What great house was Jane Austen thinking of when she made Pemberley a residence in Derbyshire to be admired and visited by Elizabeth Bennet in the first chapter of volume 3 of Pride and Prejudice? Jane Austen directs the reader to follow her progress through the grounds, to witness her developing admiration of the house’s situation and the appearance of the building itself, and then to accompany her inside. It is not surprising, then, that readers have wondered what the real inspiration for Pemberley was. Among them is Pat Rogers, the editor of the novel in the authoritative Cambridge Edition of the Works of Jane Austen (2005) who argues in appendix 3, “Pemberley and its models,” that “Jane Austen probably had aspects of Chatsworth in mind when describing Pemberley, though the house is not modelled in every detail on the real-life estate, and is imagined to exist on a far less palatial scale” (452).

Coincidentally in the same year, the association of Pemberley with Chatsworth was augmented by the use of many features of the mansion in the film of Pride & Prejudice directed by Joe Wright and starring Keira Knightley. Rogers points out that the party in Pride and Prejudice “crosses the river . . . by means of ‘a simple bridge’, which suggests something a little less imposing than the three-arch bridge over the Derwent near the house at Chatsworth” (453). In the movie this imposing bridge features in an important moment when Knightley as Elizabeth surveys the building and grounds from its distance and is apparently overcome by the scene’s magnificence. Elizabeth is also seen descending a glamorous staircase, and (in a sequence beautifully shot) wandering through its famous sculpture gallery. Such scenes must have confirmed many people, whether readers of Jane Austen or not, in the conviction that Pemberley is a palace.

This association of Pemberley with Chatsworth is untenable for many reasons, as I will argue, and belongs to the realm of myths around Jane Austen and her novels that Claudia L. Johnson and Clara Tuite have recently explored in 30 Great Myths About Jane Austen (2020). Chatsworth, though certainly one of “the celebrated beauties” of Derbyshire mentioned earlier in Pride and Prejudice (265), cannot be considered in any way as Jane Austen’s model for the fictional Mr. Darcy’s estate of Pemberley, so I explore other possibilities, while addressing the question of what light might be thrown on Austen’s authorial imagination by the pursuit of this enquiry.

In 1813, the year of Pride and Prejudice’s first publication, however, Chatsworth was not so large as it is now. The sixth Duke of Devonshire had succeeded his father in 1811, and he soon determined on a radical and ambitious scheme “to provide an entirely new set of magnificent entertaining rooms” as well as, among other additions, a library, the sculpture gallery, a conservatory, and a theatre. This lavish new North Wing, which doubled the size of the house, was not completed for over twenty years. As John Martin Robinson writes in The Regency Country House, “It was the most expensive private house project of the age” (62).1 Olive Cook in The English Country House comments on the extravagance and “exuberance” of the elaborate waterworks around the house and especially on “the Cascade and the Long Canal. The latter is higher than the ground on the south side of the house, so that the silvery building appears from a distance to float on the shining water” (134). Always thought a great and magnificent building, recognized by art historians and visitors as a “princely residence,” the Duke’s love of splendor resulted also, for example, in ceilings painted by Laguerre, which are unfortunately reminiscent of Alexander Pope’s lines in his Epistle to Burlington deriding over-expensive houses: “On painted Cielings you devoutly stare / Where sprawl the Saints of Verrio or Laguerre” (Moral Essay IV, ll. l44–45). In comparison, “The rooms [of Pemberley] were lofty and handsome, and their furniture suitable to the fortune of their proprietor,” Jane Austen writes, adding “but Elizabeth saw, with admiration of his taste, that it was neither gaudy nor uselessly fine” (272).

But there are stronger reasons than divergent stylistic taste to dismiss Chatsworth as a model for Pemberley. It was also the home of the Cavendish family, lately become the Dukes of Devonshire. Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, “a celebrated beauty and social figure” as Rogers rightly calls her (452), was a friend of Sheridan and an ardent campaigner for the opposition Whig party led by Charles James Fox. During the period of George III’s so-called “madness,” from 1788 to early 1789, Fox worked closely with the Prince of Wales, who was scheming to take over his father’s throne. From her base in Derbyshire, the Duchess, an astute and persevering politician, sent many letters to her metropolitan colleagues advising on tactics and receiving back, no doubt gleefully, any news of the king’s declining condition (Sichel 2:213–31).

Chatsworth’s manifestly Whig associations would be enough to discredit any connection of Pemberley with this palace. Another important “stately home” in Derbyshire is Haddon Hall, close to Bakewell, then a small town and often thought to be the model for Lambton, “the little town” with the inn where Elizabeth and the Gardiners stay in Pride and Prejudice. Haddon is a medieval castle with a long and wide gallery, but it does not house the family portraits. To find a possible match for the portrait gallery that is so important in Pride and Prejudice one needs to go to another Derbyshire house, Sudbury Hall, in the south of the county (hence it was utilized in the 2005 film). Picture galleries featuring ancestral portraits are in any case common—famously, for example, the source of much comedy in act 5 of Sheridan’s The School for Scandal.

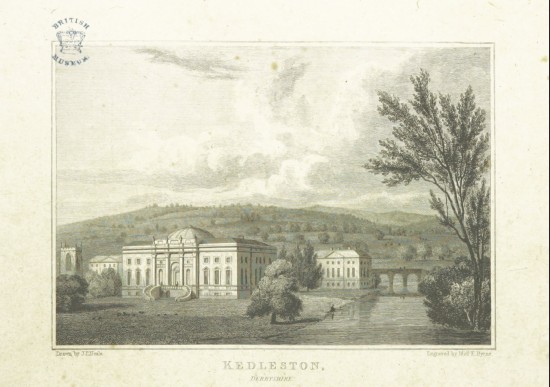

A much more plausible candidate for Pemberley is Kedleston Hall, another Derbyshire house, though in the south of the shire, unlike Chatsworth and apparently Pemberley, which are both in the north. Kedleston is certainly grand, but not quite so huge nor certainly so famous as Chatsworth. Like Chatsworth it has large grounds. The home of the Curzon family, who hired Robert Adam, the fashionable architect of the Regency period, to design it in classical style, it was apparently built to rival Chatsworth. More importantly, Kedleston was a political base of the ruling Tory party, led by William Pitt the Younger. The Tories strongly maintained the legitimacy of the established Church of England against the Whigs and would therefore almost certainly be supported by the Reverend Austen, Jane’s father. (Perhaps though, some clergy might be suspicious of the Tories, on the ground of their possible association with the Jacobites). Little is known for certain about Jane Austen’s own politics, but it may be worth recalling that in a letter of 16 February 1813 she said, with good reason, that she “hate[d]” the Prince Regent, even though she was later cornered into dedicating Emma to him.

Kedleston, Derbyshire (1818) by John Preston Neale

Kedleston was visited by Samuel Johnson and James Boswell in September 1777. They were staying with Johnson’s friend Dr. Taylor, who lived about eight miles away in Ashbourne. Boswell was “struck with the magnificence of the building” and in his Life of Johnson gives a rhapsodic account of “the extensive park, with the finest verdure, covered with deer, and cattle and sheep” as well as “the number of old oaks,” which filled him with “a sort of respectful admiration” (3:160). He also admired “the large piece of water formed . . . from some small brooks.” Most interestingly, he writes, “Our names were sent up, and a well-drest elderly housekeeper, a most distinct articulator, shewed us the house” (161). Boswell’s Life was published in 1785, and it would certainly have been purchased by Jane’s father. Her admiration of “dear Dr. Johnson” is well known. (Interestingly, it was a few days later on this trip that Johnson dictated his compelling “Argument” against the slave trade.) This Johnsonian connection would be enough to suggest that Kedleston was in Jane Austen’s mind—even though “magnificence” is not a term that suits Pemberley.

The housekeeper who similarly guides Elizabeth and the Gardiners through the rooms of Pemberley is called Mrs Reynolds. She too is a “most distinct articulator” in the sense that she conveys a good deal of information about the house and the family who owns it—information vital to the novel’s plot. Her commendation of Mr. Darcy fills Elizabeth’s thoughts in the famous moment when she stands in front of his portrait. “What praise is more valuable than the praise of an intelligent servant?” she thinks (277), her author here evidently echoing Johnson’s conclusion in issue 68 of the Rambler: “The highest panegyrick, therefore, that private virtue can receive is the praise of servants” (361). The name “Reynolds,” as Rogers points out, is significant, but it seems farfetched to link it with that artist’s portrait of Georgiana, and thence with Chatsworth. It is more likely to be a hint at a Johnsonian connection. Sir Joshua Reynolds was Johnson’s best friend, completing four portraits of him, each depicting a different aspect of the man and all equally compelling (see Vuillerman). Visitors to Kedleston today are still greeted by a woman dressed as the housekeeper who welcomed visitors like Johnson and Boswell.

But Kedleston will not pass muster, either, as the model for Pemberley. Though not quite as famous as Chatsworth, it is as grand in its own way. Entering the house, a visitor, like Johnson and Boswell, is confronted with a huge marble hall designed to suggest the open courtyard of a Roman villa. The floor is of marble, and a dramatic phalanx of twenty alabaster columns with Corinthian capitals leads the eye through the huge space. It is almost overwhelming. The underwhelmed Johnson had earlier countered Boswell’s raptures over the grounds with “Nay, Sir, all this excludes but one evil—poverty” (160).

The Marble Hall at Kedleston

One might ask then whether it matters what was the model or prototype of Pemberley. All we need to suppose is that Jane Austen knew that north Derbyshire (today the “Peak District” and the first area to be named a National Park in England) was a favorite tourist destination, that there were a number of “great houses” to be seen there (including one I have not mentioned, the Elizabethan “prodigy house” Hardwick Hall), and that suitably genteel visitors were usually shown round by a housekeeper. Perhaps Jane Austen had nowhere in particular in mind—though she does specify its location and supply enough information about the house’s setting and grounds to tease a reader’s curiosity.

In this chapter, Jane Austen leads her readers very assiduously step by step through the park that surrounds the house, taking them gradually on a journey that leads them to

Pemberley House, situated on the opposite side of a valley, into which the road with some abruptness wound. It was a large, handsome, stone building, standing well on rising ground, and backed by a ridge of high woody hills;—and in front, a stream of some natural importance was swelled into greater, but without any artificial appearance. It banks were neither formal, nor falsely adorned. (271)

The effect is to make us believe, or half-believe, as we follow her journey, that the house really exists and, as we read, to share Elizabeth’s developing admiration of its setting and then of the house itself. There is quite enough specificity (the stream having been “swelled into greater,” for instance, hints at the work of a landscape gardener like Repton) to induce a reader into the momentary belief that this is a “real” place. If we seek possible models or inspiration for Pemberley outside Derbyshire, there are of course many in England, including Godmersham Park in Kent, which, inherited by Jane Austen’s brother Edward and often visited by his sister, is an obvious alternative candidate. An eighteenth-century house, it is, like Pemberley, “backed by a ridge of high woody hills” but is without the stream that is featured in front of that house.

What does this collocation of great houses suggest? That none of them was Jane Austen’s “model”? What then can we learn from this survey about Jane Austen’s habits of thought, as present in her writing? I suggest that to nominate one specific place, or even several, as her inspiration is to misunderstand the nature of her imagination. Perhaps it is helpful to recall Elizabeth Jenkins’s vigorous condemnation in her 1938 biography of “the folly and the uselessness of attempting to establish definite connections between the world she lived in and the world of her imagination” (62). This is a view that runs broadly counter to the contemporary ethos of new historicism, which seeks to throw light on a writer’s work precisely by relating it to historical facts or circumstances that surround, and may be shown to influence, certain aspects of the text. In this essay I have invoked such surroundings but kept clear of any definite “connections.” One can only conclude that if Pemberley is a “real” place, this is because it was so vividly realized in Jane Austen’s imagination. And because she describes Elizabeth’s approach to the house and the house itself so persuasively and attaches a reader’s interest so closely, it then becomes real in our own.

NOTES

1Robinson’s book treats Chatsworth in the section on “Palaces,” providing twelve beautifully illustrated pages on the building’s splendors.