Pictures of perfection . . . make me sick & wicked”: so Jane Austen confesses in a letter to her niece Fanny Knight, in a discussion about differing “ideas of Novels & Heroines” (23–25 March 1817). Given the many delights Austen’s satire offers to readers, we may all be grateful that she so preferred pictures of imperfection; nevertheless, the fact that clergymen were not exempt from her aversion to idealized portraits has caused discomfort to some of Austen’s readers, including close members of her own family. For instance, in his 1871 Memoir, her nephew the Rev. James Edward Austen-Leigh feels a need to defend his aunt’s fictional clergy: “No one in these days,” he acknowledges with pained pride, “can think that either Edmund Bertram or Henry Tilney had adequate ideas of the duties of a parish minister.” Yet such “were the opinions and practice then prevalent among respectable and conscientious clergymen.” To Austen-Leigh’s way of thinking, Edmund and Henry are “like photographs”: accurate depictions of men who, though imperfect, nonetheless served respectably in a profession Austen held in honor. They are, in other words, “faithful likeness[es]” of faithful men (116). This view is shared by many today, such as Brenda S. Cox, who notes that “Austen’s novels show good and bad clergymen, but even her bad clergymen do their jobs,” and holds that “while some [of Austen’s] clergymen were focused on material gain, most had better motives” (133). Irene Collins similarly notes that Mr. Collins deserves credit for not shirking his duty; he is, rather, “the type of man who carried out his obligations to the letter” (94). I do not disagree.

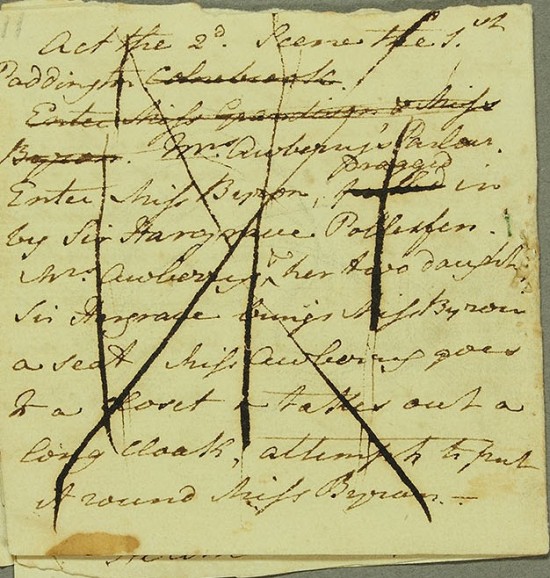

I do, however, wish to complicate our understanding of Austen’s aims and her development as a satirist of the clergy by looking closely at the rocky road the young author travelled on her way to Edmund and Henry: a journey that began as early as 1792 when, at age sixteen, she set out to represent a priest in “Sir Charles Grandison,” a dramatic adaptation of her favorite novel.1 In brief, she completed act 1, made two false starts on act 2, scene 1—the scene that contains a most unsavoury priest—and then quit writing (Fig. 1). Some eight years later she completed the play, priest and all, but this happened only after she took a significant detour in 1796–1797 to write “First Impressions.” This story, of course, she in time turned into Pride and Prejudice (1813), which features Mr. Collins, that blockhead of a priest whom so many of us love to loathe—and to laugh at. This eight-year interruption to the work on “Sir Charles Grandison” is intriguing, and a number of reasons have been suggested. Marilyn Butler, for one, reads the two cancelled openings to act 2 as evidence of an “inexperienced adapter” who quit simply because she could not determine how to proceed. I have argued elsewhere that Austen stopped writing in 1792 not because she lacked the technical skill to continue but because she lacked the resources necessary to proceed. Act 1 can be staged with only five actors and does not require a curtain; act 2 requires seven actors, act 5 requires thirteen, and acts 2 through 5 also require a stage with a curtain. It does seem clear that Austen was, in 1792, facing “the kind of technical problem that only different actors” or “a different stage . . . could solve” (Peterson, Introduction xxxi).

Figure 1. Sir Charles Grandison or the Happy Man. A Comedy, by Jane Austen. Act 2, scene 1, cancelled (p. 11 in the second group of manuscript pages). Courtesy of Chawton House.

In this paper, however, I build on my earlier suggestion that “young Jane Austen may well have been discouraged or even forbidden” from completing the play in 1792 (Introduction xxxi). The priest in her “Sir Charles Grandison” is no such “faithful likeness” as we find in Edmund or Henry but a caricature closely based on Richardson’s original. Austen’s version is less grotesque than Richardson’s “snuffling monster” (155) and more materialistic, but he remains completely recognizable as the vile clergyman who, in one of Richardson’s best-known passages,2 assists the villainous Sir Hargrave Pollexfen in his (ultimately failed) plot to force into marriage the heroine, Harriet Byron, whom Sir Hargrave has abducted. Accordingly, in this essay I read Mr. Collins for traces of Richardson’s unpalatable priest as well as for traces of Austen’s grappling with familial and cultural restrictions on the representation of the clergy.

Mr. Collins’s creator grew up in a family and community of priests.3 She also grew up in a family that delighted in putting on plays, mainly satirical, but that avoided staging any play with a priest in its dramatis personae. This restraint may be accounted for, at least in part, by the influence of Jeremy Collier, self-appointed scourge of the Restoration stage, whose vituperative pamphlet A Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage (1698) led to a pamphlet war that endured for decades.4 A priest ordained in the Church of England, Collier devotes an entire, long chapter of his Short View, titled “The Clergy Abused by the Stage,” to itemizing his many grievances against the representations of priests in the Restoration theatre. Collier’s Short View cast a long shadow over the eighteenth-century theatre—a shadow that appears to have extended as far as Steventon. The story I am telling here, then, is one of Jane Austen’s emergence from that shadow into the “light & bright & sparkling” world of Pride and Prejudice (4 February 1813). Ultimately, if Collier’s prohibitions, as taken up by her oldest brother and theatrical mentor, James Austen, first prevented Jane Austen from writing the scene she had in mind, they also helped to shape the writing she finally produced, for both her adaptation of Richardson’s priest and her own original, Mr. Collins, show evidence of Collier’s influence—which, if she first deferred to, she later found ways to laugh at.

Even though she did not immediately realize her ambition to transpose Richardson’s nasty piece of clerical work from page to stage, the mere fact that sixteen-year-old Jane Austen set out to do so appears remarkable when we consider that not one of the plays the Austen family is known to have performed between 1782 and 1789 features a clergyman—not even an admirable one. Though possibly a coincidence,5 this consistent omission is more likely an instance of self-censorship on the part of James Austen: the driving force behind the family theatricals, he was also headed for a career in the church, and the prologues and epilogues he wrote for the family theatricals he spearheaded regularly express James’s anxiety about how best to reconcile his theatrical taste with his professional goals. For instance, his prologue to Thomas Francklin’s Tragedy of Matilda, the first play the Austen family staged (in 1782), justifies the choice of this maudlin verse drama in terms of Aristotelian propriety: the verse in Matilda is more important than the spectacle, without which proper balance a play cannot achieve the Aristotle-approved goal of “instruct[ing] & pleas[ing]” its “audience” (James Austen 9, l. 29; see also Peterson, “Things” 81–87).

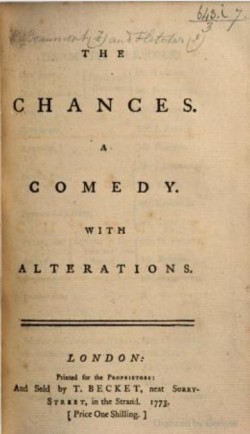

By the time he writes his prologue to Susannah Centlivre’s play The Wonder! A Woman Keeps a Secret, staged at Steventon in December 1787, James has taken a different tack: whereas the Puritans had banished the Church of England, the theatre, and the celebration of Christmas along with the monarchy, all of these had returned to England at the Restoration in a package deal of goodness consisting of “Charles, & loyalty, & wit” (James Austen 19, l. 40). It therefore follows that celebrating the Christmas season by staging witty plays like Centlivre’s is an act of good, old-fashioned Tory piety to be proud of (Peterson, “Things” 90–91). This is so, apparently, despite the fact that The Wonder! has some highly suggestive moments, and the play chosen for January 1788 has even more. Originally written in 1617 by two contemporaries of Shakespeare, Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, The Chances was significantly revised by George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham in 1682 and revised again by David Garrick in 1754. As Elizabeth Inchbald remarks, “That Garrick, to the delicacy of improved taste, was compelled to sacrifice much of [Beaumont, Fletcher, and Buckingham’s] libertine dialogue, may be well suspected, by the remainder which he spared” (2). In this performance, Garrick’s efforts notwithstanding, members of the Austen family or their circle would have been called upon to perform the roles of a rake, a bawd, an almost-whore, and an unwed mother.6 Still, there is no priest in The Chances—perhaps this latter fact is what made the play an eligible choice in the eyes of James Austen, who was ordained and given his first curacy later that same year. Respecting Collier’s prohibition against clergymen allowed the Austens, always so appreciative of wit and satire, to stay on the right side of English theatrical history.

When it comes to priests, Collier’s principles leave little room for even the gentlest of mockery. In his detailed catalogue of all the instances he can find of plays that profane the stage by “entertain[ing] the Audience with Priests” (123), Collier cites one instance of a play featuring a priest who acts as a pimp and another one whose protagonist “says the churchman is the greatest atheist” (100).7 Collier is incensed not only by such noteworthy crimes as these; he is also outraged by clergymen who speak “nonsense” of any kind (109). Worse are those who “play the Fool . . . Pontificalibus [in vestments],” and worst of all those who behave in a “servile and submissive” way to “Persons of Quality” (139). On these grounds alone, Collier would by no means have approved of Mr. William Collins.

Collier also completely rejects the standard argument that satire targets only individuals, not the profession:

Well! but the Clergy mismanage sometimes, and they must be told of their Faults. What then? Are the Poets their Ordinaries? 8 Is the Pulpit under the Discipline of the Stage? And are those fit to correct the Church, that are not fit to come into it? . . . The Clergy may have their Failings sometimes like others, but what then? The Character [i.e., role performed] is still untarnish’d. The Men may be Little, but the Priests are not so. And therefore like other People, they ought to be treated by their best Distinction. (138)

The “Poets” (i.e., playwrights) have no right, Collier insists, “to correct the Church” or to judge an individual clergyman’s “Failings.” (On the contrary, they have a positive responsibility to show respect for the office, to treat priests at all times “by their best Distinction.”) Novelists could generally get away with such behaviour; Richardson did, and in time so did Austen. But on stage, in the eighteenth century, things were different.

Figure 2. Title page of The Chances, by Francis Beaumont, John Fletcher, and George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, ed. David Garrick (1773).

There is some debate among historians of the English stage as to whether Collier’s work effected or merely reflected the marked change in taste that occurred at the turn of the century, when the bawdy wit of Restoration comedy began to give way to the sentimental comedy that would dominate the eighteenth-century stage. Regardless, the pamphlet was well known and frequently reprinted, and James Austen’s habit of reflection on the vexed matter of plays and propriety makes it highly unlikely that this young impresario would have been unaware of, or unmoved by, Collier’s arguments. In fact, none of the Austens involved in the theatrical activities of the 1787–88 holiday season could have avoided reflecting on the change in taste between the Restoration era and their own or on the acts of censorship this change necessitated, because this history is documented on the title page of The Chances, which includes the subtitle “With Alterations” (Fig. 2). Furthermore, it is further addressed in the “Advertisement” that follows: “The Duke of Buckingham . . . certainly added interest, and spirit, to the fable and dialogue; but the play, when it came out of his hands, was still more indecent than before” (vii). It was therefore necessary for Garrick to tone things down; the editors of his version confidently hope that “this play [will] be thought, in its present state, a more decent entertainment” (viii).

We may, then, despite its risqué content, read the Austens’ choice of The Chances as an endorsement of the sort of corrections of the stage’s “immorality and profaneness” that men like Collier called for. Since James Austen’s prologues and epilogues, especially the early ones, clearly signal a principled reluctance to approve just any script indiscriminately, this stance must have been well understood by his youngest sister. According to Austen-Leigh, James had “a large share in directing Jane Austen’s reading and forming her taste” (16), and although Austen-Leigh’s Memoir cannot always be taken on face value, considerable evidence supports this particular assertion where drama is concerned.9 For instance, Jane Austen dedicates her short play “The Visit” to James, whom she addresses as “the Revd James Austen” and calls “so respectable a Curate” (J 61). “The Visit” (which conforms to family norms in containing no priest) was probably written as an afterpiece, to be performed immediately following James Townley’s farce High Life Below Stairs as part of the family theatricals of December 1788 (Byrne 13–14).10 Together, “The Visit” and its dedication show us an aspiring playwright who wants to acknowledge her brother’s mentorship. She has been paying attention to the plays James has chosen, to the paratexts he has created to accompany them, and, I believe, to the serious issues about theatrical propriety that they raise. It is hardly surprising that this daughter and sister of clergymen may have needed time and space before she could break with such a prohibition as Collier’s, especially if it were one that her own big brother had long obeyed and endorsed.

Austen was in her early twenties before she completed the scene with the clergyman in act 2 and then proceeded to complete the play “Sir Charles Grandison.” Her prose juvenilia do contain clergymen, but these are sketchy figures, and they are few. In “The Generous Curate, a Moral Tale” (1793), an unnamed curate adopts one of the two sons of a neighbouring “Clergyman,” with “the intention of educating him at his own expence” (J 94). Unfortunately, this curate (in a humorous reversal of the adoption by a wealthy family that Jane’s brother Edward experienced) earns significantly less than the boy’s own father and so cannot afford to educate him properly; consequently, the young man learns almost nothing, and his “genius” is “cramped” (J 94). We approach just a little closer to Richardson’s disreputable priest in the epistolary novel “Love and Freindship” (1790), when Laura tells how she and her “Dear and Amiable Edward” were, on the “perfectly Dark” December night of their first meeting, “united by my Father, who tho’ he had never taken orders had been bred to the church” (J 109). Whereas the curate of Austen’s short tale fails to follow through on his intended generosity, this man apparently failed to follow through on ordination—but that does not stop him from conducting a marriage ceremony. We have no definitive evidence one way or another of the qualifications of Richardson’s priest, though Sir Hargrave addresses him as “Doctor” (e.g., 156), which suggests positive knowledge of his educational background.11 Nevertheless, Richardson has Harriet raise doubts on the subject when she wonders parenthetically “if a minister he was” (155). In any case, weddings were traditionally conducted during the day before noon, so the timing alone of this ceremony renders it suspect, just as the timing of Laura’s marriage in “Love and Freindship” underscores its shortcomings.

There are legal marriages in the juvenilia, but, unlike what we find in the mature novels, no heroines of Austen’s teenage novels marry clergymen.12 In fact, in the juvenilia, clergymen are most prominent in the dedications: “The Visit” is dedicated to James Austen, as we have seen, and “The Mystery: an unfinished Comedy,” to Austen’s father, “the Revd George Austen” (J 69). In neither play’s dramatis personae can a clergyman be found; nor is there one in the “First Act of a Comedy.”13 Such an omission, in Collier’s terms, signified virtue and propriety; perhaps Jane Austen’s father and brother were expected to take note of this omission in her dramatic works and approve.

Nevertheless, clergymen were too big a part of Jane Austen’s lived and literary worlds for her to neglect them forever, and no self-respecting novelist could live by Collier’s rules. Nor did Austen wish to. Shortly after the publication of Pride and Prejudice, she succinctly described the clergyman she would never write, as part of the novel she would never write, in her “Plan of a Novel, according to hints from various quarters” (1816): this paragon of virtue and propriety is a retired curate, the “most excellent Man that can be imagined, perfect in Character, Temper, & Manners— without the smallest drawback or peculiarity” (Later Manuscripts 226). Biographers note Austen’s recent encounter with James Stanier Clark, the Prince Regent’s Librarian, as the obvious primary inspiration for this “Plan”; others among the “various quarters” she took her hints from include “the popular fictional forms of the 1810s” (Mandal 181) and such earlier novels as Fanny Burney’s Evelina (1778). But perhaps some of the hints Austen gestures to here came not from books but from close quarters. In 1800, she was still sharing quarters with her father, George Austen, though not with James, who had become curate of nearby Overton and moved there in 1790 (Le Faye 71). She was also a regular visitor to Godmersham Park, where clergymen did visit but did not live or set the rules. By 1816, George Austen was only a memory, James had taken over Steventon Rectory, and Jane, along with her mother and sister Cassandra, was in Chawton.

Richardson’s clergyman would hardly have been a welcome visitor in any home Jane Austen spent time in, simply because of his appearance and his manners, which are both calculated to nauseate. Harriet Byron describes the man who shows up intending to marry her to her abductor as “the most horrible-looking clergyman that I ever beheld. . . . A vast tall, big-boned, splay-footed man. A shabby gown; as shabby a wig; an huge red pimply face; and a nose that hid half of it, when he look’d on one side, and he seldom look’d fore-right when I saw him.” The “shabby gown” and wig suggest poverty, which might make us sympathetic were it not for the face and nose. These rather suggest some combination of poor hygiene, disease, and alcohol addiction. The nastiness is not even skin-deep: “The man snuffled his answer thro’ his nose,” writes Harriet, explaining that “[w]hen he opened his pouched mouth, the tobacco hung about his great yellow teeth” (154). As if this were not enough, the failure to look “fore-right” signals a shifty character.

Partly because of the difference in genre, it is hard to say exactly how Austen intended the Clergyman in her version of “Sir Charles Grandison” to appear on stage. She provides no instructions on what the actor should look like in her dramatis personae, scene description, or stage directions, and Harriet makes no mention of the Clergyman’s appearance in her dialogue. It is possible that Austen simply referred her actor to Richardson’s novel and asked him to do his best to approximate the prescribed look with the available resources. It seems unlikely, however, that either Steventon or Godmersham Park could have provided the combination of actor, costume, and props required to achieve the grotesque look Richardson’s text calls for. Given the evidence of ongoing censorship in the 1800 manuscript, discussed in more detail below, it is also possible that Austen was discouraged from rendering her Clergyman too grotesque—or too common. The “tall, big-boned, splay-footed” form of Richardson’s priest is not in itself repulsive, but within the world of Sir Charles Grandison such size, combined with such lack of elegance, marks him as one fitter for the plow than the pulpit. Collier insists that “the Priest-hood is the profession of a Gentleman” (136); Richardson insists just as forcefully that this individual priest is anything but. Austen allows her Clergyman his status: in her play, as the passage quoted below illustrates, Sir Hargrave regularly addresses the Clergyman as “Sir.” Richardson’s Sir Hargrave never does this.

Yet in some ways, Austen’s more materialistic Clergyman is less dignified (and more comical) than Richardson’s original, who never allows himself to make an explicit expression of interest in money, despite the poverty that his shabby attire announces. When Richardson’s Harriet promises that she “will reward” him if she helps her, he replies, “I am above bribes, madam” (154–55). To be sure, this moment of dignity is heavily undercut on the priest’s departure: after Harriet has become injured in an escape attempt and collapsed, forcing Sir Hargrave to delay the ceremony, her abductor sends “away the parson” and the witness but first gives “them money,” with the curt instructions, “Take this” (161). It is a crass transaction revealing that money has been promised beforehand and that the two men have appeared in expectation of payment. Nevertheless, we are left in some doubt about the Clergyman’s corruptibility, since he turns down Harriet’s offer of payment without even inquiring how much it might be.

Austen’s Clergyman is at least one degree wealthier than Richardson’s, for he arrives with “his Clerk” (2.1, p. 8). This man is either his parish clerk, which would mean that the Clergyman has a benefice already and, with it, a steady income, however small, or else he is an assistant the Clergyman has hired for the occasion.14 Either way, the clerk’s presence tells us that the priest is here to supplement his income, not to avoid starvation. Even so, he does not hesitate to demand money:

Clergyman: —reads). Dearly beloved—

Miss Byron dashes the book out of his hand.

Clergyman: picking it up again). Oh! my poor book!

Sir Hargrave. Begin again, Sir if you please. You shall be well paid for your trouble.

Clergyman—reading again). Dearly Beloved —

Miss Byron snatches the book out of his hand & flings it into the fire, exclaiming,

[Miss Byron]. Burn, burn, quick.—

The Clergyman—runs to the fire & cries out.

[Clergyman]. O! Sir Hargrave, you must buy me another.—

Sir Hargrave. I will Sir, & twenty more if you will do the business.—Is the book burnt?—

Mrs. Awberry. Yes Sir—and we cannot lend you one in its place . . .

Sir Hargrave. Well Sir, I believe we must put it off for the present. . . .

Clergyman. Then I may go Sir I suppose. Remember the Prayer book.— (2.1, pp. 10–11)

Though unmoved by all Harriet’s many screams, faints, and exclamations, the Clergyman is full of solicitude for his “poor book!” when she “dashes” it “out of his hand.” This dramatic—even melodramatic—moment is original to Austen, which Juliet McMaster illustrated for the Juvenilia Press edition in 2022 (Fig. 3). But there is also comedy in the Clergyman’s concern for his prayerbook: Sir Hargrave must promise him money for it just to get him back on task. Then, after Harriet “flings it into the fire,” all he can think about is the cost of its replacement. Sir Hargrave simply “must” buy him “another.”

Figure 3. "Burn, quick, quick!" by Juliet McMaster. © Juvenilia Press, used with permission.

A lot happens in this scene, but Austen originally planned for even more, with a subsequently cancelled line that combines her own original detail of the fire with a moment from Richardson’s novel. In Richardson, Harriet Byron rejects the very language of the liturgy:

Dearly beloved, again snuffled the wretch. . . .

I stamp’d, and threw myself to the length of my arm, as he held my hand. No dearly beloved’s, said I. (Richardson, Sir Charles Grandison 155)

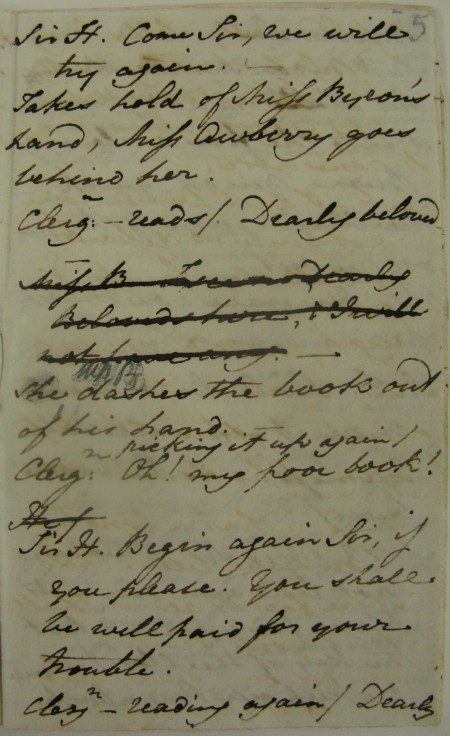

At first, as it appears, Austen wanted to expand on Harriet’s line, but then she (or someone else—there are multiple hands at work in the manuscript) cut it completely:

Clergn:— reads). Dearly beloved —

Miss B. I see no Dearly Beloveds here, & I will not have any.—

SheMiss Byron dashes the book out of his hand.

Clergn: picking it up again) Oh! My poor book! (2.1 [Diplomatic Edition], p. 34)

Harriet’s act of violence against the material object of the book survives the censor’s critical eye, but her rejection of the words the book contains—her rejection of the Word, we might say—is disallowed (Fig. 4). This cannot be explained in terms either of dramatic effect or faithfulness to the original; perhaps it is best explained in terms of a lingering concern within the Austen family with what may, and what may not, be shown on stage of priests and their office. Austen appears now to be quite comfortable satirizing priests as individuals, especially if the target of this satire is materialism or greed; but satirizing the priestly office, as represented here by the opening words of “The Form of Solemnization of Matrimony” in the Book of Common Prayer, remains off limits.

Figure 4. Sir Charles Grandison or the Happy Man. A Comedy, by Jane Austen. Act 2, scene 1 (p. 5 in the third group of manuscript pages).

Courtesy of Chawton House.

In choosing to focus on her Clergyman’s materialism, Austen may well have had in mind the fact that—as his detractors were fond of pointing out—Collier quite approves of theatrical depictions of priests enjoying wealth, its trappings, and secular power. Repeatedly, Collier shows himself willing to excuse other failings if the clergyman in a play behaves with dignity and is shown honor by others. Collier can even forgive Shakespeare (whom he believes wrongly to be the author) for a character named “John Parson of Wrothan (in the History of Sr. John Oldcastle).” By Collier’s own admission this Parson “swears, games, wenches, pads, tilts, and drinks: This is extremely bad”; yet Collier finds “some Advantage in [Sir John Oldcastle’s] Character. He appears Loyal and Stout [i.e., brave].” Moreover, “he is rewarded by the King, and the Judge uses him Civilly and with Respect. In short, He is represented Lewd, but not Little” (125). This priestly character is therefore, in Collier’s estimation, allowable on stage.

Elsewhere in his chapter on clergy, Collier does, as I mention above, rail against playwrights who represent priests as pimps or atheists, but the exception he makes for John Parson of Wrotham and others like him reveals that he considers these crimes to be minor failings compared to self-abasement. The Clergyman in Austen’s “Sir Charles Grandison” resembles a pimp in that he agrees to take money for delivering a young woman into the hands of a man who is determined to have her; in this he is as “Lewd” as Richardson’s original. But, like a true student of Collier, Austen makes him much less “Little,” significantly toning down the servility we find in Richardson’s original. For instance, Richardson’s parson insists to Harriet that her abductor is a “very hon-our-able man! bowing, like a sycophant, to Sir Hargrave” (154). By contrast, Austen’s Clergyman makes no attempt to flatter Sir Hargrave or to defend him. Rather, Sir Hargrave addresses him as “Sir,” as we have seen. Though she does not grant him dignity, Austen grants him status that Richardson does not, and she does not make him a sycophant.

Yet in this important quality, Mr. Collins is just like Richardson’s clergyman: t>he defining characteristic of each man is a willingness not only to oblige but to flatter the aristocrat who holds his meal ticket. We laugh along with Mr. Bennet on reading Mr. Collins’s boast: “‘I have been so fortunate as to be distinguished by the patronage of the Right Honourable Lady Catherine de Bourgh, widow of Sir Lewis de Bourgh, whose bounty and beneficence has preferred me to the valuable rectory of this parish, where it shall be my earnest endeavour to demean myself with grateful respect towards her Ladyship’” (70). We squirm in sympathy with Charlotte at Mr. Collins’s assertion that Lady Catherine “‘is the sort of woman whom one cannot regard with too much deference’” (179). Who among us can even think of Mr. Collins without thinking of his persistent veneration of Lady Catherine de Bourgh, and his corresponding self-abasement?

We do so with amusement, yet these are also the passages in which we encounter what makes Collier most angry of all: the “servile and submissive” priest “Belonging to Persons of Quality” (139). Seen in this light, Mr. Collins’s constant sycophancy appears much more serious a failing (in his character and in the character of his creator) than it might otherwise. We can acquit him of either bawdry or atheism, but in Collier’s terms that hardly even matters, because Austen has committed the most serious offense of all in depicting such excruciating “deference” in a priest.

Furthermore, in Mr. Collins Jane Austen repeatedly breaks Collier’s two cardinal rules for representing priests: “First He must not be ill used by others: Nor Secondly be made to Play the Fool Himself´(98). Mr. Collins thinks himself ill-used when Elizabeth rejects his proposal: “his pride was hurt,” and he believed “her deserving her mother’s reproach” (125–26). He is ill-used indeed when Lydia rudely interrupts his reading from Fordyce’s Sermons (76–77). The reader is also treated to many instances of others’ mockery or disrespect to which Mr. Collins is not privy, from Elizabeth and Mr. Bennet’s first discussion about whether Mr. Collins can “‘be a sensible man’” (71), to the narrator’s report that when Mr. Collins “said any thing of which his wife might reasonably be ashamed,” it “certainly was not unseldom” (177).

Still, for the most part, Austen makes Mr. Collins “Play the Fool Himself”; most of the sensible people around him, most of the time, treat him with respectful courtesy. It is the hallmark of his wife Charlotte’s management style. Even Mr. Darcy can respond politely to Mr. Collins’s presumptuous introduction of himself at the Netherfield Ball, which he justifies by insisting that “‘the clerical office’” is “‘equal in point of dignity with the highest rank in the kingdom—provided that a proper humility of behaviour is at the same time maintained’” (109). (Elizabeth, however, can read the signs of Darcy’s “astonishment” [109]). Whether we laugh at Mr. Collins or pity him in such a moment, and Austen in her empathy invites both, the fact remains that Austen repeatedly invites us to witness Mr. Collins’s weakness, and in Collier’s terms this should not be. Austen is flouting both of Collier’s prime directives, and insofar as Mr. Collins’s foolishness consists primarily of servile sycophancy, she is doing so in the worst possible way.

At the same time, insofar as Mr. Collins’s foolishness also consists of pride in his own status—consistently combining the show of “humility” with that of “dignity”—Austen is doing something quite new. To Collier, “playing the fool” consists primarily of being servile, whereas the priest who stands on his dignity covers a multitude of failings. To Austen, however, with her sharp eye for hypocrisy, this insistence on one’s dignity can be just one failing the more; we see this in her version of Harriet’s Clergyman and in her very original creation Mr. Collins as well. While Jane Austen shows respect for Collier by emphasizing the materialism of the Clergyman in her version of “Sir Charles Grandison,” in doing this she calls Collier’s values into question. After all, the grasping bully we meet in Austen’s play is hardly the admirable figure Collier has in mind when he argues, in language that would not sound out of place in the mouth of Mr. Collins, that the priestly role “has been in Possession of Esteem in all Ages, and Countries,” and that priests deserve “their Privilege” because “of their Relation to the Deity” and because of “the Importance of their Office” (127, original italics).

Elsewhere, Collier insists, “Ever since the first Conversion of Princes, the Priest-hood has had no small share of Temporal Advantage” (134). He is sure that this is how it should be. But not all his readers are convinced. As John Vanbrugh (one of the playwrights Collier attacks) protests, “He is of Opinion, That Riches and Plenty, Title, State and Dominion, give a Majesty to Precept and cry Place for it wherever it comes; That Christ and his Apostles took the thing by the wrong Handle” (30–31). William Congreve (another playwright Collier attacks) expresses a like outrage: “He now talks of nothing but great Families, great Places, wealthy and honourable Marriages, fine Cloaths, and in short, of all the Pomps and Vanities of this wicked World” (68–69). It is doubtful that Austen read Vanbrugh’s or Congreve’s responses, but any sharp-eyed reader of Collier might have made the same observations, and such a sharp-eyed reader as Jane Austen, who could spot hypocrisy a mile off, might well be tempted to satirize Collier’s.

To anyone familiar with Pride and Prejudice, the man who “talks of nothing but great Families, [and] great Places” is not Collier but Mr. Collins—whose wonderful “‘mixture of servility and self-importance’” makes him Collier’s fictional nemesis and avatar combined (71). Austen is not just breathing life into Collier’s worst nightmare; she is also breathing life into the worst nightmare of Collier’s enemies. Seen in this light, Mr. Collins remains relatively harmless, a man to laugh at as Mr. Bennet does rather than a man to fear, as Harriet fears the priest who tries to marry her to Sir Hargrave. But he is also the personification of everything that Collier most inveighed against, and, consequently, the expression of Jane Austen’s defiant rejection of Collier’s prime directives. We might say that, in the end, Jane Austen decided that Collier’s pictures of proud priestly perfection made her feel “sick and wicked.”

When James Austen-Leigh set out to defend the “opinions and practice . . . prevalent among respectable and conscientious clergymen” of his father’s generation (116), he was not only expressing his own late-Victorian values but also conveying an anxiety that his father had felt before him. That his late-eighteenth-century contemporaries would see him as “respectable and conscientious” is not something that James Austen took for granted, especially where his love for drama was concerned. James appears, moreover, to have communicated this anxiety—and with it knowledge about some of its sources, such as Collier’s Short View—to his younger sister Jane. As a consequence, for ten years or more the aspiring playwright and novelist wrestled with Collier’s prohibitions against making priests look foolish. During this time, she worked out how she might acceptably adapt Richardson’s “vile wretch” of a priest to the stage (154), a problem she ran up against hard in 1792 and did not solve until 1800. By this point, she had already completed the first draft of her most sustained priestly satire yet, featuring Mr. Collins. Both men of the cloth—the callous and greedy Clergyman who terrifies Harriet Byron and the self-satisfied blockhead who irritates and amuses Elizabeth Bennet—may be cut from the same pattern.

No manuscript of “First Impressions” survives, and we cannot know how fully Mr. Collins’s character was developed in that early version. It is possible, even likely, that Austen’s work on “First Impressions” helped her develop some of the strategies she would use a few years later when she found a way to adapt Richardson’s clergyman to the stage; it is equally possible that her work on “Sir Charles Grandison” helped her develop some of the strategies she would use a few years later when she revised “First Impressions” into Pride and Prejudice. Nor are the two possibilities mutually exclusive.15 In any case, both clergymen Austen created during this period show Austen alternately negotiating with and resisting Collier’s position—they also show her recognizing and resisting his pompous personality. In overcoming whatever forces blocked her from completing “Sir Charles Grandison,” she rejected Collier’s prohibition against putting undignified clergymen on stage, while softening the most offensive edges of Richardson’s original; here we can see her developing one strategy for navigating the competing demands of propriety on the one hand and artistic integrity on the other. In her creation of Mr. Collins, Jane Austen brilliantly combined what Collier hated most—an obsequious priest—with what Collier’s opponents accused him of being himself—a vain and pompous priest—into a single character. In “Sir Charles Grandison,” we see the last of Jane Austen as a playwright. For Mr. Collins, like Richardson’s original “sycophant,” can be allowed to exist only within the pages of a novel.

NOTES

1The Juvenilia Press edition of Jane Austen’s play Sir Charles Grandison contains both a “Readers’ Edition” (1–24) and a “Diplomatic Edition” (25–53). All quotations are, for ease of reading, taken from the “Readers’ Edition,” except where indicated. For the dating of the manuscript, see Peterson, Introduction xii–xiii, xxviii–xxxviii.

2To the best of my knowledge, the abduction and attempted forced marriage are included in every abridged version, however short, of Richardson’s seven-volume novel. See Hunt.

3Brenda S. Cox enumerates some of them: “Jane’s letters refer to at least ninety clergymen she knew, and she and Cassandra also knew others. Cassandra was engaged to a clergyman. . . . Jane’s brother James followed his father as rector of Steventon. Her brother Henry became an Evangelical minister. . . . Edward . . . married a sister of clergymen and one of their sons became rector of Chawton” (11). Jane Austen also read books of the sermons of “her pompous Evangelical cousin, Edward Cooper” (13).

4The subtitle of the fifth edition of Collier’s Short View (1738) reflects the history of this pamphlet war: With the several Defences of the same. In answer to Mr. Congreve, Dr. Drake, &c.

5I assume here that the Austens performed Tom Thumb: A Tragedy (1st ed. 1730), a short farce with eleven speaking roles. (James Austen’s prologue is titled “Prologue to the Tragedy of Tom Thumb” [23]). It is not impossible that the Austens performed Fielding’s later, much-expanded version, with sixteen speaking roles, titled The Tragedy of Tragedies: The Life and Death of Tom Thumb the Great (1st ed. 1731). This version features a Parson who appears in one scene only to marry Tom Thumb and Huncamunca (2.9, pp. 34–36).

Priests are generally scarce in plays of the eighteenth century, but they do exist. The prolific and popular John O’Keefe’s musical farce Patrick in Prussia; or, Love in a Camp (1786) features a Roman Catholic priest, Father Luke, who likes his liquor a bit too much (the scapegrace Darby views him as one of his “singing-pot companions” [1.1, p. 6). But Father Luke does good to others and “is almost a man of virtue” (Halton 96). The Austens may well have known Patrick in Prussia, as they appear to have been fans of O’Keefe’s lyrics at least: Austen owned a print copy of the music for “The Plough Boy,” a song in O’Keefe’s comic opera The Farmer (1788), and her “First Act of a Comedy” (1793?) features a “Chorus of ploughboys” (J 218). For other sources and influences on the “First Act of a Comedy,” see McMaster, Peterson, and others 35 n59. I thank Gillian Dooley for her assistance with O’Keefe.

6Collier also wrote a full chapter on his objections to “Stage-poets [who] make their Principal Persons Vicious, and reward them at the End of the Play” (140). In The Chances, the protagonist Don John—the role Garrick himself played—is a libertine who partakes in the general happy ending. First Constantia is engaged but unmarried and at the play’s opening has just given birth. In Garrick’s version, Second Constantia runs away rather than sleep with the man her mother sold her to (and then robbed); in Villiers’s version, Second Constantia is unquestionably “Antonio’s whore” (“Dramatis Personae”). I assume here that the Austens chose Garrick’s edition, because it was very popular, copies would have been readily and cheaply available, and the Austens performed no other play written earlier than 1714. But Villiers’s unedited version was still in print and still being performed at the time.

7The pimp is Dominick in John Dryden’s The Spanish Friar (1681). Collier says that Dominick “is made a Pimp for Lorenzo; He is call’d a parcel of Holy Guts and Garbage, and said to have room in his Belly for his Church-steeple” (98). Mr. Horner in William Wycherley’s The Country Wife (1675) calls the churchman an atheist.

8An Ordinary in this context is someone, such as a bishop, who has jurisdiction over the priest.

9See, for instance, Sutherland’s introduction to J. E. Austen-Leigh’s Memoir. She argues that “Beyond a certain point the familial perspective is irrelevant, even dishonest” (xx).

10“Prologue to a Private Theatrical Exhibition at Steventon 1788” was most likely written for the performance of High Life Below Stairs, even though it does not name Townley’s play (Byrne 13–14). The prologue’s content is not closely linked to the play’s content, but the same may be said of James’s prologue to The Chances. The “Prologue to a Private Theatrical Exhibition” invites the audience to “view the Farce of private life” (James Austen 27, l. 38), which applies equally well to High Life and “The Visit.”

11Most clergymen only had a bachelor’s degree from either Oxford or Cambridge. “Those working for a doctor of divinity degree studied theology, but most students could not afford an advanced degree” (Cox 57). The fact that Richardson’s Sir Hargrave addresses the priest as “Doctor” suggests either that Sir Hargrave is mocking his poverty with an appellation the man could never hope to gain or that the man has fallen from some height to his present sorry state.

12The texts in the three manuscript volumes that she explicitly identifies as novels are “Frederic and Elfrida,” “Jack and Alice,” “The Beautifull Cassandra,” “The Three Sisters,” “Amelia Webster,” “Love and Freindship,” “Lesley Castle,” and “Catherine, or the Bower.” Most of the rest she terms “tales.”

13This dramatic text is included among Volume the Second’s “Scraps,” which are collectively dedicated to the infant Fanny Austen (later Knight).

14See Peterson, Hunt, and others (56–57 n21).

15There is some disagreement as to when Austen carried out most of her significant revisions to “First Impressions.” It may have undergone “revision for a number of years, perhaps up to 1803–04 or thereabouts” (Rogers xxx), in which case Austen was working on Mr. Collins’s character and the character of Sir Hargrave Pollexfen’s hired Clergyman at much the same time.