When we think of Jane Austen, we usually visualize the incomplete portrait her sister drew of her, the one her family commissioned after her death, or perhaps her new statue in Basingstoke. To these more traditional portraits of Austen, however, have been added, in the last few years, more unexpected and unconventional ones by modern artists. What would Austen look like, for example, reimagined as a witch, an action figure, or as a Star Wars Jedi Guardian? What can these different portraits tell us about the ways in which we are reimagining Austen today?

Unfortunately for us Austen fans, she is the only member in her family, apart from her brother George, who was not raised with the other siblings, to have had no formal portrait in her lifetime, unless we consider two portraits which have not been attributed to Austen with certainty. The first is known as the “Rice Portrait,” owned by the Rice family, descendants of Austen’s brother Edward Knight. The portrait shows a young woman with short hair and a white dress posing with a parasol in her right hand against a background with an autumnal landscape and stormy skies. Allegedly painted by Ozias Humphry in 1788, Austen biographer Deirdre Le Faye, among other experts, has dated its origin to 1805–1806 and identified the sitter as Mary Anne Campion (1797–1815), eldest daughter of Austen’s second cousin, also named Jane Austen (1776–1857) of Kippington near Sevenoaks in Kent.

|

|

|

The Rice portrait (ca. 1805–1806) and the Byrne portrait (ca. 1815) |

|

The second is known as the “Byrne Portrait” because owned and made famous by Austen biographer Paula Byrne. This “portrait of a writer at work,” as Byrne describes it, shows a woman writing at a desk against the background of St. Margaret’s Church and the edge of Westminster Abbey, near where, between 1813 and 1815, Austen paid long visits to her brother Henry, who lived in London’s West End (306). The woman herself wears a cap and a dress with long sleeves and has the dark curly hair and long nose that match Cassandra Austen’s portrait of Austen. Interestingly, the portrait contains a cat, an animal associated with singlehood, resting next to the woman as she writes. The inscription “Miss Jane Austin” at the back would appear to indicate with little doubt that the subject is Austen; however, this could have been an erroneous later addition (Byrne 307). As Deborah Kaplan has argued, “If the portrait is genuine, it would certainly fulfil the role of relic, testifying to Austen’s presence in or around 1815, when she sat before someone who was carefully putting graphite and ink on vellum” (Kaplan, “There She Is,” 131).

By Cassandra Austen (c. 1810). National Portrait Gallery, London. Wikimedia Commons.

The only certain portrait of Jane Austen taken during her lifetime is a small pencil and watercolor sketch made by her sister and closest friend, Cassandra, completed around 1810, so small—in fact, only 114 x 80 mm—that even though years ago I visited the National Portrait Gallery especially to see it, I walked past without noticing it at first. It did not become a favorite among the Austen family, and it was considered inadequate and unflattering by those who had known her in life (Tomalin, following 76). The Austen we see through Cassandra’s eyes stares sternly away from us, her focused eyes combined with her crossed arms depicting her as sure of herself, wilful, and tough. The fact that this portrait was drawn in life by the person who knew her the best out of all others says much: Cassandra clearly saw her sister as a confident, defiant person.

|

|

|

Watercolor by James Andrews (left) and engraving by William Home Lizars (right). |

|

When he was about to publish his 1869 A Memoir of Jane Austen, the first full biography of Austen, her nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh sent Cassandra’s sketch to an artist, James Andrews of Maidenhead. The watercolor Andrews made from Cassandra’s sketch subsequently formed the basis of a print engraved by William Home Lizars for the frontispiece of Austen-Leigh’s biography. While certainly lacking the incompleteness of Cassandra’s sketch, this watercolour and the subsequent engraving have been much criticized for softening Austen. The fierceness in Cassandra’s sketch is lost in the other two portraits in which Austen stares blankly into space. The defiance in her stare is missing, as is the disruptive potential of her arms-crossed stance. While offering a much more complete picture than Cassandra’s portrait of what Austen might have looked like, it matches James Edward’s portrait of his “Aunt Jane” as a perfectly conventional woman, devoted to domestic life above all, and caring nothing about money and fame. In attempting to present a version that removed any possibility of scandal due to Austen’s status as an unmarried woman who wrote professionally, James Edward offered us a version of Austen in no way supported by the image we get from her letters.

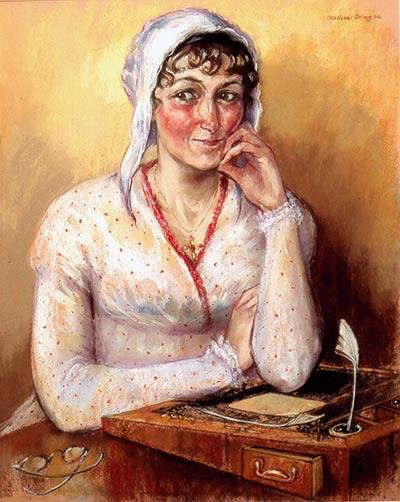

By Melissa Dring (2001). Jane Austen Centre, Bath.

In 2001, 185 years after her death, the Jane Austen Centre in Bath commissioned a new portrait from a perhaps more unlikely artist: Melissa Dring, trained as a portrait painter by the Royal Academy Schools in London and as a Police Forensic artist by the FBI in Washington, D.C. Dring aimed to give us a younger Austen. The Jane depicted by Cassandra would have been around thirty-five, and Dring’s challenge was to depict her during her Bath years, when she would have been aged between twenty-six and thirty-one. Using source material and forensic methods, Dring gave her the long nose and narrow mouth her siblings shared in their portraits, as well as the brunette hair with a rich color and the rosy cheeks (maybe a little too rosy!) she was described as having by people who had known her in life. She is also portrayed wearing her cap, which her nephew Edward described as a garb of middle age and unmarried status that both she and her sister adopted before, he considered, their years required (77). To Dring the adoption of the cap sounds “a touch old-maidish,” but we can read it differently, as a symbol of defiance against a patriarchal society that would have expected her to marry and devote herself to domestic pursuits instead of her writing.1 Austen’s decision to remove herself from the marriage market when she would have been expected to marry and her dedication to her writing (and writing for profit on top of that) when, as her nephew’s portrayal indicates, her priorities as a genteel woman were expected to lie elsewhere demonstrates a lack of concern for patriarchal expectations that is nothing if not subversive. In this portrait, Austen wears a mischievous look that Dring purposely meant to contrast with the more serious one in Cassandra’s sketch. This mischievousness brings to mind the Austen who, at age thirty-seven, wrote in her letters: “By the bye, as I must leave off being young, I find many Douceurs in being a sort of Chaperon for I am put on the Sofa near the Fire & can drink as much wine as I like” (6–7 November 1813). Depicted here with her writing desk, Austen is portrayed first and foremost as a writer.

By Adam Roud (2017), Basingstoke.

Fifteen years later, as part of the celebrations for the two-hundredth anniversary of Austen’s death, we get a long overdue statue of Austen in Basingstoke, made by local artist Adam Roud. Having lived for twenty-five years of her life in Steventon, in the Hampshire countryside, before her father’s retirement and the family’s move to Bath, Austen frequently visited Basingstoke, the nearest town. In this life-sized statue, the fierceness in her eyes from Cassandra’s portrait is back, Austen’s contribution to literature represented by the book she holds under her left arm. This Austen is intent on something, in motion, holding her coat so that it does not impede her walking, the determination in her eyes matching that of her implied movement. As Adam Roud explained while his work on the statue was still ongoing: “I don’t want her on a plinth, I plan to have her just walking in the street so that we are walking with her” (“Jane Austen Statue”).

We do not have to look very hard, however, to find very different portraits of Austen. As a Romantic-period British author of pretty much incomparable popularity, Austen is very much an exception to the rule of approaching portraits of canonical British authors solemnly. Austen fans have completely punctured the idea that solemnity is the only way to go; instead, Austen is the perfect example of the benefits of approaching a canonical author from a place of humor. The Reading the Romantic Ridiculous project, on which I worked with Andrew McInnes at Edge Hill University, considers authors of this period through the lens of humor, aiming to take Romantic Studies from the sublime to the ridiculous. By moving away from the myth of the solitary genius, we present the ridiculous as an alternative to the sublime, privileging collective laughter above solitude and selfishness, reflecting on these ideals through our writing.

By Dr. Laura Eastlake. Reproduced with permission.

That approach to Romantic-period authors through laughter rather than solemnity is, of course, reflected in portraiture. On moving to Liverpool to work as part of this project, I received a welcome present from my colleague Laura Eastlake in the form of an Austen portrait. (Allow me a little bias when I say that this is my favorite Austen portrait of all.) Sitting comfortably across a yellow couch, Austen wears her characteristic cap—symbol of her proud and self-assured choice of singlehood—but this time the ribbon on it is a bright pink one matching the one around her neck, in striking contrast to the demure light blue in James Andrews’s version. This bright pink matches that of her socks, peeking from underneath her dress as she rests on the couch in a relaxed pose, as if she does not have a care in the world. She is enjoying a bucket of popcorn, taking a break by watching a movie rather than finishing all her unpacking at once. The bucket of popcorn is also a nod to the level of fame Austen has obtained due, in great part, to modern film and TV adaptations of her work. The bright colors—yellow sofa and bright pink and green cushions and book covers—nod to modern adaptations of Austen’s novels like Clueless (1995), which utilizes a similarly bright and joyous color palette. But lest we forget what started it all, she relaxes next to a pile of books sitting on a box clearly marked “Books,” which she will undoubtedly enjoy reading while lying on her comfortable new yellow couch. My move to Liverpool marked the first time I would live completely by myself, and my joy and sense of pride are perfectly encapsulated in Austen’s self-assured smile. Here, we find a combination of the fierce determination in Cassandra Austen’s portrait and the mischievous joy in Melissa Dring’s version.

Jane Austen Action Figure from Accoutrements, Inc.

Other less personal but also very fun modern depictions of Austen reflect the ways in which she has been reimagined for today’s modern audience, particularly young people. The number of recent young adult novels that reimagine Austen’s works, particularly Pride and Prejudice (1813)—such as Alice Oseman’s Solitaire (2014), Ibi Zoboi’s Pride (2018), and Nikki Payne’s Pride and Protest (2022), as well as new media series such as The Lizzie Bennet Diaries (2012) and Emma Approved (2013) for YouTube, make Austen’s novels accessible to young people in new and engaging ways. As a result, we have seen the appearance of new portraits of Austen that reflect the humorous ways in which audiences approach her and her work today. The Austen action figure comes with a book—Pride and Prejudice, of course—and removable quill pen. Austen is wearing white and bright pink (though earlier versions dressed her in a green spencer), another possible nod to adaptations such as Clueless, through which we have started associating a brighter color palette with Austen.

As Deborah Kaplan has argued, “Austenmania has prompted a renewed awareness of the power of audiences to determine the status and meaning of literary works, to construct, in this case, very different Austens” (4–5), and Allison Thompson agrees, stating that “Certainly the merchandise purchasable in the Austen franchise amply demonstrates the very different Austens that fans can create.” What is also significant is that, like Adam Roud’s statue, Austen is not static but in movement, as indicated by the forward position of her left leg and the bright pink shoe poking out from underneath her dress, this physical movement a symbol for Austen’s quick wit and independence of mind. She is, as we have become used to seeing her, wearing her characteristic cap, yet another symbol of her defiance of convention through her choice of singlehood. I do not currently own one of these action figures—and yes, I very much want to change this as soon as possible.

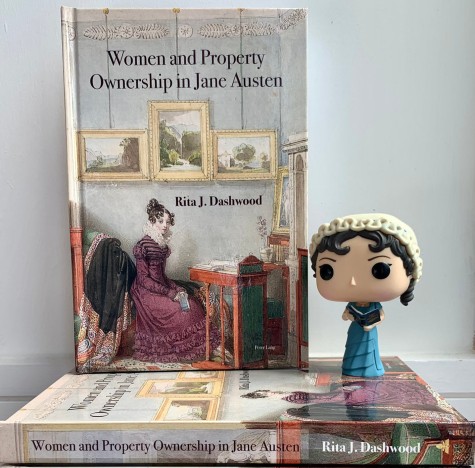

Funko Pop! Jane Austen.

Austen also has her own Funko Pop! Figure—one of many series of small collectible figurines known for their exaggerated features, including giant bobbleheads and oversized eyes. She wears a white cap with a dark blue ribbon and a blue dress, a nod to one of the versions of James Andrews’s watercolor in which Austen is depicted in a dress of the same color. In her hands, she holds a copy of Pride and Prejudice in a navy-blue tone and decorated with a peacock feather, a reference to the famous 1894 peacock edition of Pride and Prejudice illustrated by Hugh Thomson. This version of Austen depicts her first and foremost as the author of Pride and Prejudice, her most famous work, and that for which most people will know her. Austen thus joins the diverse group of authors who have their own Funko Pops!, including Bram Stoker, Stephen King, and Edgar Allan Poe. If having a figure with an oversized head in your likeness marketed to a wide audience is not a sign that you have reached a peak in your level of fame, I do not know what is. I am a big fan of this figure, having even used it to publicize my first book on Austen.

By Jeanne Beauchamp (Pilalire on Etsy). Reproduced with permission.

Other portraits will seem more unfamiliar. In French artist Pilalire’s adaptation of James Andrews’s portrait, Austen wears a blue dress as she does in Andrews’s version. That, however, is where the similarities end. The look on her face could not be more different: the determination in her eyes, together with the raised eyebrow, calls to mind the defiance in Cassandra’s portrait and distances us from the serene look in Andrews’s version. Even more strikingly, Austen’s raised left arm rests against the cover of a book—not Pride and Prejudice but a book of shadows. Identified by the pentacle, a symbol of witchcraft, on its cover, this book is where a witch writes down instructions for magical rituals. The pink and blue bookmarks, most likely marking Austen’s favorite spells, indicate that it has been put to use. Surrounded by flowers and her quill pen—symbols of femininity and nature and her vocation as a writer—Austen wears not her usual cap but a witch’s hat, its point stretching high above her head. The star- and moon-shaped chimes hanging outside her window add even more of a magical quality to the portrait, as does the large tree directly outside of the window, a reference to a witch’s close connection to the natural world. Even the fingerless gloves Austen is wearing—which add a Tim Burtonesque element to the portrait—are decorated with crescent moons and stars, another nod to a witch’s connection to the cosmos. The decision to portray Austen in this manner aligns with the association between literary women and witches, such as, for example, in the Literary Witches Oracle designed by Taisia Kitaiskaia, a Russian-American author, poet and tarot reader, and Katy Horan, a North-American artist.

But why witches? From the days of the Salem trials to our own period, witches have been a symbol of female power, female persecution, and feminist resistance. As Kristen J. Sollée argues, the contested identities of feminist and witch inform young women today as they counter a history of misogyny with empowerment (8–10). In this sense, millennial women’s growing interest in the figure of the witch, in particular the renewed associations of feminism with witchcraft, constitutes a form of resistance to patriarchy and its consequent misogyny that women continue to face today.

Linking a classic author like Austen and witchcraft is, therefore, part of a wider association between Austen and feminism. Zoboi, the author of the young adult novel Pride: A Pride and Prejudice Remix mentions Austen in her acknowledgements: “Austen gifted us with a story not only about love and class, expectations, and a woman’s place in the world. Even as she, a woman in nineteenth-century England, had the audacity to write, observe, and speak truth to power with such wit, humour, and grace” (291–92). Zoboi recognizes the relevance that Austen’s literary work continues to hold for younger generations who have seen expectations for an equalitarian society, both in terms of gender equality and social equality, unfulfilled.

By Kelly Light, Instagram account @KElight. Reproduced with permission.

Acknowledging Austen’s writing as speaking “truth to power” in its depictions of gender and class, thus constituting a form of resistance to an oppressive system, links Austen to another perhaps unexpected figure: the resistance fighter from Star Wars. Kelly Light’s sketch depicts Austen wearing a cap, loose locks of hair flowing in the wind, as she stands with her blue lightsaber ready to fight. The determination in her eyes and the implied movement in some of the previous modern portraits finds its apotheosis here. The blue lightsaber, most commonly wielded by Jedi Guardians, who represent the light in the moral fight against the dark side of the Force, thus symbolizes her righteousness. More significantly, it associates Austen with the Resistance, the group in the Star Wars universe that opposes the First order, a military dictatorship threatening democracy in the galaxy. This portrait therefore associates Austen with good and empowerment, placing her alongside such formidable female characters in the Star Wars universe as Princess Leia and Rey, who inspire rebellion.

In these more recent, more humorous portraits of Austen, we find ways of engaging with her work and its legacies that take us away from the solemnity usually associated with Romantic-period authors and invite us, instead, to approach it with lightness and laughter. Whether through witchcraft or Star Wars, these portraits offer us ways of thinking about Austen in connection to the most influential popular culture phenomena of our time. Perhaps most importantly, they also constitute a distancing from the misleadingly conventional Victorian representations of Austen and a return to the woman Cassandra was portraying in her original sketch of her sister: wilful, self-assured, and whose piercing eyes and defiant pose can be seen as an invitation to rebellion.

NOTES

1See “How Melissa Dring Created Her Forensic Austen Portrait.” After the early death of her fiancé, Cassandra had allegedly vowed to never marry anyone, marking the final nail in the coffin of Austen’s at best half-hearted efforts to get married.