The town of Southampton is somewhat overlooked in the biography of Jane Austen, so for the special 250th anniversary of her birth, a year of events was organized to raise the profile of Austen’s connections with the town. These events included two exhibitions: the first, an exhibition of Austen’s writing slope, was its only appearance in England before going off on a world tour; the second was an exhibition in Sea City Museum that focused on the town and people whom Jane Austen knew. Just as Austen herself recommended a focus on three or four families as the best number to work with for a novel, for the exhibition A Very Respectable Company: Jane Austen & Her Southampton Circle (27 March–31 October 2025), it was decided to feature three Southampton families with whom she was intimate.

The exhibition space at Sea City Museum for A Very Respectable Company.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

“My idea of good company, Mr. Elliot, is the company of clever, well-informed people, who have a great deal of conversation; that is what I call good company.”—Persuasion (162)

Jane Austen’s circle of friends and neighbors included Charlotte Fitzhugh, a very close friend of the actress Sarah Siddons, and Charlotte’s sister-in-law, Mary Lance, wealthy wife of the East India Company merchant David Lance; Anne Middleton, a mixed-race plantation heiress from Jamaica; and Jane’s cousins Elizabeth Austen, married to John Butler Harrison II, wine merchant and politician, and Harriet Austen, a close friend of the artist Tobias Young. Descendants of these families loaned items from private family collections to create the exhibition alongside loans from Southampton Archives, including items donated by Helena Austen Harrison, the last member of the Austen family to live in Southampton.

Jane Austen in Southampton

Jane Austen spent three periods of her life in Southampton. Her first stint was as a child in 1783 in the company of her sister, Cassandra; her cousin Jane Cooper; and the woman charged with educating the girls, Mrs. Cawley. The visit was brief as all the girls contracted endemic typhus (putrid fever), a disease spread by troops massing in Southampton during the American Revolutionary and Anglo-French War. Ten years later Jane and Cassandra returned for an extended visit with their second cousin Elizabeth Austen, who had left Tonbridge to marry John Butler Harrison II. Jane stood as godmother to the couple’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth Matilda, during this visit. In 1806 Jane Austen returned again, this time as a resident alongside her widowed mother; her sister, Cassandra; her brother Francis and his new wife, Mary; and family friend Martha Lloyd. This period was the focus of the exhibition.

High Street from Bargate (1812). Ackermann and Co.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Georgian Southampton: Its spa, Netley Abbey, and Castle Square

The exhibition opened with a display illustrating the Southampton of 1800, when 8,000 people were living largely within the town’s medieval walls. The town had reinvented itself as a watering-place around 1720, and by 1798 it was described as “elegant, well-built” with a “picturesque appearance” (Universal British Directory 461). Many of the medieval buildings had been given new frontages with sash windows; to others were added bow windows, pediments, and stuccoed exteriors. New facilities had developed to serve the growing number of visitors: a theatre, built in 1805, coffee houses, tea rooms, and circulating libraries such as those of the printers Thomas Baker and Thomas Skelton.

When the town discovered a mineral spa, it could promote itself as a spa resort as well as a watering place for bathing. Health is a theme that runs through Austen’s novels and is a topic of huge interest in the letters and journals of her friends and relations. A whole industry had grown up in the town around health tourism, and it was central to Southampton’s popularity. The cures associated with taking the flounce (i.e., being dipped in the sea) and imbibing the waters were parodied in Jane Austen’s unfinished novel Sanditon. The attributes Austen bestowed on the waters of her resort—“anti-spasmodic, anti-pulmonary, anti-sceptic, anti-bilious and anti-rheumatic” (LM 148)—could have been plucked from the promotional literature produced in Southampton: “Southampton’s chalybeate spring water was especially helpful in the treatment of jaundice, scurvy, paralytic disorders, barrenness in females, green and yellow fever, intestinal blockages, feebleness experienced by young females, fainting fits, lassitude and other female complaints” (Southampton Guide 47).

Southampton’s original spa fountain in the exhibition space.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

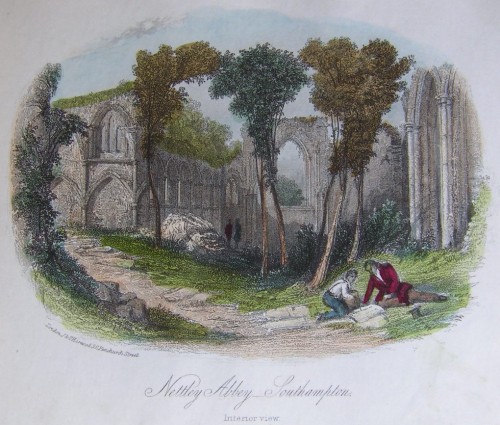

Baker and Skelton, printers and proprietors of circulating libraries, printed not only novels but also pamphlets and books promoting the town and local attractions, such as the ruins of Netley Abbey.

Netley Abbey, Southampton (c. 1840). J. & F. Harwood.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Netley Abbey was promoted as “the great Lion of the neighbourhood” and attracted many visitors, including the Austens (Freeling 59–71). People made water parties to the ruins for picnics, and there were often events involving music and dancing. Above all, Netley Abbey inspired artists, poets, novelists, and musicians. Images of the ruins appeared in paintings and engravings, and the ruins served as the setting for operas. Netley Abbey inspired leading promoters of the gothic, Horace Walpole and the poet Thomas Gray, who even spent the night there. It was not long after Austen’s visit to the town in 1793 that she began Susan, which later became Northanger Abbey. Perhaps visiting the ruins again when the family moved to Southampton, or the fact that they were living in a house built in the Middle Ages, with a garden bounded by the old town walls and overlooked by a mock-gothic castle, prompted Austen to write to the publisher who still held the unpublished Susan and demand its return.

Residents

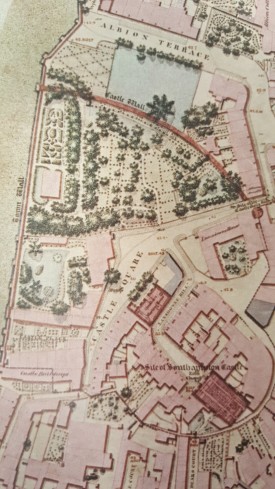

The Austen family had pooled their incomes to rent a suitable property in which the combined household could live. Francis Austen was on half pay after the victory of Trafalgar had neutralized the threat of the French navy, but he still needed to be close to Portsmouth, home of the Royal Navy. Southampton was an ideal location, providing all the polite amenities a gentry family required. As the residence of many influential naval admirals, such as Admiral Bertie, this proximity might help the naval careers of both Francis and Charles Austen. In addition, the town attracted several East India Company families. Francis Austen had done great service to the company, but it owed him money, so paying visits to families like the Lances and Fitzhughs could also prove beneficial. The family first stayed on the High Street, where lodgings were notoriously expensive and in short supply, but then they moved to a substantial property, 2 Castle Square.

Castle Square, detail from Ordnance Survey Map (1846). Courtesy of Southampton Archives. |

A View of the Marquis of Lansdowne’s Castle, Southampton, by S. J. Neele after Tobias Young. |

The leading aristocratic residents in the town were the Marquis and Marchioness of Lansdowne. It was the former to whom the Austens applied to lease the property on Castle Square, across from the home the Marquis had created for himself: a gothic castle newly completed in 1805—although the Marquis could not resist continuing to add more and more turrets to the construction. The Austens lived in a large tenement property with a garden that was the envy of their neighbours. The house and garden looked out over the medieval town walls down to the water, where the bathing establishments were laid out. It had a wonderful view across the bay to the New Forest, a view painted by the many artists drawn to the town, such as John Constable, who spent his honeymoon there. There was still work to be undertaken to make the house ready: Frank made fringes for the curtains, and Jane noted in a letter to her sister that “I shd like to have all the 5 Beds completed by the end of [the week].—There will then be the Window-Curtains, sofa-cover, & a carpet to be altered” (8–9 February 1807). The Marquis loaned them the use of his domestic painter, Mr. Husket, to help decorate. The house was large enough for the Austens to entertain visits from Jane’s brothers and their families and to host social gatherings with card playing, reading, and music. Jane hired a piano, which is recorded in her accounts for 1808.

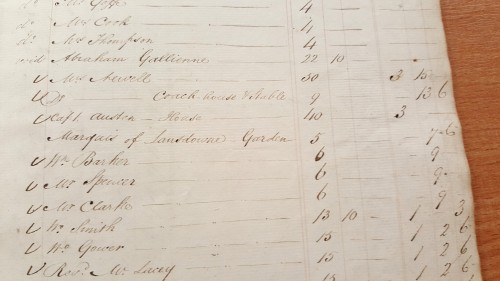

Ratebook showing entry for Francis Austen’s property. Southampton Archives SC AG8 6, Rate Book 1806–1808 All Saints. (Click here to see a larger version.)

The property was rated (for tax purposes) at £40; their neighbor Ann Newell’s house was rated a little higher at £50 plus £9 for her coach-house and stable. The widowed Mrs. Newell had moved to Southampton after the death of her husband; she owned two plantations in Jamaica, which she managed alongside her daughter Ann and Ann’s husband, the Reverend Hugh Hill of Holy Rood Church (who also made visits to the Austens). There were great changes about to take place that concerned West Indian families like the Newells and the Austens’ dear friend Mrs. Duer, who had estates in Dominica and Antigua. In 1807 the slave trade was abolished, although the owning of slaves was allowed to continue until 1834. Much of the wealth coming into Southampton came from sugar plantations, and there were so many plantation families in prominent positions that the town was described as ruled by “the West Indian party.” Several of the plantation families, such as the Gunthorpes, lived close to the Austens and are mentioned in Jane Austen’s letters.

Landsdowne Castle with the Austen house in the foreground (c.1809), by Tobias Young. Southampton Maritime and Local Heritage Collection.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

A number of artists moved to Southampton to ply their trade, painting views of the town and its surroundings that they could sell to new residents, especially those who were building villas around the outskirts of the town. These newly wealthy families did not live on vast estates with lofty rooms to display huge paintings, but they could afford substantial pieces to display in their drawing rooms. The Lewin family of Southampton paid 14 guineas for two oil paintings of the view of their property, Ridgway. The artist they employed was Tobias Young. Young had begun his career painting scenery for Lord Barrymore’s private theatre and moved to Southampton after his patron’s early death, in 1793. Young lived in a rented property in a new development called Hanover Buildings, constructed by Walter Taylor, a local engineer and entrepreneur, whose fortune came from making wooden blocks for the navy. After Taylor’s death, his widow wished to sell the property and offered it to Young, but the artist could not afford it. Harriet Austen, sister of Elizabeth Butler Harrison, who had moved to Southampton after the death of their father, was lodging with Young and his family. She stepped in with £200 and bought the residence.1 Harriet was a frequent visitor to Castle Square and was particularly close with Cassandra. Jane wrote to her sister, “Happy Mrs Harrison & Miss Austen!—You seem to be always calling on them” (20–22 June 1808).

It is likely that the cousins knew the artist and would have seen his work on show in the houses they visited. If they called at the castle, they could also have viewed the art collection of the Marquis, which included a stained-glass window panel of George III seated on a throne; a picture of the French Revolutionary leader Marat, one of Lansdowne’s “Worthies;”2 a painting of Bonaparte as First Consul; a painting of John Philpot Curran, an Irish orator, politician, and lawyer; and a bust of Bonaparte’s Marshal André Masséna. Lansdowne also commissioned the statue of George III that still stands on the south side of Bargate.

Three or four families

The Butler Harrisons

|

|

|

John Butler Harrison II and Elizabeth Butler Harrison, The Red Book. |

|

The Butler Harrisons were an important family in Southampton, a family to whom the Austens were related, and a family whose connections and networks would be useful particularly to Francis Austen. Elizabeth Austen was from a clerical family, like Jane’s; her father, Henry, was a clergyman and cousin to Jane’s father. Jane Austen had slipped down the social scale after her father’s death had left his widow and daughters in straitened circumstances; Elizabeth had also seen her place in society threatened when her father left the Anglican community and became a Unitarian. When Henry gave up his living, the family lost their home; they were rescued by Elizabeth’s mother’s relations, who gave the family a home in Tonbridge. (Elizabeth remained an Anglican, but her sister Harriet also became a Unitarian.)

Elizabeth had a limited income, but on a visit to Steventon, Chawton, and Southampton in 1786, she met John Butler Harrison II, whom she married. John had inherited £2,000 plus his estate at Amery from his father and £1,500 from his grandfather, Robert Ballard senior. At the time of his marriage, John sold his Amery estate to build a new house in Southampton. He was a successful wine merchant. (In the 1790s the Universal British Directory commended Southampton on having “many opulent wine merchants” [455].) John also ascended the political ladder in Southampton, serving twice as mayor, in 1794 and 1811.

John Butler Harrison II had a very tragic start to his life, in which the scourge of the age, smallpox, played a major role. His father, John Butler Harrison I, a member of the Hampshire Militia, lost his first wife after she gave birth to a daughter. John Butler Harrison I died of smallpox a few weeks before the birth of his son, John Butler II, by his second wife—who died of smallpox a few days after. John was brought up by his mother’s relations, the Ballards of Southampton. A portrait of John Butler Harrison I in his militia uniform has been carefully preserved by the family, and his militia hat was donated to Southampton Museums.

John Butler Harrison I in militia uniform, The Red Book. Butler Harrison Archive, Southampton Archives DZ676 1–4. |

Militia Cap of John Butler Harrison I. Southampton Museums Collection. |

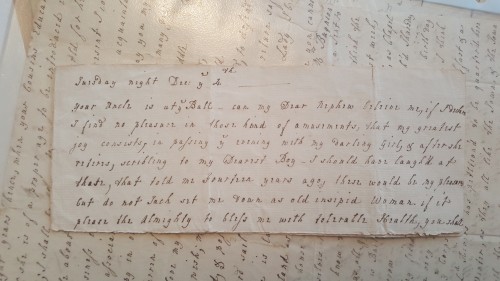

John Butler Harrison II’s uncle Robert Ballard, newly married to Melicent, the daughter of his business partner Lenard Cropp, took in the young baby. John’s sister, Elizabeth Goring Butler Harrison, was brought up by their father’s sister, Jane, who had married the rector of Chawton, John Hinton. The Ballards had lost both their own boys when they were young and had only one other child, a daughter known as Milly. They treated John as their surrogate son. As part of his education, John was sent to school in Lausanne, and in letters he begged his aunt to keep him informed of all the gossip in Southampton. These letters survive, and some samples dating from the early 1780s give a sparkling insight into the town that Jane Austen had visited in 1783. Tragically, while John was away at school, Melicent Ballard died in the same outbreak of fever that Jane and Cassandra caught while in the town as children. Melicent’s beloved nephew finished his studies in 1784.

Letter from Melicent Ballard to John Butler Harrison II.

Courtesy of Malcom and Tamsyn Barton. (Click here to see a larger version.)

On their marriage, Elizabeth and John moved into the newly built property in the parish of St. Mary’s. Elizabeth bought one very useful item with her, inherited from Elizabeth Weller, the great-grandmother she and Jane Austen shared: a household book. The book is full of handwritten recipes and useful household hints, many donated by members of the wider Austen family. Most of the entries in the first half of the book naturally date from Elizabeth Weller’s time. The book descended via the female line to Elizabeth Butler Harrison, and during her ownership she added the next largest number of recipes. This household book is similar to the one that Martha Lloyd compiled, but this collection of recipes includes the names of those who donated them.

| (Click on each image to see a larger version.) | ||

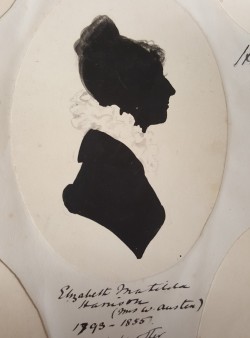

Elizabeth Matilda Butler Harrison, The Red Book. Butler Harrison Archive, Southampton Archives DZ676 1–4.

Elizabeth’s household book contains over 205 entries, many very clearly written. Topics range from the culinary to the medicinal; household items include a cosmetic recipe for coloring red or grey hair. Medical recipes include one for palsey water, which was either drunk or bathed in, and a recipe that does not specify its medical use but that should be taken at the “change and flush” of the moon. Some recipes call for unusual ingredients: one begins, “Take Dragons.” There are also recipes for “stump pye.” Household hints include a liquor for boots and shoes, mahogany coloring for furniture, and a cleaning product for grates, plus information on making ink and poison and dyeing gauze. There are several recipes for the bite of a mad dog—in fact, a cure for dog bites was a major promotion by the watering place of Southampton. Many recipes show the influences of colonization and empire. There are recipes for sugar cakes (sugar being a major import from the West Indian plantations), Portingall cake, curries, and punches made fashionable thanks to the East India Company.

The Butler Harrisons had ten children, who all lived to adulthood. Silhouettes of Elizabeth, John, and their children were in the collection of their great-grand-daughter Helena Austen Harrison, which was donated to the Southampton Archives. The image of Elizabeth Matilda, Jane Austen’s goddaughter, was prominently displayed in the exhibition. In 1814 Elizabeth Matilda married her cousin the Reverend William Austen in St. Mary’s Church, Southampton. Jane’s mother wrote to her granddaughter Anna Lefroy about the generous distribution of Bride-Cake (Govas 35). The couple traveled into Sussex, where William was the incumbent of Horsted Keynes.

John Butler Harrison II in old age. Courtesy of Colin Hyde Harrison. |

Elizabeth Butler Harrison in old age. Courtesy of Colin Hyde Harrison. |

Elizabeth and John Butler Harrison lived long lives, and their images were later captured in photographs. When they died, they were buried in the churchyard at the Jesus Chapel, St. Mary Extra, on Peartree Green—a chapel very popular with the East India Company families and other wealthy residents who lived on the high ground around Peartree, with its panoramic views over Southampton.

John Sturdy’s journal exhibit.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Throughout Austen’s life Britain was in a constant state of war—particularly the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars with France—and Southampton was on the front line. John Butler Harrison II had numerous responsibilities in the town, including becoming an officer in the company of Loyal Volunteers. The company was founded in 1796 in response to the government’s inviting gentlemen to come forward to form volunteer infantry and yeomanry cavalry.

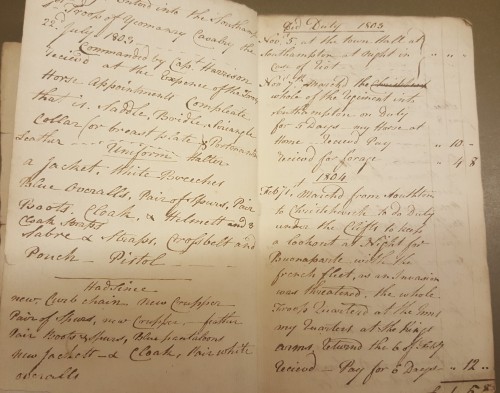

Serving with Butler Harrison in the years 1803–09 was local auctioneer John Sturdy. He also lived near the Austens in a property a few minutes’ walk away, on St. Michael’s Square. Sturdy kept a journal of the Loyal Volunteers’ activities, and when he left the service in 1809, he donated the journal to his captain, John Butler Harrison II.

The journal begins in 1803, the year the militia was put back onto a wartime footing after a brief respite in the Napoleonic War following the Treaty of Amiens. The Loyal Southampton Fusiliers were under the command of Josias Jackson of Bellevue House, who had recently settled in the town. Josias Jackson was heir to five plantations on St. Vincent and had taken part in the Second Carib War (1795). In 1807 he became MP for the town and in 1812 made a speech in Parliament praising “the character of the West Indian planters,” who, he said, “in accomplishments and humanity were equal to the most polished society of England” (Thorne 3: 290).

John Sturdy’s section, the South Hants Yeomanry Southampton troop regiment, was based on the model of the Light Horse Volunteers (raised in London in 1779). They were armed as Dragoons, traditionally mounted infantry. The company’s first officers were Colonel George Henry Rose, Esq., a leading politician, member of the West Indian party, and MP for Southampton in 1794 and 1800; Captain William Smith, Esq., who was Collector of Customs for the port and served twice as mayor; and Lieutenant John Butler Harrison II, Esq.

John Sturdy's journal, detail. Courtesy of Colin Hyde Harrison.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Sturdy’s journal records troop reviews, exercises, and drills. In December 1803 almost 2,000 local volunteers were reviewed on Shirely Common by the Duke of Cumberland, Prince Ernest Augustus, fifth son of George III and later King of Hanover. As fears of invasion grew, the next spring saw an exercise in which volunteers from Southampton and other areas staged a mock attack on Peartree Green from the River Itchen. In February 1804, as concerns about a French invasion grew, Sturdy’s troop spent six days in Christchurch keeping a lookout for the French fleet before returning to Southampton. They undertook drills in South Stoneham, Redbridge, Nursling, and Millbrook. Late in December 1804 Napoleon Bonaparte was crowned Emperor, so the troops marched with a fife to St. Lawrence Church, where the Reverend Mears, the troop chaplain, preached a sermon: “Put on the whole Armour of God that ye may be able to stand against the wiles of the Devil.” In 1805 on the 8th anniversary of the Yeoman Cavalry’s founding, a celebratory dinner for the officers was held at the Crown Inn on the High Street.

In a journal entry for June 1808, Sturdy writes of the generosity of Captain Harrison.

June 1st 1808 Wednesday 2 OClock P.M. The 1st Southampton Troop mett at the Dolphins Inn to dine and spend the fines collected during the Last 10 Days—which amounted to something handsome and Capt Harrison with his usual Liberality made a present of Two Guineas to the Troop—the Day was spent with great Harmony & good Humor—Mr Major the Quarter Master Presided at Table & Sergt Rogers vice President, Capt H came after Dinner took a Glass of wine with us and Departed N.B. the following Toasts were Given King, Queen and royal family Navy & Army, Colonel Murry, The officer, Noncommission Officers and privates, of the Regiment of Yeoman cavalry, our Worthy Capt. Harrison, may Nelsons Motto never be erased from an Englishmans Breast

The Dolphin was an important inn for social gatherings and assembly balls, and the troops spent as much time enjoying dinners there as they did parading.

The Middletons

Anne Morse Middleton (at harpsichord), The Morse & Cator Family (c. 1784), by Johann Zoffany. Aberdeen City Council Art Gallery & Museums Collection.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Nathaniel Middleton was the brother of John Middleton, who was on two occasions tenant of the Great House in Chawton. Nathaniel had joined the East India Company and, as a senior member of Warren Hastings’s administration, had a successful career. He was later called to give evidence in Hastings’s trial in the House of Lords. Middleton’s lack of recall about events in India earned him the nickname “Memory Middleton.” In India in 1780, Nathaniel Middleton married Anne Morse. Anne had been born in Jamaica, one of six children born to the plantation owner John Morse and his mistress, Elizabeth Augier aka Tyndall, who was a descendant of slaves. One of the children, Roger, died in Jamaica; Morse sent the other five to England to further their education and prospects. In England, Catherine married her father’s English attorney Edmund Green, and John served in the Horse Guards and managed his father’s estate at Midanbury. Robert, Sarah, and Anne, however, traveled on to India. The painting of the Morse siblings shows Robert playing the cello and Sarah in the background with her new husband, the East India Company man William Cator, on the right. In the center Anne plays the harpsichord; her shoes are adorned with diamonds that papers later reported were worth £35,000.

In 1784 Anne and Nathaniel Middleton moved back to England and built a villa on the outskirts of Southampton, Townhill Park House, adjacent to Midanbury House, the property owned by Anne’s father. Their home was full of Persian art, including sixty-two drawings illustrating the costumes of India and portraits of the Emperor Jehan and Shuja ud-Daula, the latter having presented the collection to Middleton. The family, however, were soon to find themselves splashed across the newspapers. Not only were there the headlines from the Hastings trial, but another, more personal trial was about to begin. Anne’s father died in 1780 and divided his fortune among his illegitimate children. Jamaican law at the time stipulated that mixed-race children could not inherit more than £2,000, and Morse’s white nephew Edward went to court to stake his claim for the Morse fortune. Sarah’s husband acted as attorney for his wife’s family, with the case rumbling on until 1799. It was eventually successful for Morse’s children primarily, as the children’s grandmother had previously gone to court to have her children declared white. When Middleton was asked if he knew about his wife’s background, he replied that he had no knowledge and found it “an entire strangeness”; he further claimed that, as he had resided in India, he had never been informed of her family background (Morning Herald July 1786).

The Middletons had a long and happy marriage, producing ten children. In his will Nathaniel asked his wife to also look after his illegitimate children. He had had a mistress in India and with her had three children: Henry George, Elizabeth, and Catherine. Although he had left each of them £10,000 in his will, unfortunately much of the Middleton fortune was lost in the failure of a bank in which Nathaniel was a partner. Of these children, Henry George appears to have died young; Elizabeth married an extremely wealthy East India Company merchant; and Catherine married a less successful Company man (so in her will Anne left her £5,000 in trust).

The Fitzhugh/Lances

William Fitzhugh and David Lance were young men who made their fortunes in China as super-cargoes for the East India Company. They became business partners for projects additional to their Company work and eventually became brothers-in-law when David Lance married William’s sister, Mary. Mary Fitzhugh, along with her brothers William and Valentine, were born in Constantinople. Their mother was a member of the refugee Huguenot community, and their father worked for the Levant Company. When the family left Constantinople, they, on the advice of the British Ambassador, moved to Southampton, where Mary met David Lance.

Chessel House, by Tobias Young. Southampton Museums & Art Gallery.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

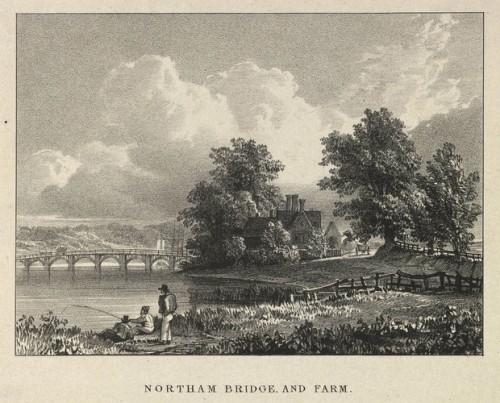

The newly married Lances lived in Above Bar. They built Chessel House, a villa on the east of the River Itchen, with picturesque views over the water to Southampton and grounds landscaped in the style of Repton. Jane thought nothing of traveling from Castle Square to Chessel House and back, a circular five-mile trip.

Martha & I made use of the very favourable state of yesterday for walking, to pay our duty at Chiswell—we found Mrs Lance at home & alone, & sat out three other Ladies who soon came in.—We went by the Ferry, & returned by the Bridge, & were scarcely at all fatigued. (9 December 1808)

The bridge over the River Itchen was a new addition, the building of which was led by investors, including David Lance, in 1796, the same year he was building his villa.

Northam Bridge, and Farm, by an unknown artist. The Royal Collection.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Jane Austen made more than one visit to Chessel and took tea there, which would have been served on the Fitzhugh porcelain commissioned by William Fitzhugh while in China. The porcelain design was dominated by flowers and objects representing the Chinese Four Treasures or Accomplishments: a lyre-case, chequers board, calligraphy, and books. The design also incorporated dragons (regarded as lords of the heavens and seas) and the traditional Buddhist emblem of the pomegranate. In the early nineteenth century, the pattern was taken up by the Spode factory. David Lance advised collectors of porcelain, such as Sir Joseph Banks’s wife, Dorothea, who produced a Dairy Book on old china. David Lance also brought back China tea and was fond of hyson, which could have been what the Austens were served.

|

|

|

Fitzhugh porcelain. Courtesy of Dirk Fitzhugh. |

|

Prior to her move to Chawton in 1809, Jane Austen attended a ball at the Dolphin. The Lances were in attendance, along with their daughters Mary and Emma. Jane may have been thinking about another Emma—Emma Watson or even Emma Woodhouse—when she wrote,

The room was tolerably full, & there were perhaps thirty couple of Dancers;—the melancholy part was to see so many dozen young Women standing by without partners. . . . We paid an additional shilling for our Tea, which we took as we chose in an adjoining, & very comfortable room.—There were only 4 dances, & it went to my heart that the Miss Lances (one of them too named Emma!) should have partners only for two. (9 December 1808)

Emma Lance died of consumption in 1810, and the Lances moved to London in 1817. After the death of her husband in 1820, Mary Lance moved to Paris.

Mary Lance’s brother William Fitzhugh married Charlotte Hamilton. The couple were supporters of the arts. William was a gifted painter and exhibited his work at the Royal Academy. He painted a view of Bannisters, their marital home.

Bannister House, by William Fitzhugh. Courtesy of Dirk Fitzhugh.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Mrs. Siddons (1804), by T. E. Lawrence. Courtesy of Tate Britain.

Charlotte was a very close friend of the actress Sarah Siddons, and in 1804 she commissioned Thomas Lawrence to produce a painting of the actress. Mrs. Siddons sat for Lawrence by candlelight in March and April 1804. On 4 August, Lawrence wrote to Mrs. Fitzhugh asking for permission to make two small copies before delivering the picture, one for a print to match that of Mrs. Siddons’s brother John Philip Kemble as Hamlet. Mrs. Siddons is pictured standing, dressed in a black velvet gown with her hand turning the page of the open book. In an engraving made by Say, the title of the open book is given as Paradise Lost. On the spine of the closed book beneath is “Otway,” a reference to Mrs. Siddons’s performances as Belvidera in Thomas Otway’s Venice Preserved, a part she had first played in 1777. What appears to be a monument on the right is inscribed “Shakspere.” Mrs. Siddons was renowned for her portrayal of Shakespeare’s tragic heroines. Although Mrs. Siddons’s niece, Fanny Kemble, felt the painting made her look like “a handsome dark cow in a coral necklace” (Kemble 452), Siddons said that it was more like her “than anything that has been done” (Kennard 307). The painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1804. Joseph Farington, a member of the Academy, reported that on 30 April at 12 “the doors were opened—Mrs. Siddons and Mrs. Fitzhugh came, the latter was not satisfied with the likeness of the portrait of Mrs. Siddons” (Fitzhugh 628). Despite Charlotte’s disappointment, the portrait was hung in the Bannisters’ dining room, and Fanny Kemble remembered sitting under it on a visit to comical old “Mrs. F— —, a not very judicious person” (Kemble 10).

Mrs. Siddons made regular visits to Bannisters, and it was no doubt this link with Charlotte Fitzhugh that led to Mrs. Siddons’s performing in the theatre in Southampton on more than one occasion. In October 1801 the Hampshire Chronicle published an advertisement for the penultimate night of her appearances in that season. On Monday 12 October she performed in the tragedy of Douglas as Lady Randolph, and on Wednesday 14 October as Mrs. Beverley in the tragedy The Gamester. She returned in 1809:

The Managers of the Theatre ever anxious to exert themselves in the best possible way to procure novelty and amusement beg leave most respectfully to inform the public that they feel great pleasure in announcing the engagement of that great and inimitable actress Mrs. SIDDONS, the unrivalled Melpomene of the British stage who will make her first appearance on Wednesday Evening next in the interesting and affecting character of Mrs. Beverley, play of the Gamester. The other nights of her performance will be Friday the 6th, Monday the 9th and Wednesday the 11th of October in three of her favourite and most popular characters.

There is no evidence that Jane Austen saw Mrs. Siddons perform in Southampton or was introduced to her by Charlotte Fitzhugh, although it would have been the best opportunity for her to meet the woman who was said to be her favorite actor.

The French Street Theatre, Southampton (1805). Printed by T. Woodfall.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

Henry Fitzhugh.

Courtesy of Dirk Fitzhugh.

(Click here to see a larger version.)

The Fitzhughs had four children, William, Sophia, Henry, and Emily. Sophia died at thirteen, and in the same month of 1808, they lost their twelve-year-old son, Henry. A pupil at Winchester College in 1807, the boy had transferred to the Royal Navy. He was only eleven when he joined the service and should not have begun his qualifying period as a midshipman until he was thirteen. On 16 May 16 1808 he was killed in action at the battle of Alvoen while serving as a midshipman on HMS Tartar, alongside his twenty-three-year-old captain, George Edmund Byron Bettesworth, cousin of Lord Byron: “Among the first shots was one that killed Capt. Bettesworth while he was in the act of pointing a gun: and Mr. Henry Fitzburgh, a fine and promising young Midshipman, fell dead nearby at the same instant” (James 35).

Jane Austen left Southampton for Chawton in 1809. After the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the glory days of the watering place and spa of Southampton were drawing to a close, and by 1815 the town was not attracting the gentry and retired naval and army officers that it once had. As for our featured families, Nathaniel Middleton died in 1807, and his wife lived her later days under medical care in London; Ann Newell died in 1814; and the Lances moved to London in 1817. Only the Butler Harrisons and the Fitzhughs maintained their homes in Southampton. The events of 1815 ushered in peace and the chance to travel abroad, and by 1830 Southampton had reverted to its former existence as a premier port, helped in no small part by William Fitzhugh and his investment in steam ships and railways.

The High Street, Southampton, from All Saints Church (1828), by Louise Haghe.

Printed by William Day. (Click here to see a larger version.)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to Malcolm and Tamsyn Barton; Colin Hyde Harrison; Dirk Fitzhugh; Jo Smith and the Southampton Archives; Maria Newbury and Dan Matthews; Southampton Museums and Art Gallery; Aberdeen Archives; Gallery and Museum; and the Tate Gallery.

NOTES

1See Lease of Harriet Austen, Correspondence, and Harriet Austen Property.

2After a visit in 1811, Lady Bessborough in a letter 24 Oct 1811 quoted Lady Lansdowne’s on Lord Lansdowne’s Worthies (Leveson Gower 2: 410).