostade’s work. Teniers excels in comic versions of peasants behaving badly. In Peasants Dancing, they’re throwing up because they’ve drunk too much. They’re getting a bit lustful. They’re making a spectacle of themselves dancing in a rather overenthusiastic fashion. But they also have a little gallantry. There’s a certain amount of rustic charm. One peasant is asking a bourgeois girl to dance because in this time there were prosperous city dwellers going for walks to the town of Kermis. This strange mix is almost like a spectacle, and it is very easy to see the comedy.

But, also, there’s definitely a political side because this idea of the rustic dance, whether it’s a harvest festival or Kermis, was definitely associated with the idea of a prosperous and happy state ruled over by a good king. We see this circumstance again at Carlton House, a painting of a sort of informal throne in the so-called Colonnade Room in which Prince George is shown in a painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence. The background is a bit idealized, but the table and sofa are that same table and that same sofa from Lawrence’s earlier portrait.

Kermis on St. George's Day

Harvest Feast with Drij Toren

Hanging next to him on the walls on either side of the fireplace were two David Teniers, which were made into a matching pair because they’re about the same size. Both Kermis on St. George’s Day and Harvest Feast with Drij Toren show peasant scenes and festivals. In 1795 there was even a “Dutch fête,” which was laid on at Frogmore House, near Windsor Castle. Frogmore House is within the grounds now, though it wasn’t then. The fête was held in the presence of the Prince of Wales, the future George IV, and the Prince of Orange, obviously from the Netherlands. Imagine it as a stage set serving as a model in which the kings of Arcadia are celebrating and happy chaps are dancing all around.

The next and final category of a literary category into which the art of seventeenth-century Holland fits is the bourgeois comedy. We can see it in a painting by Gerrit Dou, one of the biggest names in the inner canon. We know of his place because Prince George bought this painting at 1,200 guineas, which per square inch is quite a high value. It’s only 49 by 38 centimeters (19 by 15 inches). Some of the paintings are very, very small, featuring highly detailed, jewel-like, brilliant illusionism—fabulous depictions of light. But they also present scenes of bourgeois prosperity that are familiar to everybody through bourgeois comedies that date from antiquity. These were the heart of Molière, who I think of as the most easily identifiable purveyor of classical comedy into the early modern world and a playwright admired and imitated throughout Europe. He sums the whole thing up.

And what I want to discuss now is the way in which a Dutch painting is, as it were, Molièreized. It’s the sort of material made into a Molière play. You can see this in Godfried Schalcken, a pupil of Gerrit Dou. He painted The Family Concert, which the Prince of Wales acquired in 1810. I’m sure that one of the reasons he acquired it was that it was already famous: the image had been disseminated through a print by Wille in 1769. In addition to the image, the print has the coat of arms of the owner and also a grand title. Paintings at this time didn’t have titles unless they appeared as a print—when they then acquired one. This one, then, became Le Concert de Famille. It’s almost as if the painting has become a publication, almost become a Molière play. That would stimulate a particular way of reading these paintings so that you’re invited to “read a plot,” to read interactions between characters.

I want to finish by speaking about English or British art inspired by these Dutch examples, in which we see examples that are elevated by association with seventeenth-century Dutch painting. For example, in the Blue Velvet Closet at Carlton House, you have these two framing paintings, almost symmetrical, by Gabriel Metsu and Nicolaes Maes. Both have very easily readable subjects. On the left, the woman is going to catch these misbehaving servants out. On the right, two lovesick men serenade a woman. These paintings hang on either side of another painting by William Hogarth acquired by the Prince of Wales showing his grandfather Frederick, who had also lived at Carlton House, rubbing shoulders with all and sundry in St. James’s Park over the back garden fence. Again, it brings the idea of an open-hearted king who embraces all his people, and George would enjoy that kind of painting. Hogarth represented that good old spirit of English liberty.

Domestic scenes by Maes and Metsu framed a Hogarth painting that celebrates open-hearted royalty embracing the public.

(Click on each image to see a larger version.)

At the end of the prince’s collecting of Dutch art, he takes it up a notch when he starts discovering artists like Pieter de Hooch. A dealer at the time wrote that de Hooch was providing something completely new in everybody’s understanding of Dutch art. In 1810, he writes that connoisseurs had opened their eyes to de Hooch’s merit. He describes a room “brilliantly lighted from a window in front with a courtyard beyond. The effect produced is perfectly illusive”—its illusion is perfect. “And for the management of its light and shadow, this is the most surprising picture I’ve seen by this painter.” He says that there is a level of perfect illusion superior to anything anybody had seen. Whereas traditional realistic paintings have more of the verisimilitude of a stage than that of the actual world—the characters are all arranged for our benefit—the de Hooch is real. It’s not on a stage. It’s as if we’ve really stumbled into a real scene. It’s another level of recognition of the world as it actually is, in addition to this extraordinarily effective light. In this painting and in the other de Hooch acquired by George IV, there is a parallel with Jane Austen, evident in Walter Scott’s review of Emma, published in March 1816. Scott says that Austen’s novels “belong to a class of fictions which has arisen almost in our own times, and which draws the characters and incidents introduced more immediately from the current of ordinary life than was permitted by the former rules of the novel” (59). He elaborates:

Emma has even less story than either of the preceding novels [Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice]. . . . The author’s knowledge of the world, and the peculiar tact with which she presents characters that the reader cannot fail to recognize reminds us something of the merits of the Flemish school of painting. The subjects are not often elegant, and certainly never grand; but they are finished up to nature, and with a precision which delights the reader. (65, 67)

Exactly those words could be said about a Dutch picture: that it is finished up to nature—getting the bright, gleamy finish and that precision as well as the truth about something completely ordinary. Nothing is happening, a comment often applied to Austen’s stories. Courtyard in Delft, for instance, is just a glimpse of a courtyard, cheating your expectation of a theatrical kind of event being presented to you.

It might be something that Emma sees when she looks out of the window at Ford’s shop, where she observes only ordinary people going about their ordinary days but recognizes that “she had no reason to complain, and was amused enough; quite enough still to stand at the door.” In addition to his vices, and to his enjoyment of public grandeur, Austen’s royal fan also has a “mind lively” that “can do with seeing nothing, and can see nothing that does not answer” (E 233).

As in Austen’s novels, “nothing is happening” in the Courtyard in Delft . . . except life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The editor thanks Collins Hemingway for transforming the transcript of Mr. Shawe-Taylor’s talk into essay form.