Why does Mr. Darcy stalk around the ballroom at the Meryton Assembly, refusing to dance or speak? Why, because he is a vampire aroused by the scent of all that human blood, of course. What if Mr. Bennet is so determined to foil the entail on Longbourn that he travels to London to meet a Dark Lord, who turns him into a vampire, and, to keep him company for eternity, he then transforms or “turns” his favorite daughter, Elizabeth? What if Jane is a weredog, and the were-hunting militia are in town? What if Elizabeth possesses extraordinary magical powers but is denied entrance to the men-only magical academy? What if Darcy and Elizabeth are forced to work together to extract magic from poetry to fill wands to send to the English mages fighting Napoleon’s mages at the front? What if Darcy was murdered by Wickham fifty years before the Bennets inherit Pemberley—will death hamper his remarkable sex life? (Answer: No.)

The world of fan fiction—fanfic of movies, TV shows, books, animé, comics, and even of real celebrities or sports teams—is a wild and vast one, and the smaller category of Pride and Prejudice fantasy-oriented fanfic (P&PFFF) is no different. There are fantastical creatures: dragons, witches/mages, zombies, were-creatures (bears, wolves, dragons, skunks, orangutans, platypuses), vampires, fairies and the Fae, ghosts, and aliens—but not unicorns, perhaps because in the popular imagination unicorns are solitary, unique creatures that do not live in social hierarchies. There are fantasy settings such as a steampunk future with airships, Oz, the planet AiJuran, and an alternative England with wyverns and wyrms. Some readers may find all this weird and possibly disturbing—disturbing not just for its fantasy content but for the idea that perhaps Austen fan fiction has just gone too far.

Maria Clara Pivato Biajoli notes the paradox that “while Austen’s popularity promotes her long-term life it leads, at the same time, to her death, so to speak, as other themes in her work are silenced.” Elise Barker concurs, observing that popularity causes a narrowing of reading and a simplification of characters as readers latch on to certain aspects of the novel—specifically the romance—at the expense of Austen’s “biting social commentary and sophisticated irony.” These concerns are completely valid, as exemplified in my recent encounter with an Uber driver who was convinced that Austen had created both the “tall, dark, and handsome” and the “enemies-to-lovers” tropes and also had written that best-seller Jane Eyre. It is easy to laugh at or even disdain a representation of Darcy as the Wizard of Oz, a vampire, or the Frog Prince.

Devoney Looser observes, however, that there have been many interpretations and presentations of Austen’s works and of Austen herself in the nearly two hundred years since her death. She asks us to challenge our assumption that we have the authority to say that this Darcy is correctly presented and that one is not (12). Fantasy versions of Pride and Prejudice can certainly test our boundaries, especially if we don’t care for the fantasy genre itself, but they do exhibit an amazing engagement with a well-loved novel and author, and, in the best examples, an amazing degree of creativity, wit, and, yes, on occasion, some social commentary. In a previous article I explored the range of physical artifacts (mugs, tees, wallpaper, etc.) on the market at the time of writing, dividing them into categories that fans could use to represent themselves: Romantic, Interactive, and Ironic. With fantasy versions of Pride and Prejudice, we already know that we are in the land of Interactive Irony—the question is how far will we go? What does fantasy offer the creative author that real-world-based fanfic does not?

It offers amusement and shock value for one thing—it’s just innately funny to some of us to think of Darcy as a vampire or a were-platypus. There are some additional reasons. For example, in some legendaria, dragons have a hierarchical system of dominance that equates well with Regency society. In other worlds, having one’s partner be a vampire or a werewolf whose bite could literally be life-changing inhibits achieving the state of HEA (Happy Ever After). Fantasy also offers a different way of exploring issues of colonialism, race, or gender-role privileges and expectations. I explored this world, examining a study group of eighty-one fantasy versions of Pride and Prejudice available on Amazon between October 2022 and April 2023: a total of 18,759 pages—that’s more than eighteen times through War and Peace or forty-five times through the real novel. This essay will detail that adventure and will also give the reader tools to help her select fan fiction that she will like in any fandom.

Study parameters

I found the eighty-one titles in this study by searching under the term “Pride and Prejudice and ____,” where the additional noun included the words fantasy, vampires, fairies, werewolves, etc. These titles represented almost all the writers publishing during that time (a dystopian/post apocalyptic Kindle title was corrupted, so I could not finish it and dropped it from the group; I may have missed a handful of late posters), but they did not cover the entire universe of P&PFFF. Since I counted only the first book in multivolume series, the total universe of P&PFFF during the period of study was significantly larger. For example, Maria Grace’s excellent Jane Austen’s Dragons series (R3) currently has twelve volumes, but I counted only the first one. The reason for this rule was that if I didn’t like a series (and there are many series), I wasn’t going to force myself to read all titles in it; to be fair, then, I only counted the first volume of a series. Some titles are novellas, and several are just chapters—this was true of some of the sensual titles (e.g., Camilla Barlowe’s The Darkest Kiss: A P&P Sensual Paranormal Intimate [R78; seventeen pages] and S. and J. Barton’s Fitzwilliam Darcy, Werewolf Hunter: A Paranormal P&P Sensual Intimate [R78; fifty-five pages]). These titles are also the ones that had to be purchased (usually for $2.99 or $3.99) rather than downloaded for free. This pricing could reflect the author’s desire to monetize her work; it also could be a mechanism to discourage the under-age reader who would have to use her parents’ credit card to purchase it. (See the warning below.)

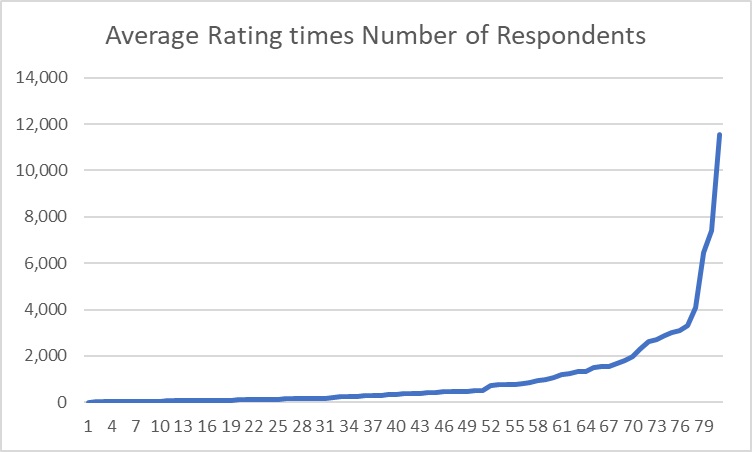

To obtain a scoring mechanism that did not include my personal biases (I like dragons, fairy tales, and magic, and dislike vampires and weres), I took the title’s average Amazon reader rating and multiplied it by the number of ratings given to get a composite score that represented popularity and reach. These scores ranged from the high of 11,533 for Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (Rank 1; average score of 4.2 times 2,746 raters) to a low of five for Lizzy’s PemBEARly Mate (Rank 81; average score of 2.3 and two raters). Note that to leave a review and a rating, the commenter must have purchased at least $50 of goods from Amazon within the year. Amazon also has an unexplained mechanism to weigh recent reviews more heavily than older ones. Flawed or not, one assumes that the algorithm is consistently applied to all the titles in the study.

This is a huge range! Clearly, some of Pride and Prejudice and Zombie’s popularity is connected to the movie of the same name—the next highest score was 7,403. The most interesting observation about the data, however, is its median (the composite score that has an equal number of entries above and below the mark): an extraordinarily low 346 including Pride and Prejudice and Zombies; 336 dropping that title. The results are captured in the chart below where the X-axis represents the number of entries, and the Y-axis is the composite score. The raw data are given in the table at the end of this paper.

The low median depicted in this asymmetrical (long-tailed) distribution of the titles’ popularity is the graphical representation not only of this study but also of the old joke about the birthday child who enters a room filled with manure and starts digging through it with her bare hands, happily shrieking: “With all this shit there has to be a pony here somewhere!”

Reader, there was a lot of shit.

But there were also some wonderful ponies.

So, Adventurer, grab your walking stick and your pocket-handkerchiefs, and let’s go find them!

Here be dragons: What is fanfic and what genres of fantasy are represented in the study group?

Fan fiction is defined as unauthorized creative work written by non-professional writers, usually within a community of fans who comment upon the work as it is in progress. It uses canon characters, settings, and plot points but can expand beyond them to AUs (Alternative Universes) or can add characters or plots from other books such as, in this study, Oz, Frankenstein, or Cinderella. While I only read titles published on Amazon because I wanted to use its consistent evaluation system, it is evident from the back matter of many, where authors thank readers for their comments and contributions, that they were initially published in a serial fashion on a platform such as https://www.fanfiction.net/, a popular posting site.

The fantasy genre now has many sub-categories, identified by vlogger Jay Kennedy. Categories (below) that I saw in the study group are in bold; note that a work can fall into multiple categories. Kennedy’s categories, in no particular order, are: High, Epic, Low, Urban, Paranormal, Historical, Comedic, Portal, Dark, Grimdark, Military/Flintlock, Steampunk, Heroic Fantasy, Quest, Sword & Sorcery, Alternative History, Arthurian, Assassin, Christian, Magic Realism, Fairytale/Fable, Romance, Erotica, Mythopoeia, Gaslight/Gaslamp, Fantasy of Manners, Court Intrigue, Swashbuckling, Superhero, Science Fantasy, Dystopian/Post-Apocalyptic, and Coming-of-age. To outsiders these distinctions may seem peculiar, but fantasy readers enjoy their niches just as mystery readers do.

While fantasy tales should follow the normal rules of good plot and character development, there are some additional questions that the author exploring fantasy can consider:

1. What kind of creature is the hero or what does he or she transform into? A Darcy who transforms into a dragon, a bear, or a wolf is very different from one who transforms into a platypus. In Nazarian’s mash-upPride and Platypus: Mr. Darcy’s Dreadful Secret(R48), all the gentlemen of England transform into a beast at the full moon, and there is competition over the size and elegance of their cages that they keep handy to be incarcerated in. For example, Mr. Bennet transforms into a jowly, elderly lion who keeps forgetting to take off his spectacles during the transformation. The self-important Mr. Collins—with the biggest cage the girls have seen (is this a euphemism for something?)—is unaware that he transforms into a skunk.

2. Does the creature have control over the transformation? A Darcy who helplessly transforms into a were-creature at the full of the moon is quite different from one who transforms at will, or when aroused by anger or desire. In the latter cases he must exert more control over himself—hence his dislike of society.

3. Does the creature need to be nude to transform? Does the creature require special food for recovery? How will the transformation fit the rules of Regency society?

4. Does anything impede the creature? In some legendaria running water or iron impedes witches; silver impedes the Fae; and crucifixes, garlic, and sunlight impede the vampire. Does vampire Darcy have to sleep during the day? Does Elizabeth’s cross—seen only in movies—protect her? Answers to these questions can become interesting plot points.

5. Does a casual bite/scratch transform the beloved, or does it take intent? In some legendaria a vampire can take blood from a person without turning her into a vampire; in others, a careless bite or scratch will turn the beloved into a vamp or a were. How will this possibility affect the Darcys’ married life?

6. To what extent are Mundanes (a term used in the fantasy world for non-magical people; extrapolatable to anyone who does not participate in the preferred fandom) aware of magic? Is magic permitted, or is it a cause for persecution? An England in which the dragons or weres must hide is different from one in which magical powers are revered or at least tolerated.

7. Is Elizabeth permitted access to magic, or not? In many legendaria, her inability to be trained as a mage or witch at a formal academy serves as a stand-in for women’s historical lack of access to education and power. In such stories Elizabeth is not permitted to openly study magic. Often her magical powers are therefore different from and frequently stronger than those of the academically trained Mr. Darcy, or she may have access to “wild” magic, which may enable her to think outside the box when at war with Napoleon’s academic mages. Maria Grace explores this concept extensively in her twelve-volume series, as do Monica Fairview inDangerous Magic(R8) and Victoria Kincaid in Mages and Mysteries (R11).

8. Is being magical something that the character embraces or struggles with? This issue is particularly important to vampires since, although they can be killed, they are otherwise immortal. If Elizabeth, Georgiana, and Colonel Fitzwilliam are all immortal vampires, will Darcy choose to join the people he loves the most? Who will turn him?

Despite the title of this paper, dragons are the focus of only three titles in the study, while vampires dominate with seventeen titles, general magic with fourteen, and fairies/fairytales with thirteen. As I read the offerings, I concluded that the type of magical creature was almost less important than the type of storytelling. The titles fall into the following categories:

Mashups: Four titles fall into this category, in which about 85% of the text is Austen’s (she is always listed as first author), with the rest being invented. The idea of a mashup comes from the world of electronic music, where the DJ takes the drum and instrumental tracks of one song and layers the vocal tracks of another on top, altering key and rhythm, if necessary, to create a new work. The word was first applied to a book by Carolyn Kellog in her review of Seth Grahame-Smith’s 2009 novel Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. While mashups can have a clever concept, they don’t always satisfy the audience—as in the example of a reader of Elizabeth Bennet, Shapechanger (R50), by Austen and Laer Carroll, who writes a popular shapechanger-science fiction series. On March 15, 2021, a reader, Bicar, wrote: “I had to quit up half way through the book. I kept waiting for the shapechanger part of the story and there was only a mention of an instance or three in the first half of the book. My thought was that someone else wrote the book as it didn’t read anything like the other Laer Carroll books.” Bicar was confused and bored by the bulk of the text that was Austen’s.

Retellings: Retellings retain most of the canon plot elements and characters but tell the story from a new point of view or in a different setting/world or genre. For example, the wonderfully-pen-named Cassandra B. Leigh’s Darcy the Terrible (R58), is a retelling set in Oz (the book version, not the movie version, we are told). Louisa Hurst is the witch who is squashed by the house. You can guess who Caroline is.

A darker and more intense retelling is M. Verant’s Miss Bennet’s Dragon (R6), which brings in themes of female power in a patriarchal society, evangelism, free choice, and slavery. Influenced by Leigh Hunt, Mary has become a vegetarian. Elizabeth, who is experiencing strange and intense interactions with the draca bound to every estate, notices that Darcy refuses to eat Lady Catherine’s overly sweet desserts and declines to take sugar in his tea; he is participating in the sugar boycott of the abolitionists and deplores Lady Catherine’s boast that Rosings is supported by the sugar plantations and the slave trade. He later tells Lizzy that he is working to move his money and Georgiana’s out of slave-trade-based sources. In addition to this nod to the abolition movement, Verant’s work is also unusual in that it is one of the few to be told from Elizabeth’s first-person point of view. More typically these tales are in the third person, to allow the reader to put herself more easily in the shoes of the character that Darcy falls in love with.

Variations and Continuations: The most popular category, Variations includes prequels, sequels, and alternative endings or scenes, or continuations of characters’ stories. Variations include some but not all key canon characters and can include some but not all canon plot elements. An example is A Disguise of the Worst Sort (R17), in which Elizabeth has been forced into accepting Darcy’s proposal and his subsequent invitation to visit Pemberley to get to know him better. In the carriage, Caroline, who has purchased a spell from a witch, switches bodies with Elizabeth. Will Darcy be able to choose correctly between faux-Elizabeth, who wears Caroline’s preferred color, orange, and faux-Caroline, who wears Lizzy’s “favorite” green (although Austen actually tells us that Elizabeth’s favorite color is yellow [24 May 1813]) and exhibits her enchanting personality? Can Elizabeth return to her body before the spell becomes permanent?

Variations can rocket so wildly out of canon (OOC) that I was tempted to create an additional category for them. An example of this is A Vampire in Rosings Park (R72), in which Darcy hosts a house party with various canonical and non-canonical characters, tells them that they cannot leave, and recommends that they all stay together, a suggestion that they ignore. A terrible creature (a character from the canon) kills the guests off, one by one, until Darcy and Elizabeth can slay it.

|

|

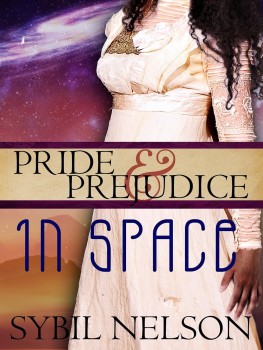

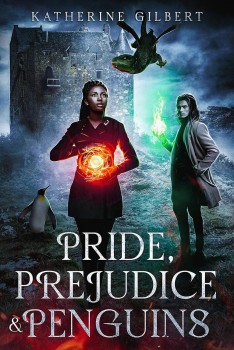

A comparison of a Retelling versus a Variation shows us some of the richness and creativity of the genre. Let’s examine Pride and Prejudice in Space (R59) and Pride, Prejudice & Penguins: A More in Heaven and Earth Magical Academy P&P Variation (R71). As you see from the covers, the heroines of both works are Black—the only two in the study, although in a third title Darcy, and therefore Anne de Bourgh, are one-quarter African. (Their grandfather was a counselor to the king in the African land of Oyo.)

Pride and Prejudice in Space is a Retelling set on the plant AiJalon in the future in which the dark-skinned AiJalonians are the dominant race—Mr. Darkeny is tall, handsome, and very dark indeed, with royal tribal markings on his neck near his gills—and the white-skinned humans are looked down upon, although the Bonnezon girls are mixed race, and Elloree speaks old Ai with great fluency. It is a rollicking space opera that concludes with Darkeny and Elloree on the back of a future-motorcycle blazing into a human slum to rescue Ly’dina, who is about to be sold into intergalactic white slavery. It also includes one of the most intriguing and surprising openings and endings of any P&PFFF. However wild, this story has all the canon plot points and characters.

Pride, Prejudice & Penguins is a Young Adult Variation. Jane and Elizabeth, after some family tribulations (their father is a Nigerian sorcerer at odds with magical authorities), are newly enrolled at a school for magical teens in the north of England with a more diverse student base than Hogwarts, including a human raised by werewolves, a transgender witch, a dryad, and an ogre. Lizzy not only has difficulty with magic, but she suffers from the rare spell “Narrative Syndrome,” in which she must fight being sucked into Austen’s story.

Spin-Offs: Spin-offs feature some canon characters and plot elements, but they are fundamentally entirely new stories. Examples include an excellent series by Joyce Harmon, starting with Mary Bennet and the Bingley Codex (R2), in which Mary solves various magical mysteries. The first in another series is Maria Grace’s Pemberley: Mr. Darcy’s Dragon (R3), in which the estates are named after the dragon that lives there (Longbourn is a crochety old dragon who hoards salt), and Elizabeth can speak to any dragon. Unlike Variations and Retellings, Spin-offs tend to have the greatest amount of “world-building”—that is, created worlds that have their own rules, creatures, and internal logic. Grace’s world, for example, is inhabited by “major” and “minor” dragons, tiny fairy dragons, and sea dragons like Captain Wentworth’s faithful Kellynch. Each type of dragon has its place in the hierarchy and specific powers and capabilities.

Fairies and Fairytales: A fairytale that links a canon character to a traditional story like Beauty and the Beast is a category that can appear in both Variations and Retellings. One charming example is Courtney’s Beauty and Mr. Darcy (R12), in which all six girls appear as heroines of various classic fairytales. In many fantasy legendaria, however, “fairies” are quite different from the “Fae.” While the former are cute, the latter are usually dangerous, sexy, and morally shifty—the kind of creature that lures humans to their kingdoms where one hundred years pass as a day. See the warning below from Reverend Fordyce.

Outliers: This category contains titles written by established authors; two of them feature Jane herself as a vampire: Michael Thomas Ford’s Jane Bites Back (R37) and Janet Mullaney’s Jane and the Damned (R52). While titles like these are included in the study, in part because several of them were influential in affecting the genre, they do not meet the criteria of “real” fanfic. Jonathan Pinnock’s raunchy Mrs. Darcy Versus the Aliens (R75) also has a tone that is different from the typical fanfic: it is absurdist in a Monty Python/Terry Pratchett way.

The Reverend James Fordyce advises the Adventurer

As to works of imagination,” Reverend Fordyce observes in one sermon, “it is allowed on all hands that the female mind is disposed to be peculiarly fond of them.” He recommends reading “Fables, Visions, Allegories, and such like compositions” (1: 215), although he was certainly not thinking of fables and visions about dragons and fairies. In a later sermon he adds the warning that “[y]oung people, we know, are often corrupted by bad books” (2: 10), and here we can be perfectly sure that he would be horrified by some of the entries in the study and would advise parents to monitor their daughters’ reading carefully.

Bluntly speaking, much fanfic, including P&PFFF, centers on sex and is often extremely explicit: at least twelve of the titles in the study were X-rated. This warning is important for fantasy Pride and Prejudice readers because the fairy tale versions could attract the young Austen fan who then might assume that all the stories in the fantasy genre are sweet and cute. This is not the case! While FanFiction.Net uses an age-based content rating system that runs from K to NC17 and does not permit posting of any “mature” work, fanfic on Amazon is an unregulated market, and the reader ratings do not convey any trigger content. Covers featuring a man’s chiseled torso (with or without a white shirt) are one clue that the contents are for the mature reader. Some authors will provide code words in the blurb such as “sweet,” “clean,” “chaste,” or “suitable for the young teen”; on the other end of the spectrum, you will see words like “sensual,” “sexy,” or “hot.” Many times, however, there were no code words, and I was startled by the content.

|

|

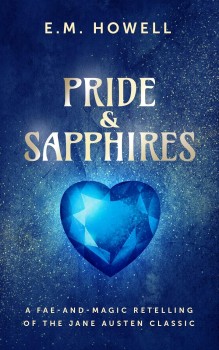

The Reader infers correctly that Lizzy’s PemBEARly Mate contains sex scenes—but Pride & Sapphire is even more explicit, and there are no clues in the authors’ blurbs that either is X-rated. The cover on the left (R81) accurately signals the content: in a small town in Vermont most of the men are were-bears. When each finds his Happily Ever After mate, he bites her at the climax of their human lovemaking. She can then transform into a bear, and they have fantastic bear sex in the woods. Darcy’s bear is bigger than Wickham’s bear. The cover on the right (R79), however, gives no such signal. The story is about two warring Fae kingdoms, and the protagonists (who do not have canon names; this work is so OOC that had the author not claimed it as Pride and Prejudice fanfic I wouldn’t have recognized it as such) engage in extremely explicit sex within moments of meeting each other, even though she dislikes him in the tired, old, and inaccurate enemies-to-lovers trope.

Pride & Prejudice Fantasy Fanfic—good or bad?

Borrowing from Tolstoy, we might say that all good books are alike; all bad books are bad in their own way. What makes good P&PFFF? The answer is simple: accuracy to the internal rules of the fantasy world and an interesting plot that supports that world and sets up interesting problems for interesting characters. Extra credit goes to authors—and there are many!—who weave in quotations from other Austen works, including the letters and the juvenilia, or who reference The Mysteries of Udolpho, Fordyce, or other contemporary authors or real people such as Arthur, Earl (not yet Duke!) of Wellington. A final critical attribute for me is that the P&PFFF must be funny. What constitutes bad fantasy fanfic? Worlds whose magic or fantasy rules are unclear, illogical, or inconsistently applied, plot holes you could fly a dragon through, and stories that are just plain dull or, to me, distasteful. Finally, many are badly written.

Fan fiction rarely has an editor or even a “beta reader,” and many works are riddled with misspellings, typos, sentence fragments, run-on sentences, and awkward modifiers, such as she “folded her arms under her spare bosom” (A Witch for Mr. Darcy [R22] 76). They exhibit a lack of understanding of the meaning of historical words: a “megrim” is not a “migraine,” a “groomsman” is not the guy who takes care of your horse, and a “smithy” is not the guy with the hammer and anvil. Incorrect homonyms abound: examples include “free reign” rather than “free rein,” “baited breath,” or the following from Pemberley Haunted (R38):

A bell sounded, causing Kitty to pause on the stairs. “Is that not the chapel bell? I thought it was only wrung to announce births, deaths, fires, and imminent attack. Why is it wringing now?” (253)

Curfew shall not wring tonight, and spellcheck doesn’t catch everything!

Sometimes one simply does not know what the author was thinking. There are weird characterizations, such as this one in Power and Prestige (R39), when Darcy invites Mr. Gardiner to fish in the stream at Pemberley: “Mr [Gardiner] tried for a calm ‘thank you’ as he pulled on his coat tails in utter glee” (133). A grown man tugging on his coat tails? There are peculiar word choices: for example, when Bingley teases Darcy about how awful he is on a Sunday evening, the narrator of Pulse and Prejudice: The Confession of Mr. Darcy, Vampire (R31) comments that Darcy “did not know what had provoked Bingley’s quinine” (50). Quinine? Perhaps quip or choler? Querulousness? In Darcy Bites (R45), Elizabeth must listen to the “laminations” (178) of her sisters. And in Steampunk Darcy (R42), teenage Georgiana rebels against her half-brother Fitzwilliam’s “impossible expectations,” feeling that she is falling short. She’s tired of being good and longs instead “to be viled, just once, to stop pretending to be a young lady who followed all the rules.” She looks to their other, wicked half-brother, Rich, who breaks all the rules and is indeed vile: “She’d heard the rumors. She’d read the society columns. She knew about all the scandals that he left in his wash” (56). Dear Georgiana! Despite Bertie Wooster’s success in describing Jeeves as being, if not precisely disgruntled, not perfectly gruntled, you just can’t do that there here to the word “revile.” And “wake” and “wash” are not synonyms, even if they share two letters. As a final example, in Vampire Darcy’s Desire (R24) we have the following inexplicable passage:

A dreadful, guilt-ridden remorse filled [Darcy’s] tone. “I apologize if my proposal brought you from form with your family.”

Elizabeth giggled. “Believe me, Mr. Darcy, I am often from form with my family.” (Italics original; n.p.)

I am feeling a little from form myself.

Some titles have slow pacing or plot holes revealing the inexperienced author, although I don’t necessarily think that these flaws make them bad—just not memorable. One, Voices in the Dark, (R27), is indeed extraordinarily dark. After Mr. Bennet dies, Elizabeth is abandoned by the rest of the family (Jane reveals that she has never cared for Lizzy) and must go as a companion to the (literally) demonic Lady Catherine, who is systematically poisoning Anne and has imprisoned Darcy in the dungeon at Rosings. Some are just not to my taste. And with demons and vampires, as well as with the sensual titles, many authors lose sight of Austen’s comic side. Sex might sell, but it isn’t funny, and I dearly love a laugh. The good news is that many of the titles are competently crafted; many are charming, sweet, and funny; some are brilliant; and several of the authors are so good that I read all the titles in their P&PFFF series and, in some cases, even have gone to their backlist.

An aspect of Jane Austen fanfic that is not true of other fandoms is that, while Darcy and/or Elizabeth might start out a story involved with someone else in a HFN (Happy For Now) relationship, by definition they must end up together, HEA. This outcome is so beloved and inevitable that there is a special acronym for it (the fanfic world is rife with acronyms, many used to indicate the level or nature of the sex involved, or how far in- or out-of-canon it is): ODC. I puzzled over this acronym that does not appear in fan fiction dictionaries until it was revealed in a reader review: Our Dear Couple.

Readers new to Pride and Prejudice fanfic may be accustomed to authors who have written many works in a single genre (e.g., Agatha Christie for mysteries), those who have written books around a single character like Harry Potter, those who have written about a single place like Narnia, but they may be dumbfounded by the fanfic writers who write the same story over and over. ODC always end up HEA. Even if one of them is dead (The Haunting of Miss Bennet: A Paranormal Sensual Intimate [R62]). Or in a coma (Haunting Mr Darcy; A Spirited Courtship [R9]).

The Darcy fixation means that many writers have written multiple works about him, often under many pen names. A by no means isolated example of this obsession with ODC and Darcy is Valerie Lennox, whose real name appears to be V. J. Chambers and who also writes under the name Jove Chambers. Her backlist includes this exhausting group of Darcy-oriented tales:

| Mr. Darcy and the Island | Mr. Darcy and the Governess | |

| Mr. Darcy and Mrs. Fitzwilliam | Mr. Darcy the Rake | |

| Entrancing Mr. Darcy | Finding Mr. Darcy | |

| Beyond Mr. Darcy’ Reach | Barely Betrothed to Mr. Darcy | |

| Compromised by Mr. Darcy | Mr. Darcy, the Beast | |

| Mr. Darcy and the Lost Slipper | In the Tower with Mr. Darcy | |

| Mr. Darcy’s Downfall | Mr. Darcy, the Dance, & Desire | |

| Pledged to Mr. Darcy | Mr. Darcy’s Courtesan | |

| The Dread Mr. Darcy | Escape with Mr. Darcy | |

| The Scandalous Mr. Darcy |

Let’s have a little ChatGPT

Could any of the titles have been created by Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer? ChatGPT is not a search engine but a form of language parrot, able to write based on the works it has been “fed.” I believe not, for two reasons. First, most of the entries appeared before ChatGPT appeared circa November 2022. Second, a ChatGPT result—at least at present—is simultaneously better and worse than even the worst of the fanfic.

ChatGPT Gis easy to use. I asked it to write a proposal between Darcy and Elizabeth, and it promptly gave me them wandering the grounds of Pemberley by moonlight. I suggested that Darcy was a werewolf and Lizzy a vampire, and it obligingly gave me a ruined castle, his powerful frame and rugged charm, and her scarlet lips. I then told it that Darcy was an alien and Elizabeth a mermaid. It provided something in which “her luminous tail creat[ed] a kaleidoscope of colors in the cosmic abyss,” and when he touched her hand cosmic rays flooded her aquatic chest—grammatically correct in a way that the worst-written fanfic is not, but also flat in affect and by no means as creative!

There and back again: What happens to the characters?

The fantasy world allows the writer great latitude in changing canon characters or plot elements, and a brief review of these choices shows the range of creativity in the genre. Some characters remain as they are in canon; others are experimented with and become more complex; two non-canonical characters have taken on a permanent life of their own in the fanfic world.

Mrs. Bennet, Jane, Mr. Bingley, and Anne de Bourgh, for example, generally retain their canon characteristics, and writers do not often explore alternative destinies for them. Kitty gets one or two titles oriented to her, such as in Jackie Wellman’s Mr. Darcy and the Haunted Manor (R63)—book nine of what is currently an eighteen-book series of “Mr. Darcy’s Chronicles”; in it she plays a Catherine Morland-like role, solving a ghostly mystery. Her character is not deeply explored. Lady Catherine, predictably, often appears as a demon or dragon who must be slain. Mr. Bennet is not regarded with much sympathy; he is often shown as an even worse father than he appears in canon—or perhaps a better one, depending on whether you regard his turning himself and Elizabeth into undying vampires in order to thwart the entail and provide for his wife and the rest of the girls as a good or a bad action (Darkness Falls Upon Pemberley [R35]).

Mr. Collins usually remains the buffoon that he is in canon (in one title he is represented by a were-orangutan; in another by a were-skunk), but in a couple of titles he grows to become a more likeable character. In Beauty and Mr. Darcy (R12), he is the Frog Prince (Charlotte drops her gold locket in the water; he jumps in to save it, and then proposes) who learns to laugh at and defy Lady Catherine and who matures into a good father and a loving husband.

Mr. Wickham dies at the hands of many characters in many gruesome ways—gangrene of the gentleman parts being the worst one.

Caroline Bingley generally remains a dislikeable character, bent on foiling Elizabeth’s romance. In Courtney’s A Disguise of the Worst Sort (R17) she buys a spell to change bodies with Elizabeth: will Darcy be able to see below the lovely appearance of Elizabeth to the shallow Caroline underneath? In other titles, while she dies heroically—in one book she gallops bravely down the maw of a fearsome wyrm to stab it through the roof of its mouth; in another she is gut-shot by a plasma blaster as she throws herself in front of Darcy to save him from his evil half-brother—she remains an unpleasant character.

Lydia is explored more deeply. In one title she appears as a truly frightening demon, but in several others, she is redeemed or at least is on the road to self-improvement. For example, in Sarah Courtney’s Beauty and Mr. Darcy (R12), in which all six girls, including Charlotte, are represented by fairy tales, she is Snow White yearning for male attention as she gets none from Mr. Bennet. Under the wise guidance of Colonel Forster and six kindly and well-educated gentlemen officers, she gradually becomes more mature, reading Edmund Burke and taking an interest in politics.

Mary is the character with the widest range of possibilities; clearly, authors feel sympathy for her, stuck awkwardly between the two silly sisters and the two good ones. She frequently grows beautiful, losing her glasses and becoming hot in the famous movie trope. In other outcomes she is famed for her erudition, develops magical powers, becomes a magical sleuth, turns out to be a Fae changeling and marries a Fae warrior, enters into a Sapphic relationship with Georgiana, enters into a Sapphic relationship with Caroline Bingley, marries Mr. Collins, and throws a volume of Fordyce’s Sermons to Young Women at the evil sorcerer, causing him to trip and break his neck. (Not all at the same time.)

Elizabeth is only once represented as a vampire. More commonly, she has magic that is different from and superior to that of the academically trained Darcy. She is active and resourceful, communicating fearlessly with dragons or growing hoarse from reading Mysteries of Udolpho aloud to Titania, Queen of the Sidhe. She remains the reader’s avatar for being fallen in love with by Darcy.

Darcy is the focus of most of the tales. The writer wants Darcy to fall in love with Elizabeth/the reader over and over again. Darcy is varyingly represented as Sleeping Beauty, the Frog Prince, the Beast, the Wizard of Oz, a vampire (very frequently!), a were-wolf/bear/dragon/platypus, a werewolf hunter, a vampire hunter, and the half-Fae Crown Prince of the Summer Court of Faerie. He also appears as one-quarter African with dark hair and piercing green eyes and as a stone statue courtesy of his evil Matlock cousin. He is generally a cardboard hero—only in a handful of titles such as Verant’s Miss Bennet’s Dragon (R6) does he develop more complex characteristics.

One of the most interesting aspects of the fandom in both fantasy and mundane versions of Pride and Prejudice is the coming to life of Darcy’s noble uncle, “the Earl of ___.” In the gaming world this is the equivalent of a Non Player Character (NPCs are the characters that can only say what they are programmed to say) becoming sentient and self-aware. Austen does not name her character, but, in the 1995 BBC series written by Andrew Davies, Charlotte names him the Earl of Matlock. The identification has solidified in all categories of JAFF! In the fantasy world, Lord and Lady Matlock often play a key role, sometimes nurturing the protagonists, sometimes defending the old, male-dominated order that does not support Elizabeth and her magic, and sometimes actively fighting in the battle against evil. We know that Colonel Fitzwilliam, to whom Austen does not give a first name but who, in the fandom, usually goes by Richard, is the younger son. Even as a vampire, he continues in his genial and supportive role to his cousins. (It is his elder brother, the heir, who turns Darcy into stone in Pemberley by Moonlight [R18].)

Questing for fanfic? Examine the paratext

Even if the title is available for free on Kindle, how does the Adventurer find something that she will like to read that will not waste her time? The answer is to examine the paratext, defined as all the materials surrounding the text itself: the cover art, the blurb, any code words for sexual or trigger content, the number of pages (I found that shorter works tended to be the sensual chapters that I didn’t care for), the author’s bio, etc. For example, if the author has been published by a traditional publisher or has won or been nominated for major awards such as the Hugo or the Nebula, you can be sure that the work will at least be competently written, even if not to your taste.

Ratings are helpful but not infallible. In my personal adventure I found that a composite rating over 1,000 meant that I was more likely than not to enjoy the work, though there were still some high-ranking titles that I felt were dull, sophomoric, or distasteful. A low composite score, however, did not necessarily mean that I wouldn’t like the work. Because the scores are built over time, a newly published work that has not yet gained traction will have a low composite score. The most useful tip is to read the reviews. How many are there? Do they reach consensus? Reviewers leave honest, often very detailed comments, even explaining why they deducted points for the rating they gave. This interaction is part of the community aspect of fanfiction writing.

These tips apply to Amazon and its rating system and are applicable to all genres of fanfic. They are also generally translatable to FanFiction.Net or other such boards. A work with many likes or an author with many followers will give you a similar indication of popularity, which, in the fanfic world, is the closest proxy there is for quality.

Some conclusions

This essay represents the dip of a cup into the river of Pride and Prejudice fantasy creativity during a six-month period in 2022–2023. This river has rapids that are light, bright, and sparkling as well as eddies of murky and even distasteful water. But, Adventurer, by the time you read this, the P&PFFF river will have swept on and changed its banks: ratings and readership numbers will have changed, new titles will have appeared, and some that I refer to in the chart below may have vanished as, apparently when a fanfic writer goes mainstream, she often takes down her fanfic publications so as not to compete with herself.

The Internet has provided people with an historically unparalleled, low-cost way of expressing themselves and their passion (other than graffiti on bathroom walls). This creativity is intrinsically a good thing, even if the final product is rather bad and only read by a few readers. But would Jane have approved? Would she really have been a DragonRider as the title of this paper suggests?

I think that Jane would have been amused and rather flattered, and that she might want some of the money involved. For two reasons, however, I do not think she herself would have written a fantasy version of any of her stories. First, while we know that she and her family enjoyed reading “horrid” novels, Austen chose to write a parody, rather than a real gothic novel. Gothics are not comic, and she said that could not write anything serious, except to save her life (1 April 1816). Second, I think she would not write a fantasy because, unlike the gothic novels she enjoyed in which most supernatural events are revealed as being due to human agency, modern fantasy novels treat the creatures as real, and I doubt that her faith would permit her to populate a landscape with real vampires and dragons. These are creatures that do not have souls (or, in the case of vampires, beating hearts), and they cannot know God nor be saved by Him. I think she would be shocked at and perplexed by our obsession with fantastical creatures.

We have a different perspective that gives us a different view—a view formed by 200 additional years of fantasy explorations that make these creatures a little more commonplace, from Dracula to Twilight, from Lord of the Rings to Dragonriders of Pern, from Narnia to Hogwarts. While it can be a perilous adventure to explore Pride and Prejudice fantasy fan fiction, there are many treasures to be found.

APPENDIX

The chart below includes the titles in the study ranked from highest to lowest by their compound score. The chart identifies rank, type of fantasy character, storytelling category, number of pages, title, author, date of “publication,” the average rating and number of raters as of mid-April 2023, and the compound score. I indicated in bold some of the titles that I liked best, but there were other good reads as well.