In Jane Austen’s Love and Freindship, Gustavus says that his mother Bertha and aunt Agatha “‘could neither of them exactly ascertain who were our Fathers; though it is generally beleived that Philander, is the son of one Philip Jones a Bricklayer and that my Father was Gregory Staves a Staymaker of Edinburgh’” (138). A bricklayer’s vocation is still understandable to us today, but in the twenty-first century, staymakers are not so common. These artisans produced stays, sometimes called a pair of stays, which are fully boned, and laced bodices worn under clothes to support and shape the body. The history of staymaking and its place in Georgian fashion and society, the changes in the design of stays and corsets during Austen’s lifetime, and the portrayal of stays in the era’s print culture shed light on the references to stays in Austen’s letters and the inclusion of a staymaker in her juvenilia.

![]()

In his General Description of Trades published in 1747, T. Waller explains that stays were “principally made by men, though both Women and Men work on them, and the Work may very well be called a Branch of Tayloring” (qtd. in Sorge 17). Staymakers were one type of skilled artisan employed in the business of making garments. Tailors made men’s and women’s clothing, and in the late seventeenth century the latter task was taken up by female mantua-makers, later called dressmakers. Although it was a specialized and highly skilled trade, in general staymakers were not as affluent as tailors because stays were less expensive than men’s clothing (Sorge-English 60).

Staymakers and retailers were located in small towns and in larger cities like Canterbury and Edinburgh. In a letter of 1813, Jane Austen wrote that “[t]he two Fannies” took Edward’s daughters Louisa and Cassandra Jane to Canterbury to try on new stays (18–21 October 1813).1 Edinburgh is where Austen’s Gregory Staves lived, and eighteenth-century legal documents show that staymakers were located in the Canon-gate area of that city.2 Establishments varied in size, from those owned by a master staymaker with numerous apprentices and journeymen, to a solitary staymaker renting out a room and living hand-to-mouth (Sorge-English 67).

Staymakers could operate out of their workshops or could go to upper-class clients’ homes to take their body measurements and to conduct the fittings.3 They used the measurements to create a pattern with which to cut the individual sections of the stays. In the eighteenth century, stays were composed of multiple layers of fabric: the external layer could be made from a simple plain-woven linen or a complex brocade; inner layers were usually heavy linen; and the lining was often a lighter linen.4 Channels for “bones,” or stiffening material, were sewn through the layers. Trade cards of the era advertise stays with bones made from reed, pack thread (a strong and thick type of twine), straw, and, most commonly, whalebone.5 All of these materials were light and incredibly flexible and in time would mold to the body’s shape. To finish the stays, the sections were sewn together and eyelets for lacing were sewn in.6

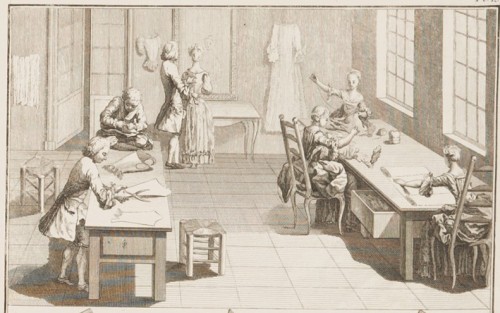

A common myth held that forcing the bones into the channels sewn into the fabric took great strength and could therefore only be accomplished by men, and for this reason staymaking was a male trade for most of the eighteenth century. It does not take any great strength, however, to push a bone into a properly sewn channel; it is more likely that the misconception was promulgated to hide the fact that during much of the eighteenth century women were not permitted to be members of guilds or allowed to be acknowledged business owners. Even so, a great deal of the stitching was done by female seamstresses in the workshop. The division of labor depicted in this French print (Figure 1) is probably similar to what took place in English staymakers’ studios (Sorge 21).

Figure 1. François Alexandre Pierre de Garsault II. Staymaker’s Studio (1769).

(Click here to view a larger version.)

(The information for each figure is located after the Notes section.)

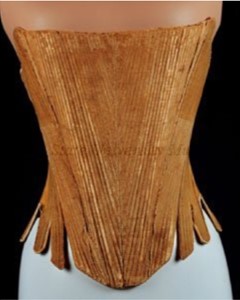

During the years of Austen’s early life, stays created a pleasing cylindrical shape in which the body was encased in a series of bones, sometimes as many as sixty, sewn next to each other (Figure 2).7 A busk—a piece of wood, whalebone, or metal slipped into the stays at the center front—kept the front of the stays straight and upright. The pattern of the stays was cut not to constrict the waist, but to create a slight cone. The bust was held firmly but not uncomfortably, thus creating a uniform line where clothing was worn. A bell-shaped petticoat’s circumference of 135 to 140 inches further enhanced the illusion of a small waist. Women of the 1770s wore gowns that were made from copious amounts of luxurious fabric and that had form-fitting bodices that emphasized a mono-bosom and natural waist (Figure 3). Noticeable mounds of bosom may or may not have been covered with a kerchief, depending on the time of day and social situation.

Figure 2. Quilted cotton, tan leather, baleen boning (c. 1770–1790). |

Figure 3. Robe à la française with Attached Stomacher and Matching Petticoat (c. 1770–1780). |

There were perceptions that wearing stays could be uncomfortable due to their unyielding form and that the shape they created was unnatural. In 1778, Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, wrote in her novel, The Sylph

poor Winifred, who was reduced to be my gentlewoman’s gentlewoman, broke two laces in endeavouring to draw my new French stays close. You know I am naturally small at bottom. But now you might literally span me. . . . Then, they are so intolerably wide across the breast, that my arms are absolutely sore with them; and my sides so pinched!—But it is the “ton”; and pride feels no pain. It is with these sentiments the ladies of the present age heal their wounds; to be admired, is a sufficient balsam. (qtd. in Waugh 68)

A poem published in London Magazine in 1777 warned husbands about their fashionably dressed wives:

Thus finish’d in taste, while on Chloe you gaze,

You may take the dear charmer for life;

But never undress her—for, out of her stays,

You'll find you have lost half your wife. (qtd. in Waugh 67)

These concepts were illustrated in the recurring print motif of tight lacing, which alluded to the excessive pride and vanity shown by fashion-obsessed, social-climbing, or elderly women who engaged in the practice.8 In John Collet’s Tight Lacing, or Fashion Before Ease (Figure 4), it takes the strength of a woman’s husband, her maid, and a page-boy to pull her stay laces tight while she holds onto the bed for stability. Her pet monkey points at a book with the text, “Fashions Victim a Satire.” Tight Lacing, or, The Cobler’s Wife in the Fashion (Figure 5), a print of 1777 by William Hitchcock, shows not only the foolishness of fashion but of dressing above one’s station in life: a cobbler’s wife, though dressed in stylish accessories, is too poor to have a lady’s maid, so she uses one of her husband’s tools as a weight to pull her stay laces tight.9 Another etching of 1777 entitled Tight Lacing (Figure 6) shows an old and unattractive woman using a poker to help her pull tight the stay laces of a crone who has aspirations to fashionable dress.

During the forty-year period of Austen’s life, changes came to the silhouette of fashionable dress, and underneath it all, the shape of stays and the materials from which they were made altered. A new, much more casual style of dress was popularized in the 1780s by the French queen Marie Antoinette (Figure 7). The robe de gaulle (also known as the chemise à la reine) was a simple gown made of delicate Indian muslin that was belted around the waist with a sash. The breast was emphasized by large ruffles attached to the neckline and the addition of a fine muslin or gauze kerchief.

Figure 10. Silk damask, lined with linen, reinforced with whalebone, hand-sewn (1770–1790).

Stays were an additional aid to this prow-shaped look; a wider center front piece was created, and straps were set at the edge of the armhole. There were several other construction methods that led to the full and broad shape. A fully boned pair of stays with the front bones set at eighty degrees easily creates a prow-front look (Figure 8). If one preferred fewer bones, a trellis style of vertical and horizontal bones could be used (Figure 9), or horizontal bones could be set at the top of the bust line (Figure 10).

Figure 8. Linen, wood, leather (1785–1795). |

Figure 11. Silk taffeta, lined with silk, ribbon (1780s).

(Click here to see a larger version.)

A completely different underpinning option in the 1780s was an unboned silk bodice that was cut like stays (Figure 11).10 At the same time, the garment’s name began to shift from “stays” to “corset.” In 1785, The Ladies Magazine reported that “French ladies . . . never wear anything more than a quilted waistcoat, which is called un corset, without any kind of stiffening” (qtd. in Mactaggart and Mactaggart 46), and several staymakers in London advertised “Corsets a la Francois” (46). The mantua maker Mrs. Mayer described herself in 1789 as “the only maker of French stays and Circassian Corsets” (46).11 As Peter Mactaggart and Ann Mactaggart have suggested, it is not surprising that as lighter stays with little or no whaleboning came into fashion, women could begin to produce stays. Since women had long been involved as seamstresses in the stitching of stays and had witnessed them being produced, it would not have been difficult for women to gradually take over their creation (Sorge-English 20–21). By the turn of the century, stays and corsets were listed in the offerings of ladies’ dressmakers, who were women. Rudderforth’s advertised that women would be waited on by “experienced Females,” not men, indicating an important shift both in who created the stays and in who saw to their fit.

The muslin gown of the 1780s was superseded in the next decade by the even more simple Neoclassical gown. Influenced by women’s desire to look like statues draped in white, the trend was led by Emma Hart (later Lady Hamilton). During her living statue performances, called “Attitudes,” she draped herself like the women in the paintings found in Pompeii (Figure 12), and, as a leader of fashion in Naples society, she wore Greco-Roman styles both on stage and off.12 Under the influence of classical statuary, the waistline of gowns settled just under the bust, and skirts narrowed to a hem circumference of a slender 72 to 96 inches (Figure 13); this columnar shape was to last through the 1810s.

The Neoclassical gown emphasized the beauty of the body’s natural lines, and in response the 1790s was an era of incredible invention and re-interpretation of bust support. While fashion history texts lead us to believe that everyone threw away their corsets during this time, the truth is much more interesting. Very few women who grew up wearing stays were comfortable abandoning them all together, and even fewer had the body and the daring to go all but bare breasted. The new fad for the natural look created stays that had V-shaped gores (inserted sections), half-circular gores, or gathered sections, all of which allowed the bosom to be two separate entities instead of the mono-bosom that had dominated most of the eighteenth century. The waistline of corsets rose to match the outer garment, but they often retained the tabs of an earlier style. Some had light boning, and other styles maintained the high boned back (Figures 14 and 15).

Figure 14. Hand-stitched cotton, with baleen boning (c. 1805). |

Figure 15. Cotton with silk embroidery, boning, and lined with linen (c. 1790). |

While many embraced the new high waistlines and more simplified corsets, there were likely many who were not completely comfortable with a bosom that jiggled. One of the easiest ways to date dresses from the late 1790s to about 1810 is that many had a new type of construction that included a separate linen section that pinned or laced in the front. This linen band held in the bosom and added an additional layer before the fashion fabric was gathered over the top (Figure 16). In the late 1790s other fast fads centered on sleeveless short vests, corselets worn on the outside, and the newest clothing craze, the Canezou in France (Figure 17) and the Spencer in England (Figure 18). These were all secondary layers worn on the exterior to hide or support the new bosom.

As the terminology fully transitioned from stays to corsets in the early 1800s, there was a huge variety of seemingly one-of-a-kind corset styles and major changes in construction. Corsets, made from linen and cotton and later cotton alone, were either single-layer or double-layer construction, not four or five layers like the earlier stays. Many had no bones at all, some laced in front and others in the back, and some mirrored the construction of dress bodices, like Elizabeth Bonaparte’s 1803 corset (Figure 19) in the collection of the Maryland Historical Society.

Retailers such as Rudderforth’s Warehouse provided numerous styles from which to choose, including “French, English, & Italian” (Figure 20), and they even advertised Elastic Belts and Elastic Gore Stays made from wire springs.13 What is not advertised is the whole concept of freedom of movement and flexibility, which was the hallmark of the Neoclassical movement that had begun a decade earlier and which had now become the norm. These concepts are manifested in stays that were meant to be worn under, not over, the bust (Figure 21).

Figure 21. Homespun tan linen, boning, deer skin (c. 1800). |

Around 1810 all of the different styles seem to coalesce into a two-layer corset that maintained the use of the busk, now curved to her individual figure, and stiffened with cording (lengths of twisted linen or cotton) instead of whalebone. A fashion plate from 1810 (Figure 22) introduces hip gussets, or inserted panels. Another style was the princess seam cut, with long panels, no join or separation at the waist, and no gussets or gores. This style began as a single layer (Figure 23) and developed into a two-layered, corded corset with a variety of individual cording patterns (Figure 24).14 Thus, during Austen’s lifetime, fully boned stays that created a conical, mono-bosom shape transitioned to lightly stiffened corsets that delineated the breasts as two distinct units.

Figure 23. Princess seam soft corset. |

Figure 24. Cotton, bone (1820–1830). |

![]()

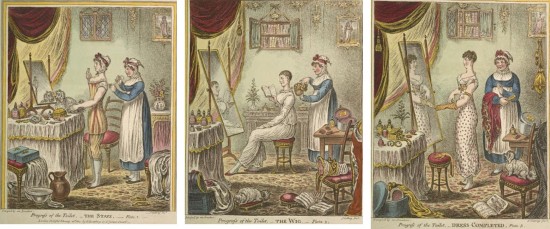

The opinions of Austen’s contemporaries about the effects of wearing stays and corsets that elevated the breasts are made known in periodicals and satirical prints. A writer for the Morning Herald in the 1790s said, “The bosom, which Nature planted at the bottom of her chest, is pushed up by means of wadding and whalebone to a station so near her chin that in a very full subject that feature is sometimes lost between the invading mounds” (qtd. in Waugh 72). A print of 1799, The Virgin Shape Warehouse, illustrates a show room of various kinds of underpinnings, including “favourite & accommodating Circassian Vests, alias Bosom Friends, which permits free respiration, prevents all pressure on the chest, raises the languid Breast to the appearance of a Juvenile heaving Bosom” (Figure 25). In 1811, “A Lady of Distinction” described a “bosom shoved up to the chin, making a sort of fleshy shelf” (qtd. in Davidson 66). In a series of prints called The Progress of the Toilet (Figure 26), the exposed and elevated chest of the woman who is being dressed by her maid is on full view.

Austen joined in the critique of this exaggerated voluptuousness in letters to her sister, Cassandra. In 1801, Jane described a Miss Langley, who “is like any other short girl with a broad nose & wide mouth, fashionable dress, & exposed bosom” (12–13 May 1801). In 1813, she was relieved to write that “I learnt from Mrs Tickars’s young Lady, to my high amusement, that the stays now are not made to force the Bosom up at all;—that was a very unbecoming, unnatural fashion” (15–16 September 1813).

Such were the views of Austen and her contemporaries in the early 1800s, but how were stays perceived when Austen included the character of a staymaker in her youthful writing? As shown above, stays were shown as instruments of pride and vanity, but eighteenth-century satirical printmakers also frequently included them as objects of eroticism. A 1773 engraving from the publication Human Passions Delineated (Figure 27) likens the act of sexual penetration to the insertion of laces into the holes of the stay, which the male figure is doing as he puts his hand into the female figure’s skirt pocket to touch her genitals (Steele 21).

William Hogarth, known as the “grandfather of satire,” produced scenes in which stays that have been removed by the female figure before lovemaking are featured prominently, thus signifying them as erotic garments. The concept of moral uprightness was the focus of eighteenth-century philosophical and religious debates, and there is a long history of interpreting an upright posture with being a virtuous human in mind and body. As Sander L. Gilman states, “Perfect bodies meant perfect posture, and that in turn meant perfect moral character” (98). Stays could be an aid to posture, and, as Valerie Steele has commented, they “functioned as a sign of respectability, because they controlled the body, and, by extension, the physical passions” (28). Satirical prints allude to this philosophy by highlighting the notion that when the stays are laid to one side, a woman’s honor is at stake. In Hogarth’s Before (Figure 28), the fact that the young woman has already removed her stays, which lie on the chair, indicates that her resistance to the man’s sexual advances is for appearance’s sake only. In the companion piece, After (Figure 29), although the man is getting dressed, the stays remain on the chair, and the woman is now the one making advances. In Plate V of Hogarth’s Marriage á la Mode (Figure 30), the abandoned stays and hoop that the woman has removed in preparing for her assignation with her lover symbolizes her dishonor (Steele 21).

Not only stays, but staymakers themselves were associated by printmakers with sexuality. Taking measurements to produce stays was an intimate business, resulting in the staymaker’s knowledge of his client’s exact size and shape, or as a print of 1784 cheekily says, her “pleasing circumference” (Figure 31). The male staymaker gazes amorously up at his client, an idea that is more lustily handled in a French print (Figure 32) in which the artisan gets a good look at his client’s cleavage.15

The keen observation and critical analysis of Georgian society that Austen demonstrates from her youthful writing onwards suggests that her reference to a staymaker in Love and Freindship draws on the affiliation of stays and their makers with eroticism. Austen seems to show a familiarity with the alluring nature of clothing in the juvenilia. Jenny McAuley has determined that in Catharine, or The Bower, Austen had originally included the word “pierrot” to describe a garment being given to the character Augusta Barlow.16 This type of jacket daringly flattered the female form and therefore alluded to ideas about the social and sexual liberation of women (McAuley 195; Figure 33). In another of her early works, A Beautiful Description of the Different Effects of Sensibility on Different Minds, the heroine Melissa “lies wrapped in a book muslin bedgown, a chambray gauze shift, and a french net nightcap” (J 92). Hilary Davidson points out that the contemporary reader would understand that these fabrics were transparent (35), and therefore Melissa is, as Austen would later describe a Mrs. Powlett as being, “nakedly dress’d” (8–9 January 1801). In Love and Freindship, Laura is undone by Edward’s death and, in a parody of King Lear’s speech, raves incoherently, “‘They told me Edward was not Dead; but they deceived me—they took him for a Cucumber—’” (130). Jillian Heydt-Stevenson wonders if, in using “cucumber,” Austen is referring to the eighteenth-century slang for tailor or if she is alluding to a phallic symbol (para. 37).17

Given the prevalence of the depiction of stays in satirical prints, Austen could have been aware of the sexual nature of the garment as represented in that medium.18 As we have shown, Georgian era staymakers were on intimate terms with their clients, and the stays themselves were regarded as erotic objects. Gregory Staves knew Gustavus’s mother so intimately that he fathered an illegitimate child with her. Gustavus’s cousin is named Philander, a term used since at least 1737 to describe a man who frequently enters into casual sexual relationships with women (“Philander”). Gustavus and Philander ironically take pride in their illegitimacy because, although their fathers had a low social status as a bricklayer and a staymaker,19 their mothers were at least half-highborn in being the daughters of a Scottish nobleman (though of course the products of his illicit relationship with an Italian opera-girl).

Love and Freindship includes numerous other examples of sexual innuendo. Heydt-Stevenson comments that the rampant illegitimacy in the family of the main character, Laura, and its ties to Italy, Spain, and France would have signified libidinousness for Austen’s English readers (para. 38). In a legally questionable arrangement, Laura’s father, who is not a man of the church, marries her to Edward, whom she has just met, enabling instant sexual gratification. There are homoerotic friendships between Edward and Augustus and between their wives Laura and Sophia, and the two women, Heydt-Stevenson points out, “fantasize sexually about others” (para. 38).

The character of Gregory Staves is an intriguing example of how artists of the era used stays and their makers as suggestive fodder, and his inclusion can be seen as part of the sexually charged word play and innuendo found in Love and Freindship and throughout Austen’s juvenilia. Examining the material culture of her time gives us greater insight into Austen’s experiences with underpinnings and with the cultural values associated with them in the Georgian era.

NOTES

1Louisa and Cassandra Jane would have been about nine and seven years old at the time. In that period, many parents felt that stays were necessary to help their children’s spines to grow straight. Young children of both sexes wore soft stays, and, as female children grew, boned stays would be made in the same fashion as adult stays. As a child in the 1770s, Jane Austen would have worn basic stays made from paste board covered in fabric.

2A list of tenants in a building in Canon-gate that was sold in 1762 included George Low, a staymaker; Lord Adam Gordon, a military officer; and Ewan, a letter carrier (Edinburgh World Heritage 3). As seen in court records, other Canon-gate staymakers were involved in Process of Scandal (or defamation) and divorce cases (Grant et al. 22, 39, 42, and 53).

3While the best stays were measured and made for an individual, there were off-the-rack stays that could be adjusted to individual shapes, as well as a thriving secondhand market from which to purchase.

4In examples that have been examined by the authors, it appears that linings were often removable for washing.

5Although the material is known as whalebone, it is actually baleen, the comb-like keratin plates in whales’ jaws.

6Extant eighteenth-century examples exhibit sewn eyelets. The nineteenth century introduced a variety of eyelet choices, including metal rings, bone rings set on the edge or inset into the fabric, and, eventually, the metal eyelet, which became standard in factory-made corsets.

7The publications by Bruna, Salen, and Shep were consulted for information about the history and shapes of stays and corsets.

8The clothing habits of vain men were not immune from being satirized. At the turn of the century, a simple and streamlined silhouette in men’s clothing, inspired by ancient sculptures of nude athletes, caused males’ contours to be on full display. The appearance of a better male physique could be achieved by corsetry and padding, and there were numerous satirical prints in the 1810s of dandies wearing tight-laced stays and other devices for body modification.

9She might have to use that tool as a weapon, as her disapproving husband raises a leather strap with which to beat her.

10This type was perhaps influenced by fashion from Circassia and Turkey and might have influenced the soft corset style that became popular ten years later. More research is planned on both matters. See note 11 below.

11Women of the Circassian people of the Northwestern Caucasus had been renowned for their beauty since the Middle Ages.

12See Rauser for an in-depth study of the Neoclassical gown.

13Rubber elastic was not invented until 1845.

14Hip gussets would become standard by the 1820s and very large by the 1830s, although the Princess seam style co-existed until the late 1840s. The basic 1810s shape, with small adjustment for size of the gussets at the bust and hip, remained in fashion until the sewing machine turned the factory-sewn corset into a cheap commodity in the late 1850s.

15According to the 1811 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue by Francis Grose, the meaning of the word “stay” is “A cuckold.” Might this association refer to the fact that a staymaker lover could “make” a cuckold out of a husband?

16The more up-to-date “Regency walking dress” replaced “pierrot” in a revision of the text.

17Cucumber Time was the slow season for tailors: “when cucumbers are in, the gentry are out of town” (Quinion).

18Austen included the scene in Persuasion of Admiral Croft and Anne Elliot conversing in front of a print shop on Milsom Street. In her recent essay “What Jane Saw—in Henrietta Street,” Jocelyn Harris has explored Austen’s interest in satirical prints.

19In the Georgian era, traders, tradesmen, and tradeswomen were considered to be above unskilled workers on the social scale but below merchants and those engaged in the professions. See Barker 10.

IMAGES

Figure 1. François Alexandre Pierre de Garsault II. Staymaker’s Studio. Art du tailleur, contenant le tailleur d’habits d’hommes: les culottes de peau; le tailleur de corps de femmes & enfants; la couturiere; & la marchande de modes (1769), detail of Plate 13. Bunka Gakuen University Library.

Figure 2. Unknown American maker. Corset (c. 1770–1790). Quilted cotton, tan leather, baleen boning. Kent State University Museum, Silverman/Rodgers Collection, 1983.001.2481.

Figure 3. Unknown French maker. Woman’s Dress (Robe à la française) with Attached Stomacher and Matching Petticoat (c. 1770–1780). Bright green and white striped silk plain weave exported from China; silk looped trim; silk taffeta. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Purchased with the Whitman Sampler Fund, 1981, 1981-9-2a,b.

Figure 4. After John Collet. Tight Lacing, or Fashion before Ease (Bowles & Carver, 1777). Hand-colored etching. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 5. William Hitchcock. Tight Lacing, or, The Cobler’s Wife in the Fashion (1777). Hand-colored etching. Lewis Walpole Library, 777.11.04.01+.

Figure 6. William Humphrey. Tight Lacing (1777). Etching. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 7. After Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun. Queen Marie Antoinette (after 1783). Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Timken Collection, 1960.6.41.

Figure 8. Ruth Stephens. Corset (1785–1795). Linen, wood, leather. Daughters of the American Revolution Museum, Washington, DC, donated by Mrs. A. F. Bruchholz, 2505.

Figure 9. Daughters of the American Revolution Museum, Washington, DC, #2004.51. Photograph courtesy of Mackenzie Sholtz, from unreleased Fig Leaf Patterns (FLP 118).

Figure 10. Unknown English maker. Stays (1770–1790). Silk damask, lined with linen, reinforced with whalebone, hand-sewn. Given by Messrs. Harrods Ltd, T.909-1913. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Figure 11. Unknown English maker. Stays (1780s). Silk taffeta, lined with silk, ribbon. Given by G. J. Stewart. T.188-1961. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Figure 12. Pietro Antonio Novelli. The Attitudes of Lady Hamilton (c. 1791). Pen and brown ink on laid paper. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1988.14.1.

Figure 13. Unknown American of European maker. Evening Dress (1810–1812). Indian muslin. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Gift of Mrs. M. Dow Brine, 1924, 2009.300.2685.

Figure 14. Unknown maker. Stays (c. 1805). Hand-stitched cotton, with baleen boning. Connecticut Historical Society. Gift of Mrs. Katherine H. Annin, 1963.42.4.

Figure 15. Unknown English or French maker. Stays (c. 1790). Cotton with silk embroidery, boning, and lined with linen. T.237-1983. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Figure 16. Reproduction of Apron Front Dress with Long Sleeves (c. 1799). Daughters of the American Revolution Museum, Washington, DC. Pattern made from the original by Fig Leaf Patterns (FLP 103).

Figure 17. Unknown maker. Canezou. Private collection. Photograph courtesy of Mackenzie Sholtz.

Figure 18. Unknown maker. Jacket (1797–1802). Silk taffeta. Daughters of the American Revolution Museum, Washington, DC. Donated by Jan Whitlock, 2005.6.

Figure 19. Unknown maker. Corset owned by Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte, 1803–1806. Silk. Maryland Historical Society. Gift of Mrs. Charles J. Bonaparte, XS.5.209.

Figure 20. Trade card for Rudderforth, Stays and Corsets (c. 1785). Heal 112.27. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 21. Unknown American maker. Stays (c. 1800). Homespun tan linen, boning, deer skin. Sold at Augusta Auction on 16 Nov. 2016, New York City, Lot 3, 45.17103.91.3. https://augusta-auction.com/search-past-sales?view=lot&id=17103&auction_file_id=45.

Figure 22. Costume Parisien: Coeffure en Nattes, Corset á la Ninon. Journal of Ladies and Fashion (1810).

Figure 23. Unknown maker. Princess seam soft corset. Private collection. Photograph courtesy of Mackenzie Sholtz.

Figure 24. Unknown American maker, possibly from Ohio. Corset (1820–1830). Cotton, bone. Daughters of the American Revolution Museum, Washington, DC. Donated by Mrs. Arthur G. Houghton, 65.229.

Figure 25. After Charles Ansell (?). The Virgin Shape Warehouse (S.W. Fores, 1799). Hand-colored etching. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 26. James Gillray. Progress of the Toilet: Plate 1: The Stays; Plate 2: The Wig; Plate 3: Dress Completed (Hannah Humphrey, 1810). Etchings. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 27. Thomas Sanders after Tim Bobbin. Untitled. Human Passions Delineated, plate 19 (1773). Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, 1963.30.22613.

Figures 28 and 29. William Hogarth. Before and After (1736). Engraving. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Before_and_After_(Hogarth).

Figure 30. Simon Francis Ravenet after William Hogarth. Marriage a-la-Mode, Plate V (1745). Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Sarah Lazarus, 1891, 91.1.111.

Figure 31. The Stay-Maker Taking a Pleasing Circumference (Carington Bowles, 1784). Hand-colored mezzotint. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 32. Nicolas Dupin after Pierre-Thomas LeClerc. Tailleur Costumier Essayant un Cor à la Mode [Tailor Trying a Fashionable Body] (1778). “Galerie des Modes, 15e Cahier, 1ere Figure.” A Most Beguiling Accomplishment. 10 Nov. 2012. http://www.mimicofmodes.com/2012/11/galerie-des-modes-15e-cahier-1ere-figure.html.

Figure 33. Unknown French maker. Pierrot Jacket (ca. 1785). Silk, linen. Metropolitan Museum of Art 1998.253.1. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest, Isabel Shults Fund and Millia Davenport and Zipporah Fleisher Fund, 1998.