Jane Austen has long been regarded as a quintessential part of Britain’s heritage. Recent updates of Austen’s novels, however, demonstrate that her plots and characters can move far beyond the confines of the early nineteenth-century English village and allow reflection on the continuities and discontinuities between Austen’s milieu and our own. In keeping with current concerns, in the past five or six years, major publishing houses like Penguin, HarperCollins, and Scholastic have brought out several Austen retellings that break new ground by reaching out to people of color and those with immigrant backgrounds.

Such reworkings of Austen through multicultural lenses reflect the world we live in and serve as a bridge between cultures. They make it easier for readers, especially younger ones, who have no genetic connection to the United Kingdom or Europe to see themselves in her stories. Also, as Austen adaptations have a built-in audience, these novels can serve as cultural introductions to those who know the original novels intimately but are less familiar with the practices of the many communities that make up their nations. Rather than being just an exemplar of English heritage or a favorite author of Anglophiles everywhere, Jane Austen is now speaking to a more inclusive audience.

In this essay, we will first discuss the film traditions that have shaped the development of the multicultural Austen update. We will then survey several recent novels, limiting our scope, for reasons of space, to versions of Pride and Prejudice set in multicultural communities in the United States. Such novels are not exclusive to the U.S., and the story of Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy is not the only one adapted. We point interested readers to novels in our bibliography by Farah Heron, Uzma Jalaluddin, and Ayisha Malik (immigrant communities in Canada, England), Soniah Kamal, Mahesh Rao, and Laleen Sukhera (settings in Pakistan, India); and Sarah Dass (setting in Tobago).

Our survey begins with film because the older dynamic of text’s shaping film has become more fluid. Film now also shapes text. Austen’s novels are sparing of description: we rarely know what Elizabeth or Darcy are wearing or eating, but the celebrated adaptations of 1995 and 2005 have imprinted on our minds precise images: what the Bennet family eats for breakfast, what Pemberley looks like, what Mr. Darcy is wearing (or not wearing). As a result, a visual rather than verbal imagination shapes how we see the culture of Regency England in our minds, and the updated Austen novels take into account that shift to the material.

In Autumn de Wilde’s gorgeous film Emma. (2020), we see a classic heritage treatment of Austen’s world in living color. There is an astonishing attention to the material conditions and practices of the Regency world, especially in the stunning, historically accurate, and colorful costumes worn by Anya Joy-Taylor and others. The film looks highly realistic with its grand display of color, fabric, and stuff. It out-heritages heritage drama with its close attention to the visual. Nevertheless, as we look back on the film a few years later, we cannot help but notice that it looks just a little old-fashioned. The heritage hyperrealism seems dated after the theatricalesque adaptations that follow it, and its all-white cast already seems a thing of the past.1

In Autumn de Wilde’s gorgeous film Emma. (2020), we see a classic heritage treatment of Austen’s world in living color. There is an astonishing attention to the material conditions and practices of the Regency world, especially in the stunning, historically accurate, and colorful costumes worn by Anya Joy-Taylor and others. The film looks highly realistic with its grand display of color, fabric, and stuff. It out-heritages heritage drama with its close attention to the visual. Nevertheless, as we look back on the film a few years later, we cannot help but notice that it looks just a little old-fashioned. The heritage hyperrealism seems dated after the theatricalesque adaptations that follow it, and its all-white cast already seems a thing of the past.1

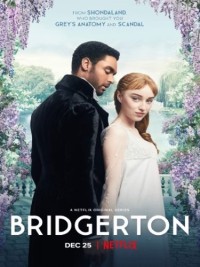

The turning point for filmed adaptations was Bridgerton, an Austen-adjacent series released on Netflix in December 2020. Based on Julia Quinn’s historical Regency romance The Duke and I (2000), the series was unusual in employing color-conscious casting, which necessitated its adapters’ inventing an alternative history of England to explain the centrality of Blacks in the highest levels of English society in the early nineteenth century (Regé-Jean Page portrayed the Duke and Golda Rosheuvel was Queen Charlotte).2 The series is as visually gorgeous as Emma. from earlier in the year, but it also consciously avoids the “heritage” feel typical of period drama. Highly stylized costumes in anachronistic fabrics and colors, over-the-top hairstyles for the Queen, and a score that combines both pop and period music gives Bridgerton a theatrical look that melds modern and Regency cultures. In the process, it opened a space for multiculturalism in period drama by loosening up artistic approaches for film.3

The turning point for filmed adaptations was Bridgerton, an Austen-adjacent series released on Netflix in December 2020. Based on Julia Quinn’s historical Regency romance The Duke and I (2000), the series was unusual in employing color-conscious casting, which necessitated its adapters’ inventing an alternative history of England to explain the centrality of Blacks in the highest levels of English society in the early nineteenth century (Regé-Jean Page portrayed the Duke and Golda Rosheuvel was Queen Charlotte).2 The series is as visually gorgeous as Emma. from earlier in the year, but it also consciously avoids the “heritage” feel typical of period drama. Highly stylized costumes in anachronistic fabrics and colors, over-the-top hairstyles for the Queen, and a score that combines both pop and period music gives Bridgerton a theatrical look that melds modern and Regency cultures. In the process, it opened a space for multiculturalism in period drama by loosening up artistic approaches for film.3

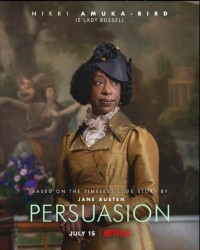

Two years later, Netflix tried this approach on a work by Jane Austen, but with less success. Persuasion (2022) garnered criticism among Austen fans mainly for its use of filming methods associated with edgy British comedy and its anachronistic interpretation of Anne Elliot, played by Dakota Johnson. It was aimed at a youthful audience (Zemler), not at Austen fandom, which accounts for the complaints from the latter about its flippant approach to Austen’s most romantic novel, but it was well liked by its target audience.

Two years later, Netflix tried this approach on a work by Jane Austen, but with less success. Persuasion (2022) garnered criticism among Austen fans mainly for its use of filming methods associated with edgy British comedy and its anachronistic interpretation of Anne Elliot, played by Dakota Johnson. It was aimed at a youthful audience (Zemler), not at Austen fandom, which accounts for the complaints from the latter about its flippant approach to Austen’s most romantic novel, but it was well liked by its target audience.

It also attracted comments, both positive and negative, for its use of colorblind casting. The film features a multiracial cast, including Nikki Amuka-Bird as Lady Russell and Henry Golding as Mr. Elliot, but unlike Bridgerton, racial issues were not interpolated into Austen’s story. Persuasion was directed by Carrie Cracknell of the National Theatre in London, where disregarding race when choosing actors for stage productions has been standard practice for decades. While some criticism about directorial choices was thoughtful and well-considered (colorblind casting is a “form of erasure of racism”4), other online comments were simply repellent.5

There will be more multiracial casting in classic adaptations and historical drama in coming years because of Netflix’s demonstrated commitment to turning an “inclusion lens” on its productions (Myers) and the U.K.’s House of Commons recommendation that public-service broadcasters ensure that screen arts more accurately reflect the current and future composition of the U.K. population (36–37). As stage productions have been doing for decades, Austen adaptations moving forward will certainly be reflecting the range of cultures and skin tones that now make up the U.S., Canada, England, and JASNA itself.

Updating Austen for a New World

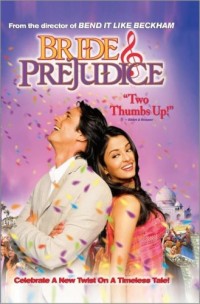

While multiracial casting of period adaptations of Austen has generated some criticism, reflecting the current makeup of a national population has proven less problematic in Austen updates, a genre whose roots can be traced to Amy Heckerling’s film Clueless (1995) and Helen Fielding’s novel Bridget Jones’s Diary (1996). Gurinder Chadha produced the Bollywood-style Bride and Prejudice in 2004, with Austen’s characters recast as from India, England, or the U.S., and it was the first film for the U.S./U.K. market to position multicultural diversity as a major element in the storyline.6 From Prada to Nada (2011) followed, which focused a Latina lens on Austen,7 and the Lifetime telefilm Pride & Prejudice: Atlanta (2019) repositioned Austen’s narrative in the Black community of Atlanta, Georgia.

Retellings of Austen, whether in films or novels, face certain challenges in creating story worlds that parallel Austen’s Regency world. For example, they need to present modern versions of “3 or 4 Families in a Country Village” (9–18 September 1814), the social class of the gentry, and the practice of entailment. They also need to account for the fact that society today is significantly different from Austen’s day: both men and women have more choices, and the population is more diverse and mobile.

And there is the matter of the story. Adapters reworking other British literary classics, such as Gulliver’s Travels, have an easier time of it since they are under less obligation to maintain principal plot episodes. Not so for the adapter of Jane Austen. Narrative features are central. For Pride and Prejudice adaptations, for example, certain story elements need to be imitated, for instance, the first assembly in Meryton, the disastrous proposal, the eye-opening visit to Pemberley, and the problem caused by Lydia and Wickham.

A recognizable configuration of central characters matters more. Novels that draw inspiration from Austen should be sensitive to the characters she created. The Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy equivalents should have personalities somewhat resembling their originals and, most important, their relationship should evolve in the same way: moving in clear stages from dislike for each other to love and respect. A story with the essential plot points and with characters exhibiting the specific relationship pattern is the essence of any Pride and Prejudice update. If those pieces are in place, writers can then transcend time, place, and culture to build a variety of stories that explore modern issues while working with Austen’s structure.

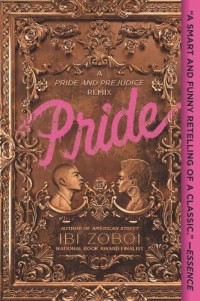

Pride

Ibi Zoboi’s young-adult novel Pride (2018) is the first U.S. multicultural novel to incorporate Austen’s structure and characters. It is less a romance than a story about family, love, heritage, coming of age, and learning to become one’s own person. Zoboi relocates the narrative to the mixed-race Bushwick area of Brooklyn, a village within a city, and transforms the principal characters into seniors in high school. Haitian Dominican Zuri Benitez attends the local public school, and her new neighbor, Darius, a wealthy African American boy, attends a private school in Manhattan. Of course, Zuri takes a dislike to him immediately.

The tight-knit neighborhood and her family have been Zuri’s anchor: “I need to be on my block,” Zuri tells the reader, “in my apartment, and in my bedroom with my sisters. I know my place. I know where I come from. I know where I belong” (236). The threat in Zuri’s world is a good equivalent to the entailment of Pride and Prejudice: the neighborhood is gentrifying, and the Benitez family fears they will be forced out of the rental they have lived in for years when the current owner of the property dies. Thanks to her evolving friendship with Darius, by the end of the novel, Zuri finds the confidence to spread her wings beyond the anchor of her neighborhood, family, and culture and apply to her dream college, Howard University, in distant Washington, D.C.

In this novel, as in other updates, advanced education is the gentry equivalent. It will be a rare Austen update that features a character who is not an honors student or who doesn’t have at least a bachelor’s degree.

Pride and Protest

Nikki Payne’s Pride and Protest (2022), a romance from Berkley-Penguin, also grounds Austen’s story in the culture and economic concerns of Black urban America. In fact, large urban settings replace Austen’s villages in nearly all the updates.

Liza B is an African American radio personality in southeast Washington, D.C., who clashes with Dorsey, a real-estate developer. Her family is colorful in every sense of the word, being the offspring of Beverly Bennett by various fathers. Liza’s sister Janae is a recovering-alcoholic widow and “almost Miss DC—the entire district—for three years straight” (5). Brother Maurice, the Mary Bennet equivalent but much more perceptive, plays consciously into various black male stereotypes. At times, he calls himself “a hardened criminal raised by the streets” (7)—which Liza points out means he did time for not paying parking tickets—and at other times, he adopts “a Nation of Islam look with none of the entanglements of having read any of the doctrine” (5). Youngest sister LeDeya is highly materialistic and anxious to meet rich men: “Momma says those people over there are loaded—I’m talkin’ Red Lobster rich” (6).

But there is serious enterprise and education in this family, so they still work as gentry equivalents. Liza has a bachelor’s degree in international studies and a master’s degree in women’s studies from Howard University, and Janae is a math and finance whiz with a particular specialty in exposing banking scams. Even teenaged LeDeya has initiative and drive, though it does also get her into considerable trouble.

Dorsey’s family, also highly educated, especially showcases American diversity. Dorsey and his sister, Gigi, both adopted by a wealthy family of philanthropists, “looked nothing alike. His sister’s skin was the rich mahogany of the soil of her native land, Kenya, while he had the umber complexion of his native Philippine Islands. Her hair was a spun-cotton cloud of tight brown coils, and his was a uniform curtain of bone-straight ebony strands that he kept shoulder-length. Sure, they didn’t look like siblings, but Gigi was his sister all the way down to their matching vintage Chucks and identical mannerisms” (15-16).

A photo of the family is described as looking like the “Colors of the World skin-tone crayons” (55). As Nikki Payne comments in the Acknowledgments, “I’m indebted to those who joined me on this journey—taken like I was by the vision of Jane Austen, in color” (385).

The Bennet Women

Many updates featuring characters of color reflect Pride and Prejudice’s strong sense of place and family. More than for Austen, though, these updates are often celebrations of a hometown and of family roots. The Bennet Women (2021) by Eden Appiah-Kubi uses another equivalent for village and family. This novel tells the stories of several undergraduates living in Bennet House at Longbourn University in New England. The university stands in for Austen’s country village, and the students are as varied as the Bennet sisters, though in a way that reflects current college populations at elite schools. EJ, the Elizabeth Bennet character, is a Black engineering major, and Jamie (Jane) is a trans woman studying theatre and French. Tessa (Charlotte) is a Filipina astronomy major, and Will Pak (Darcy), a newcomer to campus, is a famous teen film star who looks like an “Asian Christian Bale” (33).

Many updates featuring characters of color reflect Pride and Prejudice’s strong sense of place and family. More than for Austen, though, these updates are often celebrations of a hometown and of family roots. The Bennet Women (2021) by Eden Appiah-Kubi uses another equivalent for village and family. This novel tells the stories of several undergraduates living in Bennet House at Longbourn University in New England. The university stands in for Austen’s country village, and the students are as varied as the Bennet sisters, though in a way that reflects current college populations at elite schools. EJ, the Elizabeth Bennet character, is a Black engineering major, and Jamie (Jane) is a trans woman studying theatre and French. Tessa (Charlotte) is a Filipina astronomy major, and Will Pak (Darcy), a newcomer to campus, is a famous teen film star who looks like an “Asian Christian Bale” (33).

Though its cultural interests are far from those of Austen, the novel does center on the rocky romance between EJ and Will, but their relationship will have to accommodate other concerns. In the coming year, EJ will be attending the University of Edinburgh on a major fellowship to do environmental study, and Will plans to fight against stereotypical roles for Asians by starting his own production company. He also, however, wins a continuing role on Doctor Who, which will put him geographically near Scotland for part of the year.

Educational attainment (or aspiration thereto) again stands in for gentry status, but romance is not the main goal of these twenty-first-century students. A boyfriend or girlfriend is great, but more important is having a meaningful career that will allow each graduate to make the world a better, more inclusive place.

Debating Darcy

A different academic resituating of Pride and Prejudice appears in Sayantani DasGupta’s Debating Darcy (2022). This young-adult novel sets Austen’s story in the world of competitive high-school forensics. The competitions work especially well as stand-ins for Austen’s marriage-market-oriented activities, the balls and dances. The South Asian community of New Jersey works as the village here, and the teams function as families that supplement the students’ real families.

A different academic resituating of Pride and Prejudice appears in Sayantani DasGupta’s Debating Darcy (2022). This young-adult novel sets Austen’s story in the world of competitive high-school forensics. The competitions work especially well as stand-ins for Austen’s marriage-market-oriented activities, the balls and dances. The South Asian community of New Jersey works as the village here, and the teams function as families that supplement the students’ real families.

Leela Bose, of Bengali descent, is a student at Longbourn (public) High School and competes in the speech division. Firoze Darcy, of Pakistani descent, is a student at (private) Netherfield Academy and son of the president of Pemberley College. He competes in debate. As Leela tells the reader, “It is a truth universally acknowledged that there are two kinds of people in high school forensics: speakers and debaters” (11). Speakers value “interpersonal connection,” and debaters “are the mansplainers of the forensics world” (11). One sees the stage for conflict being set.

The initial meeting of the two at the first competition quickly sets up the Pride and Prejudice vibe.

I was on the . . . cafeteria table, in the middle of performing my favorite song from Hamilton with my friends Tomi and Jay, when I saw him. A boy I’d never seen before. He was suited and booted, as my cousins in India would say. . . . Also, I realized with a weird skip of my heartbeat, he was Desi. Like me. . . .

But while most of us looked like awkward adolescents wearing cheap, off-the-rack imitations of adulthood, this guy looked like somebody had cut and molded his dark blue blazer to his not-inconsiderable shoulders. . . .

So, logically, I entirely blame him for what I did next. Which was to look straight down into the boy’s dark eyes from my perch on the wobbly cafeteria table, crook my non-manicured finger at him, and start singing at him, like he was a beautiful woman and I the future murderous vice president of the United States: “Excuse me, miss, I know it’s not funny, but your perfume smells like your daddy’s got money.” The entire cafeteria, already hopped up on nervous competition energy and vending machine snacks, exploded in laughter. (2–3)

The novel finds good modern equivalents for a lively, teasing Lizzy and a deeply uncomfortable Darcy. One can see why he would be put off by her at first, but then charmed by her liveliness and confidence.

This very funny young-adult novel also includes serious material. The characters, like Austen’s, deal with snobbery, cliquishness, a terror of public humiliation, and a fear of being different, but the young women also have problems of the #metoo era. The female “forensicators” (11) must deal with sexism from the judges in the form of comments on their clothing and harassment from one of the male competitors. Jishnu Waddedar, the Wickham figure, of course, turns out to be the harasser.

Firoze Darcy will help resolve the situation, though DasGupta’s female characters do the bulk of the heroics, unlike in Austen. Firoze suggests that Lidia post her experiences on his sister Gigi’s Instagram site DebateStories, and the covert recording of Jishnu’s promising to fix Lidia’s scores in the judge’s room in exchange for sex proves especially compelling evidence and brings Jishnu down. Firoze also encourages Leela to take greater risks in her competitions, inspiring her to move from the category of speech, where she speaks the words of others, to debate and then original oratory, where she can create and present her own words and arguments.

What is especially notable in this update is that Firoze is a supporter, a helper, not a heroic rescuer. The women in this novel rescue themselves, and they speak for themselves. And while there is romance in the novel, most of the book is a battle of wits and words between the two students and the story of how Leela finds her true voice, an empowering message for young women to hear.

Pride and Prejudice and Other Flavors

DasGupta’s young-adult novel is part of the South Asian end of the genre. Austen connects strongly with those of such heritage (Malik), and the proliferation of updates set in South Asian communities of the U.S., Canada, and England or set in Pakistan and India has accounted for the majority of multicultural Austen material (see the bibliography at the end of this essay).

Sonali Dev’s Pride and Prejudice and Other Flavors (2019) is part of a quartet of Austen homages centered on one Indian family in California. Dr. Trisha Raje, an arrogant Stanford “skull-based neurosurgeon” (38) and daughter of a maharajah-turned-American-surgeon, takes an instant dislike to DJ Caine, a Cordon-Bleu-trained private chef of African and British heritage, who has come to California to be a caregiver to his sister. DJ returns Trish’s disdain, but she quickly becomes fascinated by him—or rather, by his stunning take on the Indian cuisine he prepares as caterer for brother Yash’s political fundraisers (he’s running for governor of California).

As Darcy and Lizzy characters must do, even when gender-reversed, they eventually resolve their differences, partly aided by a crisis: years ago, Trish’s brother Yash (positioned as the Lydia figure) was drugged, compromised, and videotaped by Julia Wickham, Trish’s college roommate. The Raje family paid her off, but she is back in town and out for revenge by taking advantage of one of Trish’s patients, DJ’s artist sister, whose has a brain tumor that is destroying her eyesight. Trish, in Darcy style, helps rescue them from Julia’s online fundraising scam by discovering a legal loophole. Also, Trish saves DJ’s sister’s life through surgery and her vocation by connecting her with other blind artists.

In addition to charting the transformation of Trish, the dramatic novel addresses through a large cast of characters several important motifs: sacrifice—to parents, of one’s dreams—and responsibility—to family, to one’s political constituents, to one’s work. As Austen’s do, Dev’s characters struggle to balance personal wishes and happiness with obligations to others. Family is treated with Austen’s equivocalness: it can be supporting but also strangling. Parents can be affectionate, but also indifferent or disappointed. Siblings can be supportive, but they can also undermine one’s life.

Sansei and Sensibility

Karen Tei Yamashita, in Sansei and Sensibility (2020), uses Austen’s structures and characters even more loosely than Dev does. This collection transforms each Austen novel (plus Lady Susan) into a comic short story featuring Japanese American families in California during the late 1960s.

Karen Tei Yamashita, in Sansei and Sensibility (2020), uses Austen’s structures and characters even more loosely than Dev does. This collection transforms each Austen novel (plus Lady Susan) into a comic short story featuring Japanese American families in California during the late 1960s.

“Giri & Gaman” is the Pride and Prejudice update in the volume, and it explores some of Austen’s comic characters even as it dispenses with her plot.8 Yamashita’s three or four families in a small California town have been in the United States for a few generations. Mr. Benihana makes and repairs prosthetic teeth and bridgework (skills learned in the camp and the U.S. Army) while listening to audiotaped Harvard Lectures on American philosophy; Mrs. Benihana is hyperactive in the PTA.

The protagonists are highly intelligent East Asian high school students with the same names as Austen’s younger characters, and their antagonist is Miss Catherine Borg, a condescending and insensitive Caucasian high-school principal who also writes unimaginative young-adult novels. She is aided by the fatuous school librarian, Mr. Collins, who secretly tapes the students to gather dialogue for the next novel. Needless to say, the students turn the tables on them.

The story is set in 1967, which allows Yamashita to show Japanese American parents shaped by the internments and their children shaped by pop culture and materialism. The story includes references to the latest technology (tape recorders), culture (Salinger, The Graduate), and trends (hippies, Mao jackets, pot-smoking). The period and the high-school setting put limits upon opportunities for the girls—except for Liddy. The narrator explains that she will eventually “hook up” with George Wakama, a backup singer for The PersuAsians, and “go rogue, so to speak,” disappearing into “an underground collective” where she will do “all the usual stuff like sex, drugs, and radical politics” (131). Most Austenian elements must be jettisoned in this very short story, but the final result is a zany piece of satire in the style of Austen’s juvenilia.

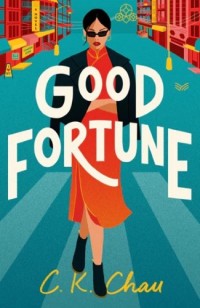

Good Fortune

Good Fortune (2023) takes the East Asian update further. C. K. Chau uses an urban setting, New York’s Chinatown, and a period setting, the year 2002, just after 9/11 but, more significantly, just after China has joined the World Trade Organization and is seeking investments in the United States.

The class lines in this update are wide. The immigrant Chen family with its five daughters perpetually struggles: they rent a shabby two-bedroom apartment, and they have no health insurance. Mr. Chen operates Lulu’s, a takeout restaurant owned by someone else, and Mrs. Chen aspires to a career in real estate. Her main goal in life, however, is to see her daughters achieve financial stability by getting good jobs and moving out. The older daughters have the expected educational attainments for gentry equivalents: Jane is in medical school, and Elizabeth is a college graduate with a degree in communications and photography, a bit of a disappointment to her mother, who had hoped she would major in something “profitable” (7). Elizabeth is finding it hard to land a full-time job, however, careers being the modern equivalent for Austen’s marriage market.

The highly comic plot concerns rich Hong Kong investors Darcy Wong and Brendan Lee, who have purchased the down-at-the-heel Greater Chinatown Neighborhood Youth Recreational Center, with plans to renovate, or, as Elizabeth puts it, “Destroy” Chinatown (4). Urban redevelopment has become a standard trope in Austen updates as a vehicle for generating conflict between the protagonists as it pits the outsider against the insider, those with money against those without.

There are clever equivalences for Pride and Prejudice in this novel: a Chinese wedding reception stands in for the Meryton Assembly, and Darcy’s insult to Elizabeth slights her education, not her appearance: “the last thing I want or need right now is some middle-of-the-road elevator pitch from a girl who’s drunk, single, and has nothing better to do at a wedding than to enlighten you with her state-school, intro-poli-sci ideas about how we should do our jobs” (37). Mary’s wretched singing is replaced with Mrs. Chen’s off-key karaoke performance. Rosings becomes a property-management company with a satellite office in Scranton, Pennsylvania, where Charlotte gets the job Mrs. Chen thought should have gone to Elizabeth. Pemberley is a combination historic property and community resource for lower-income youth in Boston. Lydia’s crisis revolves around signing a modeling contract, participating in a “very adult photo shoot” (355), and disappearing with Wickham. (As this novel is set in 2002, Darcy can save the situation by reclaiming physical pictures and film negatives to save the Chen family from humiliation.)

The shifting relationship between Elizabeth and Darcy remains central, however, and lines and moments from the novel are wittily reworked even as the novel addresses the worries of the working-class immigrant: how to assimilate, how to keep hold of one’s heritage, how to survive financially, and how to achieve the American dream for one’s children.

![]()

While these updates build upon Pride and Prejudice’s plot, characters, and concerns, they also differ from Austen stylistically. None employs her spare descriptions of character and dress. Readers will find the updates highly descriptive and rich in sensory appeal. Heritage film adaptations have encouraged a greater emphasis upon the visual, but so has the nature of modern life.

Austen updates situated within well-defined diverse American communities need to give us a full-color portrait of their worlds, not just a pencil sketch, and that portrait will include descriptions of dress, décor, and food as well as customs, celebrations, and language. Such a fully presented mis-en-scene gives readers who are members of the culture the joy of recognition and allows them to see themselves in stories like Austen’s. They also help outsiders to the culture visualize that world and become, for a time, insiders. Some authors even offer a literal taste of the culture by sharing recipes. Just as modern Austen readers are pulled into Austen’s nineteenth-century world, readers of these updates will find themselves immersed in the experiences of a multicultural U.S. And these novels do not need to rewrite history, as Netflix’s Bridgerton did, to justify their casting choices.

What consistently remains from Austen, besides the core plot elements and character relationships, is the emotional side of the reading experience. Humor derived from the tensions of family life pervades the updates. Satire based upon perceptions of differences in social status arises repeatedly and in enlightening ways. In these well-crafted stories, again and again we empathize with the central characters as they reject each other, attract each other, and end up entangled with each other beyond their expectations, though not beyond ours. Austen has become a bridge to unite diverse communities, with narratives that appeal to both those who have yet to read one of her novels and those who know her work intimately.

NOTES

1Kumar discusses “some of the approaches taken with regard to race when adapting Austen” and considers possible directions for future adaptations—directions that have indeed been taken.

2There is faint inspiration for regarding Queen Charlotte as having some African ancestry, though it would have dated back centuries (Jeffries).

3Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton (2015) should be credited with bringing attention to alternative ways of casting actors in historical material.

4See, for example, Brandon’s critical but perceptive review in his blog Sweater Weather and responses in the comments sections from Lilith (7 August 2022) and Rahma (19 September 2022).

5See, for examples, the negative comments screen-shotted in Prescott’s “Persuasion Discourse.” Hernandez-Knight, Prescott, and Sinanan have all written thoughtfully and directly on episodes of intolerance within the Austen community.

6In addition to the English-language film of Bride and Prejudice, there have been several successful Hindi and Tamil film adaptations of Austen. See discussions by García-Periago, Kasbekar, Kenney, and Troost and Greenfield.

7Villaseñor notes that Latinas, not Austen readers, were the target audience for this adaptation.

8The title can be roughly translated from Japanese as “sense of duty, obligation and patience, endurance, grit.”