Carriages, we are told, bring young, eligible men into the neighborhood. Just a few sentences after the iconic opening of Pride and Prejudice—“It is a truth universally acknowledged . . .”— Mrs. Bennet announces that just such a wealthy young man has entered their neighborhood, her evidence being his arrival “‘in a chaise and four’” (1). This pronouncement provides us with an important clue to all of Jane Austen’s novels: Horse-drawn vehicles play a necessary role in the development and understanding of her characters and the plots of her novels. In a world of democratized ownership of automobiles, modern readers have little to no frame of reference for the economics, customs and social conventions, and operation of horse-drawn vehicles in her novels.1 Austen uses carriages to establish the measure of a person’s wealth and social distinction, to embody the perfect wedding accessory, to offer an analgesic for boredom, to express feelings, to provide a means of control or freedom, and to suggest the quality of a person’s nature.

Barouche Taste on a Buggy Budget

Austen establishes wealth based upon both the type of carriage and how many horses pull it—Mr. Bingley’s chaise and four being a prime example. Owning more than one carriage, like Augusta Elton’s brother-in-law, Mr. Suckling, shows that he has a considerable amount of “disposable income” (Jones 19; E 183). Marianne Dashwood believes a “‘competence’” of £1,800−2,000 a year to be the minimum income needed to maintain a household “‘of servants, a carriage, perhaps two, and hunters’” (SS 91).2 According to Hazel Jones, “[a]n annual income of £1,000 was the generally agreed requirement for living comfortably and maintaining an equipage with the animals to power it, together with the necessary stabling, coach house and servants” (19). In addition to these costs, there were luxury taxes on carriages, which increased based upon the number of vehicles owned (Jones 80).

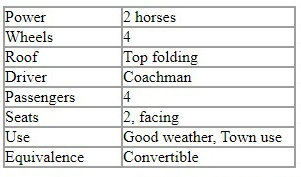

According to this scale, Lady Catherine de Bourgh was extremely wealthy. If there were doubts of her wealth, given Mr. Collins’s effusive descriptions of Rosings and its £800 chimney-piece, they are dispelled by his mention of “‘her ladyship’s carriages, for she has several’” (PP 157). It is unclear just how many carriages she owns: we can count her daughter’s low phaeton, the barouche Lady Catherine uses to travel to London, and the vehicle that conveys the Collinses and their visitors back to the rectory. Lady Catherine herself also uses vehicles as a measure of wealth; in her interrogation of Elizabeth Bennet about her family, one of the questions is about “what carriage her father kept” (164).

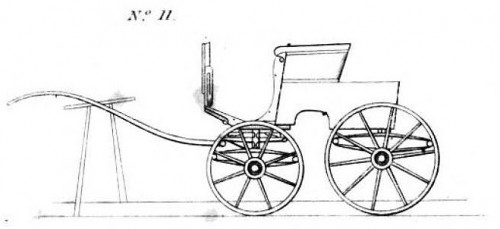

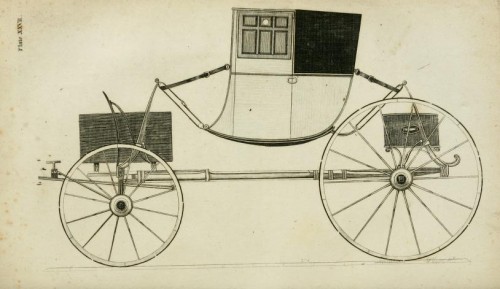

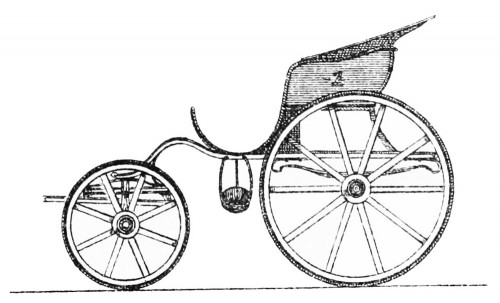

Little or low phaeton. T. Fuller, An Essay on Wheeled Carriages (1828)

Principal owners: Miss de Bourgh (PP) and Elizabeth Darcy via Aunt Gardiner’s wish (PP).

William Felton in A Treatise on Carriages describes the phaeton as “the most pleasant sort of carriage in use, as they contribute, more than any other to health, amusement, and fashion . . . and are proportioned to the sizes of the horses” drawing them (2: 68). If ponies are used, it is a lightweight, low, and steady vehicle that can be driven by a woman.

Likewise, General Tilney treats Catherine Morland to the most ostentatious display of carriage travel described in Austen’s novels. The Tilney’s journey from Bath to Northanger Abbey includes Henry’s curricle, the chaise and four, and many outriders. Though Catherine initially admires “the style in which they travelled, of the fashionable chaise-and-four—postilions handsomely liveried, rising so regularly in their stirrups, and numerous out-riders properly mounted,” the General’s behavior during the necessary two-hour wait at Petty France to rest the horses dims this view (NA 156).

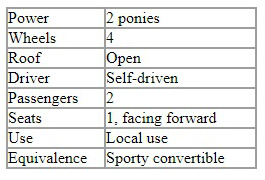

Chaise. W. Felton, A Treatise on Carriages, vol. 2 (1796)

Principal owners: Mr. Bingley (PP), the Hursts (PP), Colonel Brandon (SS), the Bertrams (MP), Mr. Rushworth (MP), the Sucklings (E), General Tilney (NA), and the Elliots (P).

Olsen describes the chaise as a “four-wheeled carriage that could be thought of as a half-coach.” It is “identical to a chariot,” but without the box for the driver; instead, the driver or two postillions (depending on whether there are two or four horses) ride on the horses (Olsen 1: 135). The chaise’s advantage over the additional baggage and people carried by the coach is its speed; Olsen concludes that “the chaise was a practical, yet not stodgy, vehicle” (1: 136). Felton waxes eloquent about the chaise: “A post-chaise is a carriage intended only for expeditious traveling, and, for a close carriage is the most pleasant; the view in front not being obstructed by a coach-box, nor the draught impeded by any cumbersome weight: lightness and simplicity are the principles on which this carriage ought to be built, if intended for post work only” (2: 50). Felton encourages those who often travel and can afford it, to purchase their own chaise, to spare themselves the inconvenience of frequently changing carriages and transferring luggage from one vehicle to the next (2: 51).

Ownership of a carriage was not only a proof wealth but also an indication of social standing. Fanny Dashwood and her mother, Mrs. Ferrars, understand the status a certain type vehicle bestows upon a person. They want Edward to make something of himself—in politics, the army, law, or the navy—but until he does, “it would have quieted [his sister’s] ambition to see him driving a barouche. But Edward had no turn for great men or barouches” (SS 16, 102–03).

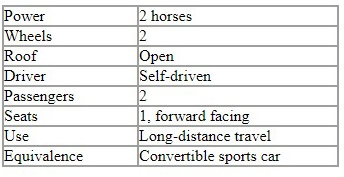

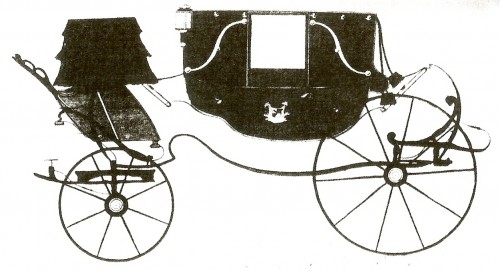

Barouche. R. Straus, Carriages and Coaches (1912)

Principal owners: Lady Catherine de Bourgh (PP), Edward Ferrars in Mrs. Ferrars and Fanny Dashwood’s fantasy (SS), Mrs. Palmer (SS), Henry Crawford (MP), and Lady Dalrymple (P).

Olsen writes that the barouche is “the supremely desirable vehicle for summer or for fair-weather travel around town.” It has a “long, shallow, curved body with a single hood that could be raised to cover the back passenger seat only—hence its unsuitability for rainy weather” (Olsen 1: 53). Its “lack of storage for luggage or cargo” makes it unsuitable for long trips (1: 54). The barouche is a stately, expensive carriage for the wealthy. The typical owners of the barouche in Austen’s novels are married women, with the notable exception of Henry Crawford.

Sir Walter Elliot and his daughter Elizabeth Elliot are all about appearances, as evidenced by their relationship with carriages. Jones notes that Sir Walter “maintains two pairs of expensive carriage horses as non-negotiable markers of baronet status” (19). To this end, they delay the sale of their chaise and four until after their journey to Bath; this “last office of the four carriage-horses” allows them to arrive in style and prevents their neighbors from knowing the extent of their debts (P 7, 35). One rainy day Elizabeth requests a ride in Lady Dalrymple’s barouche and, with the servant’s announcement, everyone in the shop hears “that Lady Dalrymple [is] calling to convey Miss Elliot” (P 174, 176). While being called for in Lady Dalrymple’s barouche is a social coup, Miss Elliot and Mrs. Clay do not escape getting wet because the barouche’s single hood only covers the forward-facing seat.

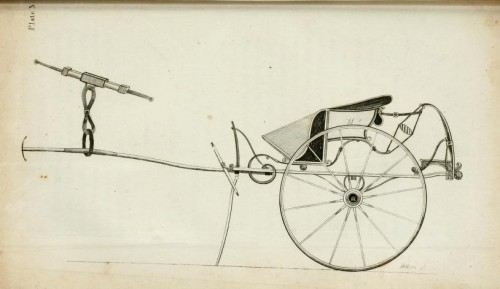

Curricle. W. Felton, A Treatise on Carriages, vol. 2 (1796)

Principal owners: Mr. Darcy (PP), William Goulding (PP), John Willoughby (SS), Mr. Rushworth (MP), Henry Tilney (NA), Charles Musgrove (P), and William Elliot (P).

“Curricles,” Felton writes, “were ancient carriages, but are lately revived with considerable improvements; and none are so much regarded for fashion as these are by those who are partial to drive their own horses; they are certainly a superior kind of two-wheeled carriage, and, from their novelty, and being generally used by persons of eminence, are, on that account, preferred as a more genteel kind of carriage than phaetons” (2: 95).

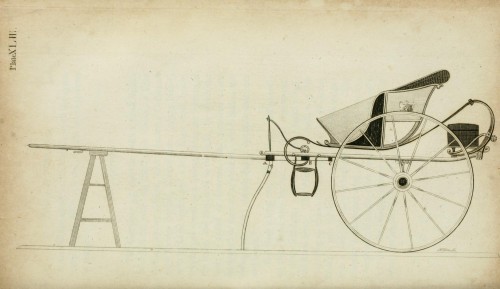

Austen contrasts characters who drive the fashionable curricle with those who drive the cheaper, more practical gig. Mr. Darcy and Henry Tilney drive curricles, while their erstwhile rivals, Mr. Collins and John Thorpe, drive gigs. John Willoughby prefers to drive the faster, more expensive, and fashionable curricle, rather than a more economic gig (SS 75). The consequence of his lifestyle is that he outspends his income; as Mrs. Jennings observes, Willoughby will need to marry an heiress and not the girl he loves (194). Heiress-hunting John Thorpe’s excuse for not owning the more expensive curricle is related to Catherine as a chance opportunity to purchase a gig from a friend as a favor. He appears to be conscious of the social difference when he describes the gig as “‘Curricle-hung you see; seat, trunk, sword-case, splashing-board, lamps, silver moulding, all you see complete’” (NA 46). These features may not be all that unusual; according to Felton, “Curricles being now the most fashionable sort of two-wheeled carriages, it is usual, in building a Gig, to imitate them, particularly in the mode of hanging” (2: 107). Other characters purposely choose the gig. One can only imagine that the less expensive gig was, as Jones observes, “chosen [by Mr. Collins] presumably because he and Lady Catherine consider it highly suitable for a clergyman in his position” (84). In contrast, the Crofts’ choice of the gig is both sensible and economical; they are unpretentious people who have no need for a fancier rig.

Gig. W. Felton, A Treatise on Carriages, vol. 2 (1796)

Principal owners: Mr. Collins (PP), John Thorpe (NA), young lawyers (SS), and the Crofts (P).

Felton describes gigs as “one-horse chaises, of various patterns, devised according to the fancy of the occupier; but more generally . . . the mode of hanging is what principally constitutes the name of Gig. . . . [A]ll one-horse chaises, that are neat and fancifully constructed, are named Gigs” (2:107).

Courtship and Carriage

David M. Shapard makes several observations about the relationship between new carriages and weddings. For those who could afford it, one of the customary wedding preparations in Regency England was the ordering of a new carriage (Shapard PP 203).3 He observes that it “was a mark of favor and affection for the bride, since she might have need of a carriage in her new home” (Shapard E 471). And, finally, that “the carriage would take the couple away after the ceremony and could display their wealth and good taste to everyone” (Shapard, SS 401). Marriages and carriages are certainly synonymous to Mrs. Bennet. Pleased with her matchmaking efforts after the Netherfield ball, she predicts there will soon be “settlements, new carriages and wedding clothes” (PP 103). Lydia’s impending wedding sets Mrs. Bennet again planning “those attendants of elegant nuptials, fine muslins, new carriages, and servants” (310). Even Mr. Bennet echoes his wife when he questions Elizabeth about her feelings for Mr. Darcy: “‘He is rich, to be sure, and you may have more fine clothes and fine carriages than Jane’” (376). Mrs. Bennet, upon learning of Elizabeth’s engagement, is less reserved: “‘What pin-money, what jewels, what carriages you will have!’” (378).

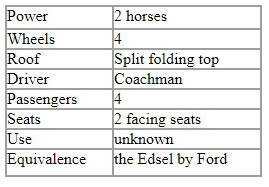

While none of the other novels is quite as effusive about marriages and carriages as Pride and Prejudice, Austen employs the connection between the two in all her novels. As Willoughby’s wedding to Miss Gray approaches, Mrs. Palmer passes on the gossip to Elinor Dashwood: “at what coachmaker’s the new carriage was building, by what painter Mr. Willoughby’s portrait was drawn, and at what warehouse Miss Grey’s clothes might be seen” (SS 215). When Anne marries Captain Wentworth, she becomes “the mistress of a very pretty landaulette,” which causes her sister Mary to suffer (P 250). Mr. Elton’s marriage is expected to be heralded in Highbury by a “new carriage, bell ringing and all” (E 267). All that fortune-hunting Isabella can think about on her engagement to James Moreland is “a carriage at her command, a new name on her tickets, and a brilliant exhibition of hoop rings on her finger” (NA 122).

Landaulette. R. Straus, Carriages and Coaches (1912)

Principal owner: Anne Elliot Wentworth.

Felton believes that demi-laundau or landaulette “has the same advantage as the Landau, only that the number of passengers are proportionably less, but, for convenience, where only one carriage is kept, none exceeds it for country use (2: 57). Funnily enough, the landau, which is described by Olsen as “essentially a coach with a roof that folded in two sections” (1: 121), does not appear in the six published Austen novels.

Waiting on a coach maker for the timely construction of a carriage becomes an obstacle for the rushed weddings of Maria Bertram and Mr. Rushworth and of Mr. Elton and Augusta Hawkins. Maria Bertram is in such a hurry to get married that she considers any delay to be “an evil” and decides that “the preparations of new carriages and furniture might wait for London and spring, when her own taste could have fairer play” (MP 202). The absence of the customary new carriage at the wedding (the only significant instance in all six novels)4 causes gossip in the neighborhood and foreshadows the dissolution of the marriage: “Nothing could be objected to when it came under the discussion of the neighborhood, except that the carriage which conveyed the bride and bridegroom and Julia from the church door to Sotherton was the same chaise which Mr. Rushworth had used for a twelvemonth before” (203). Likewise, Mr. Elton’s courtship of Augusta was hurried; she recounts how the inevitable delays in the carriage’s construction “‘did not proceed with all the rapidity which suited his feelings,’” causing him to despair: “‘The carriage—we had disappointments about the carriage;—one morning, I remember, he came to me quite in despair’” (E 308). Shapard explains Mr. Elton’s predicament: “people usually placed an order with a coachmaker, telling him the type and features they desired and then waiting for him to construct it. There was no mass production of vehicles then” (Shapard E 545). Like the Rushworths, the Eltons are eager to marry as soon as possible; but while Mr. Elton ensures that the customs are observed, Maria flouts tradition for expediency.

Tour de Barouche

Austen’s characters, not content to stay home, travel by carriage about the English countryside to see the sights: great houses, towns and spa-towns, beautiful vistas, and the sea. Except for Mr. Collins’s prosaic morning drives in his gig to show his father-in-law the countryside (PP 168), Austen utilizes most of these outings to facilitate some type of dramatic disruption.

Elizabeth’s extended tour of Derbyshire with the Gardiners in an unnamed horse-drawn vehicle includes a visit to Pemberley and provides her with a new view of Mr. Darcy (PP 238–41). Pemberley, with its carefully sculpted prospect, is first seen by Lizzie at its best advantage—from the carriage.5

They gradually ascended for half a mile, and then found themselves at the top of a considerable eminence, where the wood ceased, and the eye was instantly caught by Pemberley House, situated on the opposite side of a valley, into which the road with some abruptness wound. . . . Elizabeth was delighted. She had never seen a place for which nature had done more, or where natural beauty had been so little counteracted by an awkward taste. They were all of them warm in their admiration; and at that moment she felt, that to be mistress of Pemberley might be something! (PP 245)

This view of Pemberley marks a change in Elizabeth’s perception of its owner. Just when Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy begin to repair their acquaintance, the stay at Lambton is cut short by the news about Lydia’s elopement.

Some outings that are intended for pleasure end up sowing discord. Sir John Middleton frequently organizes daytrips in open carriages to Whitwell, a property owned by Colonel Brandon’s brother-in-law. Jones explains that “shorter trips more often than not relieved the tedium of everyday existence. . . . [T]hose with carriages at their disposal could be whisked off on relatively brief excursions of pleasure, to view celebrated country estates or local beauty spots” (139). Sir John promises his party that Whitwell offers beautiful grounds, a morning of sailing, and a picnic (SS 62). When the outing is canceled, Marianne and Willoughby drive off alone in his curricle, end up touring his aunt’s house, and lie about it; Mrs. Jennings finds out the truth by gossiping with the servants (66-67). When they are found out, Elinor confronts Marianne as to the impropriety of the visit, but Marianne defends her actions: “‘as we went in an open carriage, it was impossible to have any other companion’” with an appeal to moral sense—that since she was not sensible of impropriety, then she was not “acting wrong” (SS 68–69). Augusta Elton, to compensate for the delay of the Sucklings and their barouche-landau, organizes a two-day event of strawberry picking at Donwell Abbey, followed by the trip to Box Hill. As the picnic at Box Hill implodes, and everyone prepares to journey home, Mr. Knightley, finding Emma alone waiting for her carriage, chastises her thoughtless words to Miss Bates (E 374−75). The carriage ride home allows Emma to reflect on her behavior: “Emma felt the tears running down her checks almost all the way home, without being at any trouble to check them, extraordinary as they were” (376). Unlike Marianne’s visit to Allenham, which causes her delusion about Willoughby’s intentions toward her, the disastrous trip to Box Hill shows Emma her thoughtlessness toward others and begins her journey of self-discovery.

The outing to Sotherton is originally proposed so that Mr. Rushworth can solicit Henry Crawford’s advice about improvements to its grounds. Despite Mrs. Norris’s intention of leaving Fanny Price behind (MP 79), they eventually fit the entire party into Henry Crawford’s barouche with Edmund riding on his horse:

Happy Julia! Unhappy Maria! The former was on the barouche-box in a moment, the latter took her seat within, in gloom and mortification; and the carriage drove off . . . For the first seven miles Miss Bertram had very little real comfort; her prospect always ended in Mr. Crawford and her sister sitting side by side full of conversation and merriment; and to see only his expressive profile as he turned with a smile to Julia, or to catch the laugh of the other, was a perpetual source of irritation, which her own sense of propriety could but just smooth over. (80–81)

Various plans for seeing Sotherton’s grounds by carriage are proposed and rejected (84). Instead, the group is subjected to a stultifying tour of the house; when everyone scatters about the grounds (including Maria, who wanders off with Henry), the original object of the trip is forgotten.

Though Captain Wentworth originally introduces the subject of Lyme because of the residency of his friend, Captain Harville, it is Louisa Musgrove’s persistence that transforms it into a trip to the seaside, the ladies in the family coach and the men in Charles Musgrove’s curricle:

The first heedless scheme had been to go in the morning and return at night, but to this Mr. Musgrove, for the sake of his horses, would not consent; and when it came to be rationally considered, a day in the middle of November would not leave much time for seeing a new place, after deducting seven hours, as the nature of the country required, for going and returning. They were consequently to stay the night there, and not to be expected back till the next day’s dinner. (P 94–95)

While the pleasant outing ends in near tragedy with Louisa’s fall off the stairs on the Cobb, it rescues Wentworth from an ill-matched marriage.

Desperate Carriage Rides

Not only do daytrips in carriages prove unsettling, several novels include a desperate carriage ride. Whether it is to lodge a protest, travel home, collect a person, make a confession, or carry news, these journeys are stressful situations that reveal a traveler’s character or allow expression of feelings. While Austen is noted for being very careful about distances and travel times (Shapard PP 549), these journeys that require haste necessitate a discussion of horse speed and the post system. According to Shapard, a carriage with two horses traveling at a gallop could achieve a speed of seven to eight miles per hour, depending upon the quality of the road. Adding two more horses increased the speed to ten miles per hour; however, while more horses meant faster travel, the expense was greater (Shaphard, PP 351, 353). To travel by post, one could use a personal carriage or a hired carriage with “horses that were hired at posting stations, generally local inns, that existed approximately every ten miles along main routes. The horses would proceed at full gallop for this distance and then, upon arrival at the next station, be changed for a set of fresh horses that would gallop quickly for another ten miles” (Shapard MP 483).

When Lady Catherine learns that Mr. Darcy may marry Elizabeth, “‘a scandalous falsehood’” (PP 353), she speeds in all haste to Longbourn to confront her:

One morning . . . their attention was suddenly drawn to the window, by the sound of a carriage; and they perceived a chaise and four driving up the lawn. It was too early in the morning for visitors, and besides, the equipage did not answer to that of any of their neighbours. The horses were post; and neither the carriage, nor the livery of the servant who preceded it, were familiar to them. As it was certain, however, that somebody was coming . . . the conjectures of the remaining three continued, though with little satisfaction, till the door was thrown open, and their visitor entered. It was Lady Catherine de Bourgh. (351)

Lady Catherine travels the fifty miles to Longbourn in a hired carriage, sacrificing the comfort and conspicuous display of wealth of her barouche for the speed of the chaise and four (Shapard PP 675). Jones calls it “indicative of Lady Catherine’s sense of frustrated authority that she favours acceleration over appearances” (111).

Colonel Brandon travels to Barton Cottage so that Marianne can have her mother by her side while she is so ill. Using his own chaise and two hired horses, he “calculated with exactness the time” for Elinor to expect their return from the eighty-mile roundtrip (SS 311–12). Shapard observes that “this episode gives Colonel Brandon the opportunity to play an active, heroic role, particularly in relation to Marianne” (Shapard SS 581). Meanwhile, Willoughby, on hearing that Marianne is dying, drives his curricle with four horses 120 miles to Cleveland in a remarkable twelve hours, arriving at 8 p.m. (Shapard SS 561)—remarkable, because he had to be travelling over ten miles an hour. The purpose of his journey, he tells Elinor, is to apologize for his behavior—he does not want Marianne to die thinking him a villain (SS 330–31). Colonel Brandon’s carriage arrives bearing Mrs. Dashwood a mere half hour after Willoughby leaves and an hour earlier than expected because Mrs. Dashwood, ignorant of his errand, had already prepared to leave for Cleveland that day (333, 335). These overlapping journeys allow the reader to marvel at the speed of the travel and at the motives of each man: Brandon, who unselfishly wishes to provide comfort and relieve suffering for others, and Willoughby, who selfishly desires, if not forgiveness, at least understanding.

Post-chaise. W. Felton, A Treatise on Carriages, vol. 2 (1796)

Principal users: Mrs. Long (PP), Elizabeth Bennet and Maria Lucas (PP), George Wickham and Lydia Bennet (PP), Mrs. Jennings (SS), Dr. Davis, Lucy and Nancy Steele (SS), Robert Ferrars (SS), Frank Churchill (E), William and Fanny Price (MP), Edmund Bertram, Fanny and Susan Price (MP), Catherine Morland (NA), Captain Wentworth, Anne Elliot, and Henrietta Musgrove (P), and Charles Musgrove (P).

A chaise could be privately owned or hired. The hired post-chaise was painted canary yellow and driven by a postilion who rode one of the horses. According to Jones, a post-chase with two horses cost 1 shilling and sixpence per mile, while the postilion cost only 3 pence per mile (110). The post-chaise was used by people not wealthy enough to own a carriage but too refined to take the public coach. Austen uses the term “hack chaise” in Pride and Prejudice for Mrs. Long’s local rental, “hackney coach” when Lydia and Wickham move to local transport, and “hack post-chaise” in Northanger Abbey for Catherine’s precipitous journey home. Olsen observes that “There is always something vaguely tacky about hack vehicles in Austen. When she wants to convey a sense of comfortable, sophisticated travel, she uses the phrase ‘post-chaise’ or something similar. Hackney coaches are associated with poverty, disgrace, anonymity, and disappointment” (1: 112).

Catherine has her gothic adventure, but, like her “kidnapping,” it is fortunately not the stuff of high drama: she is sent from Northanger Abbey with little warning, without a proper escort, without any money (except what Eleanor wisely gives her), in a post-chaise, without any proper idea of how to get home, and on a Sunday (NA 223–29). She is said to be “too wretched to be fearful” but that “[s]he met with nothing, however, to distress or frighten her. Her youth, civil manners and liberal pay, procured her all the attention that a traveller like herself could require” (230, 232). After an eleven-hour trip, she arrives safely home, not as a heroine in the splendor of servants and carriages but a “heroine in a hack post-chaise” (232). Though Catherine’s journey had all the potential for mishap, as Mrs. Moreland concludes: “‘it is a great comfort to find that she is not a poor helpless creature, but can shift very well for herself’” (237).

She Hath Spoken

Jones observes that several women in the novels use carriages “to exert control” over others (93). For benevolent, hateful or selfish reasons, these women use carriages to limit the mobility of other female characters (Jones 93-96, 98). Mrs. Bennet uses the family coach as a vehicle of matchmaking. By denying Jane the use of the carriage, she ensures that her daughter will have to stay at Netherfield and thereby increase her contact with Mr. Bingley (PP 30–31).6 Mrs. Bennet delays calling for the carriages after the ball at Netherfield, and the Bennets end up being the last guests to leave, ensuring that Jane and Mr. Bingley get more time together (102–03).

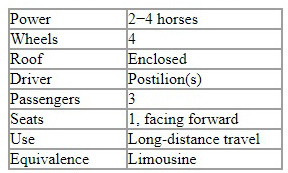

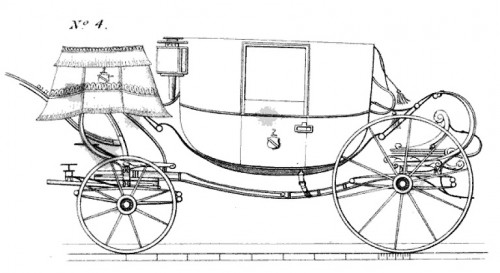

Coach. T. Fuller, An Essay on Wheeled Carriages (1828)

Principal owners: the Bennets (PP), Lady Catherine de Bourgh (PP), the Richardsons (SS), the Middletons (SS), the John Knightleys (E), the Musgroves (P), and possibly Mr. Woodhouse (E).

Felton writes that “[c]oaches have the most uniform appearance of any other carriage; and, for families, are the most convenient of any in use, as they can accommodate twice the number of passengers at one time” (2: 32). Shapard describes them as the “largest and most expensive of all carriages” (PP 57). Olsen explains that a coach is like “a van or a minivan . . . a serviceable, practical, but not especially speedy or flashy way to get a large number of passengers from point A to point B” (Olsen 1: 116).

Among the manipulating women mentioned by Jones, Lady Catherine de Bourgh is a surprising lightweight. Of course, she does control the endings of the evenings at Rosings Park, but then Mr. Collins is so grateful to ride in her carriages, what can Mrs. Collins object to? She also tries unsuccessfully to get Elizabeth to extend her stay: “‘Oh! your father of course may spare you, if your mother can.—Daughters are never of so much consequence to a father. And if you will stay another month complete, it will be in my power to take one of you as far as London’” (211). Shapard questions the generosity of this offer since London is only twenty miles away (Shapard PP 413).

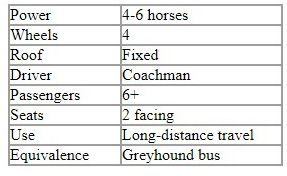

Stage coach. G. A. Thrupp, The History of Carriages (1787)

Principal users: Mrs. Dashwood’s servants (SS), Mrs. Jennings’s servant, Betty (SS), probably Lucy and Anne Steele (SS), almost Fanny Price (MP), William Price (MP), and Robert Martin (E).

The use of stage coaches in England began in 1640 (Thrupp 102). With a coachman and a guard, they were designed to carry up to six passengers and luggage, and sometimes the mail. The public stage coach was used by servants and the poor.

Mrs. Norris is both parsimonious and controlling. Of Mrs. Norris, Austen writes, “her love of money was equal to her love of directing” (MP 8). Her dislike of Fanny Price and her frugality are immediately apparent when she suggests to Sir Thomas that “‘[t]hey may easily get her from Portsmouth to town by the coach, under the care of any creditable person that may chance to be going. I dare say there is always some reputable tradesman’s wife or other going up’” (8). This hostility continues into Fanny’s adulthood, such as when Mrs. Norris tries to keep Fanny from joining the carriage ride to Sotherton (79). Then, to compound the injury, Mrs. Norris tells Fanny, as they are leaving Sotherton, “‘I am sure you ought to be very much obliged to your aunt Bertram and me, for contriving to let you go’” (105). Mrs. Norris uses the excuse of economy to deny Fanny access to the carriage, and yet she does not employ that same rule for herself (221). During her instructions on Fanny’s expected behavior at the Grants’ dinner party, Mrs. Norris tells Fanny she is “‘the lowest and last.’” She continues, “‘And if it should rain, which I think exceedingly likely, for I never saw it more threatening for a wet evening in my life—you must manage as well as you can, and not be expecting the carriage to be sent for you. I certainly do not go home to night, and, therefore, the carriage will not be out on my account’” (221). When Sir Thomas countermands her will, Mrs. Norris becomes agitated and “red with anger” (221).

Barouche-landau. Le Beau Monde (1806)

Principal owners: the Sucklings (E).

The barouche-landau is “purported to have features of both the barouche and the landau,” but, according to Olsen, “It was not a popular innovation” (1: 405). Does this choice of carriage itself speak to the elusiveness of the Sucklings in Emma, always promised, but never realized?

Augusta Elton determines to manage Jane Fairfax, not just in her place of employment but in her movements around Highbury. She suggests to Emma that “‘a vast deal may be done by those who dare to act. You and I need not be afraid. If we set the example, many will follow it as far as they can; though all have not our situations. We have carriages to fetch and convey her home, and we live in a style which could not make the addition of Jane Fairfax, at any time, the least inconvenient’” (E 283). When the Eltons forget to bring Miss Bates and Jane Fairfax to the ball at the Crown, Mrs. Elton makes the odd remark about the “‘pleasure [of] . . . send[ing] one’s carriage for a friend’” given that she has just forgotten them. She reassures Mrs. Weston that she need not offer her carriage again as Mrs. Elton will ensure that they are taken care of (320-21). Augusta even promises to find a place for Jane in the Sucklings’ barouche-landau when they finally visit (284). Jones observes, “Mrs. Elton puts kindness to Jane out of anyone else’s power: to Hartfield, to Donwell, to Box Hill, Jane must submit to being taken by Mrs. Elton” (95).

Likewise, Emma exerts physical control over Harriet’s movements. When Harriet needs to return a visit to Abbey Mill, Emma determines to drive Harriet in her carriage and then promptly pick her up fifteen minutes later, “as to allow no time for insidious applications or dangerous recurrences to the past, and give the most decided proof of what degree of intimacy was chosen for the future” (185). Emma also sends Harriet to London in her father’s carriage, ostensibly to visit a dentist, but really to distance her from Emma and Mr. Knightley. This manipulation, through no design of Emma’s (but possibly of Mr. Knightley’s), results in Harriet’s reunion and subsequent marriage to Robert Martin (451, 470–72).7

While Augusta Elton controls Jane Fairfax’s access to carriages, Emma only attempts to. Learning about Jane’s poor health, Emma offers an airing in her carriage, but when she hears that Mrs. Elton, Mrs. Cole, and Mrs. Perry have ignored Jane’s wishes to be alone, Emma realizes that she does “not want to be classed with . . . [the women] who would force themselves anywhere” (390–91).

Carriage (noun): “the outward manifestation of personality or attitude”

One of Merriam Webster’s definitions of the word carriage is “the outward manifestation of personality or attitude” (“Carriage”). It is no wonder, then, that Austen employs carriages in her novels to illustrate a person’s character. Austen, at times, pairs characters to show their opposing virtue and vice: Mrs. Jennings’s generous offer that “her carriage was always at Elinor’s service” (SS 294) is contrasted with Fanny Dashwood, who would not even ride in the same carriage with her sisters-in-law (248-49); John Thorpe, a braggart and a liar, does not compare well with Mr. Tilney, who is neither a flashy nor boastful driver (NA 157); and Willoughby and Colonel Brandon each drive considerable distances, one for personal gratification, the other for love (SS 318, 330–31, 337).

Town chariot. T. Fuller, An Essay on Wheeled Carriages (1828)

Principal owners: Mrs. Jennings (SS), Mrs. John Dashwood (SS), and Mrs. Rushworth (MP).

Olsen describes the chariot as being “identical to the coach except that it had only a forward-facing seat” (1:121). If the coachman’s box were removed, it would be a chaise.

From the arrival of the Elliots in Bath to the departure of General Tilney, their chaises and four, emblazoned with their arms, are displays of vanity. Mrs. Morland concludes that General Tilney may look like a gentleman, but he does not behave like one: “[he] had acted neither honourably nor feelingly—neither as a gentleman nor as a parent” (NA 234). Kirstin Olsen thinks Crawford’s ownership of a barouche apt: “it is a fair-weather conveyance, and he turns out to be a fair-weather gentleman, unable to bear real hardship or frustration to win Fanny’s love” (1:53–54); he is inconstant. Mrs. Norris uses the excuse of economy to deny access to carriages for Fanny, and yet she does not employ that same rule for herself (MP 221). The Steele sisters exploit every advantage to gain free rides from Dr. Davis or future rides from Colonel Brandon (SS 218, 294); Lucy, in a post-chaise with Robert Ferrars, deceives Elinor into believing she had married Edward (354); and Lucy steals Anne’s money, leaves her stranded in London, and does not offer her a ride home in the post-chaise (370–71; Olsen 1:135). Among Thorpe’s many lies to Catherine is his fabrication of having seen Henry Tilney driving with a woman in a phaeton (NA 85). Fanny Dashwood greedily convinces her husband to limit the support for his stepmother and half-sisters as promised, reducing them to genteel poverty: “They will have no carriage, no horses, and hardly any servants” (SS 12).

Phaeton. G. A. Thrupp, The History of Carriages (1877)

Reported user: Mr. Tilney, according to John Thorpe, who tells Catherine he has seen him driving a phaeton with a woman.

According to Olsen, “around the time Jane Austen reached adulthood,” the phaeton was superseded by the curricle as “the height of style” (1: 332). It is high sprung, fast, and because the seat can be placed over the front axle, it is liable to tipping over.

The virtues displayed by Austen’s characters, like the vices, are not distinct categories; they necessarily overlap. Mr. Palmer is a curiously dour man, and yet he exhibits surprising kindness toward his vivacious wife when he surprises her with a visit to see her mother and sister at Barton (SS 110). Lady Russell takes Anne in her carriage with the family arms on the door to the unfashionable Westgate-buildings to visit her friend Mrs. Smith, of whom Anne’s father is so contemptuous (P 157–58). Mr. Knightley, who very rarely uses his carriage, kindly pulls it out on the night of the Coles’ party for Miss Bates and Jane Fairfax. As Emma explains: “‘He is not a gallant man, but he is a very humane one’” (E 213–14, 223). Elinor wisely says of Colonel Brandon’s drive to Barton and back that his character “‘does not rest on one act of kindness, to which his affection for Marianne, were humanity out of the case, would have prompted him’” (SS 337). Perceiving Anne’s fatigue during a long walk, Wentworth ensures that she rides home in the Crofts’ gig (P 91). Seated beside them, she is able to observe their manner of driving: the Admiral at the reins with Mrs. Croft deftly providing timely direction without criticism, “which she imagined no bad representation of the general guidance of their affairs” (92).

![]()

All this talk of carriage owning gives the modern reader a false impression. As Olsen observes, “Though carriages seem to be everywhere in Austen’s writings, they were actually rather uncommon in the England she inhabited. They were simply too expensive for most people to keep” (1: 128). Despite the rarity of carriages in Regency England, Jane Austen utilizes horse-drawn vehicles like a master coachwoman. They are so much more than a mode of transportation: she uses them to drive the plot and reveal character, for comic relief or dramatic effect—anything to convey her characters where she needs them to go.

NOTES

1This paper is a sampling of Austen’s uses of carriages. She also writes about women riding alone with men, conversations in carriages, the sound of carriages, gossip surrounding carriages, etc.

2David M. Shapard explains that less than one percent of the population had an income of two thousand a year (SS 173).

3Austen started this theme of carriages and marriages in a novella of her juvenilia, “The Three Sisters,” in which Mary writes of an argument she has had with a suitor who wants to marry her: “‘And he promised to have a new Carriage on the occasion, but we almost quarrelled about the colour, for I insisted upon its being blue spotted with silver, & he declared it should be a plain Chocolate; & to provoke me more said it should be just as low as his old one. I wont have him, I declare’” (MW 58).

4Robert Ferrars’s marriage to Lucy Steele may be the other exception.

5This parallel reminds the reader of Darcy’s observation: that a lady’s figure is best seen from a proper distance (56).

6Mrs. Bennet’s excuse, that the horses cannot be spared from their use on the farm, is not contradicted by Mr. Bennet even though there should not be a lot of active farming in November and on a rainy day.

7Curiously, this is nearly the only instance of the carriage being used where Mr. Woodhouse’s concern for the carriage, horses, or coachman, James, was not recorded.